A central task of Marxist intellectuals in the early 1900s was to understand and explain the rise of imperialism. In this chapter taken from his ‘The Rise of the American Proletariat’ Austin Lewis looks at the United States in the 1890s and sees the culmination of a process begun in the Civil War.

‘Oligarchy and Imperialism’ by Austin Lewis from International Socialist Review. Vol. 7 No. 8. February, 1907.

More and more the literature of socialism in America is becoming an American socialist literature. It deals with American problems, draws its illustrations from American life and is in every sense of the word indigenous. The latest accession to this new class of works is a book by Austin Lewis on “The Rise of the American Proletarian.”

The introductory chapters give a general survey of the proletariat as a class. Its relation to industrial development and American progress are well described. Although this task has been done so many times before by socialist writers, seldom, if ever, has it been done in a more condensed and accurate manner.

The American proletariat can scarcely be said to have arisen as a distinct class until about the time of the War of 1812, and has grown into a prominent factor only since the Civil War. It is with this modern period, which he treats under the title of “Oligarchy and Imperialism” that Comrade Lewis is at his best. There is so much that is good in this chapter and it gives so good a general idea of the whole work that we reproduce the larger portion of it herewith.

Following the period just described, we come to another, in which the psychological tendencies of the newly developed, but speedily omnipotent commercial and industrial classes, made themselves apparent. Legislation, the administration of justice, and national policy very soon bore witness to the power of the new idea. The old faiths which had suffered grievously in the early part of that period which immediately succeeded the Civil War were attacked more fiercely, so that the merest remnants remained of that vigorous Americanism which had exercised so profound an influence over the youth of the country and which had been the very symbol of individual liberty and democracy in government. Internal politics on the legislative side responded rapidly to the new tendencies but not more rapidly than did the law courts, so that strange and hitherto unheard of applications of ancient legal remedies were employed in a fashion which left no doubt of the intention of the jurists to interpret the law in terms of the new conditions.

Never has the effect of the influence of economic facts upon legislative and judicial forms been more evident. Just as the industrial development in this country proceeded more rapidly than in others by virtue of the entire newness of the conditions and the freedom from artificial restraints, so the necessary legislation and legal decisions were more easily obtained here than elsewhere. The possession of the political machinery by the greater capitalists and the dependence of the judiciary upon politics gave the commercial revolutionists control of the avenues of expression. The capitalization of the press and its employment by the same agencies was another very important factor in bringing about the same result. Practically all the channels through which force could be employed were in the hands of this class at the beginning of this period and the ease with which success was achieved tends to show the thoroughness of the preparations which had been made to render it complete. It is not too much to say that in this period a revolution was accomplished which, for scope and magnitude, probably transcends any revolution of which we have knowledge. No merely political revolutions can be even compared with it. The industrial revolution which in the short space of twenty-five years converted England from a country in which the domestic industry was dominant to a modern machine-industry community is, probably, unless we except Japanese development, the only other instance of so sudden and complete a change. But it took many years for Great Britain to modify her political and juristic systems sufficiently to render them the best expressions of the new economic realities, whereas, it required but a very short time to convert the Senate into a body recognized as the supporter of the commercial and industrial lords and to make the House of Representatives but a large committee for the registering of decrees to carry out the mandates of the same masters. The government of the country was henceforward to be carried on in the name of those interests which were sufficiently powerful to set the machinery in motion.

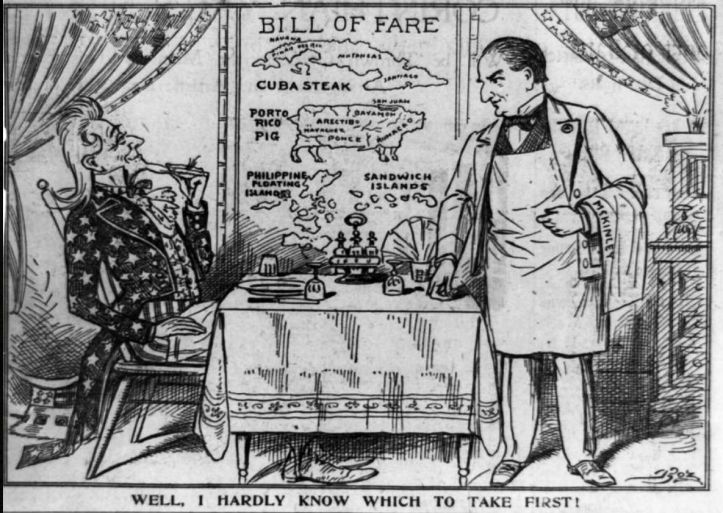

That collectivism which follows unavoidably in the train of concentration of industry did not show itself as a collectivism supposedly benefiting the whole community. State socialism to which this industrial development has given so great an impetus on the continent of Europe made but little headway here. Such collectivism as there was consisted in the collectivism of a class against society. The great capitalists pooled their interests and directed their united force to a campaign of public plunder. And when the amount of wealth produced under the new system bade fair to choke the channels of distribution in this country, the demands of the manufacturers and commercialists for foreign markets brought a new idea into American foreign politics. So that the country which had been hitherto self-contained and which had framed all its foreign policy upon the notion of its inviolability and independence and its freedom from the embroilments of foreign powers, leaped into the arena of international strife, and in a few weeks added an empire to its possessions and became a great modern imperial power, having subject under its sway so-called inferior peoples, who could never in the very nature of things become citizens of the Republic.

Crisis of 1893.

This new period began, appropriately enough, with a crisis, one of those inevitable breakdowns which serve, much as war does, to clear the air and to eliminate numbers of the unnecessary. The crisis of 1893 displayed itself in the first place as a financial crisis, though it was followed by an industrial collapse which showed plainly that unrestricted competition was still productive of its old effects, and that republican institutions and a high tariff afforded no security against those maladies which have so grievously afflicted the peoples of all modern countries.

***

The elimination of numbers of middlemen and small producers has always been the essential characteristic result of industrial disturbance. On the other hand the reinforcement of the working class by those better equipped who had fallen into its ranks owing to the action of the crisis and the feeling of rebellion engendered in the minds of numbers of the working class by their sufferings and privations tended more and more to the building up of a self-conscious working class movement. Just in proportion as the greater capitalism made greater progress than heretofore by reason of the crisis of 1893, the phenomenal growth in power of the proletariat was, at least, equally noticeable. The crisis of 1873 produced an active working class movement, that of 1893 stimulated and informed it. Defeated economically and compelled to submit to conditions against which it had contended with increasing spirit, its wages lowered, its organizations much depleted and in some cases disrupted, it still kept its aim before it, and at the conclusion of the depression was ready to take the field again and to enter upon a more vigorous campaign for its demands.

The working class is the one constant factor. It is not possible to dispose of it. The crushing of its members under the weight of exploitation only serves to amalgamate its forces as a pebble walk is solidified by tamping.. Such gains as it makes stimulate its ambitions, awaken its energies, and drive it to seek still further successes at the expense of its natural and implacable enemy. The two forces, the organized capitalists and the organized laborers must face one another on both the political and economic fields. The crisis of 1893 made the lines of the respective armies more distinct and showed to many of those who had not hitherto perceived what was impending, the real social and political significance of modern industrial life.

Coming of the Trust.

This period was marked by the growth of a new form of industrial organization which had had a very important effect upon the politics and commercial enterprise of the nation and which appears destined to be a still more important factor in future. This phenomenon is classed under the general name of “trusts” and although much condemnation has been directed against it, it appears to be as simple and logical a development of industry as any of the other forms with which industrial evolution has made us familiar.

***

This trust phenomenon is really a product of economic conditions since 1898, at which time the industrial depression which had set in with such intensity in 1893 subsided, and a period of buoyant optimism supervened, produced by a succession of good harvests and the popular enthusiasm and confidence which followed upon the termination of the Spanish War. The development of railroad industry had, up to this time, absorbed the bulk of invested capital, but the development and practically complete organization of the railroad stocks in very large quantities at low prices were no longer available. The field for investment of money, released by the feeling of security and the impetus given by the revival of prosperity, was discovered in industrials, and the energies of promoters were directed to the organization of industrial enterprise as outlets for capital seeking investment.

***

But while the organization of the trusts made undoubtedly for economic advantage, and while the balance was unquestionably in favor of the new system, there were other effects which were very disturbing. Thus the concentration of the almost incredibly large masses of capital rendered the existence of the smaller firms so precarious as to be practically hopeless, and the outcry which was raised by the sufferers found its expression in jeremiads in the press and in a helpless political indignation which exhausted itself in the cry, “Down with the Trusts,” but which was futile against the tremendous financial forces ranged on the side of the new organizations.

The Trist in Politics.

The rapid organization of such colossal industrial enterprises could not fail to have a most profound effect upon all departments of national life, and the corrupting power of great sums of money used without stint or compunction by those who had immediate pecuniary interests to serve was soon made evident. An era of corruption and debauchery set in much as had occurred subsequent to the Civil War, and the judiciary and the legislatures were exposed to the full force of the attack of corporate wealth. This descent of the trust organizers and controllers into politics was followed by results which do not reflect any credit upon the honesty and stability of legislative and judicial bodies in democratic communities where the standards are almost exclusively money standards, and where neither the social position nor the financial standing of those who are charged with the control of affairs is sufficient to support them against temptation.

The history of this period of prosperity is a long tale of official misconduct in almost every branch of governmental activity, municipal, state and national. An era of what is simply and cynically termed “graft” set in and the press teemed with revelations of official iniquity. Even the ordinary magazines made it a special point of detailing the operations by which the municipalities were robbed of their utilities, and showed to their own financial advantage and the interest of their purchasers the methods employed by industrial organizers in their efforts to make their organizations supreme. These revelations, while stimulating occasional outbursts of indignation and furnishing professors, clergymen and severely sober journals with opportunities for rhetorical and high flown denunciation, produced but little effect upon the community at large. They were regarded as natural and unavoidable concomitants of the system, and, in the general prosperity, were contemplated with equanimity. Now and again, an unusually bold piece of villainy would create a sensation, but, if the feelings engendered by such occurrences were analyzed, it would probably be discovered that admiration of the powers of the successful promoter was at least as marked as indignation against a public wrong.

***

The new industries fell into the hands of a diminishing group of men who exercised an increasing amount of power, the oligarchy which had been foreshadowed even before 1893, was fast being realized, and had become an accomplished fact.

Henceforward the political tendencies of governmental centralization were to be more strongly marked than hitherto. The individualism of the state system began to be a serious obstacle in the path of political and economic progress, and it became only a question of time when the more complete commercial and industrial organization would be mirrored in a more complete political organization. The centralization of industry must necessarily find an expression in the centralization of governmental power. The question thereupon arose, at least by inference, as to which of the governmental organs was to be the representative of this centralization. There are two departments of the government, each capable of fulfilling that function. The senate by its limited numbers, its recognized role as the representative of the power of organized wealth, and its vast political influence might serve as an active executive committee of the economically powerful; or the President by virtue of his position as the nominal head of the State might act in the same capacity. So there was outlined a struggle between the President and the Senate which has already shown signs of increasing intensity, and which may conceivably, within a very short period develop into the most important incident in the unfolding of American political history. The incongruity between a closely knit and highly organized economic system and a loosely connected bundle of individual states, any one of which may at any time seriously hamper and interfere with the economic organization, is so obvious that the permanence of the system cannot be seriously considered. The difficulty of course lies in so arranging the power of the units that the national economic system is not interfered with. But this becomes increasingly intricate in proportion as the development of industry transcends the limits of the individual states, and great enterprises come into existence whose ramifications and the extent of whose interests bring them into contact with the state legislatures at so many points. All sorts of impediments have arisen, therefore, to the development of the greater industry, but it, with a confidence born of security, has succeeded in using even these factors in its service, and by a discreet use of corruption funds ever increases its hold upon the various political systems of the individual states. This method is, however, costly, uncertain, and unsatisfactory, and therefore the cry for federal control arises, or for the federal supervision of transportation and other industries which overlap diverse sections of the community. Such “control” is under present circumstances a mere euphemism, for the economic forces are so far in control of the political that any claim on the part of the federal executive or the federal judiciary to exercise a controlling influence over its master savors rather of opera bouffe than of reality.

Expanding Capitalism.

An incident in the course of the development of this greater industry has been the establishment of a strong foreign policy, and the acquisition of territory outside and beyond the former limits of the country. The rapidly developing industry, the greater mutual dependence of the powers owing to the ramifications of business relations, and the jealousies and opportunities for strife engendered by the clash of the interests of the dominant national capitalists made it imperative upon the government of this country that it should have greater influence with foreign powers, and this, of necessity, rendered the construction of a sufficiently formidable navy essential.

The idea of a strong navy which would be employed outside the country met with much opposition from those Americans who still maintained the independence of this country of foreign embroilments, but a dispute with Great Britain with respect to the conduct of that power in Venezuela furnished an admirable argument to the advocates of the greater navy policy. The navy was needed to uphold the Monroe Doctrine, and is not the Monroe Doctrine as essentially American as free speech, a free press and liberty of contract? So the building of the new navy proceeded, and a new and very lucrative industry was founded for the private capitalists who built the ships on contract and caballed, intrigued, and corrupted to obtain these contracts on the best terms possible.

The profits on the building of the navy were absorbed by private firms. The opportunity of creating a great national shipbuilding plant was lost, and the country became dependent for its sole effective offensive arm upon a few great firms which in their turn were dependent upon or interested in the powerful steel interests. It must be remarked that the development of the steel industry and the organization of that industry which rendered possible the production of cheap steel were necessary conditions precedent to the building up of the new navy, and hence, in the last instance the national navy, became a product of and dependent upon a small but exceedingly powerful group of capitalists, who were now practically compelled to look for foreign markets for their surplus products.

The acquisition of the Philippine Islands gave these capitalists an immediate interest in affairs in the Orient which was now, under the leadership of Japan, showing signs of an awakening and is promised to be a fine field for commercial exploitation. A war between Japan and China, in the settlement of which the United States took an active part, was followed by a rising against foreigners in China and by massacre and pillage at the hands of a certain sect of fanatics termed “Boxers.” This rising led to the active interference of the leading western powers for the purpose of securing peace, and the United States co-operated with these powers in the employment of troops in the land of another people thousands of miles away. Since that time difficulties with outside foreign powers have been not infrequent Turkey, Germany, San Domingo and Morocco have all had disputes with this country.

***

However, the entry of the United States into the group of great nationalities, whose commercialists and manufacturers are engaged in active competition for the possession of the world’s markets, is now an assured fact. The demand for a stronger navy still continues and the demand for a greater army to keep pace with the navy is made with much insistence.

***

There are signs also that the same increase in the military forces may be directed against the possibility of civil discord arising from the eternal labor troubles.

There is a still more evident growth of the idea that the chief object of American foreign policy is to secure the best markets for American products and to advance the interests of industrial and financial magnates. All of these phenomena point to the influence of the trader and manufacturer in politics and show that the mainsprings of the international policy of the United States are to be sought in the interests of the greater capitalism.

***

It cannot be forgotten, moreover, that the country by its rapid development of its wealth producing resources no longer occupies the subordinate economic position which it once held. It is no longer dependent upon capital from the outside. The growth of the syndicates in strength and influence has rendered the funds at the disposal of the lords of finance much more accessible than hitherto. The preponderance of wealth gives this government a growing influence which is only prevented from making itself still more apparent by the lack of organization of its military resources upon anything like the same scale as has been accomplished in European countries. How far this military organization will be discovered to be necessary is a question at once suggested by the occupation of the Philippine Islands whose proximity to Asia and consequently to the very center of international rivalry has drawn the United States willy nilly into the struggles of the Powers. That the commercial interests of this country are estimated to be very closely bound up with the development of the Orient is obvious from the anxiety displayed by the government with reference to interference in the Chinese troubles, in spite of the denunciations of those American statesmen and journalists who regarded the movement as being on the one hand a departure from traditional policy and on the other as involving possibilities which it would be the part of the discreet to avoid.

Coxey’s Army.

The crisis of 1893 produced strange psychological aberrations in certain sections of the working class as well as in that portion of the debtor and farming class which saw in free silver and the populist platform the solution of their troubles. The latter propaganda was attended with a fanatical devotion as unusual as it was ridiculous. A sort of semi-religious, semi-hysterical socialism not unlike that which had manifested itself on the continent of Europe, in France particularly, in the early forties made itself evident, and the “Burning Words” of Lammenais were re-echoed more or less feebly, on this side of the Atlantic by impassioned advocates of the new doctrine. But beside the mortgaged farmers, there was a great mass of unemployed which suffered privation owing to the dislocation of trade. Impatience with their lot grew more and more marked among the inhabitants of the West, whose frontier life had made them more disinclined to submission than their eastern fellows. The attacks of the free silver preachers had impressed upon the popular imagination that the government was to blame. Therefore they determined to display their poverty to the government Hence arose the memorable exodus from the West to the East which was popularly known as the march of Coxey’s army.

***

As a dramatic exhibition of the poverty of the unemployed it was a complete failure and can only be considered as an example of the vagaries which haunt men’s minds in times of economic stress, a species of hysteria produced by their desperate circumstances, and liable, under extreme conditions, to produce strange and even terrible results.

[Another feature of this stage was a series of fierce industrial conflicts, especially the AR.U. strike, and the Coeur d’Alene struggle which gave rise to a greater extension of Federal power and the introduction of new weapons, particularly the injunction.—Ed.]

Effect on the Working Class.

But this conflict between the labor organizations and the greater capitalism did not have that invigorating effect upon the former which might have been reasonably expected. On the other hand, the oligarchy which swayed the political and business world mirrored itself in the labor organizations. The tendency which was noted in the previous decade persisted and developed itself even more strongly. The depression in trade which filled so large a portion of this period had caused the trades organizations to show a marked falling off in power and influence. Such is always the effect of economic crises and hard times. The recurrence of industrial prosperity, on the other hand, showed itself in a wonderful growth in the trades unions. But it is undeniable that this activity in trades union circles produced no adequate effect upon the position of the working class. The share of product which went to the laborer ever diminished. The liberties taken by the courts and the military, as already described, showed that the influence exerted by the laboring class upon the government was of the slightest and that their enormous numerical strength was more than offset by the wealth of the dominant class.

The reasons for this condition of things appear to lie in the characteristics of the American labor movement as it had been developed in the course of the economic evolution of the country. There had been from the beginning, as in England, to a very great extent, a failure on the part of the union leaders to grasp the significance of the struggle in which they were involved. The failure to see the significance of the labor movement resulted in the precipitation of conflicts in which the working class was confronted with the certainty of defeat. Issues also upon which a straight and uncompromising fight between the opposing classes might have been successfully waged were shirked. Thus much needless suffering was inflicted and slight enthusiasm engendered.

The fact was that the trades leaders, even the best informed of them, were continually haunted by the notion of contract. The two necessary factors of production were in their estimation placed in juxtaposition, in eternal antithesis like the ends of a see saw. One, however, could not gain any permanent advantage over the other. The individual capitalist was considered by them to be necessary to the existence of the workingman. They, even the strongest of them, were thus deprived of the enthusiasm and confidence which a grasp of the class war would have given them. Without this support their policy was wavering, indecisive and, though of temporary value, in a few trades, only efficacious up to a certain point, and impotent to prevent the returns to labor continually diminishing in ratio to the growth in wealth and the increase in the amount of invested capital.

Besides, the prospects of reward held out by the political managers of the greater capitalism to successful labor leaders had filled some of the most ambitious and capable with the resolution of gaining place and position for themselves independent of the advancement of the generality of the class to which they belonged. Many labor leaders became little better than freebooters, selling their followers in the interest of rival capitalists, turning from this side to that in the war which rival capitalistic concerns waged against each other, according to the price offered for their services. They were mere condottieri selling their modern equivalent of the sword, the power of organizing and leading men, to the highest bidder. A brisk trade was done in union labels and other devices of a similar character. Blackmail was levied. In fact, in the very ranks of labor itself there was a group of corrupt manipulators whose nefarious activities may be compared with those of the fraudulent army contractors operating in the Spanish War.

It became more and more evident that the morals of the dominant capitalism were finding their reflection in all sections of the community. A period of apathy m the ranks of labor naturally supervened. Strikes and lockouts were, of course, as common as before; the struggle, inevitable in the very nature of things, continued. But local and sectional influences were stronger than the general impulse. The ill-regulated and ignorant, but at the same time generous, enthusiasm of the 80’s had waned, and the all-pervading cynicism which had greeted the victories of the Spanish War with a perceptible sneer in spite of the official applause found its counterpart in the attitude of the masses of the laboring elapses. Though the numbers of men enrolled in the unions grew with wonderful rapidity in the period of revived prosperity, there was none of that early abandon of belief in the power of the working class which had marked the earlier phases of the trades union movement. Leaders were stronger than ever before, the paper force of the organizations was greater, but the spirit was lacking. The crushing weight of the triumphant oligarchy weighed down the hopes of the toilers. On the one hand, their great industrial lords held arrogant sway, and then bulwarks of American liberty fell before them so easily, so bewilderingly easily that the masses of the toilers educated in the public schools to an absolute belief in the stability of the institutions of the country felt hopeless in face of the aggressions. On the other hand, the small bourgeoisie which was as much opposed economically to the advance of the oligarchy as the working class itself was bankrupt in character as well as in purse. Noisy demagogues with a talent for advertisement but with no ability for leadership occasionally appeared but succumbed to the money force of the oligarchy or wearied the ears of the populace with incoherent and useless complainings. The working class itself was devoid both of leadership and of enthusiasm. The oligarchy was in complete and almost undisputed possession of the field.

Though the official representative of the laboring class, the trades union movement, was in such a deplorable condition, the class war still found its exponents in the socialist movement. It was then in its incipient stage. With the progress of the decade under consideration it developed both in numbers and in the virility and definiteness of its propaganda. The increase in its voting strength was marked. Thus from a vote of a little over two thousand in 1888 it attained a vote of nearly forty thousand in 1896. But the progress of the movement was actually much greater than appears from the consideration of the mere vote. Organization had been effected, speakers trained, an English press established and vast amounts of literature, largely translations from the socialist literature of the continent of Europe, widely distributed.

Thus in the very hour of triumph of the greater capitalism the enemy was developing its strength. Small and numerically insignificant as it was the capitalistic forces were not slow to recognize its potentialities. The press teemed with attacks upon the socialists and the pulpit, ever the ready servant of tyranny, supplemented the efforts of the press. Such is the free advertisement which the spirit presiding over the progress of humanity always provides and, in proportion as the attacks were absurd in their violence, the interest of the public increased, and socialism, instead of being considered as an amiable weakness to which emotional people and raw foreigners were particularly prone, received very general recognition. This does not imply that there was any particular grasp or understanding of the socialist movement. On the contrary, the views advanced both by advocates and opponents were at this particular period more marked by crudity and feeling than by knowledge and perception. Still the point had been reached when socialism could be discussed, as, at least, a possibility. Thus both socialists and their opponents began to speculate upon a time when the laboring class, tired of the insolence of the oligarchy and the incompetence of the trades union movement, might direct its attention to the new propaganda.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue:https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v07n08-feb-1907-ISR-gog-Harv.pdf