Lenin surveys initial reactions to the First World War by Socialist papers, mostly those associated with Russian exile communities, including Golos, Paris organ of then Menshevik Internationalists like Martov and Trotsky; Berner Tagwacht, Berne paper of the Swiss Social-Democratic Party initially sympathetic German left internationalists like Liebknecht and Mehring; the Hamburger Echo, a chauvinist German Social-Democratic paper; and Mysl, Chernov’s Socialist-Revolutionist internationalist paper, among others. Printed on December 23, 1914 in Sotsial-Demokrat, revived by Lenin while in Swiss exile, a country home to many Russian revolutionaries, in 1914. The paper became lead literary vehicle in the polemics that would help define the need for and politics of the new Third International.

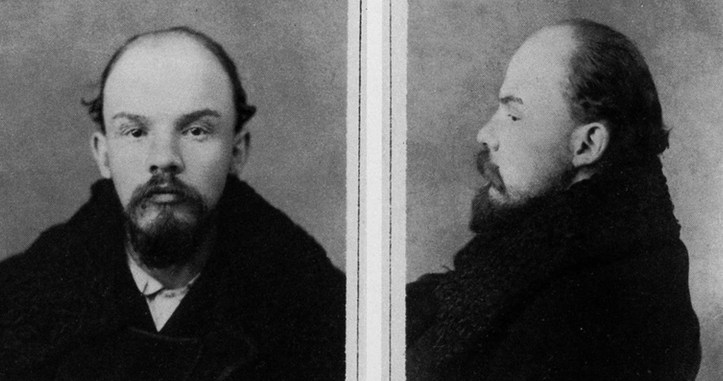

‘And Now What? Tasks of the Workers’ Parties Relative to Opportunism and Chauvinism’ (1914) by V.I. Lenin from Collected Works. Vol. 18. International Publishers, New York. 1930.

The stupendous crisis within the ranks of European Socialism which came in consequence of the World War has first resulted (as is always the case in great crises) in enormous confusion; then there began to take shape a series of new groupings among the representatives of various currents, shades and views in Socialism; finally, there has been raised, with particular acuteness and insistence, the question of what changes in the foundations of Socialist policy follow from the crisis and are demanded by it. These three “stages” were passed, between August and December, 1914, also by the Socialists of Russia in a marked fashion. We all know that at the beginning there was no little confusion; the confusion was increased by the tsarist persecutions, by the behaviour of the “Europeans,” by the war alarm. In Paris and Switzerland, where there was the greatest number of political exiles, the greatest number of connections with Russia and the greatest amount of freedom, a new definite line of demarcation between the various attitudes towards the problems raised by the war was being drawn in discussions, at lectures, and in the press during September and October. We may safely say that there is not a single shade of opinion in any current (or faction) of Socialism (and near-Socialism) in Russia which has not been expressed or analysed. Everybody feels that the time is ripe for definite and positive conclusions to become the basis of new, systematic, practical activity in the field of propaganda, agitation, organisation. The situation has become clear, indeed: everybody has expressed himself. Let us now see who is with whom and whither he is bound.

On November 23, one day after the publication in Petrograd of a governmental communiqué regarding the imprisonment of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Fraction, in Stockholm, at the conference of the Swedish Social-Democratic Party, an occurrence took place which finally and irrevocably placed on the order of the day the two questions just mentioned. The readers will find below a description of this occurrence, namely, a full translation, from the official Swedish Social-Democratic report, of the speeches both of Belenin (representative of the Central Committee) and of Larin (representative of the Organisation Committee) also the debate on the question raised by Branting.

For the first time after the beginning of the war, a representative of our party, of its Central Committee, and a representative of the Liquidationist Organisation Committee, met at a congress of Socialists of a neutral country. How did their speeches differ? Belenin took a most definite stand regarding the grave and painful yet momentous questions of the present-day Socialist movement; referring to the Central Organ of the party, the Sotsial-Demokrat, he resolutely declared war against opportunism, branding the behaviour of the German Social-Democratic leaders (and “many others”) as treason. Larin took no position at all; he passed over the essence of the question in silence, confining himself to those hackneyed, hollow and foul phrases which do not fail to be rewarded with applause by the opportunists and social-chauvinists of all countries. Belenin kept complete silence concerning our attitude towards the other Social-Democratic parties and groups in Russia, as if saying: “This is our position, and as to the others, we shall not express ourselves as yet, we shall wait to see which course they will take.” On the other hand, Larin unfurled the banner of “unity,” shedding a tear over the “bitter fruits of disunity in Russia,” painting with gorgeous colours the “unity work” of the O.C., which, he said, had united Plekhanov and the Caucasians, the Bundists and the Poles, and so forth. Larin’s intentions will be treated elsewhere. (See below: “What Unity Has Larin Proclaimed?”) What interests us here is the fundamental question of unity.

We have before us two slogans. One is war against the opportunists and social-chauvinists as traitors. Another is unity in Russia, particularly with Plekhanov (who, parenthetically, behaves among us exactly as Sudekum1 among the Germans, Hyndman among the English, etc.). Is it not obvious that, while afraid to call things by their right names, Larin, in reality, appeared as an advocate of the opportunists and social-chauvinists?

But let us analyse the meaning of the “unity” slogan in general in the light of the present events. Unity of the proletariat is its greatest weapon in the struggle for a Socialist revolution. From this undisputed truth it undisputedly follows that when a proletarian party is joined by a considerable number of petty-bourgeois elements, which interfere with the struggle for a Socialist revolution, unity with such elements is harmful and detrimental to the cause of the proletariat. Present events have proven this very fact that objective conditions for an imperialist war (i.e., a war corresponding to the highest and last stages of capitalism) are ripe; that, on the other hand, decades of a so-called peaceful epoch have allowed a heap of petty-bourgeois opportunist refuse to accumulate inside of the Socialist parties of all European countries. Some fifteen years ago, during the famous “Bernstein crusade” in Germany—in many countries even earlier than that—the question of the opportunist, the foreign, elements within the proletarian parties had become acute. There is hardly one noted Marxist who has not recognised many times and on different occasions that opportunists are a non-proletarian element actually hostile to the Socialist revolution. The rapid growth of this social element during the last years is a recognised fact; the officials of the legal labour unions, the parliamentarians and the other intellectuals who comfortably and placidly built themselves berths in the legal mass movements, some groups of the best paid workers, office employees, etc., etc., belong to this social stratum. The war has clearly proven that in a crisis (and the imperialist era will undoubtedly be an era of such crises) a substantial mass of opportunists, supported and often directly guided by the bourgeoisie (this is particularly important!) goes over to its camp, betrays Socialism, harms the workers’ cause, ruins it. In every crisis the bourgeoisie will always aid the opportunists, will always suppress the revolutionary portion of the proletariat, shrinking before nothing, employing the most lawless and cruel military measures. The opportunists are bourgeois enemies of the proletarian revolution. In peaceful times they conduct their bourgeois work under cover, finding refuge inside of the workers’ parties; in times of crisis they appear immediately as open allies of the entire united bourgeoisie from the conservative to the most radical and democratic part of it, from the freethinkers to the religious and clerical sections. He who has not grasped this truth after the recent events is hopelessly deceiving himself and the workers. Personal desertions are unavoidable under given conditions, but one must not forget that their significance is determined by the existence of a group and current of petty-bourgeois opportunists. Such social-chauvinists as Hyndman, Vandervelde, Guesde, Plekhanov, Kautsky, would be of no importance whatever if their characterless and trite speeches in defence of bourgeois patriotism were not grasped at by whole social strata of opportunists and by hosts of bourgeois papers and bourgeois politicians.

There prevailed in the epoch of the Second International the type of Socialist party that tolerated in its midst an opportunism accumulated through decades of the “peaceful” period, an opportunism that was hiding its real face, adapting itself to the revolutionary workers, adopting their Marxian terminology and avoiding a clear demarcation on principles. This type has outlived itself. Suppose the war should end in 1915; is there any one among thinking Socialists who would be willing to undertake in 1916 the restoration of the workers’ parties, including the opportunists, knowing from experience that in a new crisis all of them (plus many other characterless and confused people) will be for the bourgeoisie, which, of course, will find a pretext to prohibit the mention of class hatred and class struggle?

In Italy, the party was an exception to the rule in the epoch of the Second International: The opportunists, with Bissolati at their head, had been removed from the party. The results, during the present crisis, proved excellent: Men of various trends of opinion did not deceive the workers, did not throw into their eyes luxurious flowers of eloquence regarding unity, but followed each his own road. Opportunists (including traitors who ran away from the workers’ party, like Mussolini) practised social-chauvinism, praising (like Plekhanov) “gallant Belgium” and therewith shielding the policies, not of a gallant, but of a bourgeois Italy which intends to plunder the Ukraine and Galicia…no, pardon, Albania, Tunis, etc., etc. At the same time, the Socialists, in opposition to them, waged war against war, preparing civil war. We are not at all inclined to idealise the Italian Socialist Party. We do not at all guarantee that it will remain perfectly solid in case Italy enters the war. We do not speak of the future of this party; we speak only of the present. We state the undisputed fact that the workers of the majority of the European countries find themselves deceived by the fictitious unity of opportunists and revolutionists, and that Italy is a happy exception, a country where there is no deception at the present time. The thing that was a happy exception for the Second International must and will become a rule for the Third. As long as capitalism persists, the proletariat will always be a close neighbour to the petty bourgeoisie. It is not clever, sometimes, to refuse temporary alliances with it, but unity with the opportunists can at present be defended only by the enemies of the proletariat or by deceived routineurs of the past epoch.

Unity of the proletarian struggle for a Socialist revolution demands now, after 1914, an unconditional separation between the workers’ parties and the party of the opportunists. What we understand by opportunism has been clearly said in the Manifesto of the Central Committee (War and Russian Social-Democracy.)

But what do we see in Russia? Is it good or bad for the labour movement of our country to have unity between people who, in one way or another, with more or less consistency, are fighting against chauvinism—both the Purishkevich and the Cadet brand of it—and people who sing in unison with the same chauvinism, like Maslov, Plekhanov and Smirnov? Is it good to have unity between people who act against the war and people who declare that they will not act against the war, like the influential authors of the “Document” (No. 34)? Only those who wish to keep their eyes shut can find difficulty in answering this question.

One may point out that Martov has entered into polemics with Plekhanov in the Golos and with a number of other friends and partisans of the Organisation Committee, also that he has battled against social-chauvinism. We do not deny this, and we have ungrudgingly praised Martov in No. 33 of the Central Organ. We should be very glad if Martov would not be “turned around” (see note, “Martov Turns Around”); we would like very much that a decisive anti-chauvinist line should become the line of the Organisation Committee. But this does not depend upon our wishes, or any one else’s for that matter. What are the objective facts? Firstly, the official representative of the Organisation Committee, Larin, for one reason or another, keeps silent about the Golos while mentioning the social-chauvinist, Plekhanov, and also mentioning Axelrod, who wrote one article (in the Berner Tagwacht [Berne Daily Sentinel]) in order not to say a single definite word there.

We must not forget that, besides his official position, Larin is more than geographically close to the influential central group of the Liquidators in Russia. Secondly, there is the European press. In France and Germany, the papers keep quiet about the Golos while speaking of Rubanovich, Plekhanov and Chkheidze (the Hamburger Echo [Hamburg Echo], one of the most chauvinist organs of the chauvinist “Social-Democratic” press of Germany, in its issue of December 12, called Chkheidze an adherent of Maslov and Plekhanov; this was also hinted at by some papers in Russia. It is easily understood that all the conscious friends of the Sudekums fully appreciate the ideological aid rendered by Plekhanov to the Sudekums). In Russia, millions of copies of bourgeois papers bring the “people” tidings of Maslov—Plekhanov—Smirnov—and no news of the current represented by the Golos.Thirdly, we have the experience of the legal workers’ press of 1912-1914, which definitely proved that the source of a certain degree of social power and influence manifested by the liquidationist movement is to be found not in the working class but in that group of the bourgeois-democratic intelligentsia which pushed to the front the central group of legalist writers. Witness to the national-chauvinist tendency of this group as a group is the whole press of Russia, as revealed in the letters of the Petrograd worker (Sotsial-Demokrat Nos. 33-35) and in the “Document” (No. 34). Important personal re-groupings within that group are easily possible, but it is entirely improbable that, as a group, it should not be “patriotic” and opportunist.

Such are the objective facts. Reckoning with them, and knowing that it is good for all bourgeois parties craving influence over the workers to have a Left Wing for exhibition (especially when it is not called so officially), we must declare the idea of unity with the Organisation Committee an illusion detrimental to the workers’ cause.

The policy of the Organisation Committee which, in far-away Sweden, on November 23, declares its unity with Plekhanov and delivers speeches sweet to the hearts of all social-chauvinists, while in Paris and in Switzerland it does not make its existence known either on September 13 (when the Golos appeared) nor on November 23, nor after this to the present time (December 23), is very much like the worst kind of political maneuvering. The hope that the Ozkliki [Echo], scheduled to appear in Zurich, would have an official party character, has been destroyed by a direct statement in the Berner Tagwacht (December 12), to the effect that this paper would have no such character. (Apropos, the editors of the Golos declared in No. 52 that to continue at present the split with the Liquidators would be “nationalism” of the worst kind. This phrase, being devoid of grammatical sense, has the one political meaning that it reveals the editors of the Golos as preferring unity with the social-chauvinists to a closer relation with those who are irreconcilably hostile to social-chauvinism. The editors of the Golos have made a bad choice.)

To make the picture complete, we must say in conclusion a few words about the organ of the Socialists-Revolutionists, Mysl [Thought], which appears in Paris. This paper also sings the praises of “unity” while shielding (compare the Sotsial-Demokrat, No. 34) the social-chauvinism of its party leader Rubanovich, defending the Franco-Belgian opportunists and ministerialists, passing in silence over the patriotic motives of the speeches of Kerensky, one of the extreme radicals among the Russian Trudoviks, and printing unspeakably hackneyed petty-bourgeois vulgarities on the revision of Marxism in a Narodnik and opportunist direction. The things said about the Socialists-Revolutionists in the resolution of the summer conference of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party in 1913 have been fully and repeatedly proven by this behaviour of the Mysl.

Some Russian Socialists seem to think that internationalism consists in readiness to embrace a resolution containing an international vindication of social-chauvinism of all countries, such as is about to be composed by Plekhanov and Sudekum, Kautsky and Hervé, Guesde and Hyndman, Vandervelde and Bissolati, etc. We allow ourselves to think that internationalism consists only in an unequivocal internationalist policy pursued inside the party itself. In company with opportunists and social-chauvinists it is impossible to pursue the true international policy of the proletariat. It is impossible to preach active opposition to war while gathering the forces for the war. To seek refuge in silence, or to wave away this truth which, though bitter, is unavoidable for a Socialist, is detrimental to the labour movement.

1. Plekhanov’s pamphlet, On the War 58 (Paris, 1914), which we have just received, proves very convincingly the truth of the assertions made in the text. We shall return to this pamphlet later on.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/leninvolumexviii0000vlad/leninvolumexviii0000vlad.pdf