The exiled Hungarian Communist and leading Comintern economist summarizes the background and enormous changes wrought by the First World War.

‘Economic Causes & Consequences of the World War’ by Eugen Varga from Communist International. Vol. 2 No. 5. August, 1924.

IN considering the world war, one often falls into the error of regarding it as an isolated and chance event, which might have been avoided by a better policy. The truth, however, is that war is inevitable under capitalism, and that a whole series of wars had preceded the world war. One can assert that during the whole of the half-century that preceded the world war, war was being waged on some part of the globe.

In their economic aspect these wars were mostly wars against unarmed peoples and served the object of bringing ever larger and larger parts of the world under the rule of the imperialist world powers. Thus, this long series of colonial wars served for the development of the imperialistic form of capitalism. The world war, in its economic aspect, was of an essentially different character. It was not concerned with the subjection of new territories to the imperialistic regime, but was a struggle among the imperialists themselves, for the re-division of the exploited colonies and semi-colonial territories. In order to understand this we will briefly sketch the structure of capitalism as it was before the world war.

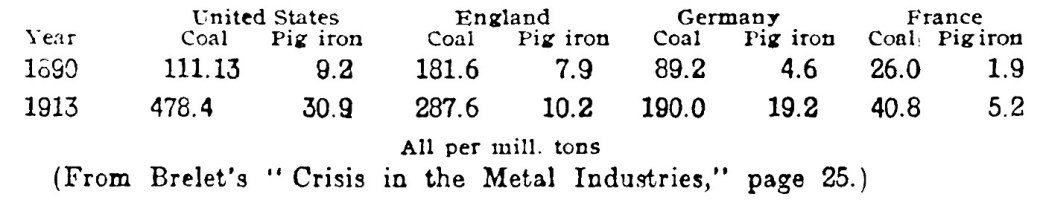

The economic features of capitalism in the quarter of a century which preceded the world war, was the enormous increase in production in capitalist countries. In illustration of this fact we will give only a few instances. The production of coal and iron, which is of especial importance for modern capitalists, developed in the following manner.

Even more strongly does the development of machinery show the rise of capitalism. The total horse power and machinery of the world has been estimated:

1896–66 million horse power

1911—200 million horse power

In a quarter of a century the machine power of the world was multiplied by three. It is estimated that of 200 million, 100 was used on the railways, 25 in water transport, and the remaining 75 million in industry.

The development of capitalism did not proceed at an equal rate throughout the world. Particular centres of capitalist development occurred. The main centre was in Western Europe, and was formed by Germany, France and England. Besides these, there were the other great capitalist powers of Austria-Hungary, Russia, and outside Europe, the United States of America and Japan.

The distinguishing feature of the Western European centre of capitalism was that, for the maintenance of its economy it imported large quantities of food and raw materials, and in order to pay for these, exported industrial commodities. These countries developed simultaneously, to a greater and greater degree, into exporters of capital. An ever-growing portion of accumulated capital was invested, not within these countries, but abroad in order to obtain the higher rates of profit from undeveloped countries, and thereby to counteract the tendency to falling rate of profit.1

At the same time production became highly concentrated and the means of production centralised. The control of industry of the imperialist countries, and thereby of the whole world passed into the hands of a continually diminishing number of great capitalists. The combination of capitalist undertakings into cartels, trusts and combines, made it possible for a quite small group of capitalist leaders in co-operation with the great banks to control the whole economic system of the country. Together with economic power they gained also political power, if not formally, certainly in fact. The great capitalists ruled the State, and guided its policy according to their own profit-making interests.

The expansion of capitalism, the exploitation of the colonies and semi-colonies, made it possible for the bourgeoisie of the imperialist countries to insure the workers of their countries rising standard of living. This fact made it possible for important sections of the working class in the imperialist countries to separate themselves from the general proletariat, and to become an aristocracy of labour. This provided the basis for revisionism, and obtained the endorsement of capitalist colonial policy by the Social-Democrats. It provided also the economic basis for social patriotism, and the co-operation of the industrial proletariat with their own bourgeois classes in the war.

The combination of the bourgeoisie into monopolistic organisations and their domination of the State machine, made it possible for them to monopolise the internal markets of each country. High tariffs shut out foreign competition and made it possible to throw the surplus of home production over the requirements of internal markets on to the world market, at much lower prices than home prices, and in many cases at below cost of production itself. The movement toward monopolistic control then passed to the outside territories and formed the basis of colonial policy. In particular, this took three separate but closely connected forms: (1) monopolistic exploitation of raw materials and national wealth of the colonies. It should be noted here, that in the rising period of capitalism, in the period of boom, there was an almost permanent shortage of the most important raw materials, and the bourgeoisie of each imperialist state had a keen interest in ensuring its own supplies of raw materials and controlling these by monopoly. (2) Monopolistically-controlled export markets for industrial products and (3) new monopolistic opportunities for investments of capital. With the development of capitalism, the latter became more and more important, and was closely related to the second point, since the new investment of capital abroad was naturally mainly carried out by the export of means of production to the less developed countries. This phase of highly developed capitalism, which is characterised by the pressure of the bourgeoisie to extend their monopolistically controlled markets by the addition of less developed territories, can be called imperialism.

The scramble of the bourgeoisie of the highly developed capitalist countries for the conquest of monopolistically controlled markets could not proceed without collisions, since most territories of the world were already appropriated. Hence a sharp conflict of interests between individual capitalist powers developed and this in connection with the interests of the armament industries, which exercised great political influence, led to severe conflicts between individual powers. We can distinguish the following concrete conflicts in interest.

The Anglo-German Conflict.

Of all the capitalist countries of Europe, Germany showed the greatest rise during this period. It conducted a keen competition with British industry in the world markets. At the same time, as the youngest of the capitalist countries, Germany, had been left almost without colonies. It got only the meagre leavings of Great Britain. Owing to this circumstance the German bourgeoisie felt itself at a very great disadvantage. It desired a “place in the sun,” that is, a share fitting its economic development, in the non-capitalist territories, for monopolistic exploitation. This pressure by the German bourgeoisie led to the most gigantic armaments on land, and above all on the sea. The latter was the main cause of England’s jealousy since hitherto it had alone ruled on the sea.

Because of England’s domination on the sea, Germany was forced to seek its spheres of influences more on Continental routes. Above all, it wished to subject Eastern Europe and Asia Minor to German capital. The building of the Bagdad railway, the construction of a direct connection between Berlin and Bagdad was the great conception of the German bourgeoisie. This necessarily, however, aroused the greatest disquiet in England, since the termination of the railway on the Persian Gulf threatened England’s rule in India. The economic cause which led to the blazing up of the world war, was thus the question whether Asia Minor should come under the influence of Germany or England. More generally, it was whether Germany should be recognised as an imperialist power equal with England on land and sea. The second main conflict of interests was between Germany and France, and this concerned the domination of Central Europe. The question had to be decided whether Germany, in the form of the United States of Central Europe, should be the ruling power in Europe, or whether this part should fall to France as it had been in the past, with the exception of the period from 1871 to 1914. This question is related with the problem of the Western European coal and iron mines.

A third conflict was the pressure of Russia towards an outlet into a sea of its own in the south, thus a pressure towards Constantinople and the India Ocean. The traditional struggle between England and Russia on this question was temporarily obscured by the attempt of Germany to reach the Indian Ocean by a railway line from West to East. The rivals, England and Russia, united in order to clear away the new rival for the moment more dangerous to England, Germany. Austria-Hungary, was completely materially and economically, absorbed into the German sphere of influence, while Japan and the United States appeared at the time to be standing outside these great conflicts of interest. These then, are the conflicts of interests which led to the greatest war in history.

Much has been written as to whether this war could have been avoided by a wiser policy. In general, a question of this sort is idle, and has only one meaning, that is, if one can draw lessons from it for the future. Before the war, there was a strong pacifist movement and popular economists, like Norman Angell, attempted to show beyond dispute, that war would be bad business for the bourgeoisie. This view in our opinion, has one mistake, namely, that it acts upon the assumption that the whole country including the bourgeoisie has one interest. As a matter of fact, the policy of the great capitalist countries was not decided by the people, and not even by the bourgeoisie, but by small groups of the higher bourgeoisie, the heavy industries, the great banks, the cartels, trusts, and combines. Even if the great middle strata in the various countries were economically ruined by the war, but special groups of leading capitalists were very greatly enriched by it.

That the bourgeoisie have not drawn pacifist lessons from the world war, is best proved by the fact that to-day, ten years after the world war, military armaments are increasing at a faster rate than before the war. In spite of the disarmament of Germany, arms are maintained, and the technique of slaughter is being perfected with the greatest zeal.

The question as to who was the aggressor in the world war seems just as idle. As a matter of fact, all the imperialist powers prepared beforehand for the world war, and the most decisive point in answering this question, seems to be the fact that all had prepared, therefore all can be said to be the aggressors.

II. The Economic Consequences of the World War.

The world war had severe consequences for the whole economic system of capitalism. It was the beginning of a period of crisis in capitalism, it shook the foundations of the whole capitalist system.

The world war itself was an enormous dissipation of wealth.

(a) About 20 million men in the prime of their capacity for productive work were drawn away from industry and occupied with slaughter.

(b) Many millions also were withdrawn from regular production, to work on the production of munitions of war.

(c) At the seats of war, means of production and other wealth were destroyed in enormous quantities.

(d) It is very difficult to state how far production was reduced by the consequent impoverishment and undernourishment of the peoples. In addition, the disabled are reckoned by the International Labour office at ten millions. With these bases we may reckon the fall in production caused by the war as follows:

1. The value of a years’ production of one man was on the average, 2,000 gold marks; 20 million participants in the war at 2,000 a year is exactly 40 millards a year, and in the four and a half years of the war, 170 milliards gold marks.

2. Ten millions in the munition industries also credited with 2,000 marks, represent in four and a half years, 85 milliard gold marks. At the same time decreased production shows itself in the under-nourishment of the people, | and in the reduction of the birth rate, which is only just beginning.

3. The direct damage caused by the war is difficult to estimate. For France alone it has been estimated at 26 milliard gold marks. In addition there are Belgium, East Prussia, Upper Italy, Serbia, Rumania and Russia; there are the sunken ships, totaling all together about 200 milliard gold marks. These three items together represent about 450 milliard gold marks.

4. The diminution of production by progressive impoverishment and its damage to working power cannot be estimated. On the other hand, production was increased by the fact that the whole reserve army of labour was employed ; women, children and the aged were employed in the process of production.

In his report to the Third Congress of the Comintern, Comrade Trotsky attempted to make a comparison of the wealth of the peoples before the war and their loss during the war. He produced the result that the national wealth of the warring powers before the war was 2,400 milliard gold marks, and that, during the war 1,200 milliard gold marks was annihilated. In addition the yearly decrease in production was 100 milliard gold marks, so that after the war, the national wealth of the warring powers was no more than 1,600 milliard gold marks.

This impoverishment in consequence of the war took its natural form. Building activity ceased completely, and has to a large degree not yet recommenced. Articles for daily use, such as furniture, clothes, etc., were not renewed; agriculture was carried on recklessly without care being taken to provide the necessary manure to replace the values taken out of the soil. Stocks of metals, textiles and food were used up. Foreign investments were used for the purchase of food, and of the most important raw materials, and were almost completely exhausted. Most of the belligerent countries who were able to do so, took up loans with neutrals, in order to anticipate and to use their future production.

Unequal Impoverishment in Different Countries.

The impoverishment varied in the different countries involved in the war; it is most intense in the Central European countries which were thrown back almost entirely upon their own internal production, and cut off from the world market by the blockade. In France and England, who had much capital invested abroad, and who received large loans from America, the impoverishment in the machinery of production and in other forms of wealth was less. America and the colonies on the other hand, were enriched as a result of war. The absence of European competition made a great industrial development in the overseas colonies possible, as the lack of shipping and the concentration of European industry upon munitions and other necessities of war prevented it from its ordinary production.

This increased industrial development in the colonial countries it has produced a permanent cause of crisis in West European capitalism, which can no longer support its own population at home by exporting manufactured goods. Hence, the strong support given by the capitalists to emigration schemes, and the marked revival of Malthusianism.

The Grouping of the Powers.

Of the seven great imperial Powers which began the war, three dropped out after the war:

Russia, owing to the revolution and the separation of its border States, which are destined by the imperialistic powers to form barriers against Bolshevism.

Germany, from whom all imperialistic potentiality and power were rent away (destruction of the fleet, disarming the army, military occupation, loss of Alsace-Lorraine, Holstein, Posen, Upper Silesia, and the subjection of the whole land to the economic control of the Entente by means of the Experts.) By these methods Germany has been transformed from an imperial power into a colony of the Entente, an object of imperialistic exploitation.

Austria-Hungary, was broken up into pieces with the result that the whole of Middle and Eastern Europe was Balkanised.

England and France have extended and completed their colonial possessions as a result of the war. England reigns from the Cape to Cairo, and from Cairo to India. The French colonies contain more than a hundred millions of inhabitants.

But the true victors in the war, nevertheless, are neither France nor England, but the United States. As a result of the war, the U.S.A. has changed from a debtor State to a creditor State. The Entente countries owe 10,200 milliards of dollars to America between them (of this Great Britain owes 4,100 and France 3,300). Before the war America’s external debt was far greater than the amount of capital it had invested abroad. To this must be added a large amount of American currency which is in circulation in the Central European countries, and in exchange for which the U.S.A. received real wealth in one form or another.

We have also omitted to mention the large loans given to private companies, and the credits allowed for goods. America’s position as the creditor of the Entente enables her to exercise strong political pressure upon the countries of Europe at every moment.

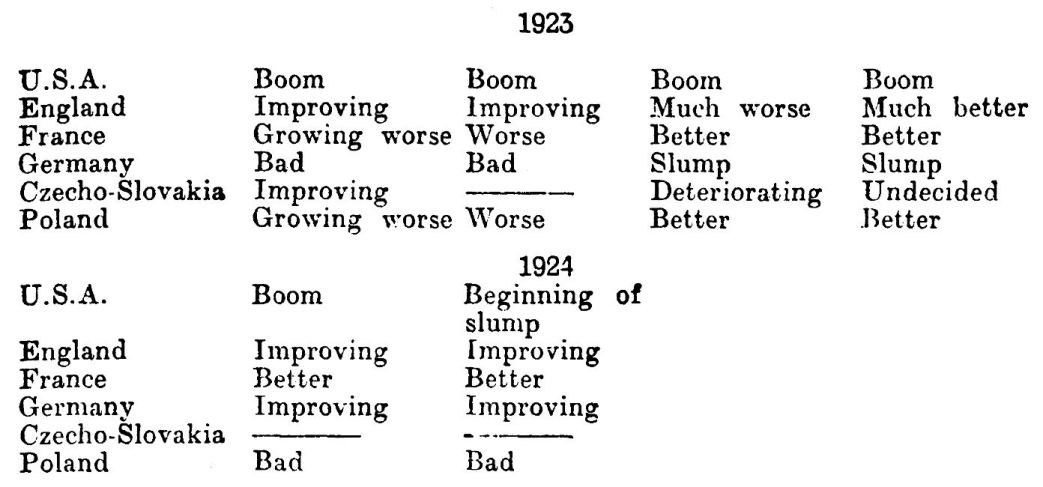

The result of the war has been to shift the balance of productive power to America. This is shown in the first place by the figures for the production of raw materials: America’s share in the world production of petroleum rose from 65.3 percent in 1913 to172.4 per cent: in 1923 her production of pig-iron rose from 39.7 per cent. to 61.6 per cent. and of steel from 40.1 per cent. to 61.6 per cent. of the world’s production. Production in most of her other industries is also on the increase. America’s automobiles constitute 90 per cent. of the world total. More than half the gold currency known to exist is to be found in the United States. In the last few years there has been a boom in the U.S.A., while all over Europe the slump remained. The boom of 1923 to April 1924 in America was practically limited to the U.S.A., and did not touch Europe at all.

The shifting of the balance of economic power to America is not only a result of the war, it only intensified a development which has already begun and which was due to the great natural resources of America (coal, petroleum, copper). While the production of coal in Europe is only possible at an ever-increasing cost, the cost of production in America is going down. Another source of wealth are the immense stretches of agricultural land which America has at its command (only 15 inhabitants to the square kilometre) and which are developed by all the most modern technical methods. For all these reasons Europe has been pushed back, both economically and politically, into a secondary role in comparison with the U.S.A.

Changes in Class Relations.

The impoverishment of the European countries is not universal, and does not extend to the classes of big capitalists or the owners of large estates; on the contrary these classes have seized even a larger proportion of the national income than they had before the war. Concentration and centralisation are continually proceeding. Since the war, the richer bourgeoisie has succeeded, mainly with the help of the depreciation in currency, in expropriating the middle classes. The whole cost of the war, in the form of war debts, currency inflation, and depreciation of currency has been ultimately thrown entirely on the broad masses of the people. The classes which were most heavily hit were small shareholders, people living on their savings, holders of life insurance policies, pensions, etc. Typical of this class was the formation at the last German elections of a party representing these disappointed small rentiers (the Party of the Destitute). The concealment of this impoverishment by loans and inflation which occasionally gave the appearance, for a time at least, of an increase in wealth, only hid their misery from the middle classes temporarily.

The liquidation of the war debts of the State and of private debts by inflation was so profitable for the bourgeoisie that the bourgeoisie of the victorious countries began openly to demand it. Inflation is infecting one by one the victorious States (with the exception of the U.S.A.) and the neutral countries.

The result of all this is a marked intensification of the class struggle. The small group of big capitalists is growing always more and more powerful at the expense of the impoverished middle classes. Trustification and the formation of cartels is increasing at the same time. Monopoly is used without limit for the exploitation of the consumer.

The Question of Reparations.

The development of this question is a complete reflection of the whole crisis of capitalism. The following periods may be distinguished:

1. Germany must pay the whole costs of the Allies. The result of this demand was the collapse of the currency, as in the final resort payments could only be made by an increased export of goods, or by gold. But the export of goods was restricted by all sorts of artificial barriers, while payments in gold, of which there was not a great reserve, could not be kept up. The sale of the paper mark in other countries and the handing over of securities, houses, land and other wealth to foreigners slightly prolonged the period during which Germany was able to pay something.

2. Germany can pay nothing more. Upon this followed the occupation of the Ruhr, which indicated the opening of the fight for the colonisation of Germany by English and French imperialism. France succeeded in conquering Germany, but had to give way to the economic superiority of England and America, and was, therefore, unable to carry out her scheme for smashing Germany completely to pieces.

3. Schemes of the Experts. These indicate the victory of England over the French attempt to smash up Germany. The Experts’ Report converts Germany, by means of strict and systematic control, into a colony of the Entente, all the most important branches of German production are registered and financially controlled. Permanent burdens are laid upon German industry by the new conditions demanded of it, and secured by guarantees. This same aim of control is the reason for burdening the German railways with yearly tax of nearly a milliard, and for introducing a cost of living index, so that in the extremely unlikely case that Germany’s economic condition should improve, this tax may be raised. The whole meaning of these plans is the permanent restraint of German industry, which has gained by inflation, and the restriction of its powers of competing with England and France.

The Crisis of Capitalism.

The years that have passed since the war have brought about a situation which may be called the war period of capitalism. Within this period booms and slumps succeed one another. But the whole system of capitalist society is involved in a permanent crisis, caused by the dynamical disturbances in the system of world capitalism. The most important signs of this period are:

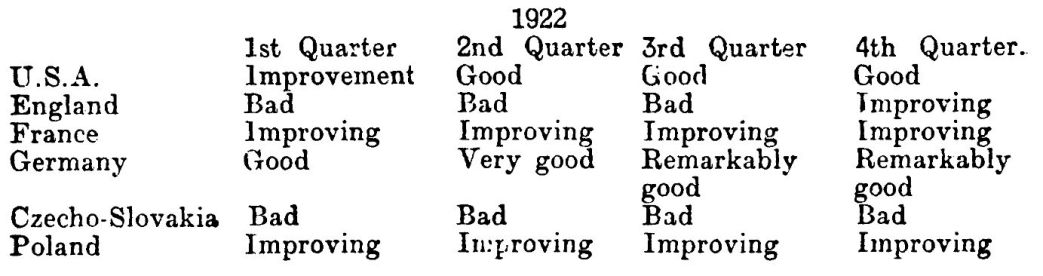

1. The irregular curve of the upward movement. Whereas formerly a homogeneous transition from boom to slump could be observed throughout the whole world, every separate country now has its own cycle of booms and slumps. In 1922-23, America had a boom, but Europe had none. The following table shows the irregular curve of these progressions:

2. The Special Crisis in the Industrial Countries of Western Europe.

This is the result of the industrial development in the colonial and semi-colonial countries, to which we have already briefly referred, and also of the beginning of a decline in productive work throughout the world. The industrial countries of Europe are not in a position to feed their population, as they did before the war, by the export of manufactured goods. The gigantic extent of unemployment in England and Germany is due in the first place to the decline in the export trade. Emigration is no way out of this difficult position, and especially since the U.S.A. are continually putting up fresh barriers against immigration. The European bourgeoisie cannot pay higher wages, and are, therefore, attempting to improve the economic state of the Entente countries at the expense of Germany; this attempt, however, cannot be called successful.

3. The Crisis in Agriculture. The cost of food does not keep pace with the cost of manufactured goods, which are kept artificially high by the monopoly of the trusts which rule the market (the scissors). The purchasing power of the people of Europe has been greatly reduced by the general economic crisis and by unemployment. A period of slump is beginning, although the agricultural production of the world has not increased at all. On the contrary, according to the figures given by a German bourgeois economist, Professor Sering, the acreage sown in 1923 was much less than before the war: 17 per cent. less wheat was sown, 8 per cent. less rye, 13 per cent. less oats, and 24 per cent. less barley.

The existence of the “scissors” led to a crisis in agriculture, and especially in those countries like the U.S.A. and Germany where the high prices formerly paid for agricultural produce had already established themselves in the form of ground rents.

All these conditions produce a general insecurity in economic relations, and this is intensified by the lack of a stable currency: speculation takes the place of production, crises due to inflation (resulting in a scarcity of goods) and stabilisation succeed one another. These economic conditions produce a permanent state of political insecurity ministerial crises, parliamentary crises and party crises, are the order of the day in nearly all the European countries.

The Burdens of the Proletariat.

At the moment, the proletariat is bearing the chief burdens of the war. The first revolutionary movement of 1918 impelled the bourgeoisie to make certain concessions (the eight-hour day, social improvements, rise in wages). When the instinctive revolutionary impulse of the working masses had begun to decline, the offensive of the capitalists of all countries against the advantages won by the proletariat since the war was opened. The first sign of it was the steady reduction in real wages to 50 per cent. or 80 per cent. of the pre-war standard. The wage reductions only took place amid great opposition. A decisive stage in the struggle was marked by the miners’ strike in the spring of 1921 in England, which ended with a complete defeat. In Germany the wages of the woodworkers had fallen by the autumn of 1923 to only twelve per cent. of their pre-war wage. Those of other classes varied between 15 and 45 per cent. of the prewar standard.

Side by side with these wage reductions goes the attempt of international capitalism to lengthen working hours—an attempt which has always met with considerable success.

The Social-Democrats and a certain number of bourgeois political economists, expect that the new method of dealing with the reparations question laid down in the Experts’ Report, will lead to a marked improvement in the economic situation of Europe. This is a mistaken idea, for the Experts’ Report really means the continuance of well-thought out and systematically executed plans for burdening the proletariat with the whole cost of the war, the middle classes having been already expropriated to a large extent and being also in no mood to submit to further exploitation. The success or failure of these plans depends upon the will to fight of the proletariat and on its capacity for fight. Economically the Experts’ Report marks a temporary relinquishment of reparation payments and the transformation of Germany into a colony of the Entente Powers in order, by artificial means to prevent German industry from developing far enough to injure the interests of French and English industry. The new scheme eases the crisis of capitalism in Germany, but will intensify its crisis in the industrial countries of Western Europe.

The period of crisis will last a long time unless a successful proletarian revolution makes an end of capitalism. The contradictions of capitalism are always being reproduced upon a more extended basis. The preparations for war against one another are being made at an increasingly rapid pace by the victorious powers. Despite the terrible results of the world war, the rich bourgeoisie is preparing for another war. In such circumstances, not bourgeois pacifism, but a proletarian revolution can hinder the outbreak of another war.

1. English capital invested abroad was estimated by Sartorius of Waltershausen, in 1914 at 32 milliard pound sterling; Paris estimates the profits in 1906-7 at 140 millions; foreign investments of France in 1900 was officially estimated at 30, and by Sartorius in 1906 at 40 milliard francs, by Arend in 1914, at 16 milliard francs, and the profits derived is estimated by Sartorius at 1.8 milliards annually. German capital invested abroad was estimated by Sartorius in 1916 at 26 milliard marks, and the profit at 1.24 milliards. If one adds the foreign investments of Holland, Belgium, Switzerland and other countries, a sum of 150-200 milliard gold marks is obtained.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/new_series/v02-n05-1924-new-series-CI-grn-riaz.pdf