An early entry on a topic Fraina would return to repeatedly over the following decade as he sought to explain the imperialist history of the United States as it emerged into a preeminent power.

‘The Monroe Doctrine’ by Louis C. Fraina from New Review. Vol. 1 No. 22. November, 1913.

The Panama Canal, sired by imperialistic plutocracy, was initially considered chiefly as a tool for the commercial conquest of the Orient. Since President Wilson repudiated the “Six Power Group” China loan, his Administration has shown that it considers the Canal chiefly in relation to Latin America. The Democratic Administration aims to unlock “the double-bolted door of opportunity” for the lesser capitalists, who, while not powerful enough to engage in imperialistic adventures in China, may still draw good profits from trade with South America, which is a big field for small exporters. There is less risk and a freer opportunity for all. The result is a new and larger interest in South America.

While most of the Caribbean states, notably Santo Domingo, Nicaragua, Honduras, and even Venezuela, are a satrapy of American high finance, American capital faces the unpleasant fact that it secures no more than 15 per cent, of South America’s foreign trade. The activity of American interests in Central America has been that of financial brigands. This has aroused the antagonism and distrust of South America. Nor does the United States adopt efficient methods in its trade with South America. While England, France and Germany have a chain of banks in South America, there is not an American bank south of Panama. A growing sentiment, however, considers the Monroe Doctrine the most important factor in the situation.

For South America sees in the Monroe Doctrine an insult and a menace, and suspects the United States to be scheming a Pan-American empire. Prof. Bingham’s book* is an interesting contribution to this view.

The point stressed in this book is that the new Monroe Doctrine, developed for the commercial and political supremacy of the United States in the New World, has failed of its object; that while potent in Central America, it has greatly injured our trade with South America, and practically banded Argentina,

Brazil and Chile against the United States. As originally laid down, the Monroe Doctrine contemplated the exclusion of “future colonization by European powers” on the American continent. The young Republic, fearing the monarchical reaction in Europe and the schemes of the Holy Alliance, aimed to protect its own independence by protecting that of the other American republics. Later, however, the Doctrine became an instrument of aggression. In 1895, during the Venezuelan dispute with Great Britain, Cleveland’s Secretary of State Olney proclaimed a new principle and new version of the Monroe Doctrine: that the “United States is practically sovereign on this continent, and that its fiat is law upon the subject to which it confines its interposition.” This was followed by the spoliation of Spain in Cuba, in 1898, thereby violating that clause in the original Doctrine providing that the United States “shall not interfere” with “the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power.”

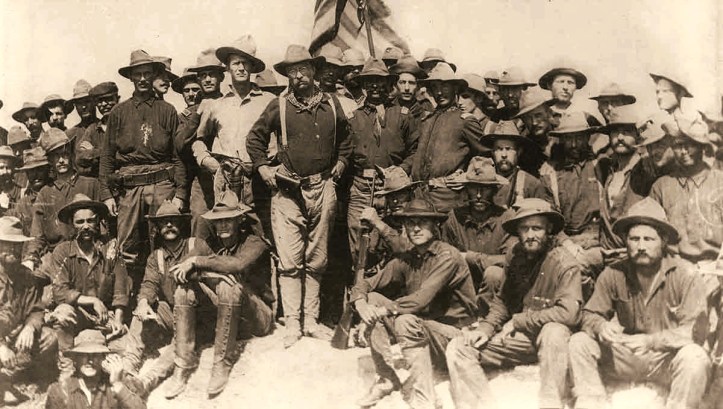

Thereafter the United States has continuously terrorized Latin America. Mr. Bingham treats this phase very mildly. As a matter of fact, President Roosevelt not only turned the Monroe Doctrine into such a totally new thing as to suggest a new name, the “Roosevelt Doctrine,” but his Administration also established a virtual and ubiquitous protectorate in Central America. Mr. Bingham slurs over the vicious facts of the “Roosevelt Doctrine.” Indeed, he largely though indirectly condones its policy in Central America. Of the seizure of Santo Domingo’s customs houses, which act turned the United States into a debt- collecting agency for Europe, he says, “We may seem to have been justified in our course.” Surely mild language!

Prof. Bingham objects to the Monroe Doctrine because the antagonism it rouses in South America reacts injuriously upon United States trade. Argentina, Brazil and Chile are strong enough to resent United States tutelage. They consider the present Monroe Doctrine a “petulant and insatiable imperialism,” the “shield and buckler of United States aggression.” They believe the United States wishes to dominate the American continents. A vigorous sentiment urges them to ally in defense. And while Bingham scoffs at the legitimacy of these fears, he holds that they injure the United States commercially. “Why spoil the game by an irritating and antiquated foreign policy which makes it easier for our competitors and harder for our own merchants?”

South America is a vast field for trade. Mr. Bingham indicates that it is commercially more important to the United States than the Orient: “Our imports from China and Japan in 1910 amounted to 81 million dollars. Our imports from Argentina and Brazil amounted to 129 million dollars.” Argentina and Brazil “imported $650,000,000 worth of goods last year (1912) and had $200,000,000 left over.” Chile spends millions on internal improvements. Argentina exports more agricultural products than the United States. Great Britain has $4,573,243,200 invested in Latin America, $2,973,760,000 in Argentina, Brazil and Chile alone. Bingham fears that the United States may be left out in the cold. He emphasizes Germany’s “peaceful conquest of South America,” and the rising tide of Oriental immigration. Argentina and Brazil offer inducements to Japanese immigrants, and there are 15,000 Chinese in Peru who “readily assimilate with the Peruvians.”

In view of all the facts, Mr. Bingham urges an alliance between the United States and Argentina, Brazil and Chile, which shall preserve “America for the Americans.” The Monroe Doctrine should be buried, and friendship supersede tutelage.

It appears that this new policy would not include Central America and the small Southern republics. The new alliance would lord it over the rest of the continent, assuring peace–and the spoils. Except this exclusion from the scope of the Monroe Doctrine of Argentina, Brazil and Chile, the status quo would be maintained. The brigands of high finance in Central America need have no fear!

Is Mr. Bingham’s suggestion the precursor of a new Latin-American policy, or is he a voice crying in the wilderness?

The development of the Monroe Doctrine parallels the development of American capitalism into plutocracy. While Polk and Grant modified the Doctrine, it was not until the late 80’s and early 90’s that the Monroe Doctrine was fundamentally changed and turned into a travesty of the original. The dominantly plutocratic administration of Roosevelt completed the change. It might be reasoned, accordingly, that a non-plutocratic, Democratic administration would let fall the later imperialistic implications of the Doctrine into harmless desuetude.

There is, however, involved another and corollary fact. The Democratic party has never opposed imperialism in Latin America. The Democratic Cleveland as much as the Republican Roosevelt turned the Monroe Doctrine into an imperialistic instrument. Imperialism in the Orient has been exorcised by the Wilson Administration, but blessed in Latin America. Secretary of State Bryan proposed an American protectorate over Nicaragua. In October the American Minister to the Dominican Republic compelled warring factions to make peace. This “first successful application of our new Latin-American policy” implies that “in future any uprising will be stamped out as criminal without a conference being held between the opposing factions, the United States supporting the constitutional authority.” The Democratic Congress voted larger naval appropriations than its Republican predecessor; and the Democrats now propose three battleships a year, while the Secretary of War urges a larger and more efficient army. This is imperialism with a vengeance!

There is another important fact. John Barrett, Director- General of the Pan-American Union, recently pointed out that United States trade with South America since 1900 has increased 197 per cent., while European increase was very much less. The largest gain was in trade with Argentina and Brazil. The new tariff has encouraged South American exporters, particularly Argentinian, and they are studying our markets. The American capitalist, compelled by the new tariff to meet foreign competition, is organizing systematic invasions of foreign markets, and has decided that South America offers a great opportunity. Indications, accordingly, point to a phenomenal increase in trade between South America and the United States. With this condition, and Democratic imperialism, the usually short-sighted American capitalist may let well enough alone, and not tamper with the Monroe Doctrine.

An alliance with Argentina, Brazil and Chile would undoubtedly prove advantageous to the commerce of the United States. And as this alliance would not necessarily mean the end of American imperialism, the Monroe Doctrine may be modified accordingly, but not immediately. A modification must take place sooner or later. The suggestion of such a modification is another symptom of the readjustive trend in American capitalism.

*The Monroe Doctrine: An Obsolete Shibboleth. By Hiram Bingham. New Haven: Yale University Press.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1913/v1n22-nov-1913.pdf