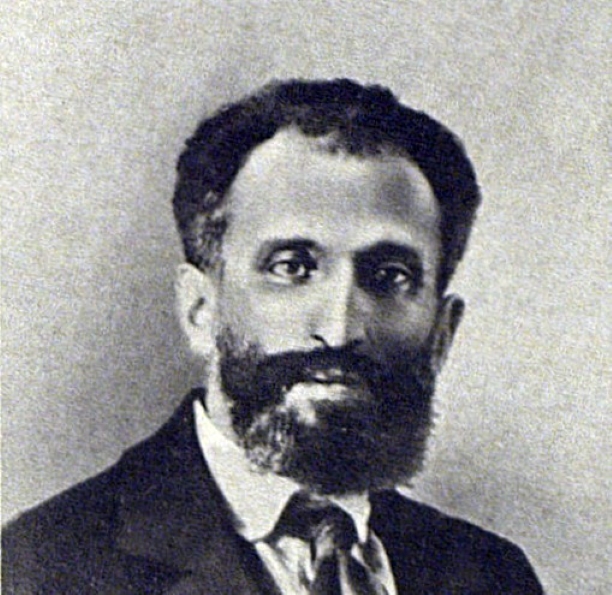

From the Lithuanian Jewish working class, with vast experience in the Russian and European labor and revolutionary movements since his teens, above and underground, as a mass and as a Party leader, Osip Piatnitsky was chosen to lead the organizational transformation of the Comintern and its parties as part of ‘Bolshevization’ in the mid-1920s. Moving from parties largely based on the geography of electoral campaigns inherited from Social Democracy (and, as in the case of the U.S., of different language groups) to nuclei based on workplace or political work centralized under district leaderships. While there is much to criticize in creating an internationally uniform apparatus based on the model of Czarist-era, underground Bolshevism, there was also much of value that was raised in the process. From factory newspapers to creating accountability, from women’s commissions to peasant fractions, the discussions touched on nearly every level of revolutionary organizing. Piatnitsky reports on the Comintern’s First Organizational Congress held in Moscow during March, 1925.

‘Conference of the Sections of the Comintern on Organisation’ by Osip Piatnitsky from Communist International. Vol. 2 No. 11. April, 1925.

INVITATIONS to this conference were sent to representatives of the Central Committee and the Berlin and Hamburg organisations of the Communist Party of Germany, to the Central Committee and the Paris and Northern district organisations of the Communist Party of France, the Central Committee and the Turin organisation of the Communist Party of Italy, the) Central Committee and the Prague organisations of the Communist Party of Czecho-Slovakia, and the Central Committees of the Communist Parties of Great Britain, Poland, Sweden and Norway. Actually representatives of all the Parties represented at the Enlarged Plenum took part in the conference. Furthermore, representatives of the largest local organisations in Germany and particularly of Czecho-Slovakia, took part which made it possible for the conference to become acquainted with the state of Party organisation, not only from the reports of the representatives of the various Central Committees, but also from the reports of local representatives.

Considerable interest was displayed in the conference by the delegates to the Plenum. Lively discussions took place on the reports. In this article, we will deal only with those questions dealt with, which in our opinion, present the greatest interest to the various sections of the Communist International.

Prominence was given to the question of organisation at the Fifth Congress of the Comintern. In the Organisation Commission of the Congress, the question was discussed as to whether it was possible to re-organise the Communist Parties outside of Russia on the factory nucleus basis. With the exception of a few towns in Germany and in France, and one town in Italy (Turin), nuclei had not yet been formed at that time, and the nuclei which existed in Germany and in Italy were not regular Party organisations with definite Party functions; they dragged out a miserable existence.

Quite a different situation existed at the time of the Organisation Conference. No one disputed the question as to whether the Communist Parties of the West should establish nuclei and whether the experience of Russia was applicable to the Western Parties. During the eight months that have transpired since the Fifth Congress, the Communist Parties and the Young Communist Leagues have achieved considerable success in organising factory nuclei. According to incomplete returns, in March, 22 Communist Parties had 8,822 factory nuclei and 18 Young Communist Leagues had 2,255 nuclei. The discussions that arose at the conference were over the questions as to how best organise these nuclei, how to attract the members of the nuclei to Party work and what place they should occupy in the Party organisation. As the debates at the conference centred mainly around these questions, we will deal with them here in detail.

Forms of Party Organisation Prior to the Fifth Congress. Passivity of Party Members.

In legal parties organised on a residential district basis, the members of the Party met together once a month and sometimes even once in three months at town meetings, and in large towns at district meetings, at which reports from the various Party organs were read and various Party questions discussed.

Connection between the Party committee and the members of the Party was maintained by these meetings and also by the Party dues collector, who visited the homes of the members and collected the Party dues.

In illegal and semi-legal Parties organised on a residential basis, the membership was divided into groups of ten, at the head of which was an elected or appointed captain (“functionary”). The various leading Party bodies were connected directly with the functionaries. The groups of ten organised on a residential basis carry out Party work only during campaigns, during elections, demonstrations, etc. In ordinary times, the functionary did the work, and even then, not in all cases. This form of organisation created a mass of passive members, for the work was done without them and it was no one’s business to draw them into the work. In the Berlin-Brandenburg district, where Party nuclei already exist, out of 20,000 members only from 10,000 to 12,000 members do any kind of Party work (official report of Organisation Bureau of Berlin-Brandenburg Committee), and in Czecho-Slovakia only 25 to 30 per cent. of the members are drawn into Party work.

The Party members belonging to a given group are usually employed in different factories. Consequently, the Communists working in the same factory, prior to the organisation of factory nuclei, did not know each other. Under the old system, the Party members worked among the non-Party workers in a given factory at their own risk, without any guidance, without system or plan. Cases have occurred whiten Communists unconsciously have acted against their fellow Party members owing to the fact that they did not know each other. Moreover, the district and town Party Committees did not know in what factories there were Communists, and in what numbers, because members were registered according to the place of residence. Since factory nuclei have been organised by both legal and illegal parties, Party work has revised—as was admitted by many of those present at the Conference, even by those who, at the Fifth Congress, were opposed to re-organisation on the factory nucleus basis. The members of the Party in the nuclei have been drawn into Party work, new members have been made from among workers at the bench, new readers have been obtained from among the factory workers for the Party press; the Communists are conducting work according to a definite plan drawn up by the nucleus. The recent large Labour demonstrations which took place in Paris, Berlin, Prague and Kladno have shown that through the nuclei the Communist Parties have established connection with the working men and women in the factories.

But the factory nuclei do not work well everywhere where they exist. From the reports of the representatives of the Central Committees and local organisations of various Parties, it is evident that the proportion of factory nuclei which work badly is very large. In the Communist Party of France, out of 2,500 nuclei, 1,000 worked indifferently, 750 worked badly, and 750 worked very well. In the Berlin-Brandenburg districts, out of 1,800 nuclei, 540 worked tolerably well, while the remaining 1,260 have not been drawn into the work (report by the Organising Bureau of the Berlin-Brandenburg Committee), in Chemnitz only 50 per cent of the existing nuclei are functioning. The situation is not better in Czecho-Slovakia. There, out of 942 factory nuclei, barely 45 to 50 per cent. are functioning. The same may be said with regard to the Young Communist League.

The large proportion of inactive and badly functioning nuclei creates a dangerous situation for the further development of these factory organisations. Furthermore, it will be very difficult to convince comrades who belong to inactive or badly functioning nuclei of the necessity for the further existence of these organisations.

What is the reason for the existence of so large a number of inactive nuclei?

In the first place, very frequently the competent leading Party bodies have failed to devote sufficient attention to the nuclei after they have been formed. No instructions were given them, the manner in which they worked was not investigated, Party questions were not brought up at the nuclei meetings for discussion and the Party slogans were not explained. In short, the nuclei were not imbued with political life.

Secondly, in certain countries where unemployment is very prevalent, and Communists are victimised by the employers, the Social-Democratic and trade union bureaucrats usually help the employers to discover the Communists in the factories, and secure their dismissal. For that reason, the Communists in the factories fear to develop their work.

Thirdly, in large towns, like Berlin, Paris, London, New York, etc., the workers live at a great distance from their places of employment. The arrival and departure of workmen’s trains are adapted to working time. When Communists stay to attend a meeting or to carry out some Party duty, they have to miss their train, which entails a long wait for the next train.

And fourthly, in Czecho-Slovakia and Germany the previous forms of organisation according to residence—the groups of ten—have been allowed to continue to exist side by side with the factory nuclei. Age-long Social-Democratic habits, victimisation by employers, inconvenient train services, the lack of vitality of the factory nuclei and the continued existence of the old residential district organisation at which the members continue to meet and discuss Party questions, all this prevents the development and the intensification of the activity of the factory nuclei which have been formed after so much effort. For these reasons, the Conference on Organisation in its resolution, which was endorsed by the Enlarged Plenum, calls upon the Communist Parties to devote serious attention to giving definite instructions to the already existing factory nuclei, to transfer the centre of Party work to these factory nuclei, and urged the necessity for establishing closer connection thar: exists at the present time between the factory nuclei and the respective Party bodies. The resolution urges that in those districts where the majority of the members are already organised in factory nuclei, the groups of ten and residential district organisations must be dissolved. Unless these latter are dissolved, it will be difficult to induce the members of the Party to attend the meetings of and work in the nuclei.1

Functionaries and “Responsible Persons” (Active Workers.)

The passivity of Party members to which reference has been made, gave rise to the institution of so-called functionaries and responsible persons, who, as a matter of fact, decided all political and Party questions in spite of the fact that they had no authority from the members of the Party to do so. This in its turn fostered the inactivity of the members of the Party, because as a consequence of this, they were not drawn into the discussion and decision of economic, political and Party questions. Meetings of functionaries and responsible persons began to take the place of district and town conferences, and cases have occurred when such meetings have passed resolutions directly contrary io the decisions of the corresponding Party Conference. The system of functionaries is widespread in those countries where strong, Social-Democratic organisations existed (Germany, Czecho-Slovakia, Austria, etc.), from which the Communist Parties inherited the system. Every year, the Party committees give to Party, trade union, co-operative society, etc., workers a mandate to take part in meetings of functionaries in the given district or town. The Competent Party committee convenes these meetings. During the course of this year, the functionary continues to regard himself as such and continues to attend the meeting of functionaries even if he has ceased to perform the work which gave him the right to attend these meetings. The minutes of the Organising Bureau of the Berlin-Brandenburg Committee show that of 48 functionary mandates examined, only one was owned by a comrade who was a member of a nucleus, of 50 functionary mandates in Berlin District No. 15, only two belonged to comrades working in nuclei. Consequently, the nucleus workers (secretaries and chairmen) of Berlin represent only an inconsiderable proportion at the meetings of Berlin functionaries and have little influence on its decisions. In his report on the Kladno (Czecho-Slovakia) Party organisation, Comrade Kreibich stated that the meeting of functionaries decide all important questions, while the Party Conferences, which are rarely convened, discuss only trifling matters.

At the conference and in the commission set up to examine the form of organisation of the leading Party bodies, consisting of representatives of the nine largest Parties and of the Young Communist International, the question of the system of the functionaries gave rise to a very heated discussion. With the exception of the representatives of the Communist Party of Germany who proposed that the meeting of functionaries be given the right to decide questions, everybody came to the conclusion that the existence of the system of functionaries in its present form was harmful.

In its resolution, which was endorsed by the Enlarged Plenum, the Conference on Organisation did not object, but even recommended to the local Party bodies to convene conferences of secretaries or of nucleus committees, of secretaries or fraction committees in mass labour and peasant organisations, or of comrades managing any particular branch of Party work, to discuss Party, trade union, cooperative, questions or campaigns; but it opposed the present system of functionaries and strongly objected to substituting district or town conferences by meetings of functionaries. The resolution recommends that periodical district or town Party conferences be called and that the agenda of such conferences be preliminary discussed in the nuclei, after which the latter are to elect delegates to the Party Conference.

Factory Nucleus Newspapers.

Factory nucleus newspapers rapidly became popular in Western Europe. In Germany more than 1,000 are published and in France, nearly 500. Such newspapers are also published in Czecho-Slovakia, Austria, England and in other countries. The factory newspapers in the West differ from the factory newspapers published in Russia, in that the latter are wall newspapers, while in the West, it is not possible to display these newspapers on the factory walls. Consequently, they are published illegally, in various ways (on mimeographs, typewriters and sometimes printed) in hundreds and sometimes in thousands of copies and distributed among the workers in the factory. In most cases these newspapers are got up exclusively by the efforts of the members of the nucleus. Some of the newspapers contain very interesting drawings and cartoons. The nucleus newspaper has become an inseparable part of nucleus work and it has become the principal medium through which the nucleus exercises its influence upon the workers in the factory in which the nucleus cannot act openly. In Italy, the Party Committees, instead of factory newspapers, publish small leaflets dealing with important questions which have considerable influence upon the workers. Many of the factory newspapers still suffer from numerous defeats. Some are devoted exclusively to politics and repeat what has been said already in the Party daily, while others are devoted exclusively to affairs connected with the factory, without linking them up with the slogans of the Party. The Conference on Organisation passed a resolution on factory nuclei newspapers recommending the Parties to continue publishing such newspapers and making it obligatory for the secretaries of district Party committees, or the agitation and propaganda departments of these committees, to devote serious attention to these newspapers and keep them well instructed. The resolution points out the good and bad sides of the newspapers already published.

The Weakness of Local Party Apparatus.

It was established at the Conference on Organisation that in a number of towns in Czecho-Slovakia, France and England, there is not even one Party worker engaged fulltime on Party work. The Party apparatus is concentrated principally in the provincial committees. In 39 districts in the Paris area, the district committees commence Party work after working hours, because even the secretary of the district committee is employed in some factory or office. In some towns in England, the town committees have no full time workers, and, of course, full time district workers is out of the question. In large towns in America, like Chicago and Boston, there are not even district committees, but only town committees.

It is quite impossible under such conditions to build up a strong, disciplined, centralised, flexible organisation.

How can a provincial committee or a town committee in a large town react quickly to events, intervene in labour conflicts, if the district committees have no permanently operating apparatus, and if there is not even a full time district secretary? How can the provincial or town committee quickly give instructions if there are no permanent organs in the districts to convey these instructions to the proper quarters? Such a state of affairs might have been tolerated under the former system of organisation when the members of the Party were convened once a month or once every three months, and when the functionaries and responsible members decide all the questions for the Party instead of the members deciding them. But this cannot be tolerated when the Party is re-organised on a factory nucleus basis, for we shall be able to establish ourselves firmly in the factories only when our nuclei will be active and intervene in all the conflicts between the workers and employers; when they will be able to direct the discontent of the workers along the correct lines of the class struggle; and this will be possible when the district or ward committee will be able to give proper and correct instructions to the nucleus and will be in a position to see that these instructions are carried out. For this it is necessary for at least one comrade, say the secretary, to be a full-time Party worker. The Conference on Organisation called the attention of the Communist Parties to the necessity for intensifying the work of the district and ward committees and to appoint a full time Party worker tor these committees.

The Weakness of the Communist Fractions in Non-Party Mass Worker and Peasant Organisations.

It became evident at the Conference that the Communist fractions, where they existed, work very badly, that their relations with the Party organisations are not regular and that the Party organisations have not devoted sufficient attention either to the organisation of Communist fractions or to their work.

The position with regard to parliamentary fractions is more or less satisfactory. These are under the constant control and guidance of the Central Committees of the Parties, but even in these, symptoms of social-democracy are to be observed in the tendency of the parliamentary fractions to strive to become completely independent of the Central Committee of the Party (Czecho-Slovakia).

1. The instruction on organising factory nuclei endorsed by the Fifth Congress, permits of the organisation of Party members not employed in factories, in street nuclei. Members of the Party who belong to factory nuclei, but who work at a great distance from their place of residence, must, in addition to their membership of a factory nucleus, register with the Party Committee in the district where they live. After working hours and on holidays, the Party member may be given definite duties by the residential district committee.

The position with regard to the relations between the Communist organisations and the Communist Party fractions in Landtags and similar bodies can be regarded as tolerable, although Communist fractions in bodies functioning in districts remote from the centre still work independently of the Party.

In the peasant parties in many countries (Rumania, Yugo-Slavia, France, Germany and America) no fractions have been formed and the Communists in these organisations are unorganised.

In many countries no fractions have been formed in sport organisations, and in those places where they have been formed, they work isolatedly, without guidance and without local or national organisation.

The situation with regard to fractions in the trade unions is no better.

Communists regard it beneath their dignity to join Christian, National Socialist, Liberal and other trade unions, in spite of the fact that in Germany and Czecho-Slovakia, these organisations still have a considerable working class membership. When trade unions affiliated to the Profintern were formed in France, Czecho-Slovakia and in Germany, the Communists left the Amsterdam trade unions and transferred to the red trade unions. Consequently, the Amsterdam unions were relieved of the Communists and their work and in the red trade unions, the Communists who principally lead these unions, consider it superfluous to form fractions to work under the guidance of the Party organisations. As a result of all this, a tendency is observed as in Czecho-Slovakia, for example, for the Communists in the trade unions affiliated to the Profintern to strive to throw off the influence of the Party organisation and to act independently.

In France and Czecho-Slovakia, the Communist Parties, through their members belonging to the trade unions affiliated to the Profintern, were able to establish connection with the factories. But the fact that no Party nuclei had been formed, prevented the members of the revolutionary trade unions from conducting systematic work (in France) and led to the Communist members of the revolutionary trade unions putting up candidates for the factory committees and other bodies without coming to an understanding with the Party organisations concerning these candidatures (Czecho-Slovakia).

The Social-Democratic Parties in Germany, Austria and Czecho-Slovakia have no factory nuclei, but they are 30 closely connected with the Amsterdam trade unions that, through them, they are able to exert their influence upon the workers in the factories.

The Communist Parties should do the same thing through the medium of the Communist members of the trade unions; they should exert their influence through the fractions. But these fractions must work under the guidance and control of the Party organisations.

In spite of the fact that our Party in England has considerable influence in the Minority Movement, it has not consolidated this influence organisationally, and has not formed strong fractions.

In Germany many of our Party members remained in the Amsterdam trade unions and many who left are returning to them. In many places Communists are elected to the provincial management committees of the unions and in some places even have a majority; but right up to this day, neither in town, provincial, area or national bodies have fractions been formed. The work of the fractions in Germany is not conducted systematically, and the amount of attention which their importance deserves is not paid to them.

The Conference on Organisation devoted considerable attention to the work of the fractions and drew up a list of instructions making it obligatory upon all the sections to take up this work in the most energetic fashion and to form fractions in all the non-Party mass organisations.

Organisational Forms in the Workers’ Party of America.

It will not be superfluous to say a few words concerning the Workers’ Party of America, for it reveals the chaos in Party construction that exists in certain sections of the Communist International.

The members of the Workers’ Party of America are organised not in factory nuclei, but according to nationality. The Lithuanians, Letts, Finns, Swedes, Yugo-Slavians, etc., are organised in separate organisations, each having its own national and local apparatus. Of such organisations there are seventeen. All of these together form the Workers’ Party. These separate national organisations collect the dues from their members, have their own daily and weekly newspapers, their own printing presses, their own clubs and halls.

Actually the national centre—the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party, and the town and State committees of the Party are dependent upon the will of these seventeen separate organisations. If the latter desire to carry out the decisions of the Central Committee they do so; if not, then they are not carried out.

These seventeen separate organisations send their representatives to town and State conferences in proportion to: their membership. These conferences elect town and State committees respectively. The State conference elects delegates to the national conference.

The State committees and the Central Committee only appear to bear the character of Party centres in the State or in the whole country, but as has been stated, the fulfilment of their decisions depends entirely upon the goodwill of the various national organisations; the Party bodies have no independent means of getting their decisions carried through.

Can such a system of Party organisation lead to the establishment of a centralised disciplined Party? Can such a Party work successfully among the nearly 30 millions of the working class in America?

Of course, in a polyglot country like America it is very difficult to establish a centralised Party, and it is very difficult to work among the numerous and varied elements which came to America from various countries, having different customs, and living in various stages of development. But in order that the Workers’ Party may become really capable of organising the working class and of leading it to the fight, it must be organised in such a manner that all the members of the Party, working in the same factory, irrespective of nationality, join the same factory nucleus. The district committees should be elected at conferences of representatives, of factory nuclei and street nuclei; the district conferences should elect delegates for the town conferences and the town conferences should elect delegates to the State conferences. The nuclei district committees, town committees and State committees should serve as Party organs for all the members of the Party irrespective of nationality.

From the reports contained in the Daily Worker of March 3rd, 1925, it appears that the few factory nuclei that have been formed work well, and that they have shown, not only that their existence is possible, but that it is absolutely necessary, for some of them have succeeded in organising great mass meetings of protest against the conviction of Sacco and Vanzetti, have conducted campaigns against child labour and have succeeded in getting their members elected to several local bodies of the Miners’ Union.

The nuclei should arrange their work in such a manner that the work be conducted among all the nationalities in the given factory. The district committees should establish agitation and propaganda departments to organise the work among the workers of all nationalities and for this purpose to enlist the services of all the active Party workers who formerly have been working in the various national organisations. The State and Central Committees of the Workers’ Party should also establish their agitation and propaganda departments for the purpose of guiding the work and getting it carried on among the workers of all nationalities and for this purpose enlisting the services of the comrades who formerly worked in the various national organisations. At the same time Lithuanian, Lettish, Finnish, Swedish, Russian, etc., members of the Party, who belong to various national non-Party organisations must form local and national fractions in these respective organisations. These fractions must work under the guidance of the district, town, State and Central Committees of the Workers’ Party respectively.

Only when the Party will be organised on this basis, will it become a fit and militant mass Party.

It will not be possible to bring about this re-organisation without some difficulty, but if the necessity is understood and the desire is there, the gradual re-organisation of the Party on this basis is quite possible.

Formerly, in America several trade unions were divided into national and language sections, for example, the Miners’ Union, but gradually this was abolished. The trade unions did not suffer as a result of this, but now have centralised leadership. If the trade unions managed to do this (and in this they were assisted by the Workers’ Party), it should be quite possible for the Workers’ Party to do so.

The Organising Department of the E.C.C.I. will devote very serious attention to the re-organisation of the Workers’ Party.

Conclusion.

The Conference on Organisation for the first time clearly brought out the state of Party organisation in the largest sections of the Communist International. The good and the bad sides of Party organisation were revealed. It was possible to clear up controversial questions and the harmfulness of various existing forms of organisation, as for example, the system of functionaries, the parallel existence of groups of ten organised according to place of residence and factory nuclei, the erroneous opinion regarding the superfluousness of organising fractions in opportunist trade unions, etc., were made clear.

The forms of organisation of Communist fractions were established. A resolution was passed on the work of the nuclei, the arrangement of the work of the nuclei and the attraction of the members of the nuclei to Party work.

A resolution was also passed on factory nucleus newspapers in which their good and bad sides were pointed out and indications given as to how they should be published in future.

The members of the Conference exchanged views with regard to the question as to how Party campaigns should be carried out. The established utility of linking up factory nuclei in a given industry with the factory nuclei in the same industry in other countries. Furthermore, the Conference on Organisation passed a set of model rules for various sections providing for the new form of Party organisation and also a set of instructions on the organisation of the Party apparatus from the nucleus right up to the Central Committee. The sections of the Communist International and local bodies will be able to apply these with advantage, allowances being made for local conditions.

The instructions, resolutions and that part of Comrade Zinoviev’s theses on Bolshevisation which refers to the question of organisation, will render it possible to introduce a uniform system of Party organisation in all the sections of the Communist International.

The fulfilment of the decisions of the Enlarged Plenum of the E.C.C.I. and of the Conference on Organisation wiil enable the Communist Parties to become real Bolshevik mass parties.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/new_series/v02-n11-1925-new-series-CI-grn-riaz.pdf