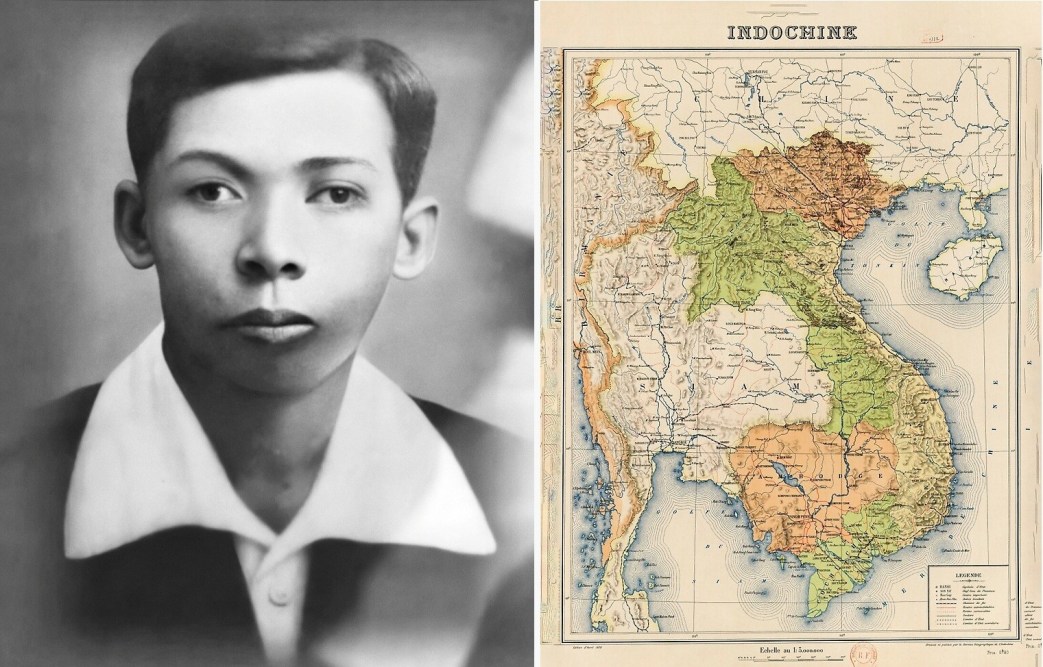

A speech during the Communist International’s extensive Sixth Congress discussion on the colonial revolution on France’s Indo-China colony, today’s Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. A founder and the first General Secretary of the Indochinese Communist Party, Trần Phú began political life as a young leader of the New Vietnam Revolutionary Party, was further trained in the revolutionary cauldron of China’s Guangzhou province before entering Moscow’s University of the East and acting as a Comintern delegate for Vietnamese Communists, though an official Party had yet to be formed. The speech below lays out the social and political conditions of the colony as well as touching on the conflicting notions of the ‘class vs. class’ or ‘national revolution’ character of the unfolding revolutions that underlay much of the discussion. Returning to Vietnam to help lead the newly formed C.P., Trần Phú was arrested by colonial police in Saigon on April 18, 1931 and died after months of torture on September 6, 1931 at 27 years old. (While I am not 100% sure the pseudonym ‘AN’ is for Trần Phú, I can not think of any other comrade it could be.)

‘Indo-China and the Revolutionary Movement in the Colonies’ by AN (Trần Phú) from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 8 No. 74. October 25, 1928.

Thirty-fifth Session. Afternoon. August 17, 1928.

Comrade AN (Indochina): There is a country which seems to be forgotten by the whole world, a country where cries of anger and rage, where the efforts of the people to liberate itself are absolutely stifled. This is the country about which I want to speak Indo-China.

It is a fact that Indo-China which has 20 million inhabitants, has been enslaved for 70 years; it is one of the first French colonies, and if this “French stronghold in the Pacific” were to separate itself from the mother country, the latter would be considerably weakened. It is also perfectly clear that by its geographical position Indo-China is coveted by Japanese imperialism and has therefore become a source of sanguinary conflicts in the Pacific.

Thus the Indo-Chinese problem is one of the most important problems for French imperialism. Hence, its efforts to suppress any attempt on the part of the Annamite people to throw off its yoke.

I do not want to enumerate here all the misdeeds committed by the colonists in regard to the natives. Everyone knows that imperialism, by conquering the colonies, brings with it murder, pillage, assassination, robbery, syphilis, alcohol and opium; everyone knows that the colonial sharks, in order to impose their domination, destroy all the customs and habits, the civilisation of the conquered people; everyone knows that to reduce a people to slavery one must keep it as ignorant as possible, one must give it “horizontal and not vertical instruction”, to quote the Governor-General Merlin. One must prevent it leaving its country to achieve “its civilisation” elsewhere, one must not allow it to go to the mother country to complete what the “civilising mission” has given it (the way to France is the way against France, said Cognac, Governor of Cochinchina), everyone knows all this. Neither do I want to enumerate here all the outbreaks and rebellions drowned in blood by which, since the establishment of the French rule, the Annamite people has vainly tried to get rid of imperialist oppression.

I will merely give to the comrades an exposé of the present economic and political situation in Indo-China so as to find practical means to help this people to liberate itself.

I said that Indo-China is of enormous importance to France. Certainly as a reservoir of rice (Cochinchina is, after Burma, the second rice-producing country in the Far East), of mineral raw material: coal, iron, copper, etc., and owing to its enormous fields for the cultivation of industrial crops (rubber) and its enormous numbers of men who provide cheap labour power and can serve as cannon-fodder in time of war, Indo-China has not its equal as a colony.

In 1927, the total trade amounted to 9,200 million francs, 4,200 million for import and 5,000 million for export. This is an increase of 5,000 million since 1925. In 1927, France exported to Indo-China 2,100 million francs worth of goods and imported 1,200 million. Japan imported from Indo-China between 1922 and 1925, 385,407,000 yens worth of commodities and its export amounted to 33,689,000 yens. This shows the importance of the Indo-Chinese market in the far East, especially for Japan.

Industrial capital invested in the private industry amounts to about 2000 million francs and it is estimated that, provided public works and public services were properly managed, one could raise every year the equivalent of the invested capital.

To give you an idea of the exploitation of Indo-China, let us quote a few figures: the nominal capital of the Bank of Indo-China, is 72 millions, of which 70,200,000 were set free. In 1919 the old 125 franc shares were set free at 475 francs. In 1925-26 net profits amounted to 36,000,000, that is to say 50% of the nominal capital. At this rate, the accumulated assets, the non-distributed profits of the Bank of Indo-China are estimated at 778 million! This is the result of 50 years of civilisation! The “Société Financière” of France which has a nominal capital of 50 million of which 26,602,000 were paid in on December 31, 1926, gained in 1926 24,385,000 francs, namely nearly 50% of its capital.

Moreover, France is not only exploiting Indo-China, it endeavours also to monopolise imports in this country.

Another significant fact is that the machinery imported in 1917 amounted to 5,480,000 francs whereas in 1924 it amounted to 64,885,000 francs. For cotton and wool in 1927 3,788,000 francs, in 1924 50,742,000. The consumption of coal in 1913 amounted to 199,400 tons whereas it amounted to 589,000 tons in 1924.

That increased exploitation is contemplated is shown by the extensive plans to penetrate into the virgin regions of Mocs in Annam, into Laos and Cambodia. French imperialism places great hopes on the completion of the Trans-Indo-China Railway which will facilitate the transport of labour power from Tonkin to Cochinchina. It also reckons on the construction of the railway from Pnom Penk to Battambang (the cost of which is estimated at 16,400,000 piastres), for the exploitation of this as yet untouched region.

The increased exploitation of the imperialists is accompanied by a development of the national industry (I mean the industry in the hands of the national bourgeoisie), especially since 1925. Textile factories, etc. have been established with native capital. Trade capital is also developing. There are many trading companies throughout Indo-China. The native bourgeoisie has a bank of its own with a capital of 250,000 piastres. We know very well that Imperialism will not tolerate this. Although it is not yet proceeding openly, we can see that it is beginning to interfere with the development of the national economy. For instance it supplies engineers, students graduated from French universities with capital to keep them away from the native capital. Thus we can say that in the industrial sphere the industrialisation of Indo-China has already begun, that side by side with industry in French and foreign hands there is an industry controlled by the Indo-Chinese bourgeoisie.

This is accompanied by a decline of home industries. Foundries, lacquer works, cabinet making, are disappearing rapidly owing to the competition of the big companies. Thus there is nothing left to the artisans than to abandon their trade and to seek employment in the factories.

In the agricultural sphere, the production of rice is in a state of stagnation. If we calculate the production in thousand tons we get the following picture:

1914—5497

1915—5470

1918—5407

1924–5677

Thus, in ten years, production increased by barely 200,000 tons. On the other hand big progress has been made in regard to industrial crops, especially with the cultivation of the hevoi (caoutchouc) of which there are at present 6,208,586 plants. In 1925 the export of rubber amounted to 8,700 tons and in 1926 to 8,798 tons.

Let us study now the social strata of Indo-China, the life and labour conditions of the workers and peasants. We are told that there is no proletariat in Indo-China. Comrades, allow me to disagree with this. Although we have not a numerous proletariat distributed throughout the country as in Europe, we have nevertheless a strongly concentrated proletariat in the big industrial centres. Although Indo-China’s economic development is uneven, there is concentration. I will give a few figures to add weight to my argument. There are 33,883 workers in the Tonkin mines, including 26,000 in the coal mines. The cotton company of Mann-Dinh employs 4,500 workers, the Franco-Annamite Textile Company 2,050 in the factory and 4,000 home workers. Women are also employed by this company (400 in the textile factory). Children 8 to 10 years old are also employed. Their pay is ridiculously small. Men earn 30 to 40 sous per day, women 20-25, and children 15 to 20. They are kept at work 13-14 hours.

This concentrated proletariat has already shown that it can be revolutionary by the movements which took place in 1925-1926-1927 when they demanded higher wages and a higher standard of living. During a strike of 2,500 workers in Namdinb the main demand was: a wage rise in accordance with the cost of living. They also give trouble to the colonial government. Thus 8000 arsenal workers went on strike refusing to repair the s.s. “Jules Michelet” which was to massacre the Chinese people. I reiterate, there is a proletariat in Indo-China, and this proletariat is strongly concentrated.

As to the peasantry, I must say at the outset that most of the land belongs to the big landlords. The remainder is in the hands of the middle peasantry which is very numerous. Landless peasants must take land on lease, giving up 60% of the harvest to the big landlords; they must make presents on New Years Day (two piastres per hectare of the leased land) they must also work free of charge on the birthday of the landowners and also during the dry season (drying up of fish ponds, gardening for the landowners, etc.); in a word peasants live under abominable conditions. Overburdened with taxes, crushed by the high land rent, forced to labour for the landowner, the poor peasants are compelled to remain slaves of the soil which gives them hardly enough to live upon. They are also subject to the usurious regime of the landlords; during the labour season when agricultural workers are deprived of all resources they give them loans either in kind or in commodities at an interest of 18-30%. This compels many peasants to abandon their land and to go to the cities where they work as coolies and rickshaws. In a word, leasehold conditions, the feudal system of the big landlords, ever-increasing taxes, are the cause of the growing destitution of the peasants who turn their backs on the land which cannot feed them and go to the industrial centres. In addition to all these hardships we witness also attempts at land expropriation on the part of imperialism. The result of all this is an ever-growing radicalisation of the peasant masses. This radicalisation finds vent in the resistance of the masses to expropriation which takes the form of rebellions which imperialism drowns in blood (rebellions in the village of Ninhanh Loi of Thung Thanh, etc. where all the houses of the natives were burned down). Thus the Indo-Chinese peasantry is of great importance to the future revolutionary movements.

Apart from the peasants and the urban proletariat we have a kind of proletariat which by its conditions of labour from 5 a.m. to 6 p.m. by its conditions of life and hygiene (63 deaths on an average per month on a rubber plantation) is even more destitute than the two former categories. They are the planters of rubber, most of them peasants whose land could not keep them or who were driven away from the land by floods, and were compelled to sell their labour power in these dangerous regions. These planters are terribly exploited by the settlers, who illtreat them mercilessly, kill and massacre them. This causes outbreaks which develop info armed rebellions which however lead only to the massacre of the insurgents. Thus the question of plantation workers is of considerable importance to us.

Let us now examine the political situation in Indo China. Big changes have taken place in Indo China since 1925. Although armed rebellions took place before, they did not assume a mass character. It is only since the arrest of the revolutionist Chan-Hoi-Chau on Chinese territory and his delivery to Indo China to be tried that an outbreak of rage and indignation swept over all the social strata of the country. But this was not only due to a nationalist feeling which took possession of the whole people against imperialism which arrested the man whom it reveres most, but also to the miserable conditions of life and the oppression which is weighing heavily on the masses. This sudden awakening would have developed in 1925-26 into a mass revolution to oust imperialism if the arrival of the Socialist Varenne, sent opportunely by the French government, had not awakened illusions among the Annamite élite. We must bear in mind that the Chinese revolution has a great influence on the Annamite masses. The saying is: China is the dawn of Indo-China.

Comrades, more competent than I have already spoken on the treacherous attitude of the Second International. With your permission I will deal only with “our governor-general”, “our viceroy”, our “Socialist” Varenne. It seems that this old fogy of the Socialist and Labour International was very popular, it seems that he displayed remarkable statesmanship to make the government send him to Indo China just at the moment when the masses were prepared to take up the fight for their liberty. There were magnificent demonstrations for his reception at Hanoi, several thousand Annamites met him carrying posters bearing the slogan: “Long Live the Socialist Varenne”. On his route old women knelt down to ask mercy for Chan-Hoi-Chan. He was received in Saigon by a delegation of 800 natives who had come from all the parts of the country to present a list of complaints and demand elementary reforms: freedom to hold meetings, freedom of the press, freedom of association, etc…All this came about spontaneously with a great deal of enthusiasm because much was excepted of the Socialist Varenne.

And the Socialist Varenne played his role, a role which he defined thus before his constituents of the seven mountain districts at the end of his farewell banquet:

“It (the government of the republic) was of opinion that the name alone of your representative would have in Indo China an appeasing and conciliating effect. I think that there are already sure signs that events vindicate the success of the government.”

Certainly Varenne’s “Socialist” label had created many illusions among the masses. To them Varenne, the “Socialist”, personified liberty and liberation itself. Alas, the traitor to Socialism, Varenne, did not wait long to show the masses that their hopes were in vain. He was already taking off his coat to exercise unprecedented repression against those who had dared place their hopes in him, the representative of the French working class, the liberator of martyred Indo China!

After all, what has Varenne done for the Annamites during his reign? Suspension of newspapers interdiction of pamphlets, sentences of imprisonment for years for writers and editors of anti-imperialist organs, expulsion and arrest of students on strike, arrest of employees and workers on strike. There were never so many strikes as during Varenne’s rule. He did his mission well. It consisted in being merciless with the malcontents.

What other benefits did the Socialist Varenne bestow on Indo-China? Decrees on the press, enormous subsidies for pro-French newspapers, increased taxes, increased police and army, construction of fortifications, of strategical railways to the Chinese frontier, a draconic decree against the working class. To this must he added the 7000 rifles which he allowed to go through to the Yunan province to exterminate the Chinese revolution. There are also the tens of thousands of hectares of land which he stole from the natives to give them to his friend Maillot. One must say, governor Varenne is a loyal lackey of French imperialism.

But the important thing is that since the Varenne regime we can expose the role of the national bourgeoisie, which includes the elite of the Indo Chinese returned from France, and of its Party, the Constitutional Party, whose leader is Bui-Guang-Chin. The latter showed himself in his true colours on his return from France. When he arrived the Annamites thought to have in him their banner bearer and they came in their tens of thousands to meet him. But machine guns were levelled at the crowd. If Bui-Guang-Chin had not deserted his post a collision would have taken place between the French troops stationed in the port and the Indo-Chinese masses. Since then the leader of the Constitutional Party preaches collaboration with imperialism. In an interview he said that the bourgeoisie and the Annamite elite have property and do not wish a rebellion to interfere with their interests. He also said that he is not anti-French, that he hates methods of violence, etc. No wonder that the Indo-Chinese masses have turned away from their bourgeoisie which is not concealing its counter-revolutionary character.

The policy of collaboration between the French capitalists and the national bourgeoisie is a very dangerous Entente for the masses. Varenne knew it. Therefore he granted certain reforms to the Annamite elite: accession to posts in perfect equality with the French, higher salaries for functionaries to render them loyal to the government. The recent terrible repressions are due to this policy of compromise and collaboration. The intention is to strengthen the civil servants cadre, to give authority to native lackeys to crush the masses; students returned from France are bribed by heaping on them honorary titles. It is intended to establish an Indo-Chinese hostel in the university settlement in Paris as a bribe to the native students. All this is done to repress the revolutionary masses which have already taken up a hostile attitude towards their bourgeoisie. They know that they must work out their own liberation. Unfortunately, they are not yet organised. Apart from the constitutional party we have also the Annamite party of Independence created in Paris by a Communist renegade, Ng-Tch-Truyen. This is a very dangerous party which creates illusions among the masses because it preaches Indo-Chinese independence by means of a peaceful evacuation.

There is at present in Indo-China a party which is in contact with the masses, i.e. the Young-Annam party, which, although weak and without a political platform, is at least a rallying point for revolutionary petty-bourgeois elements. Our task is a very difficult one. It is essential for us to have a revolutionary mass organisation if we are to take the lead in the revolutionary movement of Indo-China. The situation in Indo-China is by no means so peaceful as Varenne made believe after the expiration of his mandate. The masses are imbued with the will to liberate themselves. The peasant and planters rebellions, etc., are alarming symptoms for French imperialism. The recent military manoeuvres which took place around the villages have no other aim but to intimidate the population. Lately a search was made among the mountaineers for alleged stores of arms. This is a pure invention to engineer a conspiracy so as to have a pretext to use repressive measures against the revolutionaries.

Comrades, I would like to say a few words about the Indo-Chinese working class. It is mainly provided by Tonkin and Annam, where destitution and floods drive the peasants out of the country to seek employment in Cochinchina and elsewhere. The newspaper “Indo Chinese Argus” has made public how the colonial sharks carry on slave-trade by sending coolies to work in the Hebrides under perfectly appalling conditions. The recent labour code gives absolutely nothing to the workers. It is evident that we must turn our attention to the Indo-Chinese labour power as an export commodity.

As to the question of Chinese in Indo-China, they are mostly concentrated in Cholou where they own big rice-fields. They also own big works in Tonkin. They are well organised and have their own chambers of commerce. Side by side with the colonial government they are an instrument of oppression against the Annamite masses. Nevertheless, the Government knows that the sympathy of the Annamites for the Chinese Revolution is growing and that among the Chinese there are revolutionaries who can teach something to the Indo-Chinese natives. Therefore, it endeavours to sow discord between the Annamites and the Chinese (Haiphong incidents). We declare here that we will do our utmost to help the Chinese Revolution, we will tell the Annamite soldiers sent to China to fraternise with the Chinese revolutionists if French imperialism tells them to exterminate them.

I spoke already of the covetousness of Japan and of the role which Indo-China might play in a war in the Pacific. These assertions are borne out by the military and naval reinforcement of Indo-China, by the plan to construct works for the manufacture of commercial aeroplanes, which in wartime can be transformed into military aircraft.

In conclusion, I would like to draw attention to the fact that in this country which French imperialism represents as quiet and peaceful, but where nevertheless big demonstrations of tens of thousands of workers, peasants and poor intellectuals and peasant rebellions took place which are alarming the land expropriators, that in this country where the proletariat is growing, where the radicalisation of the masses makes headway, where the bourgeoisie plays its treacherous role quite openly, that in this country the revolutionary masses are still unorganised and therefore impotent.

The C.I. must seriously consider the question of the creation of an Indo-Chinese Communist Party. It must turn its attention to the question of the formation of trade unions for the workers and also of organisations for the peasants. The complete emancipation of the Indo-Chinese workers and peasants cannot be achieved in any other way.

In conclusion, I would like to say that we set our hopes on the proletariat of the whole world, especially on the workers of France and China and on the Third International. With their help we will be able to work out our liberation.

To the Social-Democrats we say that we do not need their policy of compromise. Enslaved people, oppressed workers, exploited labourers and peasants as we are, we want only one thing: to liberate ourselves from the yoke of imperialism, from the parasitical national bourgeoisie in order to enter into the concert of the socialist world, in order to seek refuge under the banner of the Communist International.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecor” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecor’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecor, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1928/v08n74-oct-25-1928-inprecor-op.pdf