In this excerpt from a letter to Kugelmann written shortly after Lassalle’s death in a duel, Marx explains his and Engels’ break with Lassalle’s organization and paper over relations with Bismark and illusions in the Prussian state.

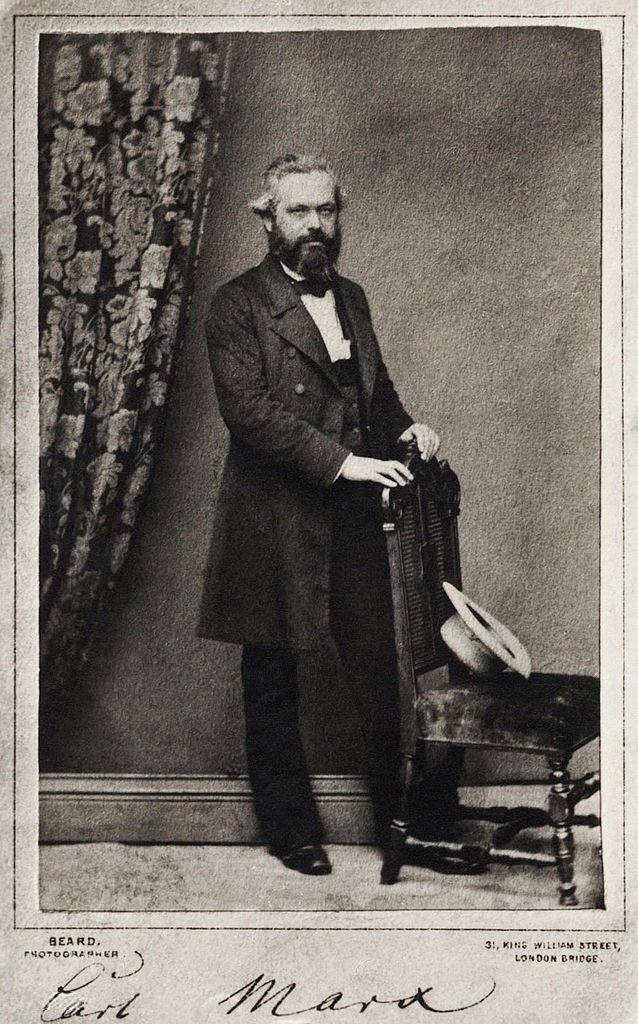

‘On Lassalle and Realpolitik’ (1865) by Karl Marx from Selected Correspondence, 1846-1895. International Publishers, New York. 1936.

London, 23 February, 1865

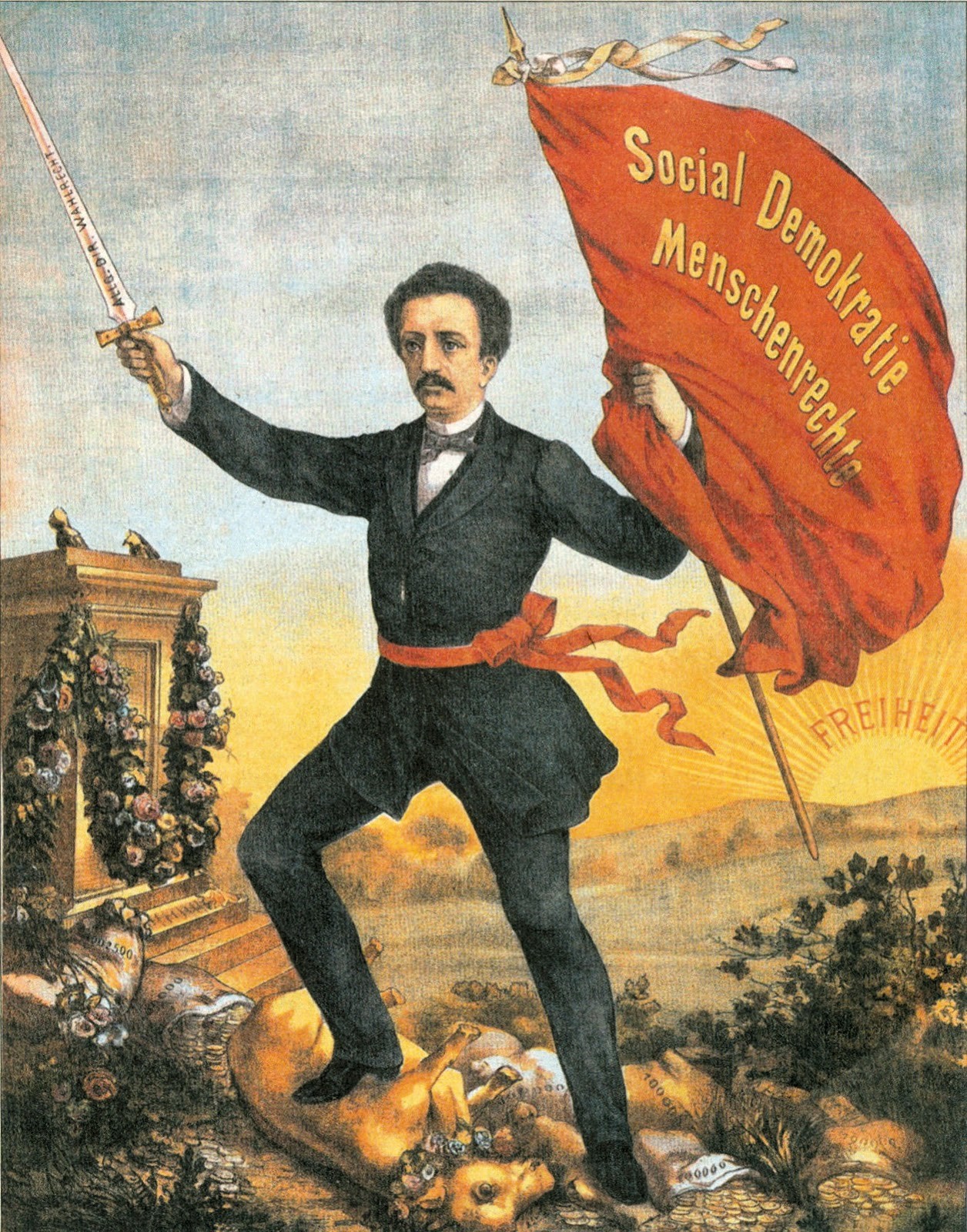

First of all I shall briefly describe my attitude to Lassalle During his agitation relations between us were suspended: (1) because of the self-flattering braggadocio to which he added the most shameless plagiarism from my writings, etc.; (2) because I condemned his political tactics; (3) because, even before he began his agitation, I fully explained and “proved” to him here in this country that direct socialist action by the “State of Prussia” was nonsense. In his letters to me (from 1848 to 1863), as in our personal encounters, he always declared himself an adherent of the party which I represent. As soon as he had convinced himself, in London (end of 1862), that he could not play his games with me, he decided to put himself forward as the “workers’” dictator against me and the old party. In spite of all that, I recognised his services as an agitator, although towards the end of his brief life even that agitation appeared to me of a more and more ambiguous character. His sudden death, old friendship, sorrowful letters from the Countess Hatzfeld, indignation over the cowardly impertinence of the bourgeois press towards one whom in his lifetime they had so greatly feared, all that induced me to publish a short statement against the wretched Blind, which did not, however, deal with the content of Lassalle’s actions (Hatzfeld sent the statement to the Nordstern).

For the same reasons, and in the hope of being able to remove elements which appeared to me dangerous, Engels and I promised to contribute to the Social-Demokrat (it has published a translation of the Address and at the editors’ request I wrote an article about Proudhon on the death of the latter); and, after Schweitzer had sent us a satisfactory Programme of his editorial work, we allowed our names to be given out as contributors. A further guarantee for us was the presence of W. Liebknecht as an unofficial member of the editorial board.

However, it soon became clear–the proofs fell into our hands–that Lassalle had in fact betrayed the party. He had entered into a formal contract with Bismarck (of course, without having in his hand any sort of guarantees). At the end of September 1864 he was to go to Hamburg and there (together with the crazy Schramm1 and the Prussian police spy Marr) force Bismarck to annex Schleswig-Holstein, that is, he was to proclaim its incorporation in the name of the “workers,” etc. In return for which Bismarck promised universal suffrage and a few socialist charlatanries. It is a pity that Lassalle could not play the comedy through to the end. The hoax would have made him look damned ridiculous and foolish, and would have put a stop for ever to all attempts of that sort.

Lassalle went astray because he was a “Realpolitiker” of the type of Herr Miquel, but cut on a larger pattern and with bigger aims. (By the bye, I had long ago seen sufficiently far through Miquel to explain his coming forward by the fact that the National Verein offered an excellent excuse for a petty Hanoverian lawyer to make his voice heard outside his own four walls by all Germany, and thus cause the enhanced “reality” of himself to react again on the Hanoverian homeland, playing the “Hanoverian Mirabeau” under Prussian protection. Just as Miquel and his present friends snatched at the “new era” inaugurated by the Prussian prince regent, in order to join the National Verein and to fasten on to the “Prussian top,” just as they developed their “civic pride” generally under Prussian protection, so Lassalle wanted to play the Marquis Posa2 of the proletariat with Philip II of Uckermark, Bismarck acting as intermediary between him and the Prussian kingdom. He only imitated the gentlemen of the National Verein; but while these invoked the Prussian “reaction” in the interests of the middle class, Lassalle shook hands with Bismarck in the interests of the proletariat. These gentlemen had greater justification than Lassalle, in so far as the bourgeois is accustomed to regard the interest immediately in front of his nose as “reality,” and as in fact this class has concluded a compromise everywhere, even with feudalism, whereas, in the very nature of the case, the working class must be sincerely revolutionary.

For a theatrically vain nature like Lassalle (who was not, however, to be bribed by paltry trash like office, a mayoralty, etc.), it was a most tempting thought: an act directly on behalf of the proletariat, and executed by Ferdinand Lassalle! He was in fact too ignorant of the real economic conditions attending such an act to be critically true to himself. The German workers, on the other hand, were too “demoralised” by the despicable “practical politics” which had induced the German bourgeoisie to tolerate the reaction of 1849-59 and the stupefying of the people, not to hail such a quack saviour, who promised to get them at one bound into the promised land.

Well, to pick up again the threads broken off above. Hardly was the Social-Demokrat founded than it became clear that old Hatzfeld wanted to execute Lassalle’s “testament.” Through Wagener (of the Kreuzzeitung) she was in touch with Bismarck. She placed the Arbeiterverein (Allgemeine Deutscher),3 the Social-Demokrat, etc., at his disposal. The annexation of Schleswig-Holstein was to be proclaimed in the Social-Demokrat, Bismarck to be recognised in general as patron, etc. The whole pretty plan was frustrated because we had Liebknecht in Berlin and on the editorial board of the Social-Demokrat. Although Engels and I were not pleased with the editing of the paper, with its lick-spittle cult of Lassalle, its occasional coquetting with Bismarck, etc., it was of course more important not to break publicly with the paper for the time being, in order to thwart old Hatzfeld’s intrigues and the complete compromising of the workers’ party. We therefore made bonne mine a mauvais jeu [put a good face on it], although privately we were always writing to the Social-Demokrat that Bismarck must be opposed just as much as the Progressives. We even put up with the intrigues of that affected coxcomb Bernhard Becker–who takes the importance conferred upon him in Lassalle’s testament quite seriously–against the International Workingmen’s Association.

Meanwhile Herr Schweitzer’s articles in the Social-Demokrat became more and more Bismarckian. I had written to him earlier, that the Progressives could be intimidated on the coalition question, but that the Prussian government would never concede the complete abolition of the Combination Laws, because that would involve making a breach in the bureaucracy, would give the workers adult status, would shatter the Gesindeordnung, abolish the flogging regime of the aristocracy in the countryside, etc., etc., which Bismarck would never allow, which was altogether incompatible with the Prussian bureaucratic state. I added that if the Chamber rejected the Combination Laws, the government would have recourse to phrases (such phrases, for example, as that the social question demanded “more thorough-going” measures, etc.) in order to retain them. All this proved to be correct. And what did Herr von Schweitzer do? He wrote an article for Bismarck and saved all his heroics for such infiniment petits [infinitely small people] as Schulze, Faucher, etc.

I think that Schweitzer and Co. have honest intentions, but they are “Realpolitiker.” They want to accommodate themselves to existing circumstances and not to surrender this privilege of “real politics” to the exclusive use of Herr Miquel and Co. (The latter seem to want to keep for themselves the right of intermixture with the Prussian government.) They know that the workers’ press and the workers’ movement in Prussia (and therefore in the rest of Germany) exist solely par la grace de la police [by the grace of the police]. So they want to take the circumstances as they are, and not irritate the government, just like our “republican” “real politicians,” who are willing to “put up with” a Hohenzollern emperor.

Since I am not a “Realpolitiker,” I have found it necessary to sever all connection with the Social-Demokrat in a public declaration signed by myself and Engels (which you will probably see soon in one paper or another). You will understand at the same time why at the present moment I can do nothing in Prussia. The government there has refused point blank to re-naturalise me as a Prussian citizen. I should only be allowed to agitate there in a form acceptable to Herr v. Bismarck.

I prefer a hundred times over my agitation here through the International Association. Its influence on the English proletariat is direct and of the greatest importance. We are making a stir here now on the General Suffrage Question, which of course has a significance here quite different from what it has in Prussia.

On the whole the progress of this “Association” is beyond all expectation, here, in Paris, in Belgium, Switzerland and Italy. Only in Germany, of course, Lassalle’s successors oppose me, in the first place, because they are frantically afraid of losing their importance, and, secondly, because they are aware of my avowed opposition to what the Germans call “Realpolitik.” (It is this sort of reality which places Germany so far behind all civilised countries.)

1. Rudolf Schramm.

2. Marquis Posa, the hero of a play by Schiller; he was convinced that he could persuade the tyrant Philip II of the justice of his cause.

3. General Association of German Workers.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of later edition of book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.227457/2015.227457.Selected-Correspondence.pdf