The coal fields of Southern Illinois, the sight of so much labor history, again step into the larger story of our class with a rebellion against a corrupt and violent union leadership in an attempt to form a democratic, fighting union. The Progressive Miners of America was one of a number national and regional attempts to build miners’ unions outside of the John L. Lewis led United Mine Workers of America, which had been in crisis, particularly since 1927, with the conflict fracturing the largest union and strongest force of the U.S. working class. William Stoffels with the high drama of those days.

‘Revolt of the Illinois Miners’ by William Stoffels from Labor Age. Vol. 21 No. 9. September, 1932.

IN the referendum of July 16, as I pointed out in my article in the August LABOR AGE, the miners rejected the proposed 28 per cent reduction by a very large majority. Without wasting any time the District officials then announced that the miners’ vote had been unduly influenced by irresponsible agitators, and that the agreement slightly modified would be resubmitted to the membership to vote upon.

When the scale committee first acted upon this modified agreement their vote was tied, whereupon John L. Lewis and his Lieutenant Sneed took part in the balloting. The result was a majority of two for the reduction. The District and International officials then made an extensive campaign over the state to induce the miners to also ratify this agreement.

The reception the officials received from the miners was rather cold. In some camps the miners simply walked out of the hall, leaving bare walls for the fakers to talk to. In other towns the reception was pretty hot. At Johnston City the brave Walker had his wife along for protection. But the miners of that place decided that the age of chivalry is past. They threw stones at Walker’s automobile. Broken windshields and bent fenders were the only damage, however.

The emperor J.L. Lewis did not expose his valuable person to such dangers. He spoke nowhere unless furnished ample protection. At the Benton Chautauqua Lewis received a roaring applause from the 500 special deputies, the 50 highway police and some business men that surrounded the platform.

On August 16, after having made exhaustive preparations, the officials resubmitted the tentative agreement to referendum. It differed from the first only in the switching of paragraphs. There could have been no doubt in anyone’s mind that to resubmit the same proposition to the same people to vote upon within a period of 30 days, must inevitably bring the same results.

As the votes were counted in the District office, the first hundred tally sheets showed a majority of approximately 5,000 to reject the new scale. Then happened something unexpected to the membership–the remaining tally-sheets were stolen. The District office immediately notified the local unions that an emergency existed, and, as Walker said, “Realizing our responsibility to the miners, and their families, and under the firm belief that the agreement has been ratified, and seeing our duty to the general public, we have signed the agreement.” He concluded by saying, “You are hereby instructed to comply with its terms.”

In view of many similar precedents, the miners were, however, not inclined to take Walker’s gab for sober truth. Besides, if these tally-sheets have really been stolen, are there not duplicates in each local union that could be collected within 24 hours?

The result of the officials’ machination was that the 8,000 miners that had been working under the old scale pending settlement came out on strike solidly. Those that had been striking since April 1, for the biggest part continued on strike, but an appreciable number, constrained by necessity, followed the officials’ dictum.

Bedlam reigned. The officials and their hirelings, together with the coal companies and their tugs, were as busy as bees to break what they call a dual movement. The strikers on the other hand were active day and night trying to make the strike unanimous. Some mines were working here and there. The four large Peabody mines at Taylorville were working full force. Both sides knew well that if the strikers could not conquer Taylorville their cause was doomed to failure.

The Peabody Coal Company owns not only four large mines but also Sheriff Wienecke in Christian County. Being well aware that the strikers would attempt to shut down the Taylorville mines Wienieke, to prevent this, appointed 1800 special deputies. He issued proclamations, manifestoes, and what-not, threatening what he would do to anyone trying to interfere with the operation of the Taylorville mines. Every road entering Christian County was guarded by a score or more deputies. Every highway police of Illinois, it seemed, had been transferred to Christian County. Some of the guards near the mines could hardly wait the appearance of the strikers’ pickets. For pastime, they here and there took a shot at passing automobiles. Perhaps the most impressive thing were the six airplanes of the National Guard which, from morning till night, circled over the Peabody properties.

Lewis and Walker naturally were also doing their best to avert the picketing of Taylorville. The day before the strikers moved on Taylorville, Lewis, speaking of them in the press, became rather suggestive. He said: enough to think that the good, honest “Surely these men are not dumb people of Christian County will let a wild, lawless mob horde overrun their beautiful and lovely county.”

When the strikers had their preparations made to picket Taylorville, they sent a committee to inform the authorities of their intention. But things always seem to happen at the wrong time. Apparently an epidemic broke out among the politicians. Governor Emmerson was very ill. The Lieutenant Governor was taking his last gasps. Both the Secretary of State and Attorney-General were about to “kick off.” The Chief of the Highway police had tremendous pains–his wife was having a baby. The Commandant of the National Guard had mysteriously disappeared, probably kidnapped. Unfortunately this whole gang recovered promptly after the Committee left.

The pickets of each local union were meticulously instructed to leave fire-arms and firewater at home. These orders, although orders, although they seemed preposterous to many miners, were followed to the dot. To properly describe the Taylorville picket line of August 18th, would require a Victor Hugo. The miners came by the thousands from all directions.

Confronted by this host, Wienecke drew in his horns, the Taylorville miners themselves marched out with flying banners to give their brothers a fitting reception. The whole thing miraculously ended without anyone receiving as much as a scratch. The Taylorville miners are now out.

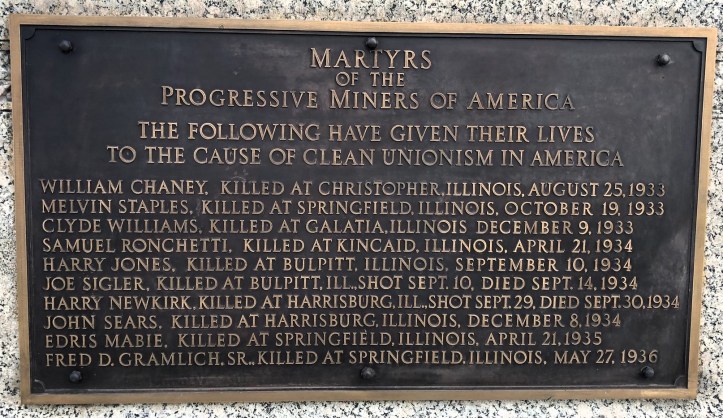

The Lewis-Walker-Operator gang, although defeated at Taylorville did not cease their efforts to put the Illinois mines in operation. They have made Southern Illinois a rendezvous of gun-men. They have instituted a reign of terror there and are receiving whole-hearted support from the sheriffs. Numerous casualties have resulted. The leaders of the strikers are shot on sight. Several have been killed.

Confronted by this dictatorship the strikers in Southern Illinois were helpless. The policy committee of the strikers decided to picket these mines with outside help. On August 24 order was again given, “no booze, no arms.” The picket lines that proceeded to Southern Illinois that day are unprecedented in the history of Labor. Below Belleville, where several of the lines converged, the procession was 45 miles long. It seems that every coal miner went, for in the coal camps only women and children were left to greet the crusaders. The program was to proceed to Dowell where a mass meeting would be held, to camp there for the night, and to enter Franklin County the next morning to picket the mines.

When the head of the procession arrived in the neighborhood of Dowell, the Highway police intentionally mis-directed it over a bridge into Franklin County. Machine guns were mounted on this bridge, ready for action. The beasts that manned these guns let about a hundred automobiles pass over, then they fired into the mass, kept up a steady fire, riddling with bullets everything within reach. The miners, unarmed, fled for their lives. Hundreds of bloodthirsty deputies armed with guns and clubs then, with undescribable fury, completed the carnage.

To the everlasting disgrace of Southern Illinois it must be recorded that even the hospitals refused admittance to men and women mortally wounded. There is indeed no animal so ferocious on this earth as the hypocritical, supposed-to-be-Christian rulers of that region.

The miners during that night withdrew from this inferno. To those retreating in the direction of Coulterville, the mayor of that town offered hospitality. About noon some 5,000 of these men held an open air meeting there.

Before the entire business of the Coulterville meeting was transacted the highway police arrived to harass the miners some more. Notwithstanding the fact that the miners had the permission of the Mayor to meet in Coulterville, these highway police, brandishing revolvers and machine guns chased the miners out. Men that were about to take their first bite in over 24 hours were compelled to drop everything and “beat it.”

The miners that met at Coulterville are only outwardly the same men who the day before, with flags and smiles, went to peacefully picket. Inwardly they are very much different. The dictators of Southern Illinois in 24 hours have accomplished more than a thousand labor agitators could in fifty years. They have beaten the miners on that day, but they have not conquered them. The victory, in fact, is on the side of the miners. They have regained the spirit that for years had been put to sleep by labor fakers. Their final victory is now assured. It is now extremely clear to these men that all the forces of government are determined that the miners must submit to a gang of cheating, unscrupulous labor racketeers, Lewis, Walker and Co. Rest assured, there are not enough cut-throats in the U.S.A. to stop the miners now. They will picket. But not any more will they act as targets for a gang of assassins.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v21n09-sep-1932-labor-age.pdf