Eastman at his very best in the essay from the scene of the Colorado State Militia’s killing grounds around Trinidad during the 1913-1914 Mine War.

‘Class War in Colorado’ by Max Eastman from The Masses. Vol. 5 No. 9. June, 1914.

“FOR EIGHT DAYS it was a reign of terror. Armed miners swarmed into the city like soldiers of a revolution. They tramped the streets with rifles, and the red handkerchiefs around their necks, singing their war-songs. The Mayor and the sheriff fled, and we simply cowered in our houses waiting. No one was injured here–they policed the streets day and night. But destruction swept like a flame over the mines.” These are the words of a Catholic priest of Trinidad.

“But, father,” I said, “where is it all going to end?” He sat forward with a radiant smile. “War!” he answered. “Civil war between labor and capital!” His gesture was beatific.

“And the church–will the church do nothing to save us from this?”

“The church can do nothing–absolutely nothing!” “Yes, this is Colorado,” he said. “Colorado is ‘disgraced in the eyes of the nation’–but soon it will be the Nation!”

I have thought often of that opinion. And I have felt that soon it will, indeed, unless men of strength and understanding, seeing this fight is to be fought, determine it shall be fought by the principals with economic and political arms, and not by professional gunmen and detectives.

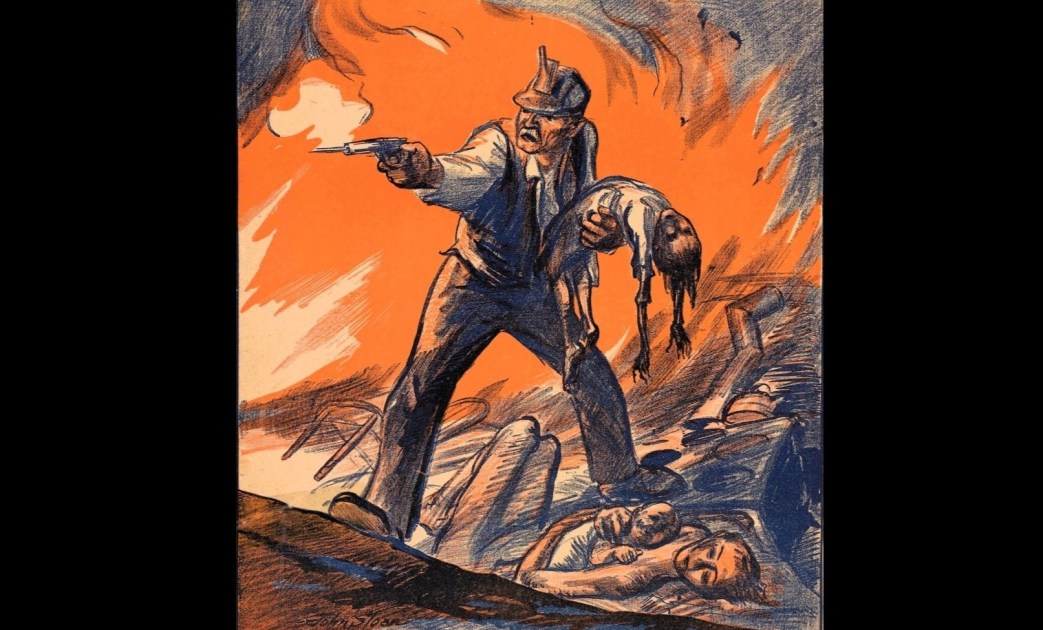

Many reproaches will fall on the heads of the Rockefeller interests for acts of tyranny, exploitation, and contempt of the labor laws of Colorado–acts which are only human at human’s worst. They have gone out to drive back their cattle with a lash. For them that is natural. But I think the cool collecting for this purpose of hundreds of degenerate adventurers in blood from all the slums and vice camps of the earth, arming them with high power rifles, explosive and soft-nosed bullets, and putting them beyond the law in uniforms of the national army, is not natural. It is not human. It is lower, because colder, than the blood-lust of the gunmen themselves.

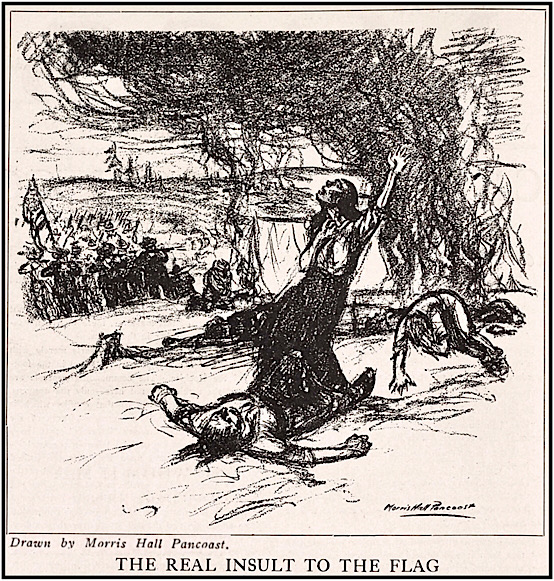

I put the ravages of that black orgy of April 20th, when a frail fluttering tent city in the meadow, the dwelling place of 120 women and 273 children, was riddled to shreds without a second’s warning, and then fired by coal-oil torches with the bullets still raining and the victims screaming in their shallow holes of refuge, or crawling away on their bellies through the fields–I put that crime, not upon its perpetrators, who are savage, but upon the gentlemen of noble leisure who hired them to this service. Flags of truce were shot out of hands; women running in the sunlight to rescue their children were whipped back with the hail of a machine gun; little girls who plunged into a shed for shelter were followed there with forty-eight calibre bullets; a gentle Greek, never armed, was captured running to the rescue of those women and children dying in a hole, was captured without resistance, and after five minutes lay dead under a broken rifle, his skull crushed and three bullet holes in his back, and the women and children still dying in the hole.

It is no pleasure to tell–but if the public does not learn the lesson of this massacre, there will be massacres of bloodier number in the towns.

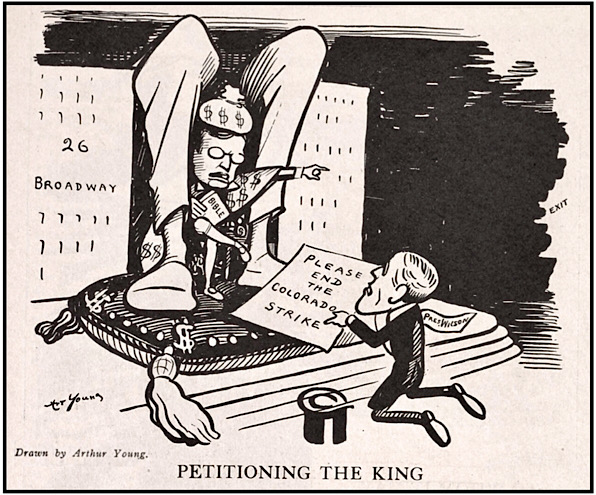

For you need not deceive your hearts merely with the distance of it. This is no local brawl in the foothills of the Rockies. The commanding generals are not here, the armies are not here–only the outposts. A temporary skirmish here of that conflict which is drawing up on two sides the greatest forces of the republic–those same “money “money interests” that have crushed and abolished organized labor in the steel industry on one side, and upon the other the United Mine Workers of America, the men who stand at the source of power. This strike in Colorado does not pay–in Colorado. It is a deliberately extravagant campaign to kill down the Mine Workers’ Union, kill it here and drain and damage it all over the country. And you will neither know nor imagine what happened at Trinidad, until you can see hanging above it the shadows of these national powers contending.

It is not local, and moreover it is not “western.” You can not dismiss the bleeding here with that old bogus about the wild and woolly west. Fifty-seven languages and dialects are spoken in these two mining counties. The typical wage-laborers of America–most of them brought here as strike-breakers themselves ten years ago–are the body of the strike. Trinidad with its fifteen thousand has more of the modern shine, more ease and metropolitan sophistication than your eastern city of fifty thousand. It is just a little America. And what happened here is the most significant, as it is the most devastating human thing that has happened in America since Sherman marched to the sea.

Between one hundred and fifty and two hundred men, women, and children have been shot, burned, or clubbed to death in these two counties in six months. Over three hundred thousand dollars’ worth of property has been destroyed. And the cause of this high record of devastation, in a strike so much smaller than many, appears bodily in the very first killing that occurred. On the 6th day of last August, Gerald Lippiat, a Union organizer, was shot dead on the main street of Trinidad by Belcher and Belk, two Baldwin-Feltz detectives, one of whom was at that time out on bail under a murder charge in his home state of West Virginia. That was three months before the strike, and for three months before that these two detectives and others had been in this district engaged in the business of spotting union members for discharge from the mines–a fact which illumines Rockefeller’s statement that only ten percent of his employees were union men.

“Just let them find out you were a union sympathizer,” I was told by a railroad man, “and that was enough to run you down the canyon with a gun in the middle of your back. It was an open shop for scabs–that’s the kind of an open shop it was.”

And this fact, verified on all sides, is not only sufficient ground for a strike, but it is ground for a criminal indictment under the laws of Colorado. So indeed are most of the complaints of the miners, for Colorado has a set of excellent mining laws stored away at the capitol. Five out of the seven demands of the strikers* were demands that their employers should obey the laws of the State–an incident which shows more plainly than usual what the State is in essence, an excellent instrument for those who have the economic power to use it.

I quote these formal demands in a footnote, but I think for human purposes the informal remarks of Mrs. Suttles, who tried to keep a clean boarding-house at the Strong mine, and “doesn’t care a damn if she never gets another job, so long as she can tell the truth and put her name to it,” are more valuable.

“What was the complaint? Well, it was everything. It was dirt, water, scrip, robbery. They kept everybody in debt all the time. Lupi was fired and compelled to pick up his own house and move it off the property, because he wouldn’t trade at the company store. Why, I says, if the Board o’ Health even, would come up here and take a look at the water out o’ this boardinghouse–show me any human being that’ll drink refuse from a coal mine! It was hay, alfalfa, manure–everything come right through the pipes fer the meri to drink and if that ain’t enough to make a camp strike, I’d like to know what ain’t! It was black an’ dirty an’ green an’ any color you want to call it–and when I’d enter a complaint they’d say, ‘Who’s kickin’?’ An’ I’d tell ’em the man’s name, an’ they’d say, ‘Give him his time! Let him get to hell out o’ here, if he don’t like it!’

“I give ’em a bit o’ their own medicine, too. They had a couple o’ these millionaire clerks down here from Denver oncet, an’ they didn’t have enough of the La Veta water brought down for their own table. I heard these fellers ask for a drink, an’ I took in a little of this warm stuff right out o’ the mine. Do you suppose they touched it? ‘What’s good enough for a miner,’ I says, ‘is good enough for you.’ I wanted to tell that before the Congress committee so bad I was just bustin’, an’ you can say it’s the truth from me, an’ I don’t care what happens to me so long as I’m tellin’ the truth.” She doesn’t care what happens to her, Mrs. Suttles doesn’t, but she cares what happens to other people, and I’m happy to be her mouthpiece.

You will know from her that there is nothing we are accustomed to call “revolutionary” in the local aspect of this strike. One sees here only an uprising of gentle and sweet-mannered people in favor of the laws they live under. In the mines they had learned to endure, and in the tents they surely did endure, smilingly as I have it from those who know, without impetuous retaliations, more hardship and continuous provocation than you could imagine of yourself–if indeed you can imagine yourself tenting four months in the winter snow for any cause. Patient and persistent and naturally genial–yet the militia, and the mine operators, and all the little priests of respectability of Trinidad are full of the tale of those “blood-thirsty foreigners,” “ignorant,” “lawless,” “unacquainted with the principles of American Liberty.”

As a pure matter of fact, so long as those foreigners remained “ignorant” and “lawless,” their employers were highly well pleased with them. But when they began to learn English, and acquire an interest in the laws, and also in the “principles of American liberty,” straightway they became a sore and a trouble to their employers–because their employers were daily violating these laws and these principles at the expense of their lives and their happiness, and they knew it. That was the trouble. And their employers, from Rockefeller down to the mine boss, are perfectly well aware of this, having brought them here in the first place for the express purpose of supplanting English-speaking Americans who knew their rights and had rebelled.

When you hear a man talking about “blood-thirsty foreigners,” you can be perfectly sure there is one thing in his heart he would like to do, and that is drink the blood of those foreigners–especially if he happens to be one of these hatchet-faced Yankees.

The strike was declared on September 23, and the companies, having imported guards for about two weeks before that, were ready for it. They were ready to evict the miners from their houses, dumping their families and furniture into the snow, and in many of the mines they did this. Those miners who owned the houses from which they were evicted, having paid for them although they were built upon the company’s land, must have received at this point a peculiarly fine taste of “American Liberty.” That is almost as fine as having a tax deducted from your wages, to pay for a public school privately owned and situated upon private property, or being compelled to pay fifty cents toward the salary of a Protestant town minister when you are a Roman Catholic. Miners in one case were not allowed to pass through the gate of the mining camp, in order to get their mail from a United States Post Office located within the gate called “Private Property”–another sweet taste of “American Liberty.” Was it such fortunes as this, I wonder, that led one of the strikers to run back among the blazing tents in order to rescue an American flag, “because he just couldn’t see that burn up”?

Early in October, say the strikers, an automobile containing Baldwin-Feltz gunmen stopped under the hills and fired into the Ludlow tent colony in the plain.

Early in October, says the superintendent of the Hastings mine, an automobile containing men coming to work in the mines, was fired on from the vicinity of the tent colony. The reader may solve this problem for himself. I can only picture the location of the mines and the colony, and let it stand that guerrilla warfare between the strikers and those men imported for their shooting ability, was frequent and was inevitable.

The mining camps are in little canyons, running up into a range of hills that extends due north and south, and the Ludlow tent colony was out on the wide plain to the east of these hills by the railroad track. It stood just north of the junction of the main line of the Colorado & Southern with branch lines running up to the mines. In short, it held the strategic point for warning strike-breakers on incoming trains. And to those who cannot believe the story of its destruction for the sheer wantonness of it, that little fact will be of interest. The tent colony at Holly Grove, West Virginia, shot up in the same wantonness by the same gunmen last year, was similarly situated. These tent colonies are white flags on the gatepost, flashing the signal “Quarantine” to the initiated, and it is very important for the unsanitary business within that they be removed.

So the gunmen would issue down the canyons, or shoot from the hills, and the strikers would sally out to each side of the colony, and shoot into the canyon or the hills. And this occurred often in the days of October, leading up to the pitched battle on the 28th, when the people in that vicinity seemed to be breathing bullets, and Governor Ammons ordered John Chase into the field with the militia.

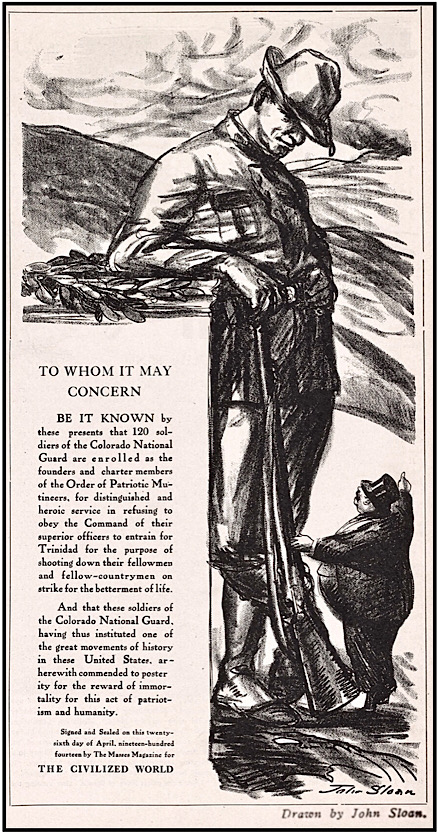

The militia came avowedly to disarm both sides, and prevent the illegal importation of strike-breakers, and they were received with cheers by the “lawless” strikers, who surrendered to them a great many if not all of their arms. For a week or two, in fact, the militia did impartially keep the peace. And the reason for this is that it had been asserted by the mine-owners, and believed by the Governor, that that famous “ten percent of union men” were forcibly detaining the rest of the strikers in the colonies, and that as soon as the ninety percent had the protection of the militia they would return to work.

In the course of the two weeks it became evident, however, that this happy thought was founded upon a wish, and that something else would have to be done to get the men back into the mines. Therefore the guns surrendered by the strikers were turned over to the new gunmen, and the protection of illegally imported strike-breakers began again. Began also the enrolling of Baldwin-Feltz gunmen in the Colorado militia; the secret meetings of a military court; the arresting and jailing by the hundred of “military prisoners”; the search and looting of tent colonies under color of military authority; and the forcible deportation of citizens. By such means and many others John Chase, riding about in the automobiles of the companies, made his alliance with invested capital perfectly clear to the most “ignorant” foreigner in the course of less than a month.

Thence forward we have to lay aside and forget the distinction between the private gunmen of the mine owners, and the state militia of Colorado–a fact which reveals more plainly than usual what the army is in essence, a splendid weapon for those who have the economic power to use it.

On November 25th, the strikers for the second time asked the operators to confer, and the operators refused.

On November 26th, Baldwin-Feltz Belcher was shot on the streets of Trinidad, not two blocks from where he had shot Lippiat in August. The militia cleared the streets, and indiscriminate arrests followed, strikers even being taken to jail, I am assured, in the automobiles of their employers. Habeas corpus proceedings were laughed at. Personal, liberty, the rights of a householder, of free speech, of assemblage, of trial by jury–all these old fashioned things dropped quietly out of sight, not only in the case of Mother Jones, which is notorious, but also in the case of the striking miners one and all. The State and organized capital were married together before the eyes of men so amiably and naturally that, except in the retrospect, one hardly was able to be surprised.

Sunday, April 19th, was Easter Sunday for the Greeks, and they celebrated that day in the happy and melodious manner of their country, dancing out of doors in the sunlight all morning with the songs of the larks. In the afternoon they played baseball in a meadow, two hundred yards from the tents, the women playing against the married men, and making them hustle, too. It was a gay day for the tent colony, because all the strikers loved the Greeks and were borne along by their happy spirits. Especially they loved Louis Tikas for his fineness and his gentle and strong way of commanding them. To all of them he seemed to give the courage that was necessary in order to celebrate a holiday with merriment under the pointed shadows of two machine guns.

But in the very midst of that celebration eight armed soldiers came down from these shadows into the field. Standing about, they managed to place themselves exactly on the line between the home-plate and first base, and during a remonstrance from the players, one of them said to another, “It wouldn’t take me and four men to wipe that bunch off the earth.” After some discussion among themselves, the players finally altered the position of their bases, and the soldiers decided not to interfere again. One of them said, “All right, Girlie, you have your big time today, and we’ll have ours tomorrow!”

On Monday morning, at about 8:30, Major Hamrock called the tent colony on the telephone, and asked Louis Tikas to surrender a mine-worker who, he asserted, was being held in the colony against his will. The person, in question was not in the colony, and Tikas said so. But the major insisted, so Tikas arranged to meet him on the railroad track, half way between the two encampments, and discuss their disagreement. Tikas went to the meeting place, and the major was not there. He returned, called him on the telephone, and again agreed to meet him alone at the railroad station.

They met and continued their discussion, but while they were talking a troop of reinforcements appeared over the hill at one of the military camps. The machine-gun at the other camp was already trained upon the colony, and a train-man tells me that at that time he saw militia-men running down the track, ready to shoot.

“My God, Major, what does this mean?” said Tikas. “You stop your men, and I’ll stop mine,” is the major’s answer as reported. But before Tikas got back to the colony, the strikers had left in a body, armed. Three bombs were fired off in the major’s camp–a prearranged signal to the mines to send down all the guards, officers, and strike-breakers they were able to arm. And immediately after the sounding of this signal, at the order of Lieutenant Linderfelt, the first shot was fired by the militia.

It is incredible, but it is true that they trained their machine guns, not on the miners who had left their families and made for a railroad cut to the southeast, but on their families in the tent colony itself. Women and children fled from the tents under fire, seeking shelter in a creek-bed, climbing down a well, racing across the plain to a ranch-house. “Mamma tried to protect us from the bullets with her apron,” said Anna Carich to me–a little girl of twelve years.

She herself plunged down the ladder-stair into the well–but no sooner arrived there than she had to go back and call her dog. “I says to him, ‘Come on, Princie. Come on in!’ but he was afraid or something, and when I stuck my head out, the bullets came as though you took a mule-whip and hit it on the floor. Papa pulled me back in, and Princie was killed. Maybe he wanted to go back after his puppy.” I guess that was it, for it was way off at the rear of the colony that I saw him lying in the grass.

There were women and children too that did not leave their homes in this volley, but simply lay flat or crawled into the earth-holes under the tents. And to these Tikas returned, and he spent the day there, caring for them, or cheering them, or lying flat with a telephone begging reinforcements for the little army of forty that was trying to fight back two or three hundred rifles against machine guns. But reinforcements came only to the militia, for they controlled the railroad, and in the evening, after a day’s shooting, they took courage under their uniforms, and crept into the tent-colony with cans of coal-oil, and set torches to the tents. I quote here the Verdict of the Coroner’s jury:

“We find that [here follow twelve names of women and children] came to their death by asphixiation, or fire, or both, caused by the burning of the tents of the Ludlow Tent Colony, and that the fire on the tents was started by militia-men, under Major Hamrock and Lieutenant Linderfelt, or mine guards, or both.”

When that blaze appeared, Louis Tikas, who had left the tent colony for a moment, started back to the rescue of those women and children who would be suffocated in the hole. He knew they were there. He was captured by the soldiers then. Is it likely he did not tell his captors where he was going and what for? The women and children were left dying, and Louis Tikas was taken to the track and murdered by K.E. Linderfelt or his subordinates.

Linderfelt is a man who had his taste of blood in the Philippines, in the Boer War, and with Madero in Mexico. He was second in command of this gang–a lieutenant. “Shoot every son-of-a-bitchin’ thing you see moving!” is what a train-inspector heard him shout at the station. And in that command from that man, brought here by the Rockefeller interests as an expert in human slaughter, you have the whole story of this carnage and its cause.

Is it a thing to regret or rejoice in that Civil War followed, that unions all over the state voted rifles and ammunition, that militia-men mutinied, that train-men refused to move reinforcements, that armed miners flocked into Trinidad, supplanted the government there, and with that town as a base, issued into the hills destroying? For once in this country, middle ground was abolished. Philanthropy burned up in rage. Charity could wipe up the blood. Mediation, Legislation, Social-Consciousness expired like memories of a foolish age. And once again, since the days in Paris of ’71, an army of the working class fought the military to a shivering standstill, and let them beg for truce. It would have been a sad world had that not happened. I think the palest lover of “peace,” after viewing the

flattened ruins of that little colony of homes, the open death-hole, the shattered bedsteads, the stoves, the household trinkets broken and black–and the larks still singing over them in the sun–the most bloodless would find joy in going up the valleys to feed his eyesight upon tangles of gigantic machinery and ashes that had been the operating capital of the mines. It is no retribution, it is no remedy, but it proves that the power and the courage of action is here.

* These are the formal demands of the miners: 1. Recognition of the union. 2. Ten per cent advance in wages on the tonnage rates and wage scale (in accordance with the Wyoming day wage scale). 3. Eight hour day for all classes of labor in and around the mines and coke-ovens. 4. Pay for all narrow work and dead work (including brushing, timbering, removing falls, handling impurities). 5. Check weighmen elected by miners without interference. 6. The right to trade in any store, and choose boarding-place and doctor. 7. Abolition of the guard system.

But let it be understood that the strike is not directed against any specific evil or evils, but against an entire system of peonage incredible to behold in this century–a system, against which unionism is absolutely the only defense. Recognition of the union or feudal serfdom in these mines–that is the issue.

The Masses was among the most important, and best, radical journals of 20th century America. It was started in 1911 as an illustrated socialist monthly by Dutch immigrant Piet Vlag, who shortly left the magazine. It was then edited by Max Eastman who wrote in his first editorial: “A Free Magazine — This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine; a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable; frank; arrogant; impertinent; searching for true causes; a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found; printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press; a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers — There is a field for this publication in America. Help us to find it.” The Masses successfully combined arts and politics and was the voice of urban, cosmopolitan, liberatory socialism. It became the leading anti-war voice in the run-up to World War One and helped to popularize industrial unions and support of workers strikes. It was sexually and culturally emancipatory, which placed it both politically and socially and odds the leadership of the Socialist Party, which also found support in its pages. The art, art criticism, and literature it featured was all imbued with its, increasing, radicalism. Floyd Dell was it literature editor and saw to the publication of important works and writers. Its radicalism and anti-war stance brought Federal charges against its editors for attempting to disrupt conscription during World War One which closed the paper in 1917. The editors returned in early 1918 with the adopted the name of William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, which continued the interest in culture and the arts as well as the aesthetic of The Masses/ Contributors to this essential publication of the US left included: Sherwood Anderson, Cornelia Barns, George Bellows, Louise Bryant, Arthur B. Davies, Dorothy Day, Floyd Dell, Max Eastman, Wanda Gag, Jack London, Amy Lowell, Mabel Dodge Luhan, Inez Milholland, Robert Minor, John Reed, Boardman Robinson, Carl Sandburg, John French Sloan, Upton Sinclair, Louis Untermeyer, Mary Heaton Vorse, and Art Young.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/masses/issues/tamiment/t39-v05n09-m37-jun-1914.pdf