Allan Pinkerton is one of U.S. history’s most nefarious characters. As part of his Government by Gunmen series, Turner looks at the anti-labor, public/private legal system, even a whole political culture, developed under Pinkerton from after the Civil War, through the Molly Maguires, Homestead, and to the Western Federation of Miners of his time. We are still very much living in a world crafted by this man, who made a fortune, slandering, framing-up and murdering those attempting to better the lot of working people.

‘Gunman Pinkerton First to Serve Mammon’ by John Kenneth Turner from Appeal to Reason. No. 965. May 30, 1914.

GOVERNMENT BY GUNMEN, as the perfected piece of machinery that we find in the year 1914, was not thought out all at once by some hideous Satanic genius. Like other complicated devices, mechanical and social, it is a product of growth extending over a considerable period of time.

I have called Government by Gunmen new. It is new insofar as the generality of its application is concerned. Never before has it been brought into play so widely, so boldly, so ruthlessly, so systematically and so effectively as during the past two years.

Yet to find the beginnings of Government by Gunmen we have to go back half a century. By reason of its employment in labor crises in past decades there have been a number of bloody battles, many bereaved homes, strikes broken, organizations of workingmen smashed.

In following the story of Government by Gunmen, remember always that it is an institution peculiar to America. Not even Russia has it; not even Mexico. Our northern neighbor, Canada, does not permit it. No other civilized nation permits it. It belongs to feudalism. Only in our “sweet land of liberty” are private armies raised, trained, and fought as a regular business. Here the duly constituted authorities not only fail to suppress the thing, but they aid and protect it.

System Is Unlawful.

Remember, also, that the whole system could easily be suppressed, since it is clearly unlawful. The individual, in hiring persons to perform the duties of police or soldier, usurps the special functions of the state. This is against public policy, in violation of the common law, and a direct infringement of the basic principles of constitutional government.

Moreover, every concern in the country dealing in private soldiers could be put out of business under the existing statutes. They could be convicted under the conspiracy laws, provided the present office holders wished to convict them.

It can be proved to the satisfaction of any honest court and of any untrammeled jury that every one of these concerns, licensed as “detective agencies,” and in business to war on labor, are criminal conspiracies to commit murder and other felonies.

Then why has not the system been suppressed? Why is Government by Gunmen?

Because it has done and is doing a work that the ruling class wants done. It has kept labor cheap; it has prevented the working people from organizing; it has staved off the triumph of Socialism.

Father of Gunmen.

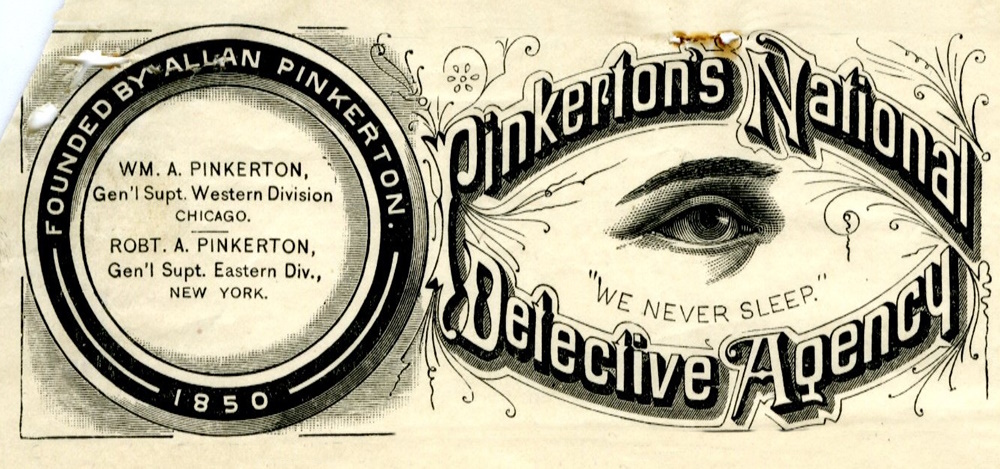

Allan Pinkerton may be called the father of Government by Gunmen. This man had been a city detective in Chicago, and afterwards chief special agent of the federal government in the mail service. In 1850 Pinkerton abandoned public sleuthing for private sleuthing, opening an office in Chicago. His evolution from a bona fide detective to a specialist in labor spying and strike-breaking was rapid. His first step was to furnish what he called “watchmen.” A labor division was his next departure. He branched off into furnishing scabs. Finally he arrived at the gunman stage.

This “great detective” of a former generation made a careful study of the public police spy system of European countries, and adapted what he learned to the private police and strike-breaking business in this country. While practicing nearly every art known to–and perfected by the professional strike-breaker of the present day, Pinkerton was especially strong on agent provocateur stunts, a rising apostle of which in this day is another “great detective,” an imitator of Pinkerton in other respects–William J. Burns.

While his spies were in every prominent labor union in the land, attempting to incite men to violence, in order to “get” them, and when they failed to incite them, then manufacturing “frame-ups,” Allan himself was writing books of his achievements.

Painted Workers as Villains.

These pretended histories were in reality highly colored romances, in which Pinkerton and his underlings were the shining heroes, and union men the villains. Melodrama has never painted villains blacker than Pinkerton painted the poor, struggling working-man of the 70’s. In these romances the detective author sought to make the nation look upon all labor unions a secret conspiracies against the state, and himself as the champion and savior of the state. The books served as a means of advertising the “National Detective Agency” and at the same time as a defence of the crimes perpetrated by it.

The first industrial struggle in which Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency furnished gunmen was a strike of miners at Braidewood, Ill., in September, 1866. The rapidity with which the agency grew, in a few years, as a concern for carrying on private warfare, was disclosed by a special committee of the United States senate, appointed in 1892, as a result of the Homestead battle. Robert A. Pinkerton, a son, confessed to the following information:

His agency had up to that time furnished men in 70 strikes:

Had been opposed in the field to more than 125,000 workingmen;

Had on the pay-roll between 500 and 600 office employes, solicitors, etc.;

Maintained a reserve army, numbering thousands, which could be assembled quickly and rushed to a given point without delay;

Possessed private arsenals, equipped with rifles and other arms, said arms being for use in labor troubles.

The Pinkerton armies marched about in special uniforms and did their fighting in them. This contributed to a general impression that the organization was a legal and official concern. With the exposures following the Homestead battle the uniform was done away with and thenceforth America’s private armies have carried on their terrible work behind the mask of ordinary clothing. (With such exceptions as that at present found in Colorado, where, to fit the circumstances, a private army was mustered bodily into the state militia.)

The “Molly Maguires.”

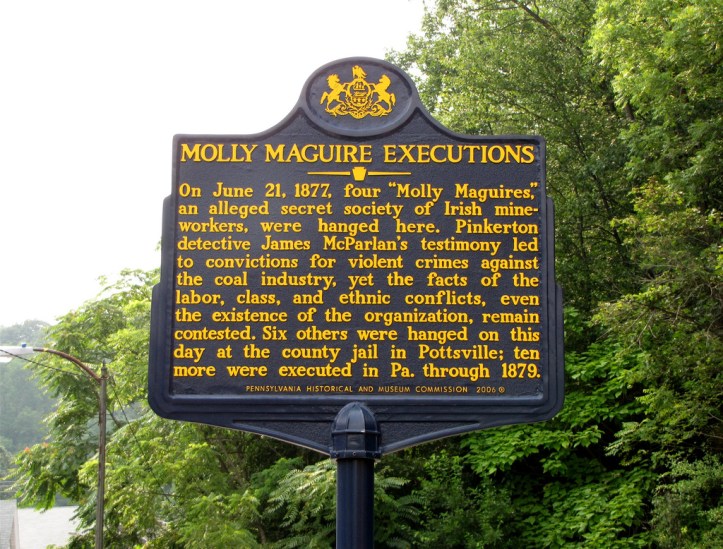

Pinkerton’s most notorious agent provocateur enterprise of early times was his destruction of so-called Molly Maguires.

The “Molly Maguires” were branch locals of the Ancient Order of Hibernians in the anthracite coal regions of Pennsylvania. Composed of Irishmen, a majority of them miners struggling for a living against a great corporation, paid the most pitiful wages, terribly oppressed in a hundred ways, the Ancient Order of Hibernians naturally became in the coal regions more of a labor union than a fraternal order.

Desperate efforts were made at the time of the Molly Maguire excitement to conceal the real nature of the organization, and to make it appear as a secret order of cut-throats, assassins and robbers purely. But Robert Pinkerton himself admitted, before the senate committee investigating the Homestead strike: These men were officers of labor organizations, and were leaders of strikes in the coal regions.”

The truth is that Allan Pinkerton was hired to “get” the Molly Maguires because they were leaders of the strikes in the coal regions. In October, 1873. F.B. Gowan, president of the Philadelphia and Reading railroad and of the Philadelphia & Reading Coal & Iron Co., engaged Pinkerton, who sent an “operative,” James McParlan, into the coal region. McParlan pursued the methods of the infamous Russian spy, Azeff, who, while in the pay of his government, plotted and directed murder after murder of government officials in order, in the end, to stamp out certain ideas dangerous to the despotism.

Became a Spy.

Within a few months McParlan was a member of the Molly Maguires, and in time he became the head of an important local. McParlan was on the job three years before he caused the arrest of his fellow “Mollies,” and it was during those three years that practically all of the assassinations of mine bosses and scabs charged against the Mollies occurred. Terence V. Powderly and other labor leaders of the time charged McParlan with plotting these murders and actually committing some of them. Indeed, Pinkerton’s own story of the affair, cunningly fabricated as it is, convicts himself and McParlan.

However, the courts and the press in the coal regions were owned by the Philadelphia & Reading railroad; Gowan himself appeared at the trials as special prosecutor; fifteen workingmen were hung by the neck until they were dead; and James McParlan went labor spying in other fields. Pinkerton figured hugely in the great railroad strikes of ’77, which were brought about by concerted and sweeping reductions of wages on the part of the roads. He put spies in the workmen’s organizations, and these men acted as agents provocateurs, inciting and perpetrating violence, which acts were seized upon as an excuse for calling out the troops.

At the same time Pinkerton undertook to furnish scab engineers and firemen to operate the trains. After the railroad strikes were ended the “National Detective Agency” was engaged for years in the “patriotic” task of putting the leaders in prison. In Allan Pinkerton’s own words: “Hundreds have been punished. Hundreds more will be punished.”

Incited to Crime.

Terence V. Powderly, president of the Knights of Labor, recites a long list of acts of violence and agent provocateur stunts, occurring during this period, which he charges against Pinkerton’s men. He tells of “Pinkertons” riding into East St. Louis on the tops of cars, firing promiscuously into strikers and citizens, killing and wounding several inoffensive persons; of Pinkerton “watchmen” putting dynamite on the tracks during the Denver & Rio Grande strike; of Pinkertons shooting strikers in the Frick coke country; of Pinkertons putting powder in a stove mold and causing an explosion during a strike of stove-makers in Chicago; of Pinkertons smearing acid on the ropes during a stone-cutters’ strike in New York; of Pinkertons wounding an old woman in Missouri by throwing a hand grenade into her window in the hope of killing her son, for whom a reward was offered, dead or alive: of Pinkertons placing dynamite on the tracks in the New York Central strike.

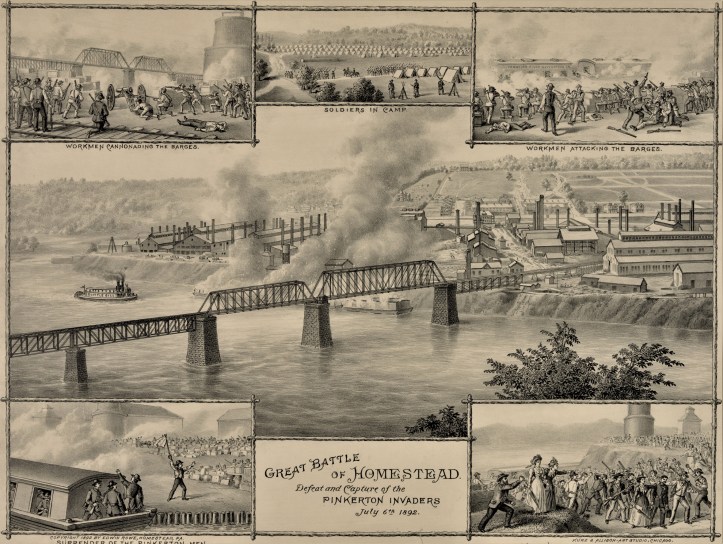

THE most spectacular episode in which the Pinkerton private army played a part occurred July 6, 1892, at Homestead, Pa., where was located at that time the largest steel plant in the United States.

The conflict between the Amalgamated Association of Steel & Iron Workers and the Carnegie Steel Company, Limited, was a direct result of the reorganization of the company and the appearance as its active head of H.C. Frick, who had already made a name for himself as a union-hater.

Frick deliberately set out to destroy the union. First he built a stockade three miles long, enclosing his entire plant. The stockade was from ten to fifteen feet high, topped with two strands of barbed wire and with port holes at intervals of twenty-five feet all the way around. Below were laid iron pipes from which hot water could be projected upon an invading force. A huge scow, moored in the Monongahela river fronting the town, was equipped with a powerful searchlight. It was by reason of these warlike preparations that the Homestead steel plant came to be known throughout the land as “Fort Frick.”

Hired a Private Army.

While this work was going on Frick arranged with the Pinkerton agency for an army of 300 men. He posted notices that beginning with July 1 the mills would be operated as a non-union plant. The workmen refused to abandon their union and July 1. not a wheel turned. Frick announced that the mills would reopen July 6, and at dawn on that date the private army, every man armed with rifles, arrived before the town in river barges.

The strikers, who had armed in anticipation of an attack, warned the gunmen not to land. A shot from one of the barges started the battle. The gunmen were finally forced to surrender. They were held prisoners until the arrival of the sheriff, who was permitted to take them away.

The senate committee which investigated the affair arrived at the following conclusion: “That the employment of the private armed guards at Homestead was unnecessary. There is no evidence to show that the slightest damage was done, or attempted to be done, to property on the part of the strikers.”

From which it might be supposed that Frick, Pinkerton and other guilty parties might have been prosecuted for a murder conspiracy.

Do not be deceived. Three guards had been killed, and seven strikers. But neither Pinkerton nor Frick nor any of their lieutenants were even arrested. On the other hand, the strikers were thrown in jail by the hundred. One hundred and sixty-seven of them were indicted for aggravated riot and conspiracy, a number of them for murder, while the entire advisory board of the union was indicted and prosecuted for treason!

Moreover, these “cases” were worked up by the Pinkertons themselves, under the protection of the state militia, which the battle had served as an excuse for calling to the scene. These private thugs, without any lawful authority, went about searching houses, insulting women, arresting men, manufacturing frame-ups upon which to “get” union men. A notable instance was the case of Hugh F. Dempsey, district master work man of the Knights of Labor, and Robert F. Beatty, who were sent to the penitentiary for seven years for conspiring to poison scabs in the Homestead mills. Six months after they went to prison Patrick Gallagher, the chief prosecuting witness, confessed in a written statement that he was a perjurer and that the entire case had been trumped-up by Pinkerton detectives.

Militia Loyal to Capital.

The militia served Frick as faithfully as any private gunmen would have done. The strikers were evicted from their homes and driven from the locality. The big steel plant opened as a non-union concern and continues to this day to operate as such. The Amalgamated Association of Steel and Iron Workers suffered a blow from which it has never recovered. Congress investigated–but did nothing. Pinkerton was exposed but continued to do business.

Frick was denounced–but he broke the strike. Government by Gunmen accomplished its purpose at Homestead.

While the Pinkerton plot to hang Moyer, Haywood and Pettibone was completely exposed by the Appeal to Reason at the time, it is not generally recognized that the Pinkerton agency was a direct instigator of the war of extermination upon the Western Federation of Miners to begin with, nor that it was largely responsible for the ruthlessness with which that was carried on.

In charge of Pinkerton’s Denver office as manager was James McParlan, the same who, thirty years before, had encompassed the destruction of the Molly Maguires. A part of a detective manager’s work is to drum up business, and in order to drum up business, McParlan represented to the mine owners of Colorado that the Western Federation of Miners was a criminal organization, far more powerful and dangerous than the Molly Maguires had ever been, that there was an inner circle, whose sole purpose was murder and arson, that all mine owners and mine officials stood in imminent peril of assassination, and mines in danger of destruction by dynamite. McParlan pointed to his record with the Molly Maguires and promised to destroy the Western Federation of Miners if given a free hand and plenty of money to do the job.

Infested the Unions.

There is no doubt whatever that some of the mine owners came to believe these tales. Others accepted the story as a feasible scheme for fighting a labor union that was threatening some of their profits. The result was that Pinkerton “operatives” swarmed in the miners’ organizations, wrote alarming and fabricated reports intended for the eyes of the mine owners, tried to incite honest miners to crime, and themselves committed crime with the purpose of sending federation men to prison. The attempted wrecking of the Florence and Cripple Creek Railroad was an instance of this sort. It was not the fault of the conspirators that scores of lives were not sacrificed in a railroad horror. Three federation men would doubtless have suffered for the crime, but H.H. McKinney, the “stool,” went back on his original confession and named the detectives, Scott and Sterling, who had promised to pay him for it. Scott and Sterling were afterwards forced to admit that, with a third operative, Charles Beckman, they had concocted a plot to induce members of the miners’ union to derail a train. It was shown that when the union men refused to derail the train, Scott, Sterling and Beckman proceeded to do it themselves.

The blowing up of the Independence depot, in which thirteen persons lost their lives, occurred only a few hours before the decision in the famous Moyer habeas corpus case, and has always been charged by union men to the mine owners, with the purpose of influencing the judges against Moyer.

Forced Sheriff to Resign.

The blood-hounds which Sheriff Robertson put on the scent led him to the house of a detective in the service of the mine owners. Presumably to shield the real murderer, a mob of mine owners forced Robertson to resign, with a rope around his neck, and appointed one of their number to fill his place, who made no effort to solve the mystery. All union miners were deported from the vicinity. Later Harry Orchard confessed to the crime, but as he also confessed to many other crimes which he could not have committed, his story was discredited. The results were entirely favorable to the mine owners. The supreme court declared Peabody’s military dictatorship legal–and all union miners were driven from that part of Colorado.

The crowning achievement in McParlan’s scheme to destroy the Western Federation of Miners was to be the hanging of the general officers of that organization. It was a Molly Maguire plot all over again. In this case the agent provocateur, spy and informer was not to be James McParlan himself, but one of his “operatives,” Harry Orchard. Ex-Governor Steunenberg was assassinated. Moyer, Haywood and Pettibone were kidnaped and taken to Idaho. McParlan stepped into the limelight and promised revelations that would hang, not only those three, but others. He also promised that if the kidnaped men succeeded in their fight to return to Colorado, he would prove their connection with a “dozen atrocious murders” which would hang them there.

“It Will Cost Their Lifes.”

“Let me tell you that the most fiendish work carried on by the Molly Maguires was but child’s play compared to the plots hatched by the officers of the Western Federation of Miners and carried into effect by their tools. It will cost Moyer, Haywood and Pettibone, and as many more, their lives,” said McParlan.

Which is, in effect, a confession of the innocence of the Molly Maguires, inasmuch as McParlan was unable to convict even a single one of the officers of the Western Federation of Miners. Harry Orchard stuck to his wildly fabricated story, but Steve Adams, who was to corroborate it, admitted that his “confession” was written by McParlan and that he signed it only when Governor Gooding threatened him with death.

Moyer, Haywood and Pettibone went free, and nothing more was heard of the “dozen atrocious murders” in Colorado.

But it was really a narrow escape. For, had Adams played out the part intended for him, Moyer, Haywood and Pettibone would undoubtedly have been hanged and McParlan would have pursued his program as to further victims.

In the face of such revelations, the Pinkerton National Detective Agency continues to do business at the old stand as a union-hunting concern. We run across it in the Holyoke, Mass. Bookbinders’ strike of several years ago. We find it operating side by side with Bergoff Brothers in the strike on the Central Railroad of New Jersey. We discover Pinkertons and Waddell-Mahon thugs slugging New York teamsters together in the spring of 1909. We learn of them exposed in Arizona in a frame-up to “get” Western Federation of Miners’ organizers. At Williamsburg, N.Y., in July, 1910, we see them firing a volley into a crowd of striking sugar workers.

It must be said, however, that the Pinkerton methods have been improved upon; and that the Pinkerton agency has been far out-stripped by men of the present day–specialists in Government by Gunmen to an extent undreamed of by the inventor of the system.

The Appeal to Reason was among the most important and widely read left papers in the United States. With a weekly run of over 550,000 copies by 1910, it remains the largest socialist paper in US history. Founded by utopian socialist and Ruskin Colony leader Julius Wayland it was published privately in Girard, Kansas from 1895 until 1922. The paper came from the Midwestern populist tradition to become the leading national voice in support of the Socialist Party of America in 1901. A ‘popular’ paper, the Appeal was Eugene Debs main literary outlet and saw writings by Upton Sinclair, Jack London, Mary “Mother” Jones, Helen Keller and many others.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/appeal-to-reason/140530-appealtoreason-w965.pdf