Another hard-fought battle in the small city of Paterson, New Jersey–site of an untold number of strikes, large and small. By the late 1920s much of the city’s textile industry was organized by the Associated Silk Workers, for which Harold Brown was publicity director.

‘Paterson Workers Rely on Mass Picketing’ by Harold Z. Brown from Labor Age. Vol. 17 No. 12. December, 1928.

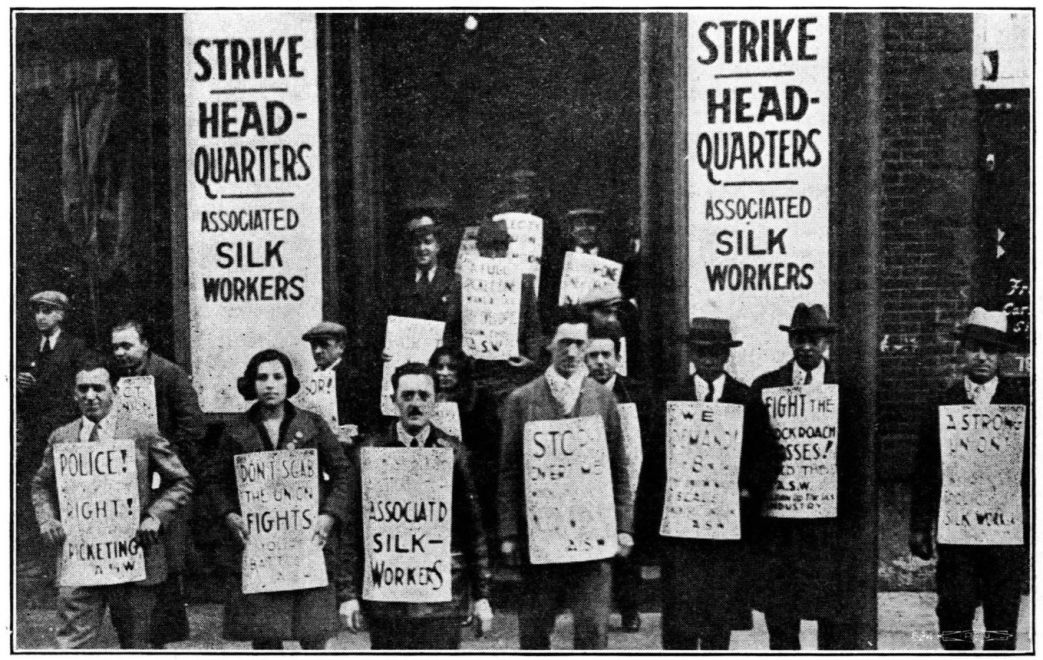

Silk Strikers Fight Small Bosses

PATERSON, city of silk–and labor struggles—is again on strike. For six weeks looms have been idle inside her broadsilk shops, while picket lines of weavers, warpers, twisters, and a half-dozen auxiliary crafts, organized in the Associated Silk Workers, tramp the pavements outside in search of that unique American prosperity which Mr. Hoover has just been elected to protect.

For a long time now Paterson Silk workers have been hunting that prosperity. They report that although the golden bird appears to fall an easy and impartial victim to the long-range artillery of Harry F. Sinclair or the General Motors Company, it has not for many, many moons come within shotgun distance of the Paterson proletariat. As far as the silk workers are concerned there has been a closed season on prosperity since 1924.

In that year they lost a strike against the multiple-loom system, which forced each weaver to run four looms instead of the two that he had run up to that time. Ever since then the history of the silk industry in Paterson has been one of gradual encroachments by bosses upon wages, hours, and working conditions.

When the strike was called October 10, 1928, piecework rates had been pared until weavers often got less pay for running four looms than they formerly received for turning out half as much product on two looms. Hours had crept up from eight daily to 9, 10, 11, 12—in some instances as far as 16. Union influence and power had slumped. The strikers walked out, making three demands: the 44-hour week, a uniform piece-work and time-work wage scale, and recognition of the union.

After six weeks of struggle three features of the strike landscape stand out prominently.

First, an impressive list of battles with bosses have been won. Of about 250 silk shops struck, about 175 have settled with the union. Of about 3,500 silk workers who walked out in response to the strike call, more than 2,500 are back at work under agreements that grant the union’s demands. Second, there is pressing need-of immediate relief for the remaining strikers if everything gained is not to be lost. Paterson, once renowned for her big silk mills, is today a city of “cockroach” silk shops—small, irresponsible, one-man businesses—employing on an average only 12 workers to a shop. The bosses who were in a hurry to settle have settled. Those remaining will be hard nuts to crack. Unless they are conquered before the strikers go back to work every settlement already made will be repudiated and conditions will drop back to pre-strike levels.

Police Repression Checked

Third, at least a temporary victory has been gained over police repression, long a deciding factor in breaking Paterson strikes. Police who started arresting mass picket lines during the second week of the strike found that the strikers could neither be provoked into law-breaking or bullied into abandoning picketing. They also found that the union was prepared to put up an aggressive legal and publicity battle, while the local magistrate seemed abnormally unwilling to convict orderly pickets on trumped-up charges of “disorderly conduct.”

So the guardians of public safety apparently decided to lay off silk strikers for the time being. From 50 odd arrests—nearly all for picketing—which occurred during the strike’s second week, the figure has slumped to a mere dozen for the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth weeks combined.

What the police will do in future no one call tell, for Paterson police in past strikes have been notoriously lawless in their attitude toward the civil rights of strikers. Many observers believe that the Baldwin assemblage case, growing out of a strike meeting held on the public square after the police had closed down the strikers’ hall during the 1924 strike, has made Paterson cops more cautious. It took three years to win this case, which was fought through to New Jersey’s highest court by the American Civil Liberties Union. But the final decision, handed down last May, was a stinging rebuke to the police, and completely vindicated Roger N. Baldwin and the nine silk strikers convicted with him of the high crime of “unlawful assemblage.”

Mass picketing has been the Associated’s trump card throughout the strike. At the beginning long lines brought out the sluggard shops which were slow in joining the walkout. During the early weeks long lines stood up against the police racket. Since then long lines, singing “Solidarity Forever,” shouting the union yell, carrying placards dramatizing the strike issues, have carried on the work. They not only cover the struck mills, but march through the town two or three times daily on their way from strike headquarters to the mills and back again.

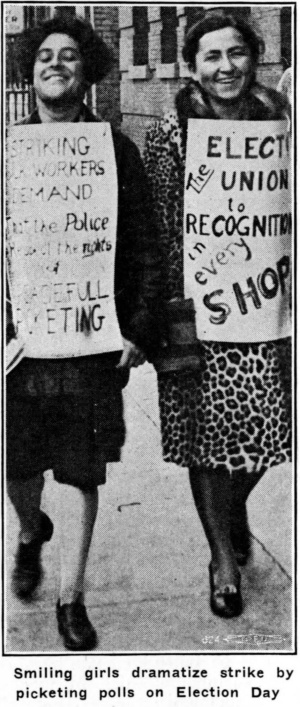

Resourcefulness in dramatizing the strike, not only to the public but to themselves, has been responsible as much as the strikers’ grit itself for the success achieved. On election day strikers picketed 18 polling places throughout Paterson, seizing the occasion to put Over a unique labor demonstration. Three silent pickets patrolled each of the polling places, wearing large placards with slogans presenting the strike issues in mock-political terms.

“Labor Without Representation is Tyranny Too,” said one. This was followed by “Elect Your Union to Representation in Every Silk Shop—Do it with Strike Ballots,” and “Every Picket is a Ballot for the 8-hour Day.” Others presented the strike demands as “our platform,” or urged working-class voters to organize for industrial action. Most prominent of all was the slogan the strikers have made their own: “Police Must Respect the Right of Peaceful Picketing.”

No arrests were made on this occasion because the demonstration had been so carefully organized as to give the police no excuse for interference, and because the police knew that arrests on election day would make the affair “big news” and spread the story all over the country.

The Associated Silk Workers is an independent industrial union, formed nine years ago. With about 6,000 members it stands out as the most powerful organized unit in the American silk industry. So far it has chosen to stand alone, in spite of pressing overtures both from the United Textile Workers and the left-wing National Textile Workers’ Union.

Membership Grows

To the Associated the strike has brought not only increased membership, but quickened activity and life. How Paterson silk workers are responding to its leadership is shown by the 3,600 members added to its rolls since the strike. Twisters and warpers, highly skilled auxiliary crafts, have recently formed branches within the Associated and are pushing vigorous membership campaigns.

An active Youth Section, formed since the strike from silk workers under 25 years of age, has a program of its own work within the organization. Just at present it is concentrating on a campaign to raise the morale of picket lines. The Youth slogan is “Young Silk Workers Fight Side by Side with Adult Silk Workers,” and they make no secret of it. “Youth pickets” are familiar sights on the lines, and adult picket captains say that wherever they appear efficiency jumps up 50 per cent. They are readily identified by their “uniform,” a broad white silk ribbon, worn diagonally across the breast, and bearing the words: “Don’t Scab. Join the Youth Section of the Associated Silk Workers.”

The Youth Section also promotes social and recreational activities in the union, and handles distribution of the Silk Striker, the official weekly of their union. A more extensive program awaits peace-time development after the strike is over.

Strikers’ women folk serve everywhere. Many think that the most important single contribution to the strike is their free-lunch stand at strike headquarters, where hot coffee and rolls are provided for early-rising strikers who report at 6:30 A.M. for the morning picket line. Certain it is that without these things the morning line would lose standing as a mass-movement.

Even the children take part in the strike through the Strikers’ Children’s Club, which formed itself some weeks ago when a group of strikers’ children got together in the union hall to practice labor songs. On Election Day some of the children insisted on helping to picket the polls. One little girl of 12 found herself the center of public attention, as, bearing a large placard inscribed “Silk Strikers Demand the Right of Peaceful Picketing,” she patrolled the sidewalk before a polling place, accompanied by another child and a woman picket captain.

“What’s that little girl doing here, anyway?” queried a well-dressed woman critically. “She’s not old enough to work.”

The child replied before the picket captain could explain. “I’m here for my father’s sake,” she said.

“He’s on strike.”

Appeal for Help

All these gains—hours, pay, union, members, morale—are well worth keeping, say Paterson silk workers. It is to keep them, not only for Paterson, but ultimately for all America, that the Associated Silk Workers is broadcasting to every wage earner, every labor organization, and every friend of organized labor an appeal for aid. Stressing the fact that unless picket lines and strike morale are kept intact right up to the last shop settlement, no part of the territory won can be held, the appeal says:

“Hundreds of strikers are already at the end of their resources. The Union is doing its best to meet the situation, but its war chest is not deep enough. Hundreds more will need assistance within a short time. Before the strike is over nearly a thousand families may have to be cared for by the union.

“Paterson, city of historic labor battles, is a strategic point not only in the textile industry, but in the whole American labor lineup. Our victory cannot fail to benefit all labor. If we should lose our defeat. would certainly harm all labor.

“We ask you to give now, and to give well. Give us both your moral and financial support. Help us feed our people so they can stay on the picket line. Make Paterson an 8-hour town.”

All relief funds should be sent to Fred Hoelscher, Treasurer, Associated Silk Workers Relief Fund, 201 Market Street, Paterson, N.J.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v17n05-may-1928-LA.pdf