Sergei Tretyakov, a leading Soviet constructivist writer and editor of Pravda, later to be a victim of the Purges, with an essay on the marvelous German visual artist responsible for a Communist aesthetic in Wiemar Germany that continues to find many echoes in our own radical media a century later. On the Gestapo’s ‘most wanted’ list, the pioneer of the photomontage and anti-fascist, John Heartfield’s work adorned hundreds of Communist publications of the 1930s, among the most recognizable artistic statements of the era.

‘John Hartfield’ by Sergei Tretiakov from International Literature. No. 1. 1932.

What made him change his German name into an English one? Probably to avoid being mistaken for his brother, Wieland Hertzfeldt, the director of the radical publishing house, Malik-Verlag, that published the works of Seifulina, Gorky, Sholokhov and other Soviet writers.

It would be hard to find two brothers resembling each other as little as these. The publisher is an excellent business man. No one knows better then he how to pull wires, how to make clever moves in the publishing market, how to get round authors, get a deadly hold on the customers and melt the stony hearts of the wealthy.

The book-trade in Germany is quite unique. The windows of our book shops in Soviet Russia are crowded with hundreds, if not thousands, of books, while, there, they show three or four titles only.

The publisher only issues a book that is likely to become a best-seller. It must be brought to the notice of the reader by means of clamorous advertisements, it must be made indispensable, it must be on all book stalls, a fortune must be made on it.

It is no easy thing to make the public buy a book in Germany. Books are as dear as theater tickets.

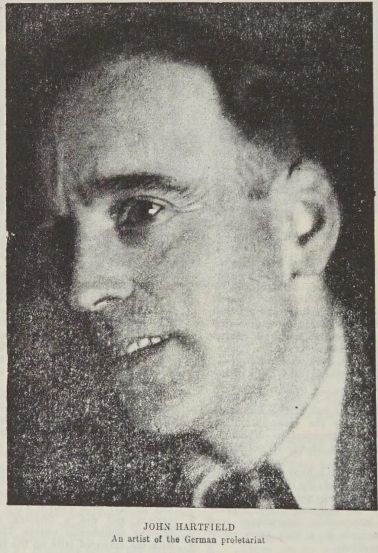

And here, in the private office of the prosperous director, equipped with a dictaphone, a telephone, by which orders can be given to any department by pressing one of the dozen of buttons, where even the sticking of stamps is mechanized and the typists worked like well drilled soldiers, I met John Hartfield. He looked very much like Buster Keaton.

He was very small, pale, serious. Apparently he had been accustomed to talk with people much taller than himself as he always held his nose rather high. His teeth and eyes were always visible to whoever happened to be talking to him, as a sign of trust and confidence.

His voice was low, very low, like the voices one hears in conversation when the train stops. In spite of a slight impediment in his speech, I knew that his voice could ring out with extraordinary clearness and distinctness from a big platform. When howls of dissatisfaction came from his audience he would throw out a few remarks with such absolute conviction that his enemies would listen with respect and his friends with confident pleasure.

The little man earned for himself the reputation of being “as honest as the sun,” “as clear as crystal,” “not to be bought,” “the most disciplined.”

“That’s the purest of all the Communists from among the intelligentsia in Germany,” was the opinion of both Party members and acquaintances.

Other epithets were added, it is true, such as for instance: “not of this world,” “impractical,” “exploited.”

Small people who whisper and have strong convictions are subject to rare but fierce outbursts of passion that nothing can withstand. Such fierceness and supernatural strength was concealed in this little Buster Keaton.

“Comrade Tretiakov, you’re quite right in what you say. We need clever art. The art that encumbers the markets, the museums, the theaters and the cinema is stupid art,” he whispers, either to the audience or to me: I have just finished my speech.

I agree.

“Yes, John Hartfield, we need clever art. But, the art we see around us is not so stupid as it seems to you. It is a clever art in its way, it carries out the work of making people stupid very cleverly.”

“Comrade Tretiakov, you are right. But it seems to me that an art that makes people stupid must be stupid itself.”

“You’re right, Comrade Hartfield.”

John Hartfield hates the world “artist.”

“I am a photo mounter, my trade is political photo mounting,” he says.

He took up this work in 1915 and 1916, while he was in the army. He served in the guards. Buster Keaton must always be eccentric.

A whispering chap about four feet high among the loud voiced giants of the guards. He looks consumptive, his movements are light and delicate. The most suitable type for a guardsman!

He attributes his not being thrown out of the guards for two and a half years to the fact that Hindenburg preferred small soldiers for long marches. They did not get out of breath so soon.

The division to which he belonged was waiting to be sent to the front from day to day. Every day, three hundred and sixty five times a year, the men were waiting, shuddering, prepared for the attack. Tomorrow out in the fighting line. But tomorrow would come and the attack would be put off for another day.

So the attack never came.

1919. The Revolution and the birth of the Communist party. Hartfield joined the party, with his brother and the artist Gross, whom he has never ceased to love even up to now, in spite of Gross’s anarchistic twistings and turnings.

From 1919 to 1921, John Hartfield, together with a group of militant communists published a magazine called Pleite, (The Crash).

The journal was devoted to satirical attacks on the bourgeoisie, which was then passing through one of the blackest periods of bankruptcy. The vigor of its assaults and the strength of the associations on which it was built, were reminiscent of our Soviet journal The Art of the Commune that came out about that time and for which Maiakovsky and Brik were partly responsible.

Pleite, however, lacked that wealth of theoretical work for which Art of the Commune had been notable and which provided material for theoretical work on art for the next ten years.

There was a short break and then Hartfield began in 1923 to work for a satirical journal Der. Knuppel, (The Baton. It would have been called Knout by us if it had been published in 1905.) He worked on this magazine until 1927.

Outside of this, Hartfield carried on poster work for the principal campaigns of the Communist Party.

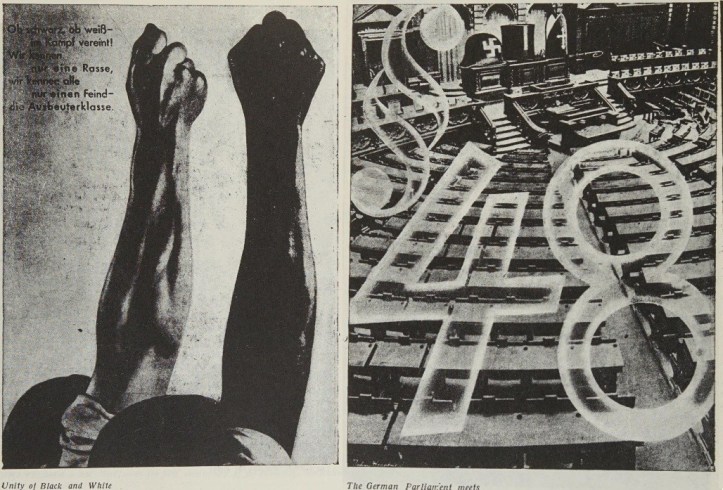

In 1923 the Union of Red Front Fighters was formed. Hartfield was requested by the Party to design a badge for the Union.

His design represented a threatening fist hanging over a crowd of people.

The sign of the fist came to be used by the Red Front Fighters on meeting each other.

The Municipal elections were held in 1925 and the communists came forward with their election list No. 5.

Hartfield: designed a poster with a hand, palm outwards, and the five fingers outspread—the fifth election list. This placard was so popular, he says, that the outspread palm became a gesture of greeting used by comrades during the election.

To design a striking poster or badge that would go straight to the mark in campaigns or Party work is very important and by no means easy in Germany. There is, perhaps, no other country where symbolic signs play such an important part as in Germany.

The list of badges and signs of various societies, political, tourist, musical, and research occupy from four to five pages in German almanacs.

Shops selling trimmings and haberdashery have special windows where nothing but emblems and badges are shown. Here you will find the Fascist swastika, the non-party lily of nature lovers, Roman Catholic crucifixes, patriotic eagles, and the red star of the Bolsheviks with the hammer and sickle.

The badges are worn in the buttonhole or cap.

As soon as Rote Fahne was founded Hartfield started to work for it as a cartoonist.

Germans remember his caricature of the social-democratic leaders. It showed a group of admirals on board a battleship, for which money had been voted by them.

But Hartfield’s great work is not drawing. He is at his best in photo mounting.

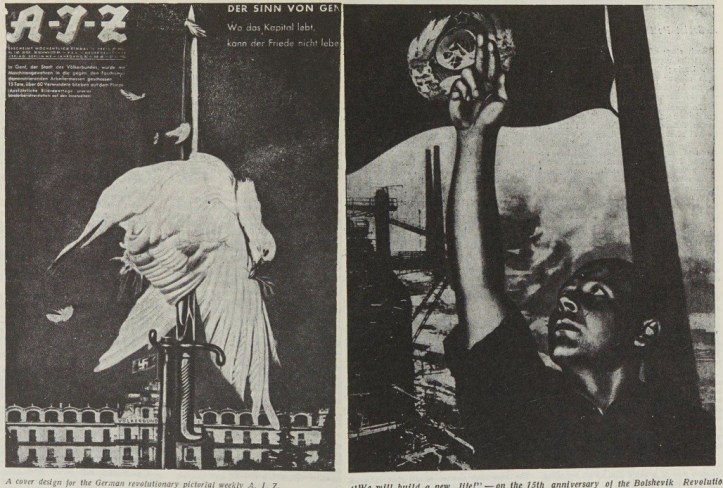

These can be seen regularly in AIZ (Workers Illustrated). The photo-mounting for the covers of the Malik-Verlag publications are particularly famous.

Starting with rather scrappy stuff, Hartfield has gradually perfected his technique and arrived at combinations of extreme simplicity, exceeding the usual trade and advertisement requirements for book covers.

His are not merely covers, they are posters, they are political, militant caricatures and political generalizations, made by means of photo mounting, in which the documental quality of photography assumes a special explosive force.

He showed me this work, and took out a whole heap of glossy book jackets, covered with photographs.

Here was Upton Sinclair’s Boston. The black shadow of the electric chair was cast on the blinding square of light left by the open door.

And here were actual photographs of sailors that mutinied, on the cover of Plivier’s Kaiser’s Coolies.

And here was a jacket for a book on espionage among the highest ranks of the German army. There was a fight with the censor about this jacket. A colonel of the Imperial Army, a prosperous officer of impeccable appearance, was shown in the photograph as a man gone slack sitting stroking a prostitute.

The censor demanded that the colonel’s hand should be removed from the prostitute’s leg. Hartfield cut it out in a square and printed on the white space—“Cut out by order of the military censor.” The censor suggested that these words be removed. Hartfield took them out, but substituted the demand of the censor with regard to the inscription.

Just lately he had some trouble about the jacket for Sinclair’s book Money Writes, which describes the corruption of writers and journalists. The figures of clerks and writers are shown bending. conscientiously over their work. Threads stretch from their writing hands to the upper margin, where they are gathered into the grasp of a fat, loathsome, be-ringed hand.

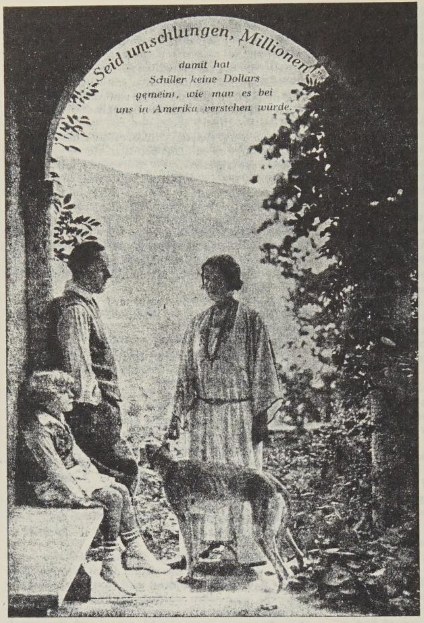

On the other side of the jacket a poetic landscape is seen, where a handsome young man with his collar open at the throat in a beautiful, Schiller-like manner, gazes down from a gay terrace over a lake. His wife and child and an expensive dog stand nearby. This is a family photograph of the world famous writer, Emil Ludwig, who was extremely popular in Germany. Ludwig began as a revolutionary and innovator. But he was soon bought over. He gave up innovations and did a thriving trade in Kitsch—fulsome sentimental novels. These novels bought him the splendid villa on the terrace of which he was photographed.

The writer in question turned out to be the materialized argument for the title, Money Writes.

Ludwig, however, would not suffer this affront. He brought it into court and the court ordered the publishers to make the photograph impersonal.

John Hartfield made it impersonal. He cut out the faces of the writer, his wife, child and the dog’s muzzle. These four white spaces were a slap in the face for the German censorship, and the novelist, beloved of the petty bourgeoisie.

John Hartfield never signs his posters and book jackets.

AIZ, Rote Fahne, the booklets published by “Malik” sell by hundreds of thousands all over Germany. But probably there are few outside the upper strata of the radical intelligentsia who know that these book jackets, powerful as a great political demonstration, are done by a little artist without a name.

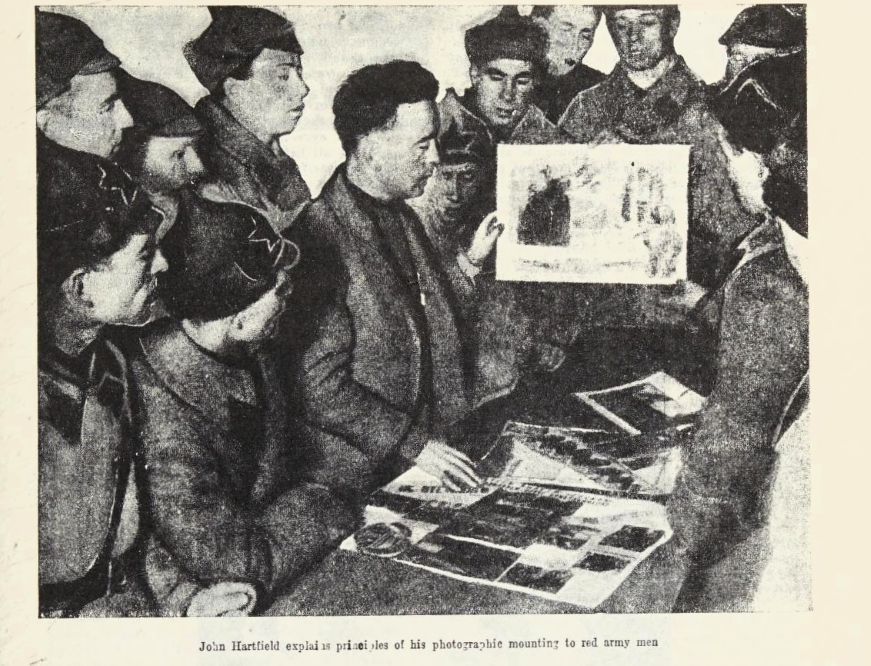

Thousands of our Soviet workers see the Workers’ Illustrated, enjoy the daring, expressive arrangement of photos in it, cut them out and use them for their wall newspapers—and never know that they are the creation of a small man with blue eyes and a soft voice, an implacable enemy of all capitalists, an iron German Bolshevik who goes by the English name of “John Hartfield.”

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1932-n01-IL.pdf