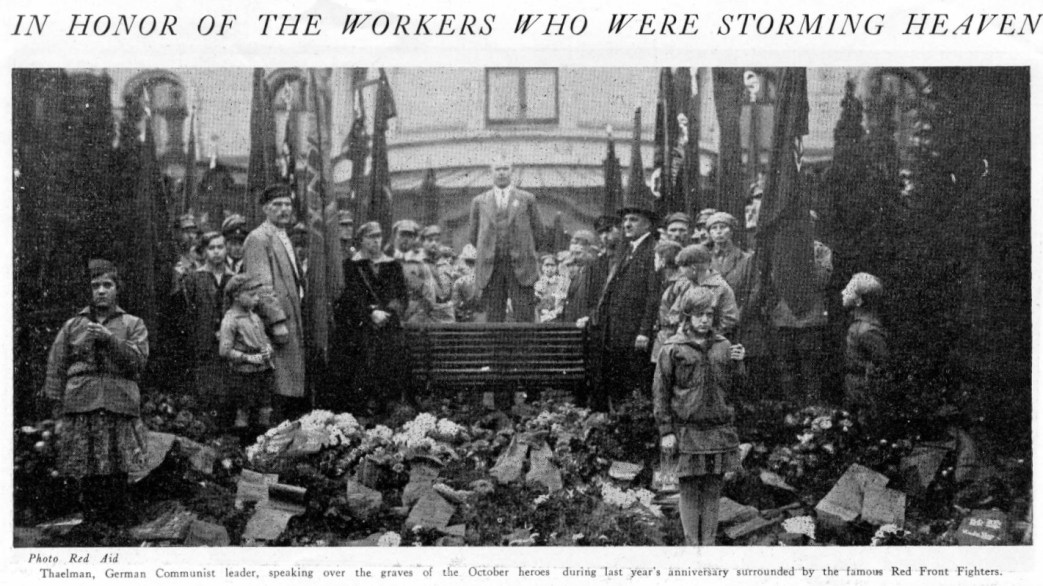

Remembering the fallen Communist barricade fighters of Hamburg on the fifth anniversary of their fight.

‘Hamburg, 1923’ by Arnold Kainer from Labor Defender. Vol. 3 No. 10. October, 1928.

HAMBURG!

The word cuts like a bolt of lightning thru the sultry atmosphere of Oct., 1923. Revolt in Hamburg! The factories in Berlin and central Germany still quiver at the word.

The burghers still run from the streets and hide themselves in their comfortable houses, no longer certain how long they will be theirs.

Revolt! Revolt! The word pounds in the brains of the half starved proletarian masses in the factories and working class quarters; the newspaper extras are torn from the hands of the sellers.

Saxony! Thuringia! Their names rose like a shout from the workers’ quarters, like an order to march–but Saxony and Thuringia remained unmoved.

But the revolt was routed, set upon and destroyed when the Voss and Blohm dock proletariats unfurled its banners. It was too late, all Germany remained quiet. Only Hamburg struggled. Huge and heroic, its barricades grew along the banks of the canals and in the workers’ quarters. With empty revolvers they ordered the police to throw up their hands in order to get weapons for the struggle. They were successful and with a handful of machine guns and rifles the wave of revolt surged out of the workers’ quarters, out of Barmbeck and Schiffbeck, towards the inner city. Thousands fell to building barricades, they waited and shouted for arms. Hundreds only were able to fight. Hamburg shouted and burst into action, but Germany, Berlin, Saxony, Thuringia remained silent.

But the reaction was watching. By motor and gun-boat, by express and armored car, they rushed from Bremen and Bremerhafen towards Red Hamburg while the senatorial bourgeoisie of the inner city armed their sons.

The struggle was thirty to one in Hamburg. Thirty thousand white guardists against bare thousand rebels. For three long days the thousand fought for every inch of their streets, for every stone in their barricades until the “sons of Ebert” were again “masters of the situation,” “order was restored,” the bank accounts were saved, and the bourgeois walked in safety on their streets again.

The “green wagons” of the police guards rolled all day long thru the streets of Hamburg, Barmbeck, Schiffbeck etc. Workers, men and women, were dragged out of their houses beaten bloody and thrown into the “green wagons” where they were slugged anew with rifle-butts, bayonets, rubber clubs until a merciful prison door closed upon them. Cowardly bourgeois walked the streets pointing out the disarmed workers with filthy denunciatory fingers: “He was one of them.” And the prisons filled until the walls threatened to burst.

“Comrade” Ebert, social democratic president of the Reich, you have conquered, your war measures can begin.

For three long years the rebels struggled against the Hamburg special acts, and for three long years the bourgeois judges hammered the memory of the October revolt in their ears. Three thousand workers guilty of high treason, an almost endless procession, came before the courts and every one of them was proud of his high treason. Every one of them stood unflinchingly by his struggle and the Party which had organized it, and every one of them went the same road,–six, eight, ten, fifteen years in the fortress.

Fuhlstbuttel and Gollnow are two fortresses in the Hamburg and Prussian province, with endlessly long buildings. Their towers stand like red brick monsters over the monotonous flatlands. Never before had their walls shut in prisoners like these. As proudly and unflinchingly as they had fought on the Hamburg barricades, as they had faced the Hamburg bourgeois judges, they now continued their struggle in the cavernous fortresses. Together with the German Red Aid, they tirelessly called the German workers to struggle for the liberation of the more than 7,000 political prisoners then filling the prisons and houses of correction of the German bourgeoisie.

With the same tireless energy, they prepared themselves, and thru their circles and self-educational groups made themselves ready for new activity in the revolutionary labor movement. By obstruction tactics and hunger strikes they had wrested to themselves a kind of self-government within the fortress. Bit by bit they won from the prison authorities a recognition of their rights as political prisoners. Their own prisoners’ council dealt with all questions involving the affairs of the imprisoned comrades and the authorities, organized circles and maintained connections with the Party.

Meanwhile considerable news, articles and appeals from the political prisoners appeared in the shop papers of the Hamburg docks and factories, while in the prison itself, their own illegal bulletin, printed monthly on monthly on a small hectograph, informed the prisoners of the events in the outside world, of the work the Red Aid, was doing for their families, etc. This did not last long before the bourgeoisie began to scream over the “Communist high schools” in Gollnow and Fuhlsbuttel; they wanted their whole vengeance. But when, early in 1925, they sought to limit the rights of the political prisoners, the prisoners in Fuhlsbuttel answered with a determined hunger strike.

“Two Hundred Hamburg October Fighters On Hunger Strike In Fuhlsbuttel,” the newspapers cried and a storm of protest broke loose in Germany. For ten days they fasted, and for ten days the workers in Voss and Blohm, the workers in Hamburg, Berlin, Leipzig, Dresden, etc. struggled for them, while the factories, the streets and the parliament of the German Republic, re-echoed with the cry: “Free the political prisoners! Free them, free them!”

Five years have gone by since the October rebels from Hamburg and Schiffbeck and Barmbeck built their barricades.

The Hamburg special acts have disappeared, the Gollnow and Fuhlsbuttel prisons stand empty. The rebels have come home to Voss and Blohm, to the harbor canals, to the docks and the workers’ quarters, and to the Party for which they struggled. They have come back stronger than before, steeled thru their struggle with the special acts and the prison authorities, clarified and developed thru the discussions and the years of study in prison.

They are in the midst of the masses again, as tireless agitators and propagandists of their revolutionary ideas, as organizers of a new October for the German proletariat. In May 1928 one hundred and twenty thousand workers greeted the men who were guilty of high treason in Hamburg in May, 1923: “comrade” Ebert, you have lost!

Long live the October struggles of the Hamburg proletariat!

Translated by Whittaker Chambers.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Not only were these among the most successful campaigns by Communists, they were among the most important of the period and the urgency and activity is duly reflected in its pages. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1928/v03n10-oct-1928-LD-ORIG.pdf