Dutch Communist Willem van Ravesteyn with a fine essay on the emergence of oil as the preeminent post-WWI commodity; the source of enormous wealth and power, as well as much of the world’s instability and conflict. In particular, the role of Royal Dutch Shell is examined.

‘Oil, The Super-Government’ by Dr. W. van Ravesteyn from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 2 No. 16. February 28, 1922.

It well known how petroleum seeks to consume the world in flames even before it sees the light of day. Ever since we learned the use of liquid fuel, of oil as fuel for ships, and saw that it is more yielding than the coal whose strategic significance it displaced, the search for oil has become very lively. Thus it has become for imperialism the most important product in the world.

In Delaisi’s “Le Pétrole”, published in French in 1920, it was pointed out that after the war, “victorious England” saw a dangerous rival in the United States, chiefly because of the latter’s oil-treasures and extensive use of petroleum. However, England, whose former efforts in Mexico, Mesopotamia, Persia, etc. are only too well known, has since then succeeded in annexing the most important oil fields through diplomacy. Delaisi’s publication itself discloses the machinations by means of which the powerful Shell trust, by attracting the private interests e of the French Stock Exchange, succeeded in drawing France of into its sphere of activity. Delaisi complains that this nipped the development of the independent French industries, which could lay claim to extensive and rich fields of exploitation, particularly in Africa, and after peace was concluded, in Roumania, Galicia and Russia as well as in the Orient; here it was again the banking system, which in France is not connected with the industries, that hemmed instead of furthering their development.

The English trust acquired its great significance only after its combine with the “Royal Dutch Shell” (a corporation for the exploitation of the oil fields in the Dutch East Indies) which had also acquired control of many oil fields in the rest of the world. From that time on the English-Dutch trust is known the world over as the “Royal Dutch Shell”. This giant rose side by side with the American “Standard Oil”, creation of Rockefeller, and both monsters were to share the petroleum-world between themselves. Only the Soviet states remained outside the domain of these rulers.”

English diplomacy was able to acquire most of the world’s oil fields “on the quiet”. In October 1919, when the Standard Oil set out in search of new fields of exploitation, it found all doors shut; the Royal Dutch Shell had even laid hands upon a considerable number of American oil-wells, whereas English legislation, carefully kept foreigners away from British oil-fields.

This shutting of the world to the American oil-trust, was confirmed in the American Senate in March 1920, and in May of the same year by the United States Government itself. The Royal Dutch Shell, answering through the London “Times”, admitted that it was true that “the English already possessed 2/3 of all the oil-wells in the old world and in Central and South America, and that in about 10 years the Americans would have to import 500 million barrels at one million dollars yearly”. And as a matter of fact, even though the Standard Oil still produces three times as much as the Royal Dutch, we must not forget that due to the immense national consumption (especially of gasoline, 85% of which is consumed by the 8,000,000 automobiles within the country) the American oil-reserves (about 7,000,000,000 barrels) are rapidly being exhausted, whereas the English already control the greater part of the rest of the world’s oil-reserves, estimated at about 55,000,000,000 barrels.

Of course, when the distressed Standard Oil looked around for new fields of exploitation, the American government (which for strategic reasons, is in this case even a direct participant) backed it. Of the American Government’s efforts in this matter we need but recall its contest with England in Mesopotamia, where England had a better position, and its agreement with Colombia in April 1921, entered into for the express purpose of drawing the immense oil-fields, supposed to be there, into its sphere of interests.

It is very instructive to examine a typical example of how the trusts get a government–yes, and an independent and democratic government at that!–into its clutches.

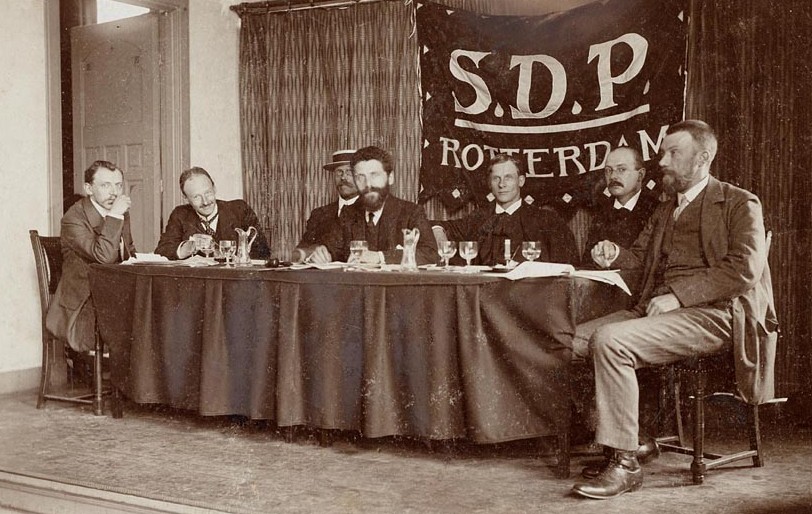

As early as 1900, the Standard Oil sought concessions on the island of Sumatra, one of the Dutch East Indies. But the Batavian Company, a subsidiary of the Royal Dutch Shell got the concession. In the Djambi district there are very rich virgin oil-fields covering an area of about 4,418,000 acres. In 1915, the Dutch government was again willing to grant the monopoly of these oil-fields to the Batavian Company, this in spite of the fact that the company was not the highest bidder. But the proposed bill found strong opposition in the press as well as in Parliament; it was claimed by the opposition that the Batavian Company was in spite of its Dutch name really an organ of the powerful Royal Dutch Shell and that such a step would mean the drawing in of English capital, which with a product so important from the strategic point of view might place the country in a dangerous position. Parliament even went so far that although the majority of its members far from favored the idea of government exploitation, the Social Democratic bill which aimed at this passed the house as a sort of last resource. The social patriots were jubilant over their “victory”; they were not aware, however, of the simple truth that it is not Parliaments that govern countries. “The life-interests of nations”, as Delaisi rightly points out, “are determined by the business methods of financial groups by whom they are secretly ruled”. Nothing came of the government exploitation. “A minister is not obliged to heed a whim of Parliament…” was the ironic remark passed by a capitalist newspaper. Once more the government made an attempt to let the Batavian Company in through the backdoor–all too obviously however, for it to have any chance of success. But the trusts did not yield.

World capital kept on “working on the quiet”. And in April 1921, when the government once more proposed a bill, the writer of this article, who was shedding light on the matter from our standpoint, was at that time convinced that due to the country’s passivity, the whole matter had by that time surely been settled and cleared up behind the scenes. That this opinion was correct we saw later on when we learned from official documents that early as January when only a draft of the bill had been handed in, the government considered the matter as “concluded and passed until Parliament gives its approval”…a mere trifle apparently.

This time the government proceeded more cautiously. Its bill only proposed the founding of a corporation half of whose shares was to be in the hands of the government and the other half of whose shares was to be sold to private individuals to be named later on. How perfectly innocent and harmless! But the matter assumed a different complexion when the government was compelled to admit that the “private person” in question was no other than the Batavian Company, a branch of the Royal Dutch Shell.

No wonder then that this new proposal was not met with open arms either; the “capitulation before the Royal Dutch Shell” was spoken of. But does this mean that the bill was defeated? Not by a long shot! It is interests and not words that decide.

Yet, there were other truly good reasons for defeating the bill. At every step the government was caught–“committing errors”.

Then, by some unfortunate mistake, a piece of paper found its way among the documents, which gave away to the trust not only the Djambi fields, but all the oil fields in the whole of the Dutch East Indies. But it is of major interest to note here that the government persisted in denying the all-too-well-known fact that the Royal Dutch Shell was a representative of English capital, and constantly maintained that it was rather a “purely Dutch enterprise”! On the other hand the government pretended not to believe that the American government had any interest in the matter and that it stood behind the Standard Oil which was urging free competition. Our comrades demanded in the name of the Dutch proletariat and the oppressed inhabitants of the East Indies that the exploitation of the fields be postponed until the time when the East Indies, the true owners of these natural treasures, should become an independent nation. Of course, the social patriots attempted to ridicule this viewpoint. The Communist motion received only the votes of our own comrades.

But what is still more significant is that the whole bill was passed in spite of everything. It soon appeared that we were right. Not only did the American press assume a harsh tone towards us, but it even appeared that the government had simply hushed up a very important correspondence with the American government! This correspondence disclosed that the Americans had repeatedly pointed out their interest in the matter in question and that they protested against the manner of treatment, where upon the Dutch government began to play the ingenuous child and never answered to the point.

This naturally brought on a cloudburst. Parliamentarism of all colors wailed that “had they but known all this” they would have thought the matter over a second time. The largest liberal newspaper wrote that a Parliament which stood for such treatment deserved to be the laughing-stock of the country. The Communist proposal to vote the whole government out of existence was rejected. Even a vote of criticism against the Colonial Secretary, upon whom no love is lost anyhow, did not receive a majority, so that this minister is still at his post and was later even eulogized for this “behavior” in this matter. All further motions which sought to revive this affair were pigeon-holed.

But how was all this possible? To begin with we must not lose sight of the fact that today Dutch capital toadies to Allied capital just as much as in times of old it fawned upon German imperialism to whom a Royal Dutch Shell victory was surely not the sweetest of pills to swallow. Furthermore, not very much was left of that group which had formerly wanted the concession for itself; one of them, who had previously given warning of the plans of the Royal Dutch Shell, had in the meanwhile been driven from public life by the dummies of the almighty trust (the official grounds were given as “political moral discipline”…) Be it furthermore remembered that two ex-ministers and former governors of the East Indies, who are at present leaders of the government parties, Colyn and Idenburg, were at the time of the Parliamentary negotiations in question, appointed directors of the Batavian Company and later of the Royal Dutch Shell itself, whereas at the same time a third ex-minister and brother-in-law of the present Minister of Foreign Affaires received a very high position in the trust. Besides these the Royal Dutch has on its board of directors former high government officials from the Dutch East Indies. The profits of these gentlemen runs into the millions of gulden. Mr. Colyn seems to have transacted similar deals even when still in office. Is it any wonder then, that our comrades cried out in Parliament, “Every mother’s son of them is sold?”

Thus capitalism roots out the Netherlands, and what still remained intact after the war it will root up in the future, if–if the international proletariat does not prevent it in time.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecor” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecor’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecor, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. A major contributor to the Communist press in the U.S., Inprecor is an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1922/v02n016-feb-28-1922-inprecor.pdf