In this superlative essay, Olgin, by looking at the post-war, post-Versailles international conferences at Locarno and Geneva gives a picture of international class relations of the mid-1920s and the position of the Soviet Union during the N.E.P. period.

‘Locarno–Geneva–Moscow’ by Moissaye J. Olgin from Workers Monthly. Vol. Vol. 5 No. 7. May, 1926.

OF all the post-Versailles international agreements, the pact of Locarno was declared to be the most important and most fruitful. Bourgeois and Socialist alike hailed it as the beginning of new humane relations among peoples and nations.

The Formal Content of the Locarno Pacts.

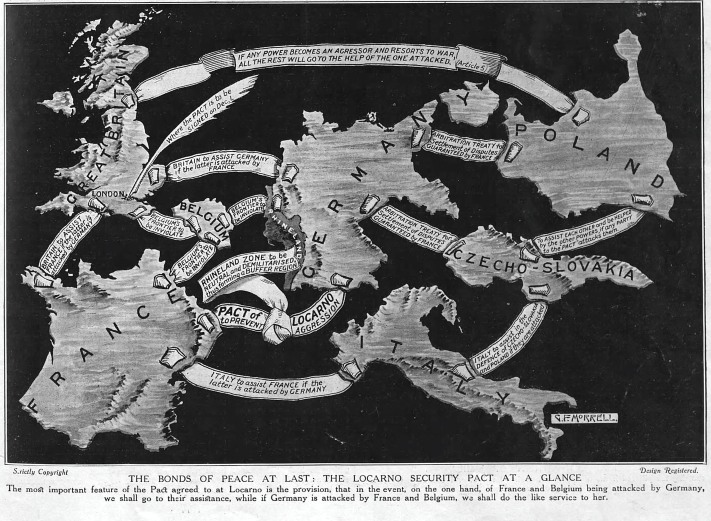

Formally, the pact of Locarno was a guarantee of mutual non-aggression between Germany and France. Both “high contracting powers” solemnly promised “that they will in no case attack or invade each other or resort to war against each other.” Germany promised, besides, not to amass military forces within the demilitarized zone stretching over fifty miles from the French frontier. The two traditional enemies made a high sounding declaration of mutual respect and friendship. Germany gave her definite “moral” consent to the loss of Alsace-Lorraine; on the other hand, France left Germany a legal loophole of raising in due time the question of upper Silesia and the redoubtable Polish corridor. But this was “music of the future.” For the present, the French and German governments guaranteed peace and good will. And, as is the case among highway and business men, a tangible security was required to back up the contracts. England was chosen the “impartial chairman” to decide what constitutes an “unprovoked act of aggression” and to rush to the aid of that power which, in the judgement of England, suffered injustice. Simultaneously, an agreement was concluded between France and Poland according to which France was to aid Poland in case of foreign aggression even if the Council of the League of Nations failed to find cause for the league’s intervention. In order to show that Germany in actuality becomes a responsible member of the “family of nations,” bearing both rights and duties before “civilized humanity,” Germany was to be admitted into the League of Nations with a permanent seat in its council, sharing this privilege with England, France, Italy and Japan.

The Real Motives Behind Locarno.

Formally, it was a question of “peace,” “cooperation” and “a new era of mutual confidence.” Behind formal outward verbiage, however, there were hidden vital economic and political interests of the various capitalist states.

1. Locarno and Germany.

It was impossible that Germany should not realize the disadvantages flowing for her from the pact of Locarno. The agreement left the Versailles treaty in full force. Paragraph six of the Locarno agreement said explicitly that “the provisions of the present treaty do not affect the rights and obligations of the high contracting parties under the treaty of Versailles or under arrangements supplementary thereto” (Dawes’ Plan). The Locarno pact left intact not only the atrocious, economically impossible payments to be made by Germany according to the Versailles treaty and the Dawes’ Plan which have actually rendered the masses of the German people serfs of the former Allies, but also the political provisions of Versailles which make it possible for France to march into German territory in case of non-fulfillment of obligations (as took place, for example, in the occupation of the Ruhr early in 1923). In other words, the Locarno pact drew Germany into the League of Nations to help the aims of the former Allies who offered Germany nothing in return outside of vague promises of goodwill. The pact of Locarno did not even guarantee the integrity of German territory in case of war between Poland and a third power, as it is obvious from that agreement that in such case France would send her troops thru Germany to aid Poland. On the other hand, the lessening of the military occupation in the German Rhine provinces and other regions as promised in Locarno, remained for the most part in the realm of words. It seemed that Germany lost much, gaining nothing at Locarno.

There was, however, one thing to which German capitalists looked with great eagerness as a possible result of Locarno, and that is foreign loans. Without foreign loans, German capitalism is no longer able to exist. In the one year of 1925, when the Dawes’ Plan was in operation, Germany had to pay to the victors 1 billion gold marks, but at the same time it received a foreign loan of 800 million floated in New York and London. This year, the sum to be paid by Germany amounts to 1.2 billion gold marks; for the coming year the payments are 1.75 billion; for the following year, 2.5 billion, and so on. The Dawes Plan has been in operation for only one full year and already Germany is in the throes of a grave economic crisis which springs not from accidental causes but is inherent in the very internal and external situation of German capitalism—outworn and antiquated machinery, deterioration of the entire technical apparatus in consequence of the war and after-war situations, backwardness of the methods of production in agriculture, inadequacy of the railroads, but mainly the diminished purchasing power of the masses of the population who, earning less than in former years, are forced to consume less. In order to be able to meet the payments flowing from the Dawes’ Plan, Germany must produce more and export more. In order to be able to meet the competition of other countries in the world market and at the same time retain the level of capitalist profits, she must increase the work-day and decrease wages. In order to continue in the present disastrous course, German capitalism would not hesitate further to lower the workers’ standards of living, if it were not for the fact that there is a limit to the patience of the working masses, especially in times like the present, when the number of unemployed has reached two million. To maintain its power over disorganized and disgruntled Germany, where workers, peasants and the lower strata of the so-called white collar proletariat are becoming more and more restless, the German bourgeoisie must look to the other countries for favors in the form of loans which would enable it to improve the industrial apparatus and temporarily to prevent a revolt of the masses. It is because of the need of stabilizing one of the very important capitalist countries that the Allies held out to Germany the promise of loans. In Locarno, German capitalists once more sold German independence, harnessing themselves, as they did, to the chariot of French and British imperialism, for at least a temporary staving-off of the great debacle.

2. Locarno and France.

It was also not for humanitarian reasons but for political and economic advantages that France agreed to the pact of Locarno. Like the slave holder whom it pays to send a physician to attend to his sick slave in order to save his working power, so France is interested in maintaining the miserable “stabilization” of Germany in order to save the payments accruing to her according to the Dawes’ Plan. On the other hand, France is waging a severe and exasperating war against the Riffs in Africa and the Druses in Asia, which makes it imperative for French capitalism to pursue a more peaceful policy on the Rhine. There is, besides, the tendency to combine the French ores of Alsace-Lorraine with the German coal of the Ruhr and the Saar in order to form one powerful industrial combination.

Above all, however, France needed the Locarno agreement to calm her own masses by a propaganda of peace and- he promise of a “new renaissance.” France, the victor, the hetman of Europe, the power that has gained more than any one of its former allies from the peace of Versailles, is in no position to overcome a permanent internal crisis. France is practically bankrupt. Interest on domestic loans eat up nearly half of the yearly budget which has mounted to the height of 33 billion francs. Interests on loans owing to the United States are hardly being paid. Armaments and wars sap the vitality of the country. The franc is continually depreciating. The political situation is far from secure, one cabinet crisis following another. This year it was entirely impossible either to balance the budget or to pay 10 billion francs on domestic loans due December 8, 1925. The large bankers and manufacturers, of course, are not the sufferers under such conditions, but the situation of the petty bourgeoisie, the farmers, and the city workers becomes more and more difficult. It was to approach those masses with a promise of peace and prosperity that the Locarno pact was particularly needed by French capitalism.

3. Locarno and England.

Locarno was no less needed for English “capitalism, which in the past war period had begun to view with anxiety France’s growing strength in Europe, the French alliance with Poland, her influence over the Little Entente, the occupation of the Ruhr, and the manipulations of French militarists in other German regions. For England, the pact of Locarno was a means of thwarting France on the European continent. The delicate situation of France, immersed in war-with colonial rebels, made it possible for England to secure a strong position thru the Locarno treaty—that of an “arbitrator” who, in case of war between Germany and France, is free to throw all his weight on the side of that power he would declare aggressor. The pact of Locarno made possible the outlook of a German-English rapprochement within the League of Nations as a menace to the Franco-Polish, Franco-Roumanian and other French alliances.

On the other hand, England was no less than France interested in influencing her own proletarian masses. There is no longer any “peace and prosperity” within the British Isles. Postwar England is no more the leading power of the world, as evidenced by her balance of trade, which fell from 153 million pounds in 1923 to 63 million in 1924 and to 28 million in 1925. England is ceasing to be not only the banker, but also the manufacturer of the world. The British dominions, the colonial and semi-colonial countries are developing their own capitalisms. The American manufacturer and the American banker are successfully competing with England both in the goods of the world and in the world of finance. The collapse of the empire looms up as a not very distant possibility. In the meantime, interests on internal loans amount to 1.5 billion dollars yearly, excluding payments on American loans; the army of unemployed remains above 1.5 million, rising some times to more menacing proportions; the labor movement is becoming more radical and saturated with hatred for the capitalist system; the friendship between the English and Russian trade unions has become a fact, as is also the growing influence of the U.S.S.R. over India and the other colonies.

To combat the wave of unrest rising in England, the pact of Locarno had to be contrived. The prospect of a “pacified” and “united” Europe, of an increased English influence in European affairs, i.e., of an increased market for the English capitalists, the prospect of abolishing English military occupations of Cologne, etc., would have made it possible for the English bourgeoisie to demand of the labor leaders more “co-operation,” to demand of the workers more efforts “to improve general conditions,” fewer strikes, fewer demonstrations and protests, more “confidence” in the capitalist system, etc.

4. Locarno and Capitalist Stabilization.

If it is thus evident that behind the pact of Locarno there were clearly defined specific interests of the capitalist groups dominating the governments of England, Germany and France (the roles of Italy, Poland and Belgium were of much lesser importance) Locarno in general was an attempt to stabilize capitalism as a whole, i.e., to halt the further decay of the various capitalist countries thru a mutual understanding according to which the contracting powers agreed to limit their respective greeds, so as to let their neighbors get a respite in these harrowing times. The “spirit of Locarno” consisted in the working out of something like a general modus vivendi instead of sharpening the conflicts and inflating “national interests,” the demands of the national bourgeois groups. Not much importance can be attached to the “disarmament conference” that was to spring like a peace-flower out of the soil of Locarno. However, capitalist Europe, where the number of soldiers is at present exceeding that of 1913 by one million, the total disarmament of Germany and Austria notwithstanding could well afford a partial and proportional disarmament without the least injury to the interests of capitalism and militarism. On the contrary, such disarmament would make it possible to divert large sums into other capitalist channels at the same time rendering the war machinery even more efficient thru the scrapping of obsolete armaments and the introduction of most modern methods.

The pacifist aspects and tone of Locarno were necessary for European capitalists mainly to pacify the working masses in the various countries. Locarno was to spread the illusion of a hew pacifist-democratic era. Locarno was to show the masses everywhere, that the Communists are in the wrong when they assert that capitalism has entered the era of decay and ruin. Locarno was to serve as a shining example of the possibility for the present parliamentary system, based on private property, to make the world safe for peaceful endeavor.

5. Locarno and the Soviet Union.

If Locarno was thus meant to manifest the constructive powers of the capitalist world, it was at the same time planned as a united front against the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics. England is interested in choking the Soviet Union not only because the latter is a source of inspiration and admiration for the oppressed nationalities of India and for the other colonial slaves and because the English workingmen have begun to conceive of a Soviet revolution as a way out of their sufferings; France is interested in throttling Soviet Russia not only on account of the milliards of czarist debts and on account of the Moscow influence both among the workers, the peasants and the colonial slaves; Italy is ready to sink its fangs into Russia not only because of all the above causes and to the fact that Leninism is the only real enemy of Fascism, but all these countries have, besides, a special economic interest in the overthrow of the Soviets, namely a market for the European manufactured products. England as well as France and America look with disfavor upon the growth of Russian industry. All of them, including Germany, would rather see Russia an agrarian colony of European and American capitalism. In a world where the difficulties of selling industrial products are continually mounting, the western powers would rather see in Russia a peasant people obtaining industrial products from abroad at a substantial price and providing the western world with cheap bread-stuffs and raw materials. A backward agrarian Russia would make it possible for Germany to sell the products of her factories and promptly deliver Dawes’ Plan payments and this would free part of Europe and other countries from German competition, thus leaving greater elbow-room for England. This golden dream, however, is an impossibility as long as the Russian state is piloted by the Soviet government which is painstakingly building up the industrial apparatus and carefully controlling its foreign trade thru the government monopoly. Locarno was planned as a united front of capital against the Soviet Republics with the view of dominating Russia economically.

6. Locarno and the United States.

Behind the Locarno wedding party stood the capitalism of the United States. Outwardly America was careful to make the impression of non-interference in European affairs. True, the Dawes’ Plan is American-made, the treaty of Versailles bears American signatures, and none of the international conferences of the last seven years failed to see American representatives in the role of “unofficial observers.” Formally, however, America stood aloof. American capitalism chose the most favorable situation, all rights and no duties.

In reality, the enormous amounts of American capital invested in European countries, the dependence of American bankers on the situation in Europe make it impossible for the American government to remain neutral. American capitalism cannot permit German capitalism to go bankrupt. American capitalism needs a France that is capable of paying her debts. America is the greatest competitor of England in the world market and the future enemy of England on the battlefields. But, for the present, America cannot allow England to be convulsed by a revolutionary labor movement. America is peacefully trading with the Soviet Union, but as long as there is Communism in Russia, the greatest capitalist power in the world does not feel-secure.

America need not pay attention to the details of European politics; she need not spend tedious hours around the conference table. One hint from Wall Street or from the White House, and Europe calls conferences, works out agreements, talks stabilization, declaims the beauties of a democratic-pacifist future. Coolidge’s speech of last summer wherein he declared that Europe was in a bad plight due to eternal bickerings and conflicts and that America was about to wash her hands of that sinful and hopeless continent, is still in everybody’s memory. Capitalist Europe cannot allow America to “wash her hands,” i.e., to collect her bills. Capitalist Europe responded to that memorable speech by the conference of Locarno. Locarno was, for America, a political Dawes’ Plan—stabilization of Europe was to make Europe safe for American investments. At the same time Locarno was to be the fulfillment of a wish uttered by Secretary Hoover not so long ago—a “Dawes’ Plan for Russia.” In return, America promised to enter the League of Nations thru the back door of the World Court and thus to become not only an actual but also a formal political partner of European capitalism.

7. Locarno and the League of Nations.

All this pacifist romance was to concentrate around the League of Nations. Germany was to enter the League and thus become a “collaborator” of the other powers. The pact of Locarno was to be part of the League legislation. The League’s power over Germany and the fact that Germany brought into the League not a mailed fist, but the “ideas of justice and right” was to prove the “peace power” of the League and to lend it new prestige. The fact that the League had gathered under its wing all the nations of the world, save the U.S.S.R., was to prove its greatness. The Socialists of all countries, the International Socialist Congress (the Second International), the leading Socialists everywhere (Hillquit in U.S.) experienced a new love for the League of Nations. Capitalism and socialism united in praise of this child of Versailles. International Socialism did its utmost to prove that Locarno was not aimed against the U.S.S.R., that Locarno was the beginning of a new free co-operation between nations.

After Locarno—Geneva!

ALL this glory is now a heap of ashes. Locarno is dead. “The spirit of Locarno” revealed itself not as a dove of peace with an olive branch in its mouth, but as an old witch with teeth of copper and claws of steel. The League of Nations received a blow from which it will not recuperate. The gloom in the camp of capitalism is that following a profound catastrophe.

After Locarno came Geneva to prove that the competitive struggle between the various national capitalist cliques is stronger than their consciousness of the necessity of at least a partial and temporary understanding for concerted action, that the contradictions within capitalism are stronger than its desire to form a united front against the common enemy.

It does not matter that at the last moment a victim was found to bear the brunt of formal guilt of the failure of Geneva. Nobody believes that Brazil of her own accord and on her own initiative declined to vote for the admission of Germany into the League Council. Even the arch propagandists of the bourgeoisie are forced to admit that if it were not for ten days of scandalous bickerings and haggling behind closed doors, Senor Mello Franco would never have had the courage to come forth with his veto. Senor Franco and his government are here in the role of the notorious switchmen to whom, in czarist Russia, all train wrecks were attributed. Behind Brazil and her representative stood the wolves of world diplomacy utilizing the veto as a shield for their shameful defeat.

And it makes no difference that at the eleventh hour Briand made it his business to laud the “spirit of friendliness and compromise” alleged to have been manifested by the Germans at Geneva and that Chamberlain was “happy to announce” that all difficulties among the seven Locarno governments had been removed. It does not matter that the Locarno signatories issued a solemn declaration asserting that the work of peace as accomplished at Locarno remained intact. All this eloquence only proves that at the last moment the capitalist diplomats had become frightened by their own defeat and attempted to cover with phrases the abyss that had opened under their feet. The abyss is there. It is dark and menacing. In it are buried all the hopes, prospects and illusions that were connected with Locarno.

The Differences at Geneva.

We do not know what actual differences brought about the collapse of Geneva. It is understood that France insisted on a permanent seat for Poland in the League Council to which Germany did not agree. It is understood, on the other hand, that Sweden and Czecho-Slovakia were willing to give up their non-permanent seats in order to make the entrance of Poland possible, and that the “high contracting powers” had given their consent to this compromise. The fact, however, remains that Germany has not entered the League and that all the beauteous Locarno illusions burst bubble fashion, because the capitalist powers could not agree on how to divide the world. The separate interests of the individual capitalist robbers proved stronger than the fear of chaos. This is one of the curses of capitalism. This is the power that leads to imperialism and to wars. It has undermined the capitalist order the world over. The centrifugal forces that brought about the eruption of 1914-1918 are at present in operation with greater tension. Chaos under such conditions is inevitable; proletarian revolution the only salvation.

Balm of consolation is being poured on the wounds of Locarno. The solution, it is declared, has only been postponed until September. Everything is alleged to be in the same situation as before the “hitch” of Geneva. But behind these consoling phrases there is a deep melancholy and not much far-sightedness is needed to comprehend that if no agreement could be reached in March when everything was so bright and rosy, it may be just as impossible to reach an agreement in September after six more months of continuous quarrels. The League of Nations hastily sent out invitations to a conference on disarmament and a decision was made to study the League Constitution with a view to changing it in the future. The prospect of a conference to study the American reservations to the entry into the World Court is also held forth. But all this cannot dispel the gloom. The revision of the League Constitution would have to be accomplished by the same wolves who flew at each other’s throats at Geneva. Disarmament under the auspices of a discredited League would be only a mockery. The anti-League voices became particularly virulent in America after the Geneva debacle.

The League After Geneva.

The League emerges from Geneva a weakened, discredited institution, a ghost of itself. It is quite possible that quack physicians will try to mend its torn limbs and cover the rifts with adhesive plaster. The forces of destruction remain. The explosives which in Geneva revealed themselves in such spectacular manner, will continue their work on a growing scale.

The Results of Geneva.

The greatest socio-political result of the Geneva defeat is the death of the capitalist illusion which was to lull the minds of the masses. The League stands revealed before the masses of workers and peasants in such clear outlines that no amount of propaganda will be able to cover its hideous nakedness. What will Baldwin’s government bring to the embittered masses of English workers? What can France offer to her dissatisfied millions? How can Germany face her starved and exhausted slaves? Neither the purring words of the bourgeoisie, nor the sourish honey of social-democratic speeches will be able to quiet the masses. The socialists themselves are witnessing a growing differentiation between their right and left wing, a process that began some time ago and that will only tend to increase the dissatisfaction of the growing class conscious sections of the proletariat. As far as influence over the masses is concerned, Geneva is the most glaring, the most flagrant defeat. If there was anywhere among workers and peasants a lingering belief in the constructive forces of the present system, Geneva has extinguished it for ever. The field is free for the communist parties who will know how to utilize the situation not only in Europe but also on this side of the Atlantic.

The Defeat at Geneva Is a Victory for the Soviet Union.

The defeat of Geneva is a double victory for the Soviet Union, first, because a hostile united front has failed to materialize; second, because the correctness of the Soviet solution of the national problem has been proven once more, Two systems of combination of nations made their appearance on the world arena after the war: Sovietism—a federation of autonomous national states which, having abolished private property in the means of production and having instituted the proletarian dictatorship, laid the foundations for a real economic and political co-operation to the welfare of all; and second, the League of Nations which, based on private property and capitalist exploitation and oppression, attempts to combine the individual states for common action. The former has grown, stimulated industry, improved agriculture, developed culture, witnessed an unparalleled growth of the cultures of the various nationalities, created real friendship and brotherly understanding between the individual states and nationalities composing the Soviet Union. The latter has gone from crisis to crisis, it has proved powerless to overcome the appetites of the individual states, to bring about a tolerable compromise, to stop the decay of the economic fabric and the degeneration of political power. In Geneva the entire League ideology received a mortal blow.

The defeat of Geneva is the victory of Moscow!

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1926/v5n07-may-1926-1B-WM.pdf