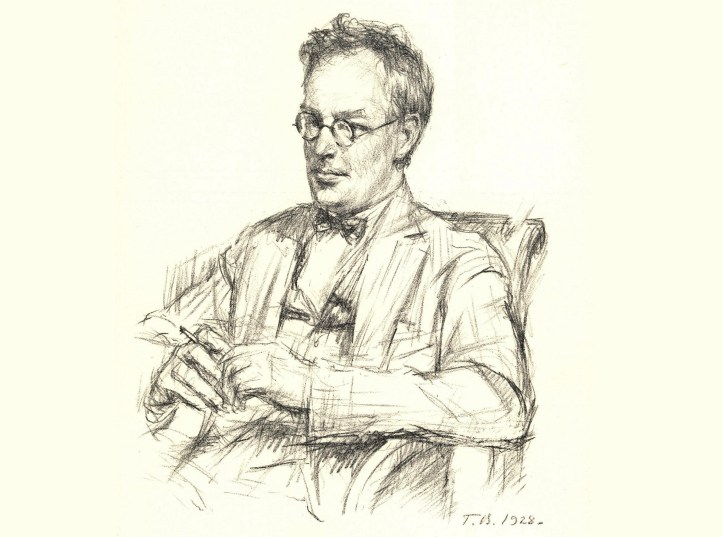

A magnificent essay from Victor Serge introducing his close friend Boris Pilnyak, among the greatest writers of his generation, and second only to Gorky for popular reading of his work in 20th century Russia. Serge, also a singularly gifted writer, and Pilnyak would be intimately intertwined for years after this essay; Pilnyak asserting whatever authority he had to save Serge’s life, until Pilnyak was arrested in October 1937, farcically accused of working at the behest of Japanese imperialism to kill Stalin and executed on April 21, 1938. First published in English in the Daily Workers’ Magazine. Wonderful.

‘Boris Pilniak, the Greatest of Russian Writers’ by Victor Serge from The Daily Worker. Vol. 1 No. 341. February 16, 1924.

PILNIAK is decidedly the most characteristic and the most celebrated of the Russian authors. His first work appeared in 1920 in the Moscow state edition. He writes. exclusively about the Revolution. He has written a novel, called, “The Bare Year,” as well as a couple of volumes of short stories: “Tales from Petrograd,” “Ivan and Maria,” which embrace the whole of the Revolution.

Pilniak’s manner seems strange at first. But it is in absolute harmony with the spirit of the time.’ He writes rather in the style of futurist painters. It would be utterly impossible to describe the Russian Revolution in the style of a Balzac describing tile sordid and monotonous life of a father Grandet, as well as with the utter indifference, the finish and perfection of style, with the absolute harmony of the whole of the detail—which we witness in Anatole France’s—“ The Gods Athirst.” It is only the writers of the time to come that will be able to describe the Revolution. We, as well as Pilniak, are incapable of doing so. The Revolution, which has done away with so many forms of the past, has alike cleared up many a literary prejudice of the past.

It is hopeless to look for a continuity of events in the work of this author. Intrigue (how pitiful this expression) does not exist. chief and secondary figures either, in his work. The movement of masses in which every single figure is a world for himself, representing in himself completion. Events rushing in and overpowering one, numerous human lives intermingling, each of which always represents in itself an occasion never to be repeated. The whole of them, in the end, of not much importance on the background of “Russia.” the snowdrift and Revolution, for the country, the snowdrift, and the masses, are the only things remaining and stable. The exterior aspect of Pilniak’s work corresponds to the contents of it. The pages often wear a somewhat strange aspect. One page carries the description of an old priest among his ikons, breaking under the burdens of his sins. Suddenly the narration breaks up and one hears the people in the street passing by, talking; a new interruption, and in comes, tearing along, a hungry, howling wolf with bared teeth. This constant change of description and pictures requires, of course, different aspects of the page. The reading of this book is, in a certain sense, rather bewildering. But the final impression is strong and powerful. Pilniak is under the influence of the masters of later years, such as Andrei Biely and Alexei Remizov, but he resembles them in manner only, and not in contents.

He has such a lot to show and to describe, and to bring out in his book, that every manner and form is oppressive to him. He lets life drift where it will. Classicism is of value, but in shapes long existing. In the “Bare Year” we find eight beautifully treated subjects: the little bourgeois, the dying aristocracy, the sectarians, the anarchists, the monastery, the train number 67, the peasants, the Bolsheviks. But the same stern unity reigns over all on account of a totality of the varying dynamics, as in some heroic symphony. In the course of the story “Ivan and Maria,” the shouting of a vainer, who has nothing whatever to do with the story is repeated, a black slave of international metallurgy, who quite inert and apathetic from his work seeks his couch for his nightly rest. But what a number of idyllic and psychologically fine novels would require just such a refrain in order to bring them back to the actualities of life!

The LEITMOTIV of the whole of Pilniak’s work is the snowdrift, the most Russian of things. Pilniak’s style is often extremely musical. The author leaves nothing unobserved, he is anxious to communicate and give back everything he sees, and everything that impresses him. In a word, dynamism, simultaneousness, absolute rhythmical realism, these are the dominant features of his literary form. We must not forget to mention his love of exact detail, of the minutest description of customs, of the sentence caught up in the street, all of which are simply given back without any particular commentary, exactly as some historian would note it.

Pilniak’s interest seems to concentrate itself chiefly on the mariners and customs of the Revolution, and this chiefly in the country and the provinces. The general play of action of his stories, is the small town (Riasan the Apple, or Ordynin Town) in “The Bare Year,” which he really does seem to thoroly know. What is the chief thing that he observes? The swamp of the past. In the small, provincial town the petty bourgeois leads a life not much better than that of a pig, between his counter, the well laid table, and the warm, sweaty, dirty bed under the saints’ pictures. He is brutal towards the weak, hard and of unbending will towards the oppressed— servants, women and children; self-satisfied, egotistical, ignorant, heir of a thousand similar years.

War took the young men out of the swamp of the small towns. “As Donat came back, he had learned nothing new, but the old was not forgotten, and be wanted to destroy the whole of it. He came in order to create.” He hated the old. The dread of it occasioned by the mighty shock of Revolution is one of the chief reasons of Revolution.

In this stagnating swamp of the times gone by the former rulers are abandoned to ruin on account of their weakened spirit, and their poor blood. In a word, it is an historical judgment that weighs over them. The princes Ordynin (whose fathers once founded the town of Ordynin) are at present syphilitic and are approaching their end. The old father is waiting for it, surrounded by his ikons, and practicing self-castigation. Egon is a drunkard, stealing and selling his sister’s last clothes in order to drink (this is the year 1919).

Chapter VII of the “Bare Year,” called, “without a title,” consists but of three words: “Russia, Revolution, and snow drift.” The beauty of Russia’s landscape blends with the drift of Revolution. One never knows how to discern them in Pilniak’s stories. I do not think that it is even necessary to do so. Pilniak compares old Asiatic Russia to the Russia of today, which he sees rising out of the drift, and we must admit that he sees it extraordinarily well, and that is his chief merit.

Listen to this conversation taking place in a rolling tram…“In a hundred years people will speak about the actual times as about the period of life when the human spirit rose to a glorious standard …well, but my shoes are very worn, I really would like to go on a trip abroad, to eat in some good restaurant and to drink a decent whisky.” These are the terms in which a young engineer is thoughtfully speaking in Pilniak’s book, quite like reality in new Russia; it is not the engineers that are life’s masters. This leads us to the Bolsheviks. Pilniak flatters the Revolution just as little as the revolutionaries. The gloomy pages as well as the nightmare ones are indeed not scarce in the course of has work. You see in his book peasant women paying with their own flesh and blood for a place in a filthy train full of bugs, a typhoid fever transport train, escaping out of the famine region. A little further a hysterical shooting down her lover. Peasants are described buying coffins for the whole of their family in advance, as they are quite sure not to be spared either by famine or typhoid fever. The book contains pages full of terror, one is, however, not quite sure whether the accents of it are real or pretended. Western people are yet not fully aware of the martyrdom that Russia underwent. Pilniak seems to be quite well informed, and writes it down accordingly with the blood of his heart. His constant aim is to be as close to exact truth as possible.

In the drift there is but one kind of people that remains upright, and these are the Bolsheviks. In the morning they used to meet in the convent (strange times indeed!).! Men not unlike leather, in leather jackets, almost all of them tall and manly looking, handsome and strong with hair curling out of their caps, pushed deep into their necks. Each of them had an excess of will in his tensed muscles, in the expression about the mouth and forehead, in the soft and decided movements of the lithe bodies, heaps of will and audacity. Here we are before the elite of the Russian people, one of the oldest in existence. And it really was a good thing that they used to wear leather, because thus the sweat lemonade psychology could not soften them. The whole of their bearing said “we know well what we are about, we have made up our minds.” Here is one of them described more particularly: “Archip Archipov used to spend’ his days in the Executive, in writing, and the evenings about town, in the factories, lectures, and meetings. He used to write knitting his brows, holding his pen almost like an axe. In his speech he used to pronounce the foreign words incorrectly. He was an early riser, and in the morning he crammed and crammed as much as he could; algebra, political economy, geography, Russian history, Karl Marx’s Capital, he had a German grammar, and a dictionary of Russianized foreign words by Gavkin.

Father Archip, on receiving the information of his having cancer, condemning him to awful sufferings and unavoidable death, goes to his son, and talks to him about it: “do you believe it to be a wise tilling’ to make an end of it?” he asks him. An impressive scene follows. “I believe I’d do it if in your place, father, but of course you must act as you think best.” “Live, my son, go on working, marry and bring up children.” Not a word more is wasted on this occasion, both remain decided and sure as to the next thing to be done; the one for going on living, the other to blow his brains out.

Everything in Pilniak’s works is tense and painful, except a lighter passage following this stark one. A couple appear in it. A Bolshevik couple, strong and simple, both of them, and of an extreme inner honesty. The man Archipov speaks to the girl called Natalia, whom he wants to have for his wife: “I am always in the factory, in the Executive, quite taken up by the revolution…as a young man I have had some love affairs, I have sinned with But it did not last. I have never been ill. We shall work together. We shall have handsome children. I want them to be sensible, well, you know, besides you are better educated than I am. But I won’t give up studying. We are young and healthy.” Archipov hung his head. She consents with no less simplicity. One might be inclined to think that these revolutionaries are afraid of, and trying to avoid the passionate impulses that burn in a couple who are about to mate…“Yes, children, that is the chief thing, but I am no longer a young girl. The man shrugs his shoulders. Chief thing is to be human.” Cleanliness, reason! “Love or no love,” she goes on speaking, “we will have an intimacy of our own and children, and then work, work, my love! There will be no lies between us, no suffering!” Archip turned silently back to his room. The word intimacy was not mentioned in Gavkin’s dictionary of the Russianized foreign words. Has the author, perhaps, been trying to idealize the Bolsheviks? It does not room. The word intimacy was not the will to establish a new form of life is their dominating trait.

Surely Boris Pilniak has seen other heroes than those during the revolution in Russia. But the Bolsheviks are the most deliberate ones, conquest is in them, simplicity, reason, conscience, will.

In the meantime the Russian anarchists are proclaiming a passionate philosophy of strength, “who are free under a black banner,” working in the fields of a confiscated prince’s estate, at the same time during which the Revolution was fighting on its whole front. They do not attempt to seize the leadership in Revolution, but they drift along, making use of it wherever they please. “Natalie had again a feeling as the Revolution carrying her off to some region of joy where, however, sorrow was always following every tempest of joy” …They work, work, love, dream and fight. And their adventures end, as has often been the case in the Ukraine. When the old emigree, Harry, asks for his share of money, which was seized in Ekaterinoslav, Youzik refuses to give it. Shots are fired in the night! Free people murder others no less free. They have murdered the handsome young woman because of money, they have murdered the woman who has tasted the violent joys of Revolution. And thus the black banner turns to be the shroud of the young dead thing. The Soviets send a troop of soldiers who occupy the forsaken commune. Somewhere Pilniak writes: “I remained in the free commune Peskis up to the day when the anarchists killed each other.”

I wonder whether I have succeeded in pointing out the strong realism of this new author, the strength of which is sometimes so overpowering that the immediate impression of things and particulars stifles the totality of the impression. This realist has a cult of energy and strength of man, beast and even nature. “The strongest among men are the revolutionaries and among beasts of prey.” Pilniak likes to introduce the life of wolves into the lives of men who are in a state of mutiny. “Thru wind and snowdrift in the sinking darkness, are the wolves trotting at the heels of each other a grey herd, males and females, the leaders ahead, and soon snow had covered their traces. (Ivan and Maria.)

Some of the stories of Pilniak from the years ’18 and ’19 are extremely remarkable on account., of their being radically different from his new things. The oldest ones are exactly in the grey dull tones of Tshechov’s worst period; the drama of the spleen in the utterly uninteresting life of a little bourgeois woman. The other ones, a shade better, describes the same sensations, as was usually done in the pre-revolutionary time. Life which had no issue on account of its utterly incurable mediocrity. Without the mighty uproar of revolution it is not at all unlikely that the author would have remained in the old current, and would not have added much to Russian literature. Boris Pilniak owes everything to the Russian Revolution, up to his style even; it was the revolution which gave him the originality of his talent, the insight in the development of things, the broad view with which he embraces boundless Russia, rich in suffering and struggle, the vision of surging strength, the whole of those things which were quite hidden to the authors of the old regime. That is one of the chief reasons why one is sorry to find in his writings only an intuitive perception and a primitive admiration of the revolution. What does this revolution want? A reader must be quite possessed and overcome by this idea on shutting this book.

What is the whole commotion about? Is the author capable of giving an answer to this? The lack of ideology, one might almost say, of convictions, deprives his work of a foundation. But it is precisely for this reason that it acquires in our eyes a quite particular value; because it is the best proof of his spontaneity, the frankness of his Statements. This work shows both in form and subject, how deeply the author, who himself admits to being neither a communist nor a revolutionary, is fully permeated by the spirit of revolution.

After having finished a commercial school, Pilniak left the provincial nest, in which he spent the heroic years of 1917-1921, but to supply his need in potatoes and flour. The whole of Pilniak’s interest is sacrificed to the social life interests. But our opinion is that he does not misunderstand the ideas, the influence of which, is but too well known to him. The totality of the ideas of a class of society that is struggling, carrying off victory and power, becomes an enormous factor in the renovating process of customs, this is the idea running thru all of his work. The new author is not yet in full possession of the whole of his strength. He is as yet not entirely clear, he is confused, hasty, bombastic, uneven, but despite all this, his work is today a beautiful grand song on the revolutionary energy of Soviet Russia.

(Translated from the French by H. Goering.)

The Saturday Supplement, later changed to a Sunday Supplement, of the Daily Worker was a place for longer articles with debate, international focus, literature, and documents presented. The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1924/v1n341-feb-16-sat-sup-1924-TDW.pdf