There is no education like a picket line. Myra Page brings us into the Monongahela River community of Brownsville on strike as part of the National Miners Union-led fight in the Pennsylvania coal fields abandoned by the U.M.W.A.

‘On the Picket Line’ by Myra Page from New Masses. Vol. 7 No. 2. July, 1931.

Three miners and I—trudge silently down the dark winding highway. Around us loom the rolling hills of southwestern Pennsylvania. Ahead, huddled beneath the soaring slate dump stand row on row of company shacks, brooding in the night. Occasionally, some distance up the road, there is a flare of flashlights.

“Yellow dogs,” Mike whispers sourly. Yellow dogs, the miners’ epithet for Pinchot’s state troopers, coal and iron police, and company deputies.

In front walks Alec, jimminy-jawed veteran of many strikes, with him is his 18 year-old George who’d joined the union last April and done his bit since then lining up the other young fellows. Mike and I follow behind. Local organizer for this section, he reminds me of a southern pine tree with his upright, weighty trunk and long arms that hang like branches on either side. Like a pine tree too is his quiet strength that no winds of battle, can uproot. In the mines since a boy of thirteen he’d been chosen last year by the men here as their leader.

We are headed for Vesta Mine number–, which lies on the Monongahela river in the Brownsville area. This is the last lap of an eighteen-hour day. A day which had begun with picket duty at four-thirty, followed by local mass and strike executive meetings, a fifty mile trip into Pittsburg in a ramshackle car for the weekly district strike conference, and ending with the trip back. As a precaution we had left our driver up the road, and are covering the last stretch on foot. These men, as miners, know no fear. But union orders are union orders. They’ve been told not to get arrested unnecessarily. Forces are all too few. Many men and women are already behind the bars, on one pretext or another.

The men’s feet are swollen and blistered from so much tramping. They have had only one sandwich all day. One sandwich for eighteen hours’ strenuous activity. In four hours’ time the next round will begin. Maybe tomorrow, there will be nothing to eat. And there is an extra ten-mile march over to Vesta Mine number planned, to pull her down.

These things the miners accept as a matter of course. This is their strike, and they are out to win at no matter what cost.

Tonight they feel pretty good. Reports from other mine delegates throughout western Pennsylvania at today’s conference had been generally satisfactory. Many new mines are sending word, “Come, pull us out.” Walk-outs are spreading fast in West Virginia and Ohio. Yep, in spite of all the operators and U.M.W. can do, things look pretty good.

The two in front halted. “Where we turn off. S’long. See you at four-thirty.”

“For Christ’s sake don’t be late,” Mike whispers hoarsely.

“Hell no. Gotta keep out the rest tomorrow.” They disappear up a by-path.

Soon we circle in the opposite direction, coming out finally in front of a shack which stands on private land across the road from the “patch,” (company village). Pete—— , who occupies it with his wife and five children, has been blacklisted since the 1927 strike and turned out of the patch. He rents this from a small independent shopkeeper for seven dollars a month, tries to keep his family by doing odd jobs at carpentry work.

When the National Miners’ Union came into the field Pete was one of the first to begin agitating at Vesta, and signing up the men in “our own union.”

Mike knocks at the door. There is no answer. After a bit he knocks again, softly. A shuffling of bare feet on the boards inside. “Who’s there?” “It’s me, Mike, and a comrade.” The bolt slips back, we walk inside. The bolt thrown again, the lamp is lit and we take seats around the rough wooden table. The room is bare, except for a coal-burning cook stove standing at one side, the table and benches, and a row of shelves which Pete had built—conspicuously empty now but for a few dishes and a stack of the Daily Worker and Slavic papers. From each end of the room there runs a small bedroom which I later learn contains two beds each. There are no chests or closets, and no need for them, as the few pieces which the family have besides those on their backs can easily hang on the five nails along the walls.

The one-story shack is built of flat boards, with no plastering, or means of heat or light other than the cook stove and lamp. All water is obtained from one of the three pumps on the patch. Three out-houses serve twelve families.

Pete’s place was typical of miners’ shacks, though some are smaller and those on the patch are often two-story two-family affairs.

Everywhere I am again struck by the similarity between the miners’ plight and that of southern textile workers—both the primitive conditions under which they are forced to live, and the companies’ ruthless domination of every phase of their existence, mental as well as physical.

Coal-miners figure that their standard of living has been cut by seventy percent since the war, through wage-cuts, cheating at the tipple, and part-time employment. Meanwhile hours have lengthened to nine and ten, often for seven days a week (when there’s work). Close to two hundred thousand men and their families have been driven out of the industry all together.

There is one equally striking difference, however. While southern millhands have little or no organizational experience and are therefore largely puppets in the hands of their employers, the coal miners have more than thirty years of union struggles to their credit and a tradition of solidarity and defiant militancy that has no equal in this country.

Late as it is, we sit for a half-hour discussing the latest developments in the strike. There is an angry twinkle in Pete’s eyes as he tells us, “Yellow-dog ask me this morning, ‘What you do on picket-line? You no miner!”

Mike’s answer comes slowly. “You tell those sons of bitches that you got as much right as anybody on picket line. You tell ’em that when this strike is won, you’re going back to the mine.” “Sure,” Pete tosses his shaggy head. “I told ’em.”

Rosie, Pete’s wife who barely reaches to his elbow, breaks in. “Today yellow-dog tell me, ‘If you and your man don’t quit trouble-making, we stop your getting water at the pump.’ So I tell him, “We no quit. We get water from river. Good as your dam water any day.”

We turn in, Rosie, her youngest and my self in one bed, her four others \in a bed alongside. The men and another visitor sleep across the way. Grown-ups sleep in their clothes, only shedding shoes and maybe their top garment. Children bunch together naked, tossing and moaning in their sleep from long-felt hunger. Windows are made so they can not be opened, and as no-one dared leave a door open now that the dicks were breaking in, shooting and thugging in the night, the seven of us slept in a six by eight space shut up tight as a box.

Yet I never slept better than now, and on the nights following. I don’t think a sledge hammer could have robbed me and the others of those few precious hours of exhausted slumber.

Four o’clock comes all too soon. Heavy-headed, we swallow some hot water and make for the picket line. Pete has his saws wrapped in newspaper under his arm. After picket duty hell go over the mountain and do a day’s work. He curses over it, but he can’t stay off now, not with his kids starving, another baby on the way and but five months when he’s a chance for a few days work here and there. Last year, he tells me, he only made seven hundred. He carries no lunch bucket. What there is must go for the missy and the kids.

Heavy mists veil the hills and valley, and send a chill through our bodies as we march, two by two, up and down over a half-mile stretch on the public high-way before the mine’s two entrances. Gradually other figures emerge from the mist. The shabby line of men, women and children lengthens. Two hundred—three hundred—four hundred. Truckloads join us from neighboring mines.

Vesta has been struck only five days and needs help to pull the last 130 men out. There are nods, sallies. On the whole the march is a silent one.

Pete and Mike grin. By tomorrow the mine’ll be shut tight.

The first pickets carry an American flag. This is an old tradition. Furthermore, the pickets think it may keep the yellow-dogs from being quite so nasty. The flag shows they’re not damn bolsheviks and foreigners marching, but good citizens, fighting for bread. Some don’t care what the papers call them, but the majority do. A good proportion of the marchers are American-born, both Negro and white, and the younger generation of foreign-born parents who’ve come into the mines in the last decade. Many unemployed miners are also in line.

Company officials and Pinchot’s state troopers are worried. Never before have they seen so many native and foreign born, Negro and white, of all ages and both sexes striking and marching shoulder to shoulder. “Damn it,” one exclaims, “they’ll be trying to run the country next!”

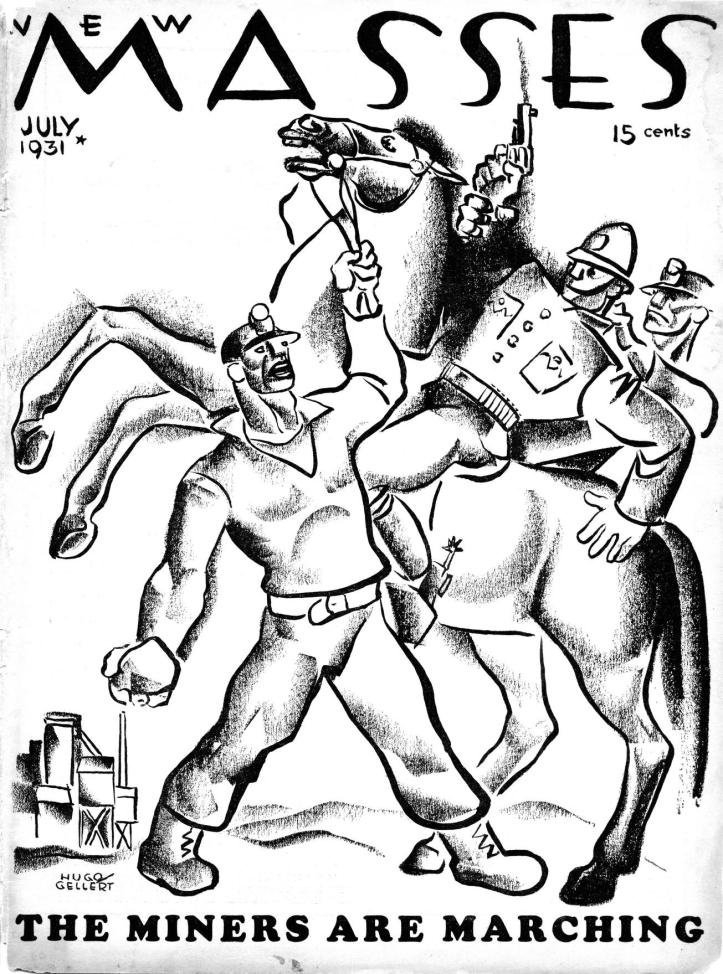

State police on prancing black horses race up and down, scowling and threatening. There’s a rifle across each saddle, a pistol and gas bomb at each belt. Their brutality and scabbing activities have turned the bulk of the miners against Pinchot. “We voted for him last time. He talked soft. But we’ll run him out of office yet, him and his state police.”

Coal and iron police guard the entrance to the company patch. They have blocked off a section of the public highway and announce it as “private property” in order to keep union men away from those still working. It means those who live in non-company houses have to walk the tracks to come to picket and mass meetings. In a day or so railway dicks will be arresting miners for trespassing on its private property. “By gorry, when that starts,” the pickets exclaim to one another, “there’s gonna be trouble. We ain’t after trouble, but if it comes–. Those yellow dogs ain’t got no right to fence off a public highway. What’s it coming to? We’ll just bust through. We know our rights!”

Five-thirty—six o’clock. Shrill blasts of a mine whistle calling to work. It’s the same whistle that has announced many accidents at the mine, in the past.

The marchers grow sarcastic. “Say, Mike, can’t you hear the whistle. Ain’t you working today?” “Say, Alec, where’s your bucket? How come you ain’t in pit clothes.” (Incidentally, many miner pickets are, for the simple reason that these coal-and greasestained garments, pit boots and caps are the last clothes they have).

Three miners from the patch, guarded by yellow-dogs, start hurriedly across the trestle for the mine. Shouts, growls. “Heigh, fellow-miners, don’t you know there’s a strike on here?”

One woman screams shrilly, “What you go to work for? You ain’t got nothing in your bucket no how!” This brings a general laugh, it’s probably the grim truth. For months past many miners have had only water in their buckets, or at most a piece of dry bread. And at the shacks they left there is also only bread, “and dam scarce o’ that.” The miners’ slogan which they themselves coined, “Strike—Fight against Starvation!” springs directly from their experience.

A few more men cross the bridge. Two car-loads tear through. The shouts grow louder, rougher. Someone throws a rock. “Ain’t you shamed,” the youngsters yell, to go to work, and take food from hungry children!” “My dad’s striking, why ain’t you?” A trooper swings across his horse at them. “Shut up, you, or I’ll send you off the road.” They know the men (except professional scabs) can’t stand out against the women and children calling them. The strikers snarl back. “We don’t want trouble, but…” The strike is young here, but company and police terror in past strikes and in many mines in the present one has taught Vesta men what to expect.

Over in the patch we see close to a hundred men and their families standing watching. “They won’t go to work, but they’re a-scared to picket,” the marchers comment. “Come on,” they call to them, “Don’t be scared. Join us.” No one moves. Later, when we hold our mass meeting in an empty field, large numbers from the patch attend.

New men and women are elected to serve on the broadened strike committee. Later in the day the women organize their Union Auxiliary, fifty kids form a Miners’ Children’s Club. Fervor runs high. The afternoon picket line sees practically every man, woman and child from Vesta on the march. Twelve hundred in all. The sun scorches down on us, the asphalt burns under our sore feet. But everyone grins, shouts, and the children’s section keeps up a continual racket.

That night forty eviction notices are posted in the patch, and many houses are entered by company dicks. The morning picket is not so long, but only a handful of scabs get through. The patch is on hand for the mass meeting.

Slim, a mountaineer type throws down his coat, and shakes his fist over his head. “Any man what’ll stand by and see his children starving and do nothing is a low-down.” Pointing upward he cries, “God above owes us a living.” In the next breath, shaking aloft a Daily Worker he cries in the same voice, “Miners, here, read this, the workingman’s Bible.”

To some extent Slim is typical of the change going on among hundreds of striking miners. “We’re agin Lewis and the operators and ’ll go down fighting for our National Union.” But they frequently add, “we ain’t Bolshies or nothing like that.” “We ain’t red, but our blood’s red,” others declare. A considerable and growing number state. “Sure I’m red. Red’s what the bosses don’t like. But it’s good for the miner and working man.”

Whatever their political beliefs, the 40,000 miners and their wives and children now striking in Western Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio under the banner of the National Miners’ Union, are consciously following its leadership. Even government investigators have admitted this. The miners feel this is their own union. It is they who are building and running it.

The possibilities of the situation are tremendous. It is probably the turning point in the history of American labor. Crippled by their misleaders for the last decade and more, coal-diggers are now coming back—this time under leadership they can trust. They say grimly: “It’s better to die fighting than starve to death.”

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1931/v07n02-jul-1931-New-Masses.pdf