Written in the immediate aftermath of Liebknecht’s murder, she even still holds out hope he is still alive, Esther Luria focus is not on his death, but on Liebknecht’s salutary life. Luria born in 1877 in Warsaw, to a Jewish family who fled to Switzerland for and education, becoming a Socialist and in 1903 receiving her doctorate in Humanities from the University of Bern. Luria returned to czarist-dominated Poland were she was active with the Bund during the Russian Revolution. After several arrests, including being held in the same prison as Rosa Luxemburg, Esther was exiled to a Siberian penal colony in 1906. A number of years later, she was able to escape and made her way to New York City in 1912. There she took up activity as an independent journalist for Yiddish-language Socialist and labor press and became widely known as a writer and lecturer, particularly on questions relating to Jewish, immigrant working class women of New York. After the reaction of the Red Scare set truly in, Luria drifted into poverty and obscurity in the city, with her exact death date being unknown, sometime in the 1920s.

‘Karl Liebknecht’ by Esther Luria from Justice (I.L.G.W.U.). Vol. 1 No. 2. January 25, 1919.

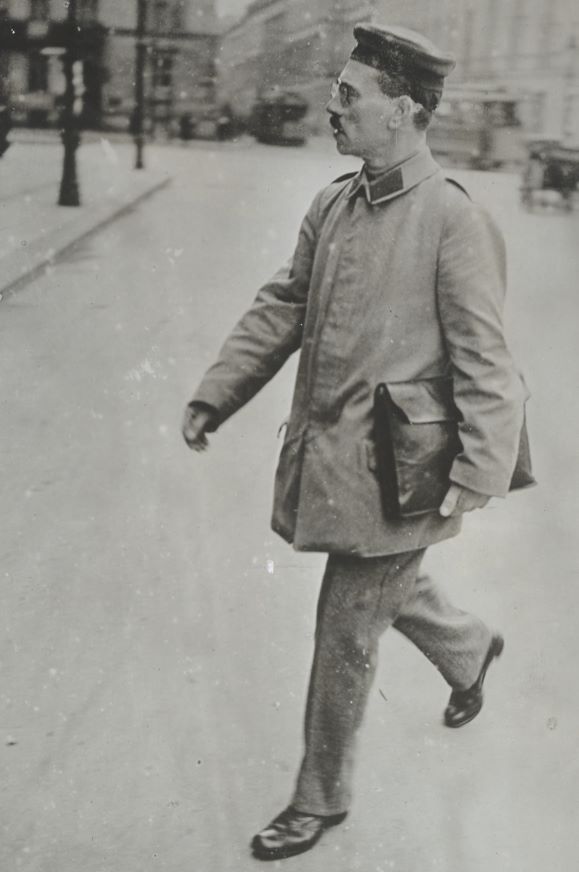

According to telegrams received from Berlin, Karl Liebknecht has fallen in his struggle with the Ebert government. But who knows? (Unfortunately the news of his death is too true. So is the death of the heroic Rosa Luxemburg. Both met their death at the hands of an infuriated mob. The Editor.) One cannot place much faith in reports which are received nowadays. More than one dead hero has been resurrected from the dead of late. We are, therefore, hopeful that Liebknecht is still alive and that he will continue his important work, his fight for a Socialist government in Germany. We shall, therefore, not write any epitaphs for him. But we shall rather review the activities and talk about the personality of the great German popular hero. Liebknecht is the real leader of the Spartacus group. Even the name of the party belongs to him. Because of the persecutions of his government, Liebknecht could not do his work openly. He was therefore compelled to adopt the old Russian methods of working in secret. And in his panphlets he would sign himself, “Spartacus.”

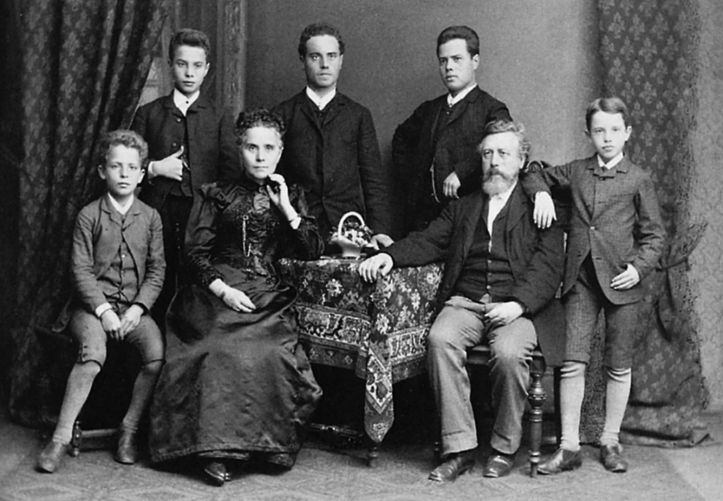

We are living in the twentieth century. For us, nothing supernatural exists. As we understand it, great people are endowed by nature, with extra ordinary gifts. But formerly this was different. Imagination would endow its heroes with supernatural forces. Heroes were not born like other children, neither would they grow up like other children. The hero of a Russian ballad is wrapped not in ordinary swaddling clothes but in iron armor. Had Liebknecht lived in those times, the legend would have put into his mouth the following words: “Mother, wrap me in conflict, do not feed me with milk but with the spirit of opposition.” And in the twentieth century we do not wish to say that Liebknecht sucked in the spirit of opposition, we may however say, that he was raised in this spirit.

Liebknecht was born 47 years ago. His father, the well-known founder of the social democratic party in Germany, was in prison at the time of the boy’s birth. He had been convicted for refusing to vote for the war budget. His mother used to say that she had passed on to her son the sufferings which she had had to endure, the courage and energy which she had had to display in those difficult times. She also instructed him to stand, like his father, for the people, and to fight for a brighter future. Liebknecht began to be interested in the life of the people while yet a student. At that time he organized literary clubs for the study of social problems. While a lawyer, Liebknecht had an office in Berlin with three partners, two of whom were his brothers. The office was always filled with various kinds of people. All wanted to see “Our Karl,” as he was called. An American Journalist, a personal friend of Liebknecht, described the office as follows: “Some wanted to get his advice in matters of law, others, German or foreign students, wanted to get his personal advice or material help. One sought employment, the other wanted to get some of Liebknecht’s articles for the press; one wanted to get some information from him, another wished to find out what was the entrance fee to the university. Still another wanted to know how to rid himself of the persecution of the police. And all received the needed advice from “Our Karl.” Liebknecht himself was one of those men whom one must love when one gets to know him. His home life was a very happy one. His second wife, the first one died, is a Russian woman. She is a graduate of the University of Heidelberg. She is an ardent social democrat, and supported Liebknecht in all his plans. In her, Liebknecht had a wife, a friend and a comrade. Personally there is very little that can be said against this lovable man. But the bourgeoise press does find things against him. Today one can read on the first pages of the American press, about Liebknecht’s great transgression because he sent his family to Switzerland, knowing that there I would be trouble in Berlin. A great crime, a father wishes to keep his children in safety during times of unrest at home.

Inventions, revolutions, new parties are not made in a single moment. They are created slowly, gradually. The same was also true of the work of Liebknecht. Not in a moment did he become the founder of a new party, not in a moment did he place himself in opposition to the official social democratic party in Germany, and not immediately did Wilhelm’s government see in him its most bitter enemy. Liebknecht began his fight about ten years before the beginning of the great war. Karl Marx and the old Liebknecht had foretold the evil outcome of militarism. These results were also seen clearly by the social-democratic party. But it took no definite step against this evil. Karl Liebknecht was the first one to take up this work. At the meetings of the social-democratic party, he brought in resolutions calling for systematic work among the soldiers against militarism. But Liebknecht’s resolutions were never adopted. He, however, did not lose courage, and himself took up the work. He lectured to the young men against militarism. He printed this lecture in book form. At first the government did not take notice of this book, but later it was confiscated and its author was indicted for treason. At his trial, Liebknecht uttered the following words: “The aim of my life is the overthrow of the monarchy. Like my father, who stood before a judge, just 35 years ago, and who was acquitted of the charge of treason, so I, too, hope that the time is not distant, when the principles which I stand for will be recognized as practical, just and honorable.” Liebknecht was sentenced to a year and a half in prison. While he was in prison, the workers nominated and elected him as member of the Landtag. On the day of the elections, tens of thousands of workers gathered about the building of the “Vorwaerts.” When the news of Liebknecht’s election was announced, there was a great demonstration of joy. One worker said to the other: “Only now will there be heard here true words of justice.” And these were prophetic words. Liebknecht fought whenever and wherever he had the opportunity. Not being able to fight against militarism in his own party and in the press, he nevertheless, found a way. He disclosed a number of frauds in the army. If Wilhelm had a personal friend, a general who was about to become a secretary in the war department, Liebknecht would come along and discover that Wilhelm’s friend was an impostor, and the latter had to withdraw from public life. Liebknecht even clipped the wings of the great Krupp. He showed the real worth of the great “patriotism” of the big manufacturer. The latter kept many spies in many of the European countries and also in America. With the aid of bribed diplomats, he would try to incite one country against the others, in order to call forth wars and get large orders. This German “patriot” would sell munitions in France at a lower price than in Germany.

In his activities against militarism, Liebknecht stood alone, both in his party and also in the legislative bodies. Liebknecht also fought against the monarchy whenever he had the chance to do so. Once the Landtag decided to set aside a certain sum of money for an opera house. Liebknecht said: “The opera house, for which we are to set aside the necessary outlay will outlive several generations. I hope that the time will come, when the institution will cease to bear the name, “The Imperial Opera House.”

Of course, it is self-understood, that when the war broke out, Liebknecht was not one of those who suddenly became “patriotic.” From the very start, he was opposed to the war. The first time he voted for the war budget in the Reichstag because the party had not yet come to any agreement, and he did not wish to be an exception, a thing which would have been against the party discipline. But shortly after that he did vote against the army budget. There was a time when he was the only one in the party to do this. Then the number of war opponents increased. This increase was a slow one during the first years of the war.

Liebknecht came out openly with his convictions. If they tried to throttle him in the legal press, he would make his utterances illegally. Liebknecht could not be silenced. He found a new way of attacking the government, a method which had been adopted in England but which did not exist In Germany. He would put various questions to the government and thus force it to speak out. The social-democratic delegates were not pleased with his conduct In the Reichstag. But they could do nothing against Liebknecht. He was finally expelled from the party. This could not be done officially because for this It was necessary to have a party meeting, and this could not be called. Liebknecht would oppose all evils of the government, the iron discipline in the camps and in the trenches, the atrocities in Belgium and in Poland.

Two years ago, in May, Liebknecht called out a demonstration. He held a speech before a large gathering that listened to him as if spellbound. In this speech he said: “We have three privileges; we may be soldiers, we may pay taxes, and we may keep our tongues between our teeth. Through a lie the German workers were forced to take part in the war, through a lie, they are being forced to continue the war. We do not want any more war, we want peace.”

The German revolution freed Liebknecht from prison. The number of his followers is ever on the increase. In vain does the press rejoice that with the death of Liebknecht, the Spartacus party will cease to exist. It will cease to exist just as Bolshevism ceases to exist in Russia.

It seems incredible that Liebknecht is already fifty years old. His courage, his energy, and his fearlessness are those of a much younger man. It seems that there are men who never grow old.

The weekly newspaper of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, Justice began in 1909 would sometimes be published in Yiddish, Spanish, Italian, and English, ran until 1995. As one of the most important unions in U.S. labor history, the paper is important. But as the I.L.G.W.U. also had a large left wing membership, and sometimes leadership, with nearly all the Socialist and Communist formations represented, the newspaper, especially in its earlier years, is also an important left paper with editors often coming straight from the ranks radical organizations. Given that the union had a large female membership, and was multi-lingual and multi-racial, the paper also addressed concerns not often raised in other parts of the labor movement, particularly in the American Federation of Labor.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/justice/1919/v01n02-jan-25-1919-justice.pdf