Friedrich Wolf, German playwright exiled from Nazi Germany, brings the learned outsider’s perspective to this valuable survey of New York’s radical theater during its mid-30s height.

‘New York Theatre Front: 1935’ by Friedrich Wolf from International Literature. No. 8. 1935.

“How do you like New York, Doctor?” I was asked at least ten times a day even by intelligent people, and during my seven weeks’ stay I had to answer some five hundred times, “Thank you, damn it, yes and no!” And yet I fully understand the New Yorkers’ pride in their city; I too admire this athletic metropolis with its clean-cut giant buildings, bare of any ornament. But blood rushes to my head when I see how a poor Negro peddler is brought before the judge in a night court by a Negro detective. It is admirable that one can live there for years without the police wanting to know my name or the name of my grandfather—or that on Sunday hundreds of thousands lie on the grass in huge Central Park right in the middle of the city. But I was astonished to see Negro and white, rigidly separated along color lines, staring at me from their cage-like cells in the model women’s prison in New York, although even Hitler hasn’t yet introduced race differentiation, at least in the jails and concentration camps. Frightful the flood of yellow weeklies and movie magazines—astonishing and welcome the fact of the New Masses and the New Theatre. Nowhere does one see the relativeness and the unity of contradictions as clearly as in the centre of highly developed capitalism.

Particularly along the theatre front.

Everything takes place here in the most concentrated form: the tempo of life, eating, business, the concentration of the skyscrapers on the tiny island of Manhattan; and the twenty to thirty big theatres and movie palaces are likewise squeezed together into the four or five blocks along Broadway along Times Square. Even in theme, style, and genre a single winter season—1934-35—comprises everything we went through in a period of ten to fifteen years on the German theatre front. I saw twelve different plays in the theatre district, which can be covered on foot in less than twenty minutes: star plays of the boulevard hit or London comedy of manners type, costume plays like those put on by the Rotter theatres in Berlin, naturalist milieu plays, plays of social criticism a la Ibsen, Strindbergian psychoanalysis—and then right off Broadway a Proletcult play admirably staged by the collective of the Group Theatre. Finally down on Fourteenth Street the revolutionary drama Black Pit played by the actors of the Theatre Union to enthusiastic audiences of workers, intellectuals and middle-class groups. This spiritual Wild West of the New York theatre, this multiplicity and anarchy, is no “esthetic” matter high up in the clouds. In its structure and pace it is rather the exact reflection of the tempo of the crisis and the economic anarchy of this continent in which there are piled high inconceivable quantities of capital, wealth, and misery.

The first thing we Europeans must do in New York is to forget the concept of the “Theatre,” of the theatre as an institution, possessing a tradition, such as the Lessing Theatre or the Deutsche Theatre in Berlin, the Comedié Francaise, the Theatre Sarah Bernhardt, not to mention the Meyerhold, Tairov or Vakhtangov Theatres. Here the producer, that is the entrepreneur, who provides the money for a given play and hires the director is the “theatre”. Noted producers work in one theatre today, another tomorrow, today with this director, tomorrow with another; the stars change even in the production of a single play. The program for Tobacco Road—the play of the Southern farmer, excellently staged by the young director Brown—informs you that the leading actor was changed three times in a single year, because the leading man was snatched up by Hollywood every time. That is—or was up to now—the best recommendation for a play, for the director, for the star.

It was an act of revolutionary courage three years ago when young Left actors formed a collective and started playing as the ensemble of the Group Theatre…and they have been able to keep going these three years with increasing success. But the “Group” did not remain an isolated phenomenon Three years ago the Theatre Union started with a clear-cut class-conscious program, with another acting company. The Theatre Union group has gone through more than one ordeal by fire. Its chief contribution was the organization of its mass audiences, giving them high-class performances at the lowest prices and registering one success after another during these first three years of struggle. The third ensemble that was formed in defiance of all the commercial traditions of the New York theatre is the Artef Theatre, a Jewish theatre that began with worker-actors, who today, however, have quite attained the standard of good professional acting. Today these Artef actors still work in shops during the day, playing at night without salary. The Theater of Action has also just produced its first full-length play and is establishing itself as a permanent acting company.

This break with the forms of the existing commercial theatre took place at a tempestuous rate, and only within the last two or three years. Bourgeois critics told me that the next theatre winter season would be even more “Left”; most of them are not indignant about it because they are already “fed up” with the present day theatre. Equally symptomatic is the work of the film studios. “Social themes” are more and more in demand. One of the most highly paid Hollywood actors is Paul Muni, who essayed the role of an anarchistic miner after his excellent performance in I Was a Fugitive from a Chain Gang. Phantom President and 42nd Street were in the same genre. True enough, the posing of the problem and its solution are false but the theme simply cannot be evaded today.

The Star Play: Katharine Cornell, Elizabeth Bergner, Kathrin Maren, Tallulah Bankhead

When the first night of Flowers of the Forest with Katherine Cornell was advertised, I was told I simply had to see ‘America’s greatest actress,” but that it would be difficult to get tickets. We went to the premiere at six in the evening…the theatre was hardly half full. My friends said that would have been inconceivable a few years ago; when Cornell played, she could have recited the ABC and the public would have come to see her. What has happened in these few years? She still wears wonderful gowns and has a “magical” stage presence. Can the public have grown more critical? Can it be that it no longer wants to see these hypocritical, moth-eaten plays—even when they dabble in saccharine pacifism like Flowers of the Forest? Katharine Cornell, who in the past played to packed houses for months now announces that she is leaving for Paris after the play had been on for only three weeks, and not even going to play Shaw’s Candida.

I saw Elizabeth Bergner in Escape Me Never, a sort of English La Boheme. The first scenes, in which she played the role of an eighteen-year-old in short skirts, with socks on her ephebic legs, were well suited to her. But later on, when she had to play the great lover, she was through. And when she had to hold her child in her arms in the role of a mother, the “make believe” became so unendurable that not only I but ten others started for the exits. But strange to say, two ushers blocked the exit doors, because “Frau Bergner does not want people to leave.” This star play is also beyond discussion in point of content and form. Here too the public turned away from Bergner, its favorite, because of the miserable play and her falsetto tones. The public doesn’t let itself be fooled so easily any more. If it is to be fooled; it demands plays for its stars at least, such as Lady of the Camelias, A Doll’s House, Hedda Gabbler or Saint Joan.

A typical example is furnished by the endeavor to star a little Viennese actress Kathrin Maren, in an empty bit of trumpery The Day To Night (The Trip to Pressburg). The endeavor was a one-hundred per cent failure despite millionaire “angels”; the play closed after a two-week run. The foundation of the commercial theatre is beginning to totter.

Something Gay, with the celebrated Tallulah Bankhead, was also not very gay, as a critic remarked, because of the poor play. Today stars alone aren’t enough; the actress’ road “through the bed” no longer leads to success. Today the public is an active factor—it demands an answer to certain questions that trouble it.

The Negro Problem: Green Pastures

This Negro play had been running uninterruptedly for five years; in 1930 it received the Pulitzer prize. The program begins by saying that it took in 17,200 dollars, even in the last hot week of August 1931, but unfortunately it is not a good play none the less. Largely because it is a false play, because it shows Negro life as certain whites imagine it or would like to think it is. All the actors in this play are Negroes; their acting is often excellent; they sing their spirituals wonderfully well, and yet the play is thoroughly false. It is false all the way down to the foundation, from the problem it poses to the treatment of the theme. The play is really a Biblia pauperum, a set of Bible pictures like those printed in the Middle Ages for illiterates. All the history of the world and of humanity down to our day is treated in biblical style; the problem is posed thus: has humanity grown “better” during this period? Must it not return to the innocence of paradise, after having eaten too much of the tree of knowledge? The (reactionary) answer is clear cut: we see in the play how the ten thousand years of humanity’s development have not helped, but have only harmed the human soul, how man only becomes “worse,” more dissatisfied, more a beast of prey, with too much knowledge, technique, cities, and culture. We are told there is only one salvation: return to the “Green Pastures” of Paradise.

The play, with its thirty scenes, is definitely “epic theatre,” a didactic play of the first order. To a certain extent it emphasizes this by beginning the first scene in Sunday school. Negro children, learning the story of Creation, ask their Negro teacher embarrassing questions, which he is finally unable to answer. Then “the Lord,” or as he is called in Negro dialect “The Lawd,” takes a hand in person—as God. In the second scene Heaven is in a state of turmoil—should a new star, i.e., the Earth, be created or not—and now “The Lawd” enters with a fat “ten-cent cigar” in his mouth, provoking tremendous enthusiasm among the male angels and smiles among the spectators. There you have it: even in Heaven the ideals of these poor devils, the Negroes, picture a ten-cent cigar as the compass, the symbol of divine perfection. “So that is the phantasy world of these Negroes, these children who still live as illiterates in childhood dreams,” is what the white spectator must feel. They must feel themselves to be a higher, ruling race when they see the Negroes in the Green Pastures. This is the clear-cut tendency of this Negro play written by Marc Connelly, a white; this is also one of the reasons for its success. “Look at these dumb Negroes—how they still imagine the world to be! Are we to let ourselves be placed on an equal footing with them? The numerous witty parodies, the anachronisms (“The Lawd” sitting in his modern office), and the interesting production might deceive many spectators as to the value and character of the play. But many Negroes told me that this play is a libel on the Negro, a play that tries to make the gulf between the Negro and white still deeper. No, millions of American Negroes are no longer children!

Tobacco Road: Farmer Distress in the South

Neither the American film nor the American theatre can evade the major social problems, such as the Negro question and the farmer problem, in their selection of themes. In The Green Pastures, the Negro question is dealt with in a thoroughly class manner from the standpoint of the ruling class, as a didactic play.

In Tobacco Road the tendency breaks through, but unpremeditatedly in an opposite direction. This play, “situated on a tobacco road in the back country of Georgia,” was adapted by Jack Kirkland from the novel of the same name by Erskine Caldwell. With uncompromising naturalism down to the last detail it pictures the dreary decay of a poor farmer’s family, slowly degenerating as a result of hunger, drought, exploitation by speculators and nymphomaniac cultists, as a result of all sorts of delusions, diseases and impotence. The value of the play lies in the excellent, sober production by the director Brown. He has not only caught the milieu and the atmosphere of this ghost-like rainless area of the South, almost cut off from the civilized world, down to the dry air, the floury brown sand, the dried out bodies, and the so much more wildly flaming lusts. What is more important: he shows how man is the cruelest force of nature—these carefully groomed gentlemen, these respectable landlords and speculators, who after having sucked the small farmer dry through high rents take from him the last things he has, his bit of earth to which he clings with animal terror. Jeeter Lester, this poor Georgia farmer, is the last one to die—after all the others are either dead or have fled—letting a handful of the dry brown sand run through his fingers.

This grim play of farm distress in “God’s own country’, this hopeless naturalistic play without a happy ending played in one of Broadway’s commercial theatres, became the biggest hit of last season and has now been running without interruption for two years. Why? Some seek a simple explanation for the success in the play’s strongly erotic scenes; but all this eroticism ends in despair, death, flight, destruction. The value of the play and, above all, of the production, lies in its anatomical objectivity, in its content of truth. This fills the public with shivers; it feels that it is not being “hot air” but a portion of reality—a tiny incomplete portion yet reality none the less. A section of the world is shown true to life, naturalistically, staring at nothingness, poverty as a phenomenon of nature.

But this play wholly lacks perspective, a way out, the conscious man who is able to change the world. And yet big farmer revolts have taken place in the Southern States precisely during the last three years, and mere possession of the Daily Worker is punishable by hard labor and the chain gang. A realistic play on the South would have to show this side as well; the endeavor to shake off the chains and poverty.

The naturalistic play says: “Well, well, that’s what the world is like, that’s what it was and that’s how it will remain!” The realistic play shows or implies the process of development: “That’s what this bit of the world is like today, but this today already bears within it the germ and the prerequisites of tomorrow; this is what the world is like, but we shall change it!”

‘The Children’s Hour: The Problem of Bourgeois Morality, “Justice,” “Personality”

First of all, brilliant staging by the best, clearest, most precise New York director, Herman Shumlin. Of all the plays I saw during these seven weeks in New York, I felt the firm hand of the director in only four: The Children’s Hour, Tobacco Road, Awake and Sing! and Recruits.

The Children’s Hour deals with a pathological boundary-line case in a fifteen-year-old girl, a blend of pseudolog phantastica and Friihlings-Erwachen. Overhasty punishment by a young teacher in a boarding school gives rise to a desire for revenge and phantastic webs of lies in the sexually excited child, turning into false charges against two teachers and the attending physician. The influential grandmother to whom the girl has fled believes the lies. Her morality and her “sense of justice” are profoundly injured and she forces the institute to close. The two young women teachers have nothing to look forward to; one of them commits suicide after confessing in the last act to the other that the girl’s testimony is insane, if for no other reason than that she has lesbian feelings for her.

The theme of the play is that of Strindberg’s plays and of the early works of Wedekind, but Strindberg’s and Wedekind’s works are taller by two heads than this psychoanalytical essay by Lillian Hellmann, the author. Here, as in Tobacco Road, the value and success of the play lay in the production and in the eagerness of the public starved on a fare of the shallowest Broadway plays. Here too, the hypocrisy, rottenness, crumbling, helplessness of present day society were demonstrated in a tiny “link,” thanks to the director’s magic art…perhaps without his even intending to do so. The masterly drawing of the corrupt, weak and helpless types of this stratum of society, worm-eaten—”Qvermoulu” is what Alvin says in Ibsen’s Ghosts—itself becomes first-class social criticism. Again we get what Karl Marx pointed out in the great realist Balzac: his portrayal of the social class to which he himself belonged and which he wanted to interpret becomes, almost against his will, the damning indictment of his own class. Or as Lenin once said: there are portrayals in which “things begin to talk their own language”…against the author’s intentions. In spite of the weakness of the play and the eccentricity of the theme, The Children’s Hour is one of the most valuable productions I saw in New York.

Recruits, or So It Has Been, by A. Resnick, is, as the subtitle indicates, a “historical” play, a play depicting the class fronts in a little Jewish village in Poland in 1827. The theme is the compulsory recruiting of young Jewish workers. The term of service was…twenty-five years. They were sent to the most distant garrisons of Russia; never did one of these recruits ever see his home village again. The plot of this play is the love story of Nachman the poor young journeyman tailor, and Frumele, the daughter of Pinches, the rich man. This plot is based on the old reliable theatre foundation of happy and unhappy love, with moonlight sonatas, balcony scenes, window rendezvous at night, expulsion of the “adulterers,” with false rendezvous and love letters as love traps. All this is very nice but unimportant. What is important however, in this naturalist milieu play is the sketching of the environment, the minor figures, the social background against which the action takes place. Even in this little village, cutting right through this “homogeneous race,” we see class lines. We see Chief Rabbi Motele doing a profitable business with his blessings, the poor Jewish artisans breaking into the Synhedrin of the well-to-do philistines to seek protection—in vain—from the tsar’s recruiting officers, and finally Aaron Kluger, the money dynast of the village, directly deceiving poor Nachman and delivering him to the tsar’s henchmen.

These episodic figures, this precise portrayal of the milieu, is the best thing in this excellent production and—like Tobacco Road and the Children’s Hour—it is due to the director Benno Schneider. He has learned much from Stanislavski and Vakhtangov; the production has atmosphere and background; the types and characters are drawn with considerable plastic effect. The danger inherent in this production is the over-precise outlining of detail, the director’s love for this Jewish, musical milieu. Here the clear dramatic line suffers—the play threatens to fall apart into little episodes. But that is the danger inherent in all Jewish folklore. Schneider must test his strength and talent on modern material with taut action. Lyricism is a perilous blandishment for him and for the highly talented Artef acting company.

Awake and Sing: Decay of the American Petty Bourgeoisie

Awake and Sing by Clifford Odets—a play by an actor in the Group Theatre—was a great triumph for the “Group.” In dozens of penetrating and well-drawn episodes this play shows the undermining, the rotting away, the “living lie” of this petty-bourgeois family in the Bronx. If this accurate portrayal of environment were all this play has, it would be a throwback to the naturalism and petty-bourgeois social criticism of Ibsen and Shaw. But in Awake and Sing there are two figures who stand with one foot outside the declining middle class, their faces turned to the arising working class and the doctrines of Karl Marx. These two—the grandfather and the grandchild give the mosaic of many episodes a purpose, a point, a perspective. Whereas the ably written naturalistic plays like Tobacco Road and The Children’s Hour fill the spectator with the tired echo: “Well, well, that’s life!” Awake and Sing begins to activize the audience: “Out of this decay, lie, self deception! Cost what it may, out towards a new clarity, a new purpose, a new life!” Of course, the old man who plays Caruso records at night, reads Karl Marx, and is full of anarchist revolutionary romanticism, is a scurrilous figure, resembling Ulrik Brendel in Ibsen’s Rosmersholm; but after the old man dies the young grandson takes over his books, with a clearer perception. It is he who gives the play and also the spectators—a definite direction. And because the audience at last feels itself being led again, deliberately led, this play excites it, activizes it, awakens it to stormy applause.

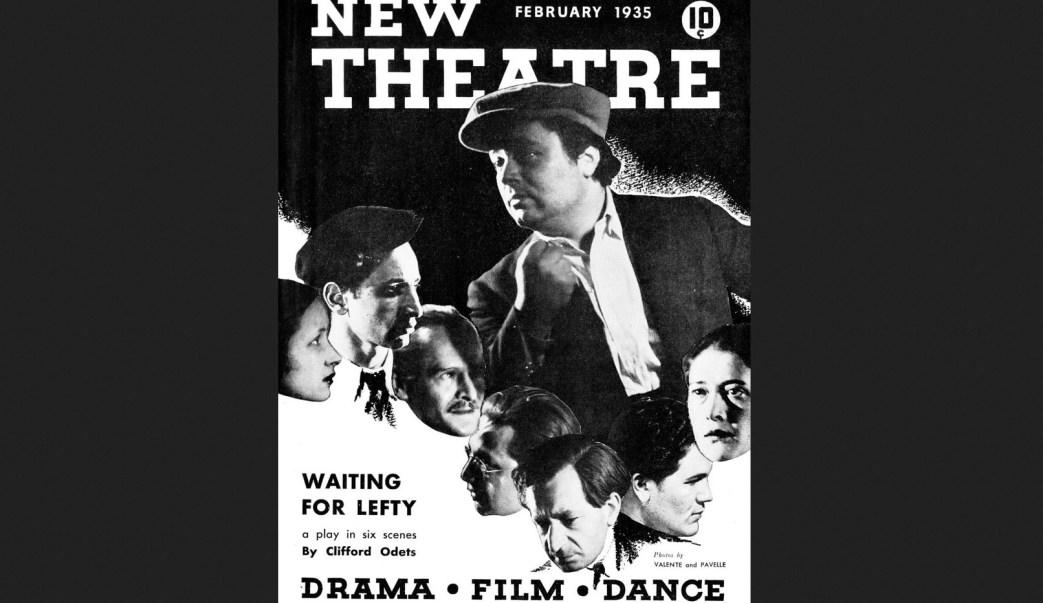

Waiting for Lefty—Till the Day I Die

A strike play and an anti-Nazi play. Both of these are occasion plays. Waiting for Lefty was originally written for only one Sunday evening performance last January, a benefit performance for the striking taxi drivers of New York and for the family of the murdered strike leader “Lefty”. The program of the Broadway theatre (the Longacre Theatre) in which this revolutionary agit-prop play was produced contains the following note by the “Group”: “To the author’s and actors’ surprise the performance ended with an ovation; the audience remained standing after the curtain fell, clapping, stamping their feet, highly excited.” Later performances met with similar success. The “Group” wanted to test this success before a working-class public by a production on Broadway; but Waiting for Lefty was only a short one-act play that could not fill an evening. So Clifford Odets had to decide to write a second play, post haste, similar in style and content to the first that could fill a regular theatre evening of two hours on Broadway together with Waiting for Lefty. This second play was Till the Day I Die; he wrote it in five days and nights, basing it on a letter from a Communist Party worker in Hitler Germany printed in the New Masses.

Only when we know these antecedents can we make a correct appraisal of these two plays written and conceived as agit-prop material. They were written by the same young actor Clifford Odets who wrote Awake and Sing for his “Group”. These two one-act plays were also performed by the “Group” acting company, so that the twenty-six actors of this Left collective are now playing their plays, the plays of their own author and actor Odets, in two big Broadway theatres every evening—the first time this has happened in New York theatre history.

Waiting for Lefty deals with a meeting during the 1934 taxi strike in New York. According to the excellent pattern of our former agit-prop plays, the stage is the platform and the audience the strike meeting with hecklers, speakers and opposing speakers…everything that we have seen in at least as good productions in a dozen similar French, German, Russian (Proletcult) agit-prop plays. Nothing out of the ordinary for a European spectator; on the contrary, Brecht’s Massnahme and Mother and Wangenheim’s Mausefalle are on a wider and higher plane artistically and ideologically. But for the American spectator, the treatment of proletarian problems on the professional stage is such a sensational surprise, the agit-prop form displayed by a disciplined company is such a novel impression, in fact a discovery, that he enthusiastically hails the “new” form and the exciting content. A discoverer’s joy for the public and a surprise victory for the author and the collective! A tremendously important and merited success! But it must not deceive us—and least of all the Group Theatre—into believing that the next successes can be achieved with the factor of surprise. They will have to be gained by a profounder posing of the problem and handling of the theme.

This applies above all to Till the Day I Die. I have already pointed out that criticism of these two one-act plays must make allowances for how these agit-prop plays arose. The author and the company were themselves completely astounded by the unexpected success of the first one-act piece. In order to turn this success to account, the author had to write the second one-act play in five days “like a machine gun.” Unfortunately he chose a subject he did not know and could not know: Hitler Germany. This most difficult theme–written in five days, from a letter—for a one-act play! I am convinced that with Odets’ talent, he would have handled a theme from the American labor movement of today just as successfully as Waiting for Lefty. In Till The Day I Die not a single figure and scarcely a single situation is really correctly drawn; such Storm Troopers and Nazi commissars exist really only in certain comic magazines. If the Storm Troopers had actually been such fools and their officers such noblemen or stupid rascals, one would be justified in wondering how these Nazis ever triumphed. Unfortunately these German Nazis were and are much more complicated, both in their own structure and in their struggle against the workers. And a tested illegal fighter such as Ernst Taussig is never liquidated by the Party unit merely on suspicion. Here the stool pigeon problem enters, which does not exist to this extent in Europe.

Despite these serious objections to Odets’ anti-Nazi play, Odets himself and the Group Theatre have this to their credit—they have made an important breach in the Chinese Wall of Broadway, this wall of empty or psychologising, tickling star plays.

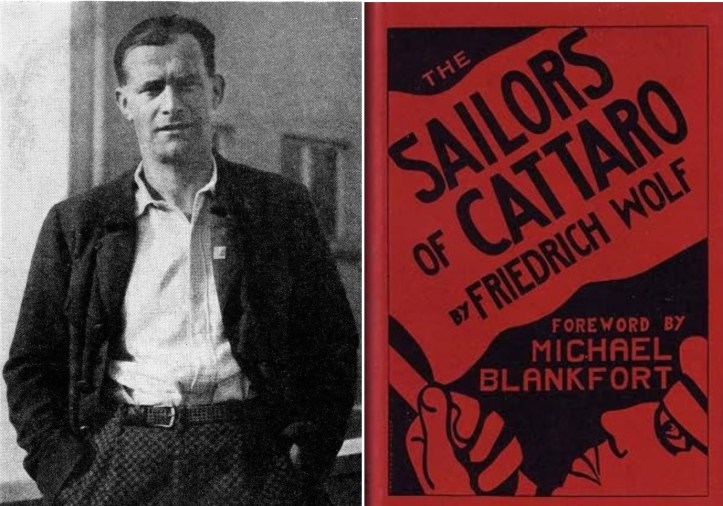

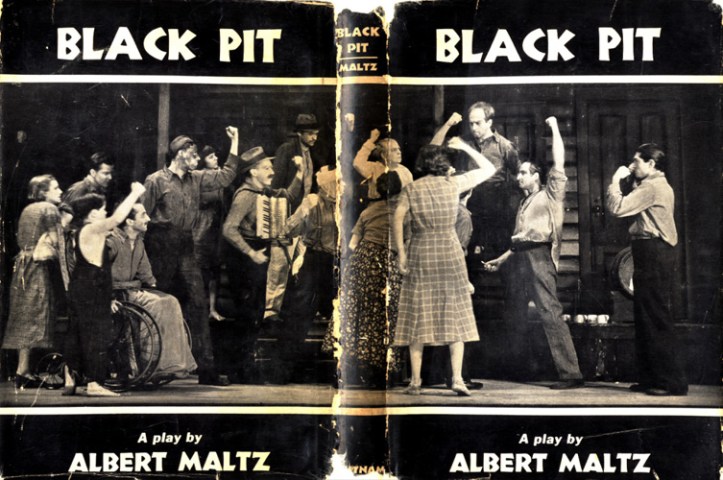

Black Pit…The Miner’s Play…The Theatre Union…The First Workers’ Theatre

The play and the executive board of the theatre are identical in The Theatre Union even more than in the “Group.” Except for my Sailors of Catarro all its other plays were written by the dramatist members of the theatre’s executive board…I refer to the plays of Sklar, Maltz and Peters. But the real basis of this workers’ theatre is the audience, the organized audience. It consists of workers, clerks, students and intellectuals. Some of the performances are bought out in advance by trade unions and organizations of the middle classes, office employees and professionals. The magnitude of this collective theatre-going depends of course on the quality and success of the play. The first play of the Theatre Union, Peace On Earth by Sklar and Maltz, ran for sixteen weeks, playing to 125,000 spectators; the second play Stevedore played twenty-three weeks to 200,000. This mass theatre-going by the workers in a professional theatre of New York is only possible with good organization of the audience and, above all, with unusually low prices. The cheapest seat in the Theatre Union costs thirty cents, that is cheaper than most seats in the big movies. The next best seats cost forty-five cents and the most expensive a dollar fifty. This is supplemented by a system of individual subscriptions for the dollar and the dollar fifty seats. Free tickets were issued to about 25,000 of the unemployed for every play.

It is obvious that this theatre, which is wholly supported by the toilers of New York, neither can nor will pay varying star salaries to its actors. The actors also work for collective salaries; no actor gets more than fifty dollars a week. And there are excellent actors such as Millicent Green, Martin Wolfson, Allen Baxter, in the ensemble, actors who played up to now in big, commercial theatres, and who left their highly paid jobs to put themselves at the disposal of this workers’ theatre. What is more, the ideology of the plays demands from each of these actors knowledge of the problems of the modern labor movement, participation in discussions, training courses and studio work. The ideological and artistic development of the acting company is a tremendous task, since a play based on the struggles of the present-day labor movement—a play portraying the complicated process of fascisation, the NRA mask, the Negro problem, the militarisation of the young in the conservation camps makes wholly new demands of the director, the actor and the scenic designer, demands hitherto unknown in America. It also makes demands: upon the spectator, who has been spoon-fed with the psychologising, dialogue plays of Broadway, or with the Greta Garbo magic and gangster films up to now.

In spite of all difficulties, the past four plays of the Theatre Union: Peace On Earth, Stevedore, Sailors of Cattaro and Black Pit were big hits. For the first time hundreds of thousands of workers were brought face to face with the problems of their own lives in a professional theatre. Problems of imperialist war, strikes, of race solidarity were shown on the stage in creative form. Discussion of these problems, of these plays, continued in public symposia of the spectators, and in the columns of the Left magazines such as New Masses and New Theatre. And here for the first time, the problem of workers’ and soldiers’ councils, unknown in America in practice, the problem of bourgeois and proletarian dictatorship, was for the first time the subject of lively discussion after the performance of Sailors of Cattaro, even by the middle class and white collar groups.

A pro and con symposium has also been held regarding Black Pit. Black Pit deals with the condition of the miners in West Virginia; it portrays the beginning of a strike. But the basic theme is the problem of the class consciousness of the workers. In Black Pit the central figure—the “hero”— is the worker, Joe Kovarski. He was sentenced to three years imprisonment for participation in a strike; he comes back to his young wife, to the family of his brother who is crippled in a mine accident. He looks for work in the mine again, but in vain—he’s blacklisted. He leaves his wife, looks for work in other states, but the blacklist follows him—he’s fired again everywhere. He has to return—extreme poverty at home where his young wife is expecting her first child…no bread, no doctor, no work. He can get work only as a spy, as a stool pigeon. After long and desperate struggle, he succumbs to the torture of poverty, of anxiety for his wife, and to the blandishments and threats of the “super,” the mine manager. The strike begins; the secret strike committee is arrested upon his information. But the crippled brother spots the traitor, the spy, in his own brother, his own family, to save which he committed treason, drives him forth. The strike begins none the less.

The play is well worked out dramatically; it is full of tension, with sharply outlined characters, colorful episodes. The scene in the boarding house in the Pennsylvania coal area, with its grim humor and its tragedy, is one of the best realistic scenes in recent drama. Another question for me, knowing the European miner as I do, was whether this figure of Joe—the stool pigeon—is a sufficiently typical figure to have been made the central figure of a workers’ play, a strike play. Can this Joe be raised to the level of a negative hero around whom all the spectator’s interest revolves? Is labor spying in the United States really so central a problem in strikes, whereas in Europe the problems in a strike are the betrayal of the reformist trade union leaders and the fighting united front of the working class. Moreover, can a proletarian of as good stuff as this Joe never redeem himself after betrayal committed in a moment of despair? Can’t he return to the class front, say by joining the picket line himself at the last moment?

Just after the premiere, and on many another evening later on, I talked with Albert Maltz on the importance of how the problem was put, precisely in his valuable play. He told me that for him the stool pigeon was only the dramatically clearest and most conspicuous representative of class treason, and by no means a central problem of strikes. He added however, that the figure of the hired stool pigeon played a tremendous role in strikes, both in point of numbers as well as in tactics. This was confirmed on April 24, in the big symposium on Black Pit and Muni’s Black Fury, by several miners from the Pennsylvania coal mines, among them one who had worked in the German coal area of the Ruhr. What is significant is how the serious and profound discussion initiated by this play continued for weeks in the press, in meetings and in private conversations. I was reminded of the best period of the Left and revolutionary German theatre: 1928-32, when a performance by the Piscator theatre, by the Young Actors’ Group or by the Troupe 1931 was the subject of conversation and discussion for months among the Left German theatre public. More important than anything else is that this lively discussion should not remain confined to the educational work of the Left New York theatre, but should succeed in establishing the practical basis for the united front of all toilers and anti-fascists even through ae theatre, so that the American workers may be spared an American Hitler.

It is also of the greatest importance that today the Theatre Union and the Group Theatre already form a strong basis for Left groups in the provinces, which have never seen a professional Left theatre up to now. Thus Peace on Earth and Sailors of Cattaro were played in the Contemporary Theatre of Los Angeles. Sailors of Cattaro will open the next season at the Cleveland Playhouse, one of the biggest theatres in the city, while Stevedore was played in Chicago. Waiting for Lefty was accepted and forbidden in Boston and Philadelphia, but then released for performance after a mass protest. It was put on and won the Yale University prize. A professional “Negro People’s Theatre” has now been formed in Harlem, its acting company including most of the original cast of–Green Pastures.

The Theatre of Action: Transition from the Amateur to the Professional…The Young Go First…A Play of the American Conservation amps

This agit-prop group, The Theatre of Action, has worked for five years under the leadership of its director, Alfred Saxe. The group of more than twenty trained actors showed us a cross-section of all their plays, of their five years of work. We saw various stages of development: from the old Left Prolet style through the biomechanics of Free Thaelmann and revue-like musical comedy scenes with master of ceremonies and group dancing, to two complete scenes of Molier’s l’Avare.

The group possesses quite a number of performers who can match the actors of the professional stage in quality and technique. His includes several excellently suited for songs and dance: together with the individual performance of Saxe in the role of the miser, the cabaret scenes were the group’s best achievement. What is lacking here again, is the repertory play, the play poetically created; up to now this group has been writing its plays itself. These short scenes do not meet the requirements of our European agitprop troupes nor even the central line of development of this group itself, which is really much further advanced. The group is now working on a very important full-length play on the fascist effect on youth; the shipments of «American youth to labour service camps, the so-called Civilian Conservations Camps, entitled the Young Go First. The Theatre of Action made its debut with this play as the beginning of a professional theatre.

Summary and Forecast: The Left American Theatre—One of the Most Important Theatre Outposts in the Capitalist World

I had a talk with a well-known bourgeois theatre theoretician, who is also one of the major critics of a big bourgeois magazine. He interviewed me regarding the Soviet Theatre, while I interviewed him on the last ten years of the New York theatre. I asked him, “Do you think that the plays of these last two years, such as Recruits, Awake and Sing! Waiting for Lefty, Till the Day I Die, Peace on Earth, Stevedore, Sailors of Cattaro and Black Pit, are phenomena of mode or chance, a change in genre?”

“No,” he answered. “They were too heavy as plays for that; our initial resistance to them was too great, and their success despite our resistance was too great and enduring. That is no thing of fashion.”

“Do you think that there is something else behind these plays? Something that makes these plays and the work of the collective possible?”

“Yes. There’s something new behind it, of course, but you couldn’t have done that with your Communism alone!” he explained.

“Isn’t it significant that all the good dramatists, all the dramatists who are also artistically worth while are Left, to put it mildly?”

“Of course, because they have a fixed Weltanschauung, and because this Weltanschauung is new and young.

“Do you think that the next season will lead to a relapse?”

“I believe,” he concluded excitedly, “that next season will be even more Left, faut de mieux. This is actually expected of the few talented young dramatists. If they were to retract their steps or merely remain stationary, it would be interpreted as weakness and their work up ta now would be considered as sentimentality and phrases! There’s is no turning back in the near future.”

That is not an isolated case. I heard everyone say that if the Left theatre—such as Group Theatre, Theatre Union and Artef, has plays as good as, and even better than those they have had up to now, if these theatres keep on working consistently, they will attract the New York theatre public, starved during the past two years. Even more, they will be able to extend and deepen their influence.

The Left theatre in New York has a special function. In view of the intellectual emptiness of the daily press and of most of the magazines, and the: stupidity of the film, the theatre can become a rallying point in this city of 7,000,000, a real cultural centre of all those who labor: all the workers, intellectuals and middle classes. The Left Theatre has seized its first chance to surprise the slumbering old theatre public and to win a new audience. It must now maintain its gains, in the face of rising demands by its own mass audience, and the inevitable competition of the commercial theatre with quasi-Left plays. What is needed is the sharpest kind of self criticism, and alongside the new generation of actors, new directors who emancipate themselves from the naturalistic psychologizing method of painting details, and who try to realise what the realistic dramatists have just begun in America: the portrayal of “typical characters in typical conditions.” In the Group Theatre and The Theatre Union the professional theatre has already moved close to the line of fire of the central problems of our time. It is really of decisive importance that here, at the beginning of the dramatic process, at the very start, the problems are posed correctly, that the arrow hits the: bull’s eye exactly. Political training of the acting collective and the dramatists, comradely discussions of common theoretical and organisation problems, of theme and problem, have already taken place, with actors and dramatists taking part. They are to be held regularly next season. The Left theatre in New York has a very good start in the two years already behind it. The responsibility it bears is gigantic. The Left New York Theatre today is not only one of the foremost battle fronts of the toilers of New York and America—it is without exaggeration the strongest and most outstanding outpost of the Left theatre in all the capitalist countries of the world.

Translated from the German by Leonard F. Min

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1935-n08-IL.pdf