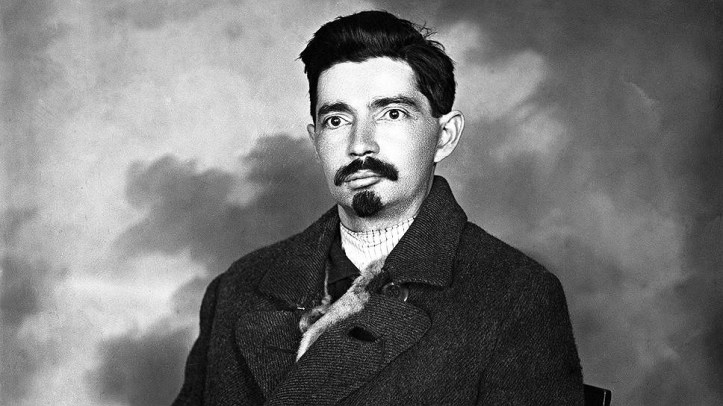

A fascinating, honest, and valuable report from the last months of the era of ‘War Communism’ on the extraordinary efforts in the most difficult of circumstances–the midst of invasion, civil war, and revolutionary dislocation–to restore industry and boost-production in order to defend Soviet power. While the Soviets emerged victoriously, ‘War Communism’ failed to feed its people or develop the still predominate peasant and agricultural economy. Already under discussion when this was written, the New Economic Policy abandoning War Communism in an effort to stimulate agricultural production and exchange would be instituted. By the Revolution, Larin–a Menshevik at first–had a long, rich, and difficult revolutionary career, arrest, prison, internal and external exile. One of the leading Mensheviks to align with the Bolsheviks in 1917, Larin was an original member of the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy and would spend much of his Soviet career in that field. He also did not fit into any of the blocks emerging in the factional disputes of the 1920s, leaving him increasingly isolated at the decade’s end. From a Crimean Jewish background, Larin took an interest in Jewish affairs, headed the Society for Settling Toiling Jews on the Land and advocated for Jewish agricultural communes in the Crimea and was sharply opposed to the Birobidzhan creating an autonomous Jewish region and removing Jews far from their traditional communities. He would perish of natural causes in 1932.

‘Workers’ Government Increases Production’ by Yuri Larin from Truth (Duluth). Vol. 5 No. 2. January 19, 1921.

Despite Three Years of Bloody Struggle, Proletarian Regime Emerges With Increased Strength; To Revise Monetary System.

The Revolution of the Russian Proletariat is no longer a newcomer in old Europe. It has become a constant factor in the life of the world, a factor whose influence is growing stronger and is more than ever in a position to shake to their foundations the mainstays of bourgeois rule. Comparing the end of the first year of our revolution with the end of the second or of the third, we find that the Soviet State founded in November 1918 by the Russian proletariat is the only rapidly growing power among all the states of the old world. In the autumn of 1918 Soviet Russia was enclosed within the limits of the Moscow territory, with 20,000 versts of railways and 60,000,000 people. In the autumn of 1919 it was strengthened by the re-conquest of the Ural, of the trans-Volga districts, and of the Ukraine. And now, in the autumn of 1920, Soviet Russia embraces almost the whole of the Caucasus, Siberia, Turkestan, and White Russia. The young Soviet Government is now in fact one of the powers that determine the course of world politics. The Red flag of the Soviet Republic waves over one tenth of the globe. This rapid increase of the weight of the Soviet Republic in the scales of the world, as compared with the old bourgeois and landlord-ridden states, serves as a symbol of the historical rise of the proletariat and of the imminent fall of the bourgeoisie.

Bourgeois Europe has for a long time been consoling itself and is consoling itself even now, with the thought that the downfall, of Soviet Russia is inevitable in spite of its accession of territorial strength and the consequent increase of material resources. Capitalist Public opinion considers the downfall of Soviet Russia as inevitable because, according to it, power in the hands of the workers must reduce itself to unwillingness to work and incapacity to organise work; in short, must lead to such a state that the country will be obliged to live upon old and rapidly depleting stocks of supplies until the inevitable collapse amidst general starvation–embitterment, pogroms, barbarism and mutual hatred. The Soviet Government may stand the military and political test, but it will inevitably perish on the economic field, that is the capitalist verdict. The rule of capital would then be re-established, the landlords’ whip would again play havoc with the peasants’ back, and the bodies of the workers would dangle from the lamp-post.

The problems of labour, the problems of organising the reproduction of all that the country consumes and must consume, are indeed fundamental, and the old stocks would not take us far. In this the bourgeoisie is perfectly right. If the victory of the proletariat is equivalent to the victory of indolence, of technical decline, of economic disorganization, then good-bye to Soviet economy. A temporary fall in production due to some external cause that may be removed, is not terrible. If however, organic vice exists in the very heart of the system, then no old stocks, however large, will be of any avail to save the country; and in Russia such old stocks have been comparatively small. It is therefore necessary to determine whether the fall in production is due to the very nature of the established system or is the outcome of some removable external cause. It is also necessary to ascertain the pace at which the disappearance of such a cause is progressing.

The first fundamental pre-requisite, the general volume of productive labour, has undoubtedly declined in Russia as compared with the pre-war period, up to 1915. Equally, there has been a decline in the output. Taking the output of our entire industry, we find that in 1919-1920 the average output of every worker per annum has not been more than 45 per cent of his output before the war. (We have taken our figures from the works of comrades Strumilin, Lossitzky, and Falkner prepared by them for the Commission of Comrade V. Groman which was set up at the instance of the Council of Defence and whose labours were concluded in October 1920. This work was undertaken with the object of determining the damage inflicted upon Russin by the imperialist blockade and by the support given by the Entente to the counter-revolutionary revolts and wars.). This, however, has been the result of two-kinds of influences. During the four years preceding the revolution 1913-1916, the factories and works never stopped for lack of raw material or fuel. In 1919-1920 however, there were on the average 53 lost working days per worker per annum due to lack of such raw material and fuel (metal ore, oil, coal, cotton, wool hides etc.) which were either entirely, or to a large extent, centered in the Southern and Eastern outlying borders of the former Russian Empire, and for three years were cut off from Soviet Russia by the counterrevolution. Before the war there was on an average loss of seven and a half days per worker in every year, whereas in 1920 this average reached 19 days, an increase which must be ascribed wholly to the war, to the counter-revolution and to the blockade which have created in Russia a famine in medicines, fuel, and provisions. It is really surprising that the number of cases of disease was not more than two and a half times the normal in spite of the terrible winter of 1919-1920 when in the large industrial centres there was almost no fuel and no possibility of procuring medicine and the health of the workers was undermined by insufficient feeding.

Under normal pre-war conditions the loss of time due to reasons, other than those indicated above, amounted to 16% working days per annum per worker, whereas in 1920 it increased to 35. The main cause of such loss of time was the departure of the workers into the country and to the “free markets” in search of food to be obtained in exchange for household utensils etc. While this loss is to be ascribed to the defective State machinery of supply, it is nevertheless compensated for by other measures taken by the government of the workers in the early days of its existence. The very decree which shortened the working day to eight hours (instead of the average 9.7 hours which, obtained in all the factories and works in 1913 the last year of peace) at the same time reduced the number of holidays (the holidays in honour of the family of the Tzar, as well as a number of religious holidays were abolished). In consequence of this, the normal number of working days in the year was raised by the Soviet Government to three hundred, as against the 264 obtaining in 1913. (It is to be noted that the number of lost days for reasons other than illness is, as we say, 35 which is just the number by which the normal number of working days was increased). Apart from this, the proletariat, the free triumphant class, has shrunk neither from lengthening the labour day nor from introducing work during holidays at the time when the struggle with the counter-revolution demanded additional effort. The average length of the working day in 1918 was eight hours; at the end of 1919 it was already 8.3 hours; and in the first quarter of 1920 it reached even 8.6 hours. The number of holidays on which work was being done exceeded, in 1920, by eleven days the number of days allowed by the law for annual holidays. The general number of hours during which the average worker has been employed during the past year represents in consequence of all the changes indicated above, 70 per cent of the number worked in 1913. This approximately corresponds to the loss of time due to the stoppage of factories and works on account of lack of raw material and fuel, and to loss of time on account of illness (particularly chronic were the typhus epidemics). Thus, the assertions of the hirelings of the European bourgeoisie, that the shrinkage in the volume of work in Russia is due to laziness on the part of the workers consequent upon their seizure of power, standing glaring contradiction to the experience of the last three years which on the contrary shows that the volume of work is gradually increasing.

In Russia as well as in the rest of Europe the productivity of the average worker has declined under the influence of the war. The worker works not only less hours in the year, but he produces less in each hour that he works. In 1919 the average output per hour represented only two thirds of the same output in peace time. In this respect two causes were decisive: first, on account of the military mobilisations the personel of the workers was changed, and second in consequence of the ring formed around Russia by the counter-revolutionaries, cutting off the industrial centres from the coal producing regions, the economic organisation of industry was destroyed.

By the autumn of 1918 Soviet Russia had a comparatively small army; but, in the last three months of 1918, in the first three of 1919) and in the following three months of the same year there were mobilised on an average eight hundred thousand men every three months in European Soviet Russia (exclusive of the Ukraine Caucasus and the Don). In the last three months of 1919, when we began to be victorious over the counter-revolution headed by Denikin the mobilisations were reduced to five hundred thousand men; and, in the first three months of 1929, when our victories over the Eastern counter-revolution headed by Kolchak made themselves felt, the mobilization dropped to three hundred fifty thousand. These figures prove better than could any diplomatic note that Soviet Russia was sincerely adverse to war with Poland. The attacks by Poland on Russia began on the 26th of April. Previously, Soviet Russia had been for the space of six months availing herself of the victories over Kolchak and Denikin, to reduce, month by month mobilisations so as to relieve, the heavy unproductive burden imposed upon the population by the necessity of beating off on all sides the attacks of the counter-revolution and of the Entente standing behind it.

On the whole, the number of people mobilised in Great Russia (including therein the Urals and the Volga) reached 40 per cent of all men between the ages of 20 and 39. Therefore, the places of many! workers had to be filled by women by elderly people and generally by untrained people; in consequence, the quality of work was reduced. The main cause, however, of the fall in the quality and quantity of labour was the famine created by the Entente and their Russian hirelings. At the end of the first year of the Revolution–the imperialist capitalism of the European countries, with the help of the Czekho-Slovaks and several Cossak generals, cut off the Russian industrial and forest centres with its 70 millions of people from the corn producing territories; and, if in 1918, European Russia had had such a poor harvest as the present one of 1920, it would have entailed the death of many millions) of people and all State organisation would have perished. The mere fact that in spite of the lean harvest of 1920 the State rations are being issued to the workers of Moscow more accurately and more lavishly than was done in 1918 when the harvest was bounteous, bears testimony to growth of organisation in Soviet Russia.

Still the feeding of the worker, even taking into account the food begot on the “free market” (that is by purchasing from the peasants or from speculators such purchases representing half of the food consumed by the worker) is considerably worse as compared with that of peace time. During the nine years preceding the revolution, 1908-1916, the average daily standard for an adult working man in Russia was 3,280 calories (reducing the food according to its nourishment into calories). However, at the beginning of 1919, according to investigations, the average was not more than 2,680 calories. At the beginning of 1920 similar investigations showed a somewhat bigger figure, viz. 2,980 calories, representing an improvement for the year of 10 per cent, but still 25 per cent below that of peace time. We can take 2,830 as these for the past two years (the data as to the quality and quantity of labour, the length of the working day and norms of output referring equally to these two years). Deducting 2000 calories, which are necessary for every adult person to maintain life without doing any work, we find that previous to the revolution, 1,820 calories were needed to enable the worker to work, whereas not more than 830 calories; that is, about 46 per cent, have been available during the past two years. It is interesting to know that the average annual output of each worker presents the same picture. His work expressed in hours being only 70 per cent of that of peace time and the output, of every hour being only two thirds of the former output it is plain that the annual output will be just 46 per cent of the former annual output. Consequently, allowing for the deterioration and non-repair of machinery, there should have been an even greater shrinkage, but this is evidently offset by the present productivity of labour, the latter now obviously being even higher than it was under the more favorable conditions of peace time. In other words the Soviet organ, the Government of the workers, in spite of all defects of detail, is in a better position to deal with the historical situation than was capitalism with the position which existed in Russia at that time. Having overthrown the masterclass, the workers stand a greater strain and try their best to produce more for their own needs than they were doing under capitalism. Therefore leaving out all other considerations concerning the country as a whole for the regeneration of agriculture and of industry, the Soviet organ is more advantageous than the reestablishment of the power of the capitalist and the landlords.

It would, however, be a mistake to assume that Soviet Russia has already reached an output which represents 45 per cent of the normal. We must take into consideration the decrease in territory. The Gromen mission mentioned above has calculated the shrinkage of production which would have set in even apart from the decline in the productivity of labour etc. The annual pre-war production expressed in gold roubles represented four and a half milliard roubles of agricultural products and two milliards of manufactured goods. In consequence of the reduction in size of Russia, taking into account the former productivity of labour etc., the agricultural output should have been 3.3 milliard roubles and that of manufactured goods one milliard. Now the actual Soviet output for the year, according to the calculations made by Gromen’s committee, has amounted to about 420 million roubles whilst agriculture amounted to two and a half milliards, (the figures are in gold roubles). Thus, although the annual average output of the industrial worker amounts to 45 per cent of the normal, Soviet Russia could not muster in 1919-1920 more than 20 per cent of the normal annual output of manufactured goods. This is the lowest limit of the shrinkage in the production reached in 1919-1920 on account of Russian being torn into isolated parts by the military attacks of the imperialist powers and the counterrevolutionary mutineers.

The reunion in the latter half of 1920 of the main outlying provinces with the centre has radically altered the situation. On the first of January 1920 there were in European Russia 350,000 poods of cotton. Now, on the 15th of October 1920, there are 3,050,000 poods besides that under way from Turkestan, whilst in Turkestan itself there are even larger supplies. From the middle of 1919 to the middle of 1920, European Russia consumed not more than 20 million poods of oil, all that there was to consume. Now we have in European Russia stocks amounting to 150 million poods of oil, brought during the summer from the Caucasus for the coming year, and there are great supplies left in the Caucasus.

The Donetz basin, the chief Russian metallurgical centre has been, for almost two years, in the hands of the reactionary Cossacks and Tzarist generals and Russia had therefore to live upon the exhausted stocks of old cast iron and scrap iron. Now, in the second half of 1920, we have been able to restore to order and re-open the coal mines which were closed during almost the whole time they were isolated from us, we have raised the output 15 or 20 per cent. the furnaces are beginning to blaze in the South after the long interval and the smelteries are re-opened, whilst in the North, in the Moscow region, the textile works which have been idle so long are again in operation. In short there is every indication that the coming year 1921 will see a great increase in production, considerably above the 20 per cent of the normal with which we had to be satisfied until now. Of course the result of this increase will be felt much later in the field of consumption, when such results will have had time to enter the channels of consumption, personal as well as industrial.

The past years were not only years of fighting for the life of the country and for the realisation of the possibilities of control over the country’s industries according to plan, by bringing the centres of raw material and fuel in close union with the industrial centres–they were more than that. They saw the concentration in a few hands of the management of all the technical resources of the country, and their regulated distribution; that is to say, during these years the technical foundation was created for a more powerful development of production in the future than ever was possible before the war. In this respect first place must be given to the laying of 6,000 kilometres of new railroad, which was done in the course of these three years; this means an increase of 10per cent in our network of railways built up in the course of 75 years by the previous regime upon the present territory of Soviet Russia. This gigantic work was made possible largely owing to the presence of special strategic reserve lines now no longer necessary, the rails of which have been used in laying the new railroads. A whole number of feeding lines were built in forest lands making possible their exploitation. (By the way, already in 1920, the felling of wood exceeded twice that done in Russia in peace time.)

Such a re-distribution of the technical resources of the country with a more rational and efficient utilization of the same, centered in one soviet authority, could not be achieved by capitalism split up in thousands of isolated units competing with one another even in the large and medium size industries. This re-distribution has served as a powerful weapon in the hands of the Soviet Government in order to reduce the harmful consequences of the long isolation of Russia, always hitherto dependent for new technical installation on purchases from abroad. The blockade being in force, many original methods were adopted for the construction of a new electric station at Shatourka, in the province of Moscow, boilers removed from submarines were used. There are plenty of such boilers to construct a number of such stations. It should be pointed out that Soviet Russia, in contra-distinction to Tzarist Russia, pays great attention to electricity. The writer of these lines has recently visited the province of Viadimir and found that 59 small electric stations were built in the course of the last few years in the villages. Each of these stations supply energy to a couple of villages, to the local mill, to repairing shops etc. There were also electric stations at 8 small towns in the province. Before the October Revolution the only station in the Province of Vladimir was in the town of Vladimir itself.

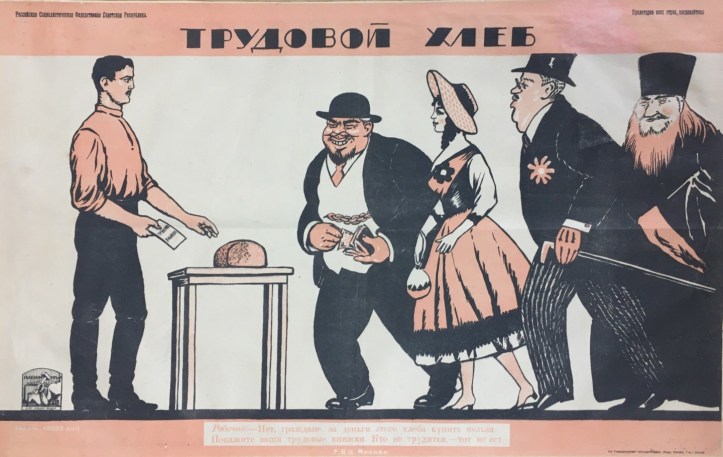

The gradual development of the economic organisation of Soviet Russia made it possible for the Soviet Government to deal with the question which is attracting the attention of all the governments of Europe, namely that of the monetary system, tackling it in, a way that no capitalist government in the world could do. What the Soviet Government is doing is gradually to abolish money itself. So far Soviet Russia has retained all the methods of using paper currency obtaining in capitalists’ countries, involving a process, well known since the Great French Revolution of the 18th century of ceaseless increase in the printing of new paper money, which finds its reflection in the rapid growth of prices. We shall take the average price of the free markets for 2,700 calories of the ordinary food ration, as gathered by Greman’s Committee from some 20 or 30 small towns up to April 1920 and compare them with the price of same in 1913, which we shall take as a basis. We then find that in the first quarter of 1918, in the first period of the Bolshevist revolution, this price was 23 times higher than in 1913. This makes it possible to measure the paper money inflation for the period of the imperialist war. Over a year after, in the second quarter of 1919, it was 243 times higher than in 1313 and for the third quarter of 1919. 468 times, in the first quarter of 1919 449 and in the first quarter of 1920, 2,103. From this endless untoward tendency the Soviet Government can shake itself free, by abolishing settlements of accounts in the movement of commodities within the limits of one undertaking and where a monetary account is not necessary, but only an account of commodities, just as the mother of a family during a meal does not settle accounts with the children for the soup ladled out but simply gives every child its dues here. It is a very characteristic example of the gradual development of the efficiency of the Soviet machinery, that whilst in the first years, it was impossible to accomplish such a measure now (11th October 1920) the Council of People’s Commissaries has deemed it possible to abolish payment for all goods without exception (foodstuffs as well as manufactured goods) supplied by the Government to workmen, employees and their families, as well as for living rooms, fuel, gas, electricity, telephone, water, railway fare, etc. It is equally deemed possible to abolish very shortly, all money payments between industrial undertaking, for raw material semi-products etc., and also between the distributive organs and all Soviet institutions. Money is for the present limited to purchases in the “free market,” which however is naturally shrinking in the measure as produce is being concentrated in the hands of the State. With the increase of the output of manufactured goods, the State will be in a position to settle accounts with the peasants for their produce and for their services, such as felling and carrying timber etc., in kind instead of in currency (first steps in this direction are already being made).

The building up of the Soviet system of public economy is not nearly completed yet, and a number of problems await final solution. Many essentials could not be touched on in this article for lack of space. For instance we have said nothing about so important a fact as the setting up of a few thousand large Soviet estates covering a total area of about 4 million hectares, or of new features of economic life such as the recent labour mobilisation of three classes, or of “production propaganda” etc. At any rate, many paths have been opened during these three years, in the work of construction and the tendency of future development is quite clear. The population of Russia is at present materially worse off than it was before the war, but of the first Soviet State has stood the test of three years and as a result “The State of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat” enters upon the fourth year stronger than ever, and ready further to fulfil its historical mission.

21st October 1920.

Truth emerged from the The Duluth Labor Leader, a weekly English language publication of the Scandinavian local of the Socialist Party in Duluth, Minnesota and began on May Day, 1917 as a Left Wing alternative to the Duluth Labor World. The paper was aligned to both the SP and the IWW leading to the paper being closed down in the first big anti-IWW raids in September, 1917. The paper was reborn as Truth, with the Duluth Scandinavian Socialists joining the Communist Labor Party of America in 1919. Shortly after the editor, Jack Carney, was arrested and convicted of espionage in 1920. Truth continued to publish with a new editor JO Bentall until 1923 as an unofficial paper of the CP.

Access to full issue: https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn89081142/1921-01-14/ed-1/seq-2