We are lucky that for the British General Strike, of which this year is the centenary, the inimitable lead columnist for the Daily Worker, Irish-born Thomas J. O’Flaherty, was present and recorded events for posterity. Part of a series of articles he would produce over the months that followed, O’Flaherty walks through London on May 4, 1926.

‘New Days in Old England: The Big Battle Opens’ by T.J. O’Flaherty from The Daily Workers Magazine. Vol. 3 N0. 147. July 3, 1926.

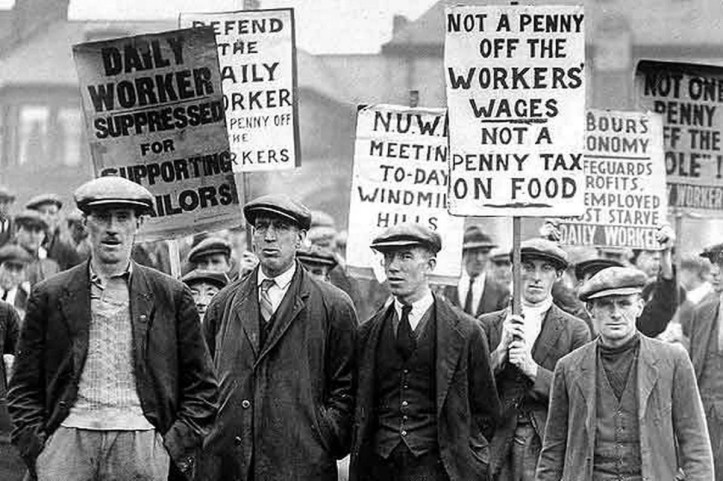

THERE were two British governments sitting in London on the morning of May 4, when the first line of defense of the army of labor was thrown into the struggle to defend the miners, in what developed to be the greatest general strike in human history from the point of view of forces arrayed, one against the other, though it ended in a debacle hardly without parallel in the records of the labor movement of any country.

At Downing street the executive committee of the capitalist class, which was solidly behind the coal owners sat and acted with vigor. They had no illusions about the challenge to the government involved in the general strike, though being quite well aware that the leaders of the General Council had no more ambition to overthrow the government than had the prince of Wales, who had returned from a continental watering place to do his duty at the home front as his good friends on the capitalist press told us. He flew home in an airplane and was not heard of any more until after the strike was over, when the papers announced that he had to go grouse hunting in Scotland in order to recuperate after his arduous toil during the crisis.

Eccleston Square was the seat of the industrial government which did not realize it was a government. Neither did it want to. Here was quartered the high command of the labor forces, with Ernest Bevin, the “Dockers’ K.C.” general in command

The statue of Lord Nelson, in Trafalgar Square, looked down on a group of buildings in which were housed as worried a set of British officials as ever presided over the destinies of the empire. Not since the Spanish armada threatened the “tight little isle” in the days of the “Virgin Queen” were there so many evil forebodings floating thru the air of Whitehall.

All the capitalist papers, with the exception of the Daily Mail and a few others, were on the streets screeching like deceived prostitutes. Yet they knew what they were talking about. There was no division here. Most of them had words of praise for J.H. Thomas.

Pictures showed Mr. Thomas shedding tears all over the town. He was their man.

Motorcycles with message-bearers dashed out of Whitehall to all parts of the country. The government knew it was at war, and it did not know how long it would be able to depend on the telegraph.

Similar sights could be witnessed at Eccleston Square. Here is an excerpt from an announcement that appeared on May 3 in the Daily Herald:

“The T.U.C. appeals to all friends and supporters who have motor cars to place them and their own services at the disposal of the Movement in order to maintain a complete chain of communication between district and district.” This also looked as if the T.U.C. knew it was at war.

There were plenty of motorcycles, with engines running and riders in the saddle, waiting at all trade union headquarters. They also rushed madly to all parts of England, Scotland and Wales with dispatches. The government dared not interfere.

As a matter of fact, the government was as weak as a cat during the first days of the strike. The legend “By Permission of the T.U.C.” carried more weight in many parts of England than “On His Majesty’s Service.”

***

THE Welsh chambermaid in the hotel where I stayed was humming a song as she worked. I suspected the language was Welsh, and so it was.

Being curious, I inquired what it was all about, and she told me that the song was in praise of the prince of Wales.

Her three brothers and father were on strike and she was certain they would fight to win.

“What do they do when they are on strike?” I asked.

“They go out on the hills and kill sheep,” she replied. “Sure, they won’t be hungry as long as there is anything to eat.

“But what about the prince? Surely he has no interest in the miners.”

“Oh, yes, he loves them. You know I went down to Hyde Park last Sunday to hear him speak. I often go there to hear the Red Flag and the Welsh singers. There is a lot of singing in Hyde Park. There is Irish singing there, too, but the Welsh always beat the Irish singing.”

“Did the prince speak last Sunday?”

“No,” she replied, rather sorrowfully.

“That’s that,” said I to myself, as went out to see what I could see.

Every conceivable kind of vehicle was in the streets. The congestion was almost perfect. The taxi drivers were not yet out, but a pair of cornless feet was the quickest means of locomotion.

I went into a barber shop on Fleet street for a shave. This was on the first day of the strike. A jovial fellow bearing all the scars of a journalist (mostly on his nose) entered and remarked to the barber: “Well, I see that you are not on strike yet!” “Not yet,” replied the barber. “But who knows? Next week, perhaps you may be walking around with a pair of whiskers that would make any one of the Smith Brothers turn green with envy. Are you going to fight for your king and country this time?”

“Like hell I am. I did that once and once was enough. I am for labor in this scrap. The holding up of the Daily Mail was the best thing that was ever done in this country.”

It was not difficult to run into that kind of sentiment around town, particularly where workers of any category of labor congregated.

There was a different atmosphere on the Strand and the nearer one got to Whitehall the tougher it got. This is where the building that houses the Morning Post plant is located. The Post is the leading organ of British fascism and it was this plant that the government “commandeered” in order to be in a position to issue the “British Gazette.” It was rumored that the Daily Mail people were quite angry with the government because the Carmelite House plant was not selected.

The Post got considerable advertising out of the use of its plant and no doubt a bonus in cash besides.

Winston Churchill came as near being a dictator during the strike as he and his chief aids would publicly admit. He wrote the articles in the Gazette, signed “By a Cabinet Minister.”

Churchill is extremely unpopular in England with most sections of the population, the fascists alone, perhaps, excepted. But he is aggressive and an extreme labor hater. He was the man to give the trade unions the “whiff of grape shot.” And he was perfectly ready to draw blood.

Churchill drove up to the triangular Post building about midnight on May 3. About five hundred scowling trade unionists were watching the clumsy efforts of a few dozen scabs trying to unload print paper off a truck. Little by little the hum of conversation increased. Most of the on-lookers were printers. Police were stationed at short distances from each other around the square. I spoke to a little man at my side and made an uncomplimentary remark on the skill of the blacklegs. A policeman cocked his ear and walked over to an inspector who stood in the middle of the square.

The latter immediately called his force together and gave them orders to disperse the crowd.

On the following evening I accompanied Charles Ashleigh to a printers’ meeting somewhere around Fleet street, and the first person I laid eyes on was the worker I accosted on the previous evening. He was a member of Natsopa, the organization that stopped the Daily Mail.

***

OPPOSITE the Bank of England, right in the heart of the city a boy was selling the British Worker. Nobody particularly cared what kind of a paper it was, but they grabbed it. It was not the most fertile ground to drop the labor seed on, but the newsboy did not care as long as he was getting the coppers.

A typical burlesque stage Englishman emerged from one of the counting houses and dashed for the newsboy. “Paper,” he asked. He was handed a British Worker. Gazing at it rather abstractedly, he passed the penny to the newsboy with a slow motion movement. When he recovered his senses he muttered audibly. “By George! A labor paper.” Yes, the sacred precincts of the city was being invaded by the proletariat.

On the Strand opposite Charing Cross Station a plump lady was sampling the wares of a mushroom newsboy (his boyhood days were only a memory). He had quite a collection of sheets issued by enterprising merchants. A very effective method of advertising. All the news, if such it may be termed, was from the British Broadcasting Company, a government monopoly, and the most lying institution that ever used the air.

I asked the old news vendor for a copy of the British Gazette. He went to hunt for a copy. “Stirring days,” I remarked to the lady. “The country is pretty well tied up.” She burst into fury. “These labor leaders should be shot,” she said. “The government should call out the Grenadier Guards and give the cattle a lesson.”

“Don’t you think the government broke off negotiations rather precipitately?” I observed. The lady grew purple. “Negotiate with that rabble!” she snorted. Then some more suggestions as to the use of gunpowder.

“They must be taught to know their place,” was her parting shot.

A newsboy in front of the post office at Trafalgar Square did not have a copy of the British Gazette, but he promised to have a copy for me about 12 noon. When I returned he handed me a British Worker. I asked for a Chicago Tribune, Paris edition. This was the third day of the strike. Nothing doing. Scotland Yard would not allow him to carry the Trib. Why?

On the previous day he was shouting his wares, and a Tory M.P. who was passing by thought the contents of the paper as heralded by the young lad was favorable to the workers.

Lloyd George said something in behalf of the miners and blamed the government for breaking off negotiations.

“Free speech” did not work in England any more. The M.P. called a bobby and asked him to arrest the newsboy on the ground that he was inciting the public. The constable looked at the paper and said that the stories justified the lad, so he could not arrest him. The Tory was far from satisfied, so he went down to Scotland Yard and returned with an Inspector. The latter warned the newsboy to be careful in the future and told him that he could not secure any more Tribunes until the strike was over. He kept his word.

The Saturday Supplement, later changed to a Sunday Supplement, of the Daily Worker was a place for longer articles with debate, international focus, literature, and documents presented. The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1926/1926-ny/v03-n147-supplement-jul-03-1926-DW-LOC.pdf