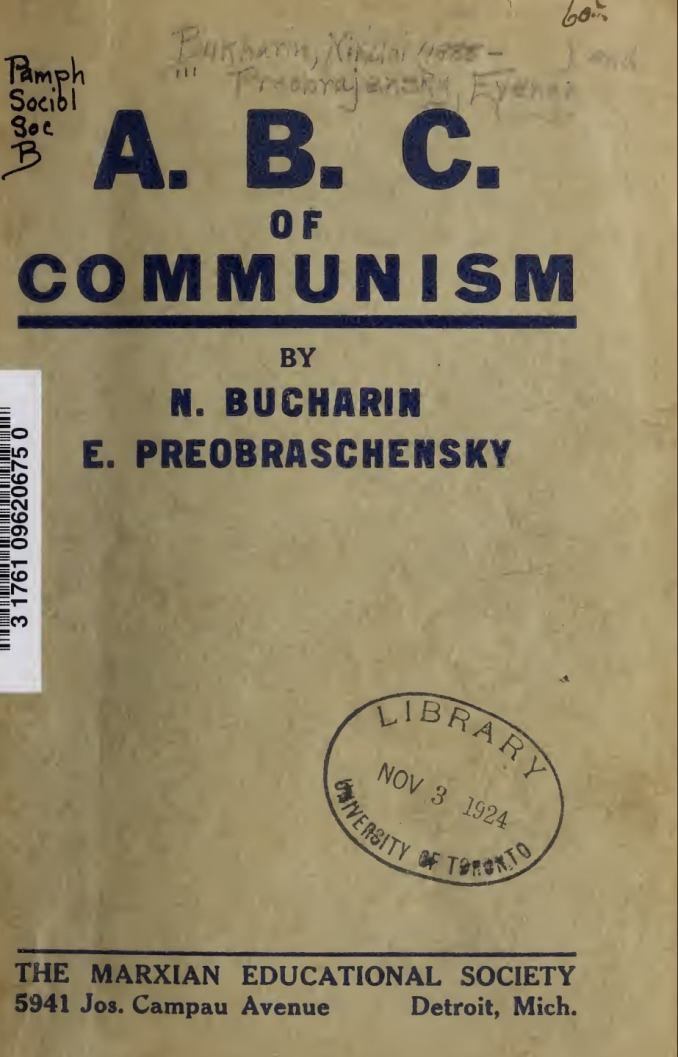

‘Imperialism,’ a chapter from among the most popular, expansive, and influential texts of the early Soviet experience internationally. Written by Bukharin and Preobrazhensky to explain the ideas and outlook of the Communists to a world audience of workers, this translation by Paul Lavin comes from the first U.S. publication of ‘The A.B.C. of Communism’ by Detroit’s Marxian Educational Society.

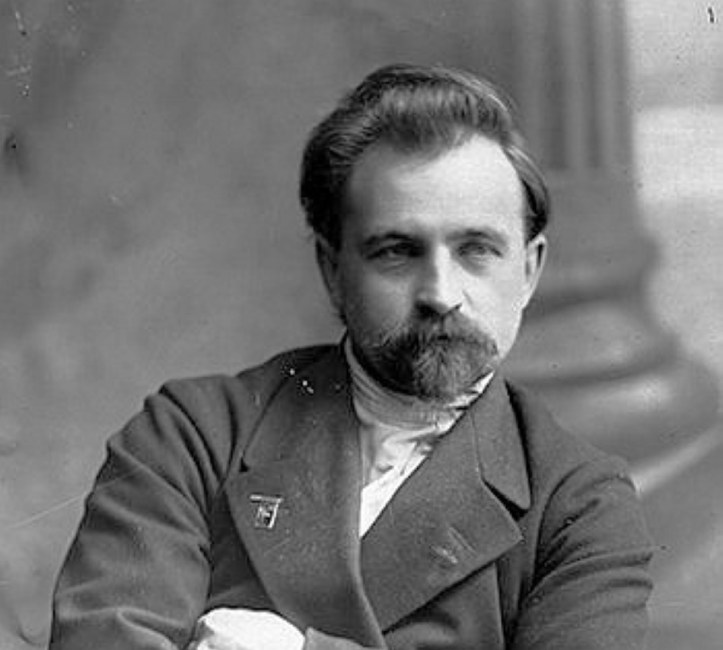

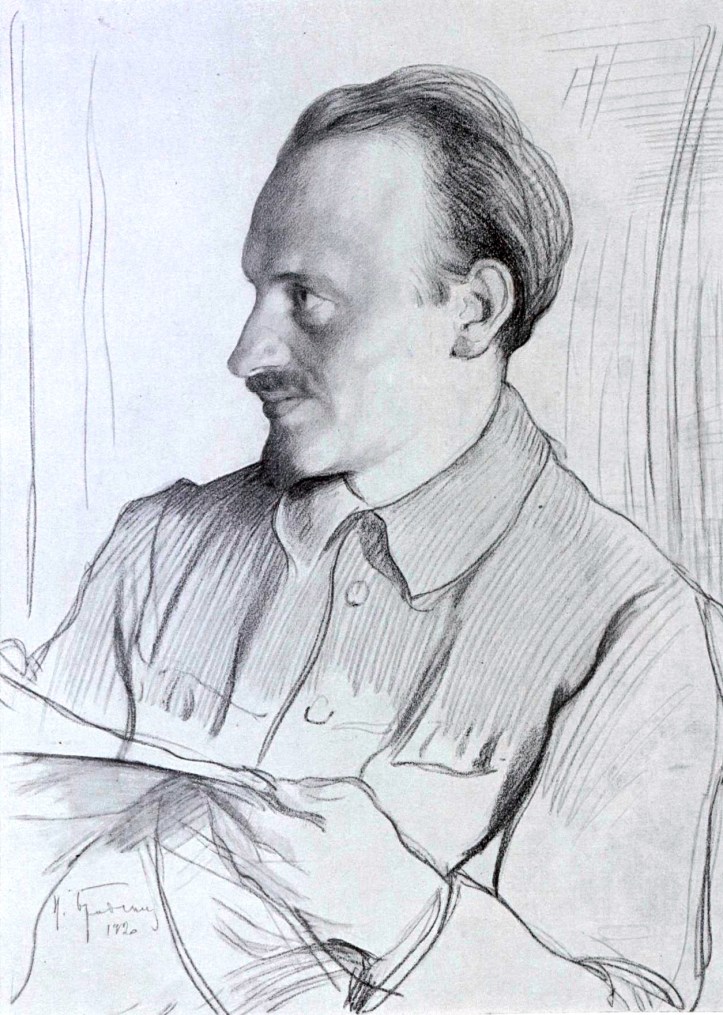

‘Imperialism’ by Nikola Bucharin and Yevgeni Preobrazhensky from The A.B.C. of Communism Translated by Patrick Lavin. Marxian Educational Society. Detroit, Michigan. 1921.

Finance capital removes the anarchy of capitalistic production to a certain extent in any given country. The individual capitalist, instead of fighting one another, unite in a State capitalist trust.

How does it stand, then, with one of the fundamental contradictions of Capitalism? We have said repeatedly that the destruction of Capitalism must come about because of the lack of organization in society, and because of the class struggle waged within it. But if one of these contradictions is done away with, is our prophecy of the downfall of Capitalism likely to be fulfilled?

The important thing for us to note is this: Anarchy of production and competition are not really set aside; or, to put it in another and better way, they are removed to another place where they appear in an aggravated form. Let us endeavor to explain this matter in detail.

The present form of Capitalism is World-Capitalism. All countries are interdependent; each one buys from every other. There is no place on earth which has not come under the rule of capital, and no country which, independently of the others, produces all it requires to satisfy its own wants.

A whole series of products can only be produced in certain places: oranges grow only in warm countries; iron ore can only be worked in those countries in whose soil it is met with; coffee, cocoa, and caoutchouc can only be grown in hot countries. Cotton is planted in the United States of America, India, Egypt, Turkestan, etc., and exported from these places to all parts of the world. Coal is exported by England, Germany, the United States, Czecho-Slovakia, and Russia. Italy has no coal deposits, and consequently is entirely dependent upon England or Germany for coal supplies. Wheat is exported all over the world from America, India, Russia and Roumania.

Moreover, some countries are more advanced than others. Therefore, the products of all the industries of the advanced nations are thrown on the markets of the backward countries. For example, hardware was sent to all parts of the world, chiefly from England, the United States and Germany, and chemical products principally from the last-named country.

In this way one country fs dependent upon another. How far this dependence can go is seen in the case of England, which imports from three-fourths to four-fifths of the grain, as well as half of the meat, it requires, but which must export the greater part of its industrial products.

Is competition on the world-market removed by finance capital? Does finance capital create a world-organization when it unites the capitalists in a given country? No. Anarchy in production and competition do indeed grow less intense in a given country, because the larger capitalists are busy organizing State capitalist trusts. But the struggle among these large trusts themselves proceeds all the more fiercely. One result of the concentration of capital can always be seen: the small men go to the wall. The number of competitors is reduced in this way, because only the larger ones remain. The latter now fight with more powerful weapons; instead of a struggle amongst individual manufacturers there is the strife of individual trusts. The number of the latter is obviously smaller than the number of manufacturers. Their fight is on that account all the more bitter and destructive. When, however, all the smaller capitalists of any country have been ousted and the others have organized themselves in a State capitalist trust, the number of competitors is not further decreased. The competitors now are the great capitalist Powers; and their struggle is waged at a fabulous cost and attended with enormous waste. The competition of the State capitalist trusts expresses itself in times of “peace” in the rivalry of armaments, and eventually leads to destructive wars.

Finance capital, then, destroys competition within individual States, but leads to widespread and embittered competition of these States against one another.

Why must competition amongst capitalist States lead at last to a policy of conquest and to war? Why cannot this competition be peaceful? When two manufacturers compete against each other they do not confront each other with knives in their hands. Each seeks to capture the market in a peaceful way. Why, then, has competition on the world-market assumed such a bitter and warlike form? We must here consider, in the first place, how the policy of the bourgeoisie had to be altered with the transition from the old form of Capitalism, in which free competition reigned, to the new form, in which finance capital began its domination.

We shall begin with the so-called tariff policy. In the international struggle, States (each protecting its own capitalists) found in tariff’s a weapon which long proved serviceable to the bourgeoisie. When, for example, the Russian textile manufacturers began to fear that their English and German competitors would introduce their wares into Russia, and thereby cause a fall in prices, the zealous Government immediately put a tariff on English and German goods. This, of course, made it difficult for foreign goods to find an entry into Russia. The manufacturers declared, however, that the tax was necessary for the protection of home industry. But when we examine the various countries closely we see that they are influenced by quite other considerations. It was no accident that the largest and most powerful nations, with America at their head, generally called for, and introduced, the highest tariffs. Had foreign competition really injured them then?

Let us suppose that the textile industry in a certain country is monopolized by a syndicate or trust. What then is the effect of the introduction of a duty? The heads of the syndicate in that country kill two birds with one stone: firstly, they free themselves from foreign competition; secondly, they can safely increase the price of their wares by the amount of the tax. Suppose that the tax for one metre of cloth is increased by one rouble. In this case the barons of the textile syndicate quietly add to the price of their own wares one rouble or ninety copecks. If there were no syndicate, competition amongst capitalists would immediately bring prices down again. But the syndicate can easily insist upon the increase. The foreign capitalist is kept at a distance by the tax; and competition at home is eliminated. The State in which the syndicate is situated receives a revenue from the tax, and the syndicate itself, through the increase in price, secures a higher profit. In consequence of this higher profit the lords of the syndicate are in a position to export their goods to other countries, and to sell them there at a loss with the object of driving their opponents out of the markets of these countries. The Russian syndicate of sugar manufacturers was able in this way to raise the price of sugar in Russia, and to sell it in England at a low price in order to over-reach its English competitors. It was a common saying in Russia that pigs were fed in England on Russian sugar. With the help of tariffs, therefore, the chiefs of the syndicates are able to plunder their own countrymen to their heart’s content, and to bring foreign markets under their sway.

Important consequences follow from this. It is clear that the profits of the rulers of the syndicate must increase as the number of people included within the area covered by the tax grows. When the area is a small one there is not much to be gained; but when it includes territories with large populations the gain is large, and anyone entering boldly upon the world market may hope for great success. The customs frontier, however, generally coincides with the frontier of the State. And how can the latter be extended? How can a piece of foreign territory be taken and incorporated in another customs district, or in another State? By war. By means of wars of conquest the denomination of the syndicates is secured. Every robber capitalist State wants “to extend its frontiers.” This promotes the interests of the rulers of the syndicates, of the owners of finance capital. “Extending the frontiers” is synonymous with waging war. In this way the tariff policy of the syndicates and trusts, which is bound up with their policy on the world-market, leads to the most violent conflicts. Other causes, however, contribute to this result.

We have seen that the development of production has as a consequence the uninterrupted accumulation of surplus value. In every advanced capitalist country, therefore, surplus capital grows incessantly. This yields a smaller profit than it would in a backward country. The greater the mass of surplus capital in a country is, the greater is the effort made to export it, and to invest it in other countries. This process is greatly facilitated by a tariff policy.

Frontier duties prevent the importation of goods. When, for example, Russian manufacturers imposed high duties upon German goods it became very difficult for German manufacturers to sell their wares in Russia. But when the sale of their goods was rendered difficult, the German capitalists found another way out: they began to export their capital to Russia. They built factories and works, and bought shares in Russian undertakings, or founded new ones, with their capital. Were they handicapped in this work by the tariffs? Emphatically no. On the contrary, not only were they not handicapped by the tariffs, but they were actually assisted by them. The tariffs served as inducements for the importation of capital. And that for the following reasons: If a German capitalist possessed a factory in Russia, and if he was also a member of a Russian syndicate, then the Russian tariffs helped him to pocket a larger profit. They were as useful to him in robbing the public as they were to his Russian colleagues.

Capital is exported from one country to another not only in order to establish and maintain new works there. Very often it is lent by one State to another at a certain rate of interest. (That is to say, the latter State increases its National Debt, or becomes a debtor to the former State.) In such circumstances the debtor State is generally obliged to raise all loans (especially those intended for military purposes) from the industrial magnates of the State which has lent the money. In this way enormous sums of money flow from one State to another, part of which is intended to be laid out in buildings and industrial enterprises, and part to be invested in the National Debt. Under the rule of finance capital, the export of capital reaches an undreamt-of height.

As an example of this, we shall give a few figures. These are already somewhat out-of-date, but they can teach us somethings. In the year 1902 France had 35 milliard francs invested in 26 States, of which sum approximately half was in the form of Government loans. The lion’s share of these loans (10 milliard francs) was in Russia. (By the way, the reason the French bourgeoisie are so enraged is because Soviet Russia has repudiated the Czarist debts and refused payment to the French usurers.) In 1905 the amount of exported capital reached the figure of 40 milliards. In 1911 England had about £1,600,000,000 invested in foreign countries. If the colonies are included, the sum will exceed £3,000,000,000. Germany had approximately 35 milliard marks invested in other countries before the war, and so on. In short, every capitalist State exported huge sums of capital to other lands in order to plunder foreign peoples.

The export of capital is attended with important consequences. The various powerful States begin to fight those countries to which they wish to export their capital. We must here draw attention to an important fact: when capitalists export their capital to a foreign country they do not risk the loss of goods, but of gigantic sums of money which are to be reckoned in millions, and even in milliards. It is self-evident, therefore, that the capitalists will have a strong desire to have completely at their mercy the small countries in which their capital is invested, and to compel their own armies to protect their capital. The exporting States determine to subjugate and exploit these countries. The different robber States attack the weaker nations, and it is clear that they will ultimately come into conflict with one another. And this actually does happen. The export of capital, therefore, leads to war.

With the coming of syndicates the struggle for the sale of goods was rendered infinitely keener. Towards the end of the nineteenth century there were hardly any free countries left to which either goods or capital could be exported. The prices of raw material rose, as did those of metals, wool, wood, coal and cotton. In the years immediately preceding the outbreak of the world-war a fierce hunt began for markets and a struggle for new sources of raw materials. The capitalists ransacked the whole world for new mines, ore deposits and markets, in order to export metal products, as well as textile goods and other wares, and to plunder a new “fresh” public. In former days many firms competed “peacefully” with one another, and got on very well together. With the domination of banks and trusts the situation has altered. Suppose, for example, that a new deposit of copper ore has been discovered. This gets into the clutches of a bank or a trust, which immediately establishes a monopoly over it. There is nothing left for the capitalists of other countries to do but grin and bear it. The same thing happens not only with the sources of raw material, but also with markets. Suppose that foreign capital has penetrated to a distant colony. The sale of goods is here organized on a large scale. Some large firm generally takes the business in hand, establishes a branch, and endeavors, by means of pressure on the authorities of the district by a thousand and one devices, to get the monopoly of the whole trade in its hands, and thereby keep its competitors at a distance. It is obvious that the operations of capitalists must be conducted on a large scale. We are no longer living in the “good old times,” but in the era of the struggle of the monopolistic robbers for the world market.

Therefore, with the growth of finance capital the struggle for markets and raw materials grows more intense and leads to the most violent collisions.

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century the great robber States seized upon the territories of many small nations. From 1876 to 1914 the so-called “Great Powers” annexed about 25 million square kilometres. They plundered foreign lands whose area is more than double that of the whole of the continent of Europe. The whole world was divided amongst the large robbers. All countries turned their colonies into tributaries, and made their inhabitants slaves.

Here are a few examples. From the year 1870 England acquired the following territories: in Asia—Beluchistan, Burmah, Cyprus, North Borneo, the district opposite Hong Kong increased its hold upon the Straits Settlements, and settled in the peninsula of Sinai; in Australasia—a series of islands, the eastern part of New Guinea, the greater part of the Solomon Islands, the Tonga Islands, etc.; in Africa—Egypt, the Soudan, with Uganda, East Africa, “British” Somaliland, Zanzibar, Pemba. She conquered the two Boer Republics, Rhodesia, “British Central Africa,” and occupied Nigeria, etc., etc.

Since the year 1870 France subjugated Annam, conquered Tongking, annexed Laos, Tunis, Madagascar, wide stretches of the Sahara, of Soudan and Guinea, acquired territory on the Ivory Coast, Somaliland, etc. The French colonies at the beginning of the twentieth century had a greater area than France itself (more than twenty times greater). In the case of England the colonies were a hundred times greater than the motherland.

Germany took a hand in the robber business in 1884, and in the short time since succeeded in acquiring similar large areas.

Czarist Russia likewise entered upon a robber policy, latterly principally in Asia. This led to conflict with Japan, which wanted to plunder Asia from the other side. The United States first obtained possession of numerous islands in the vicinity of America, then went further afield and established itself on the mainland. Its policy of conquest is particularly highly developed in Mexico.

The area of six of the Great Powers in the year 1914 was 16 million square kilometres, while their colonies comprised 81 million kilometres.

Obviously these robber campaigns affected first of all the small, defenceless and weak countries. These were despoiled first. Just as in the struggle between manufacturers and small artisans, the former destroyed the latter, so in this case the large States—trusts, the powerful, rapacious and organized capitalists—defeated and subjugated the small ones. In this way the centralization of capital in the world economy was accomplished. The small States went under, the great robber States grew richer, and increased in extent and in power.

But when the Great Powers had plundered the whole world the fight amongst themselves grew keener. The struggle for a re-division of the world had to begin; a fight for life or death had to take place amongst the remaining powerful robber States.

The policy of conquest pursued by finance capital in the struggle for markets, raw materials, and areas for the investment of capital is called Imperialism. Imperialism springs from finance capital. Just as a tiger cannot subsist on a vegetable diet, so finance capital could pursue, and can pursue, no other policy than that of conquest, rapine, violence and war. Each one of the State trusts ruled by finance capital actually wishes to conquer the whole world and found a world-kingdom in which a handful of capitalists belonging to the victorious nation alone will rule. The British Imperialists, for example, dreamt of a “Greater Britain” which should dominate the whole world, and in which the British bosses of the syndicates should have under their thumb negroes and Russians, Germans and Chinese, Indians and Armenians—in a word, hundreds of different kinds of black, yellow, white and red slaves. England is even now almost such a Power. With the supply of food appetite grows. The same is true of other Imperialisms. The Russian Imperialists dreamt of a “Greater Russia,” the German Imperialists of a “Greater Germany,” etc.

It is clear that in this way the domination of finance capital must hurl the whole of humanity into a bloody abyss of war—war in the interests of bankers and members of syndicates ; war, not for the defence of their own country, but for the plundering of foreign countries; war to put the world at the mercy of the finance capital of the victorious nation. Such a war was the great world-war of 1914-1919.

The Marxian Educational Society (appears) to have been a pro-Comintern group centered in Detroit that emerged from the forces of the Proletarian Party which dominated the post-World War One (and earlier) Left Wing in the city. They were responsible for publishing several of the classic works of the early Soviet experience and seem (?) to have joined the Workers (Communist) Party at its founding convention in December, 1921.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/abcofcommunis00bukh/abcofcommunis00bukh.pdf