The second half of Piatnitsky’s valuable report on two years of reorganization in the Comintern and its sections deals with trade union issues in Germany, Britain, Czech-Slovakia, France, and the U.S. with others. Again, this report, full of facts and figures on the state of Communist Parties in the mid-1920s, will be of interest to all students of Communist history.

‘Achievements and Tasks in Factory and Trade Union Work’ by Osip Piatnitsky from Communist International. Vol. 4 No. 9. June 15, 1927.

(This article is a continuation of the article on “Achievements and Immediate Tasks in Organisation” printed in our issue of May 30th.)

WE find in the industrial centres of all countries that many factory groups are carrying on splendid work and taking the lead in their factories.

Here are some instances of such groups.

Austria.—There are 1,700 workers in the Warholov factory, 537 of whom belong to the Communist group. At the elections of the Factory Committee in 1927, the Communists received 1,044 votes and the Social-Democrats 575—together 97 per cent. of all workers belong to the trade unions. The factory trade union committees are composed of 65 Communists and nine Social-Democrats.

Great Britain.—The machine-minders of the reactionary “Daily Mail” refused to print an article directed against the miners prior to the General Strike. This was done under the influence of the Communist group. The group publishes its own shop paper in that institution.

During the General Strike only a few workers of Smith’s metal workshops carried out the decisions of the General Council concerning the strike. The group issued a special number of the factory paper in which it called upon the workers to join the strike. In addition to that it organised a meeting outside the factory during the dinner hour, as a result of which all workers left the factory.

America.—It would seem likely to be very difficult to organise a Party nucleus in the Bethlehem steel factory. However, there is a nucleus there which is continually gaining in strength. At the time of the election of the company union managing board, the Communist nucleus put up its own ticket and received 700 votes. The opposing ticket received half that number. As a result of the election, the company union came into the hands of the Communists.

There is an automobile factory employing 3,000 workers. In that factory the members of the Party group circulate their leaflets and factory paper through the conveyor, which carries the various automobile parts in the process of production.

Against the Trusts

The Steel Trust employees in Michigan are carrying on a campaign against the trust, under the leadership of the Communist nucleus, for the introduction of safety measures against mine catastrophes, such as happened some time ago when 4o workers were left for hours down in the mines. This campaign has great success among the workers.

Germany.—The preparatory work in recruiting new trade union members decided on by the A.D.G.B. (German Federation of Trade Unions), and the elections to the “Workers’ Congress” were carried out by almost all Communist factory groups in Berlin, particularly the groups in the large factories. The campaign increased the trade union membership and together with it, the influence of the Party group in the factories and fractions in the trade unions.

France.—There are 1,500 workers in the “X” Metallurgical factory, 1,200 of whom belong to the Red trade unions (an unprecedented percentage in France). A thousand copies of the factory paper are printed. There are 120 members in the group (the recent recruiting campaign brought in 16 new members).

In the “Y” factory there are 2,000 workers of whom only 25 belonged to the Red trade unions before the organisation of the factory group; now about 100 belong to the Red trade unions. At the beginning, the group consisted of only a few members, and now it has 30.

Czecho-Slovakia.—The L. No. 1 factory group (in the Brinn district) had 6 members in 1924: by September, 1926, it already had 32 members. The group organised 48 general meetings of the factory workers and is now issuing its own factory paper.

Prior to the reorganisation of the Sections of the International on the basis of factory groups, the passivity of the Party membership reminded one of the passivity of the members of the Social-Democratic parties. All questions were decided by meetings of Party officials. Local Party conferences or general membership meetings were held rarely. Live local organisation work commenced usually only before same great events, as for instance, before a Party congress or before the elections to some representative organs of the Party. Now the situation has changed considerably. The groups consider and discuss all most important problems facing the Party.

Factory Newspapers

Prior to the reorganisation there were no factory newspapers anywhere. I have not heard of any cases in which the Party organisations issued circulars addressed to the workers in individual factories, even on important events, prior to the reorganisation. At present the factory newspapers are an inseparable part of the work of the groups and play an enormous role in the life of the Party local organisations. This is fully verified by the figures given below (which are by far incomplete) concerning papers issued by the larger sections of the Communist International.

America.—There are 40 factory newspapers issued regularly in America. Of these 38 have a circulation of 1,000 to 2,000.

There is one factory paper in Detroit with a circulation of 10,000 copies; and the “Ford Worker,” issued by the group of the Ford automobile factory, has reached a circulation of 20,000 to 22,000 copies. These papers are sold.

Great Britain (incomplete figures).—There are 24 factory papers regularly issued in London with a circulation of about 8,000 copies; 12 of these papers with a circulation of about 3,300 copies are issued by the railway shop groups.

There are three factory papers in Liverpool with a circulation of 3,300 copies. In South Wales 16 pit papers are issued in the mines.

Germany.—There are 170 factory newspapers issued regularly throughout the country. Of these 101 are issued by the Berlin-Brandenburg organisation, 10 by the Erzgebirge-Vogtland district, 10 in the Hessen-Frankfurt district, and from one to eight papers in each of the remaining districts.

France.—There are 300 factory papers with a circulation of from 100 to 1,000 copies throughout the country. Comrade Crozet published in “Cahiers du Bolchevisme,” of 28-2-27 the following figures concerning the number of different factory papers issued in the Paris District.

January—19, February—30, March—52, April—49, May—34, June—35, July—66, August—46, September—88, October—70.

Czecho-Slovakia (incomplete figures).—There are 120 factory papers published in eight out of the 24 districts of Czecho-Slovakia. Towards the end of 1926 we received statistics concerning the Communist Party of Czecho-Slovakia indicating that there are 116 factory newspapers. All combined have issued 806 numbers with a circulation of 82,312 copies. This makes an average of seven issues per factory, with a circulation of 103.

In most cases, the factory papers are printed and contain fairly good caricatures. In many countries they are issued illegally, but here and there they are legal and even print advertisements which gives them an income enabling them to continue publication. It may be pointed out that working men and women, including the members of the Social-Democratic parties. National Socialists and Catholics are eager to get hold of the factory papers.

These papers are already a mighty instrument in the struggle for influence on the working class. But this influence could be considerably multiplied if the papers were properly utilised, which unfortunately is not everywhere the case.

Shortcomings

We shall now deal with the shortcomings in the work of the groups and the measures necessary to overcome them.

(a) The factory groups are on an average very small. In a great number of factories there are only one or two Communists. Most of the groups exist in the small and medium enterprises. The percentage of large factories with factory groups is very small, and the groups compared with the number of workers employed are also small. It is characteristic that this is to be noted everywhere, as has already been pointed out above.

America.—In Chicago out of the 24 groups, only 12, with 96 members, are in large factories; the other 12 are in small and medium enterprises.

Out of 300 factory groups in New York, only 12 are in the metallurgical industry and four in the wood-working industry. All others are in small shops and factories. Out of 300 factory groups, 159 (53 per cent.) are in the tailoring industry. Only 12 groups have more than 10 members each. The rest have three to four-members. Many factories employ only one or two Communists.

The Ford factory, employing 60,000 workers, had 120 group members (the number has now been reduced).

Great Britain.—Most of the groups of Great Britain are in the mines. Only a few are in large enterprises. There are groups in very few large factories. The Communist Party does not work with sufficient energy in the textile industry, and the number of groups in that industry is very small. The membership in the groups is also very low.

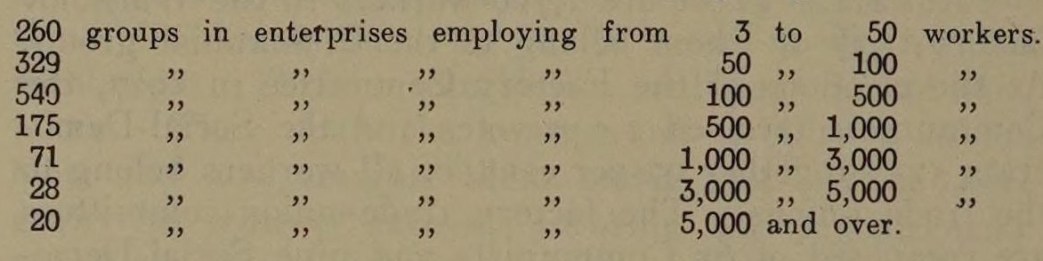

Germany.—Of the 1,426 factory groups there are:

Many Groups too Small

If we consider the enterprises employing 500 workers and over as large enterprises we get the following:

21% of the groups are in large enterprises, 39% in medium, 40% in small.

We may take it as a general phenomenon in all countries that the greatest numbers of groups consist of one or two Communists working in a factory. They cannot, of course, organise a group or carry on normal Party work in the factories.

France.—In the organisation report of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of France of 15-10-26 we read the following:

“…It still remains a fact that the. Party recruits skilled workers from the small enterprises. We must go into fully the question of winning over the large factories.”

Czecho-Slovakia.—There are groups only in 13 factories, employing 3,200 workers out of the 44 chemical factories in Czecho-Slovakia.

Of the 35 textile factories employing 12,000 workers there are Party groups only in two employing 2,000 workers.

Of the 22 groups in the Ostrau district, 11 are in enterprises employing 31,800 workers.

Victimisation

This general phenomenon is due to the terror used by the employers. Regardless of the fact that the Communist Parties are legal in the countries concerned, the groups are, nevertheless, compelled to work underground. Just as soon as the employers learn, through their spies in the factories, that any of the workers belong to the Communist Party, they discharge them; they know that the reformist trade unions will not defend victimised Communists. Thrown out of work, the Communists find it difficult to secure a job owing to the unemployment prevailing in all countries.

Thus members of the Communist Party of Great Britain have been discharged from the big Armstrong and Vickers concerns.

In Germany most of the factory group members were discharged from the Seidel and Neumann dye factory and many other factories.

In the Ostrau district in Czecho-Slovakia the sacking of Communists is a very frequent occurrence.

In France the majority of group members have been discharged from the Michelin, Citroén and Peugeot factories, and the Renault, Paris, automobile factory discharged the entire group, whose membership list fell into the hands of the administration after a strike of 10,000 workers.

In many factories in Germany the Fascists have organised their own groups to counterbalance the work of the Communists. These groups naturally intensify the espionage in the factories. In some countries, like France, Germany and the United States, an extensive espionage system is developing in the factories at the expense of the employers: The result of these terrorist methods is that many Communists do not join the group in their factories, which undoubtedly affects the numerical strength of the groups, and, if they do join them, they remain passive and try to restrain the nucleus from doing any active work. The group members thrown out of factories try to find jobs in small enterprises where the regime is less severe.

Groups that do Nothing

The situation is still worse in connection with the activity of most of the existing factory groups. Many of them, although they are in factories, shops and other enterprises, can be only formally considered as “factory” groups. Their activities are not carried on in their own factories, and they do not deal with the problems confronting their own enterprises. The only actual difference between the former territorial organisations and the above-mentioned groups consists in the fact that now workers of one factory or enterprise meet together whereas formerly Party members living in one neighbourhood met together. They discuss questions concerning Party affairs, they elect delegates to Party conferences, they receive reports of their delegates, and they carry on their work just as it was carried on in the old form of organisation.

There are also factory groups Sachin only in technical work, such as the distribution of literature, factory newspapers, posting proclamations and placards. Both types of group exist in all countries.

How can we explain this? In the first place, by the fact that the Party members are still under the influence of the organisational traditions and customs of the Social Democrats, whose organisational forms were adapted to election campaigns, for which purpose they were based in the territorial principle. Besides, in those organisations the legal parties could work unmolested and the terror of the employers could not affect them.

Neglecting the Factory Groups

Secondly, this may be explained by the fact that almost all big mass campaigns were and are still being carried out by the Communist Parties outside of the factory groups, and the every-day work of the groups is not directed by the leading Party organisations so as to keep it in contact with the political tasks of the Party. Such a policy in the Communist Parties paralyses the factory groups, and renders them incapable of discussing questions connected with the campaigns, or participating in working out plans and putting them into effect. For the same reason the groups have no material on the basis of which they could carry on their agitation among the factory workers. The result is that the members of the groups are torn away from the workers in their factories.

To prove my point, I shall cite some oral and written reports of representatives and organs of the Central Committees of the larger legal Communist Comrade Birch (America) says in his report of 27-12-26 to the Organising Department of the E.C.C.I. the following:

“The campaign in defence of foreign workers was carried on outside of the factory groups. Although some groups were interested in this question and distributed our circulars, their interest did not express itself in a broad mass campaign. (*There are many foreign workers in America; the campaign referred to was a campaign against a Bill which proposed to deprive the foreign workers of some of their rights; it could therefore have been very successful in the factories.)

“The campaign in favour of the “Daily Worker” was not sufficiently energetic in the factories. Of the 11 factory groups of one New York ward about which we have information, 9 groups did not secure a single subscription, one group got one subscription and one group 47 subscriptions.”

Comrade Birch concluded this part of his report by saying:

“We cannot draw the factory groups into the Party campaigns. Our Party will have to solve this difficult problem.”

In the General Strike

Comrade Brown in his report on the Organisational Conference of the Communist Party of Great Britain in October, 1926, speaking on the work of the factory groups during the General Strike and of their role in the Party campaign connected with the General Strike, said:

“It must be admitted that our factory groups were weak and did not function properly during the General Strike. In some districts the groups stopped functioning altogether.”

Further:

“I do not know to what extent the opinion prevails that our factory groups are of no use to the Party during industrial crises and unrest, but such views concerning our factory groups exist. This is due to the fact that some comrades think that our work must be carried on, in time of crisis, in the trade union organisations.”

In the report of a comrade from the 2oth District Organisation in Berlin we read:

“Why do we see such passivity? We must make the factory groups political. We must tell the comrades that they should be able to reply to the questions and arguments of the supporters of the Social Democrat…Ever since I have been a member of our factory group it has never discussed any of the questions concerning the enterprise. All we hear is reports from delegate Party meetings and about Party quarrels.”

In the Renault automobile factory (France) there was a strike of 10,000 workers in May, 1926, which came as an absolute surprise to the Communist group in that factory (from the report of the E.C.C.I. representative). The group which was thus separated from the life of the factory was unable to react to the most immediate and vital problems of the workers in their enterprise. This, together with the terror, has developed among Party members the desire to carry on their Party work in the territorial organisations.

Street Groups

(c) Street Groups.—The street groups have acquired greater importance in many countries than was ascribed to them in the instructions and the resolutions of the International Organisation Conference and the organs of the C.I.

Street groups never played any role in the organisational structure of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. It is impossible to do without them abroad. Facts have proved this. Originally the street groups were created with the purpose of organising those Party members who were not working in the factories, such as domestic workers, artisans, janitors, porters, intellectuals, etc. The field of activity of the street groups was supposed to be agitation among the proletarian population in their vicinity, distribution of literature in the neighbourhood. They have the same Party rights as the factory groups. In reality, however, the street groups have become transformed into full-fledged Party organisations, while the factory groups eke out a miserable existence.

This is partly due to objective causes, but primarily to the wrong attitude of the higher Party organisations. As an objective condition, we can take the fact that unemployed Communists try to get into the street groups. These comrades cannot be compelled to go out of their way to attend factory group meetings or to carry on Party work among the factory workers if most of them live a distance away.

Such demands can be put only to the more active Party members, upon whom the further activity of the factory groups in which they used to work previously largely depends.

Why Factory Groups Fail

It is wrong if workers and clerks working in factories where there are factory groups or where such could be organised do not want to participate in the Party work in these factories, but prefer to join the street groups. Such cases are entirely due to the local and district committees. These committees do not combat this phenomenon, but, on the contrary, they carry on most of their campaigns through the street groups, leaving the factory groups in many cases without any leadership.

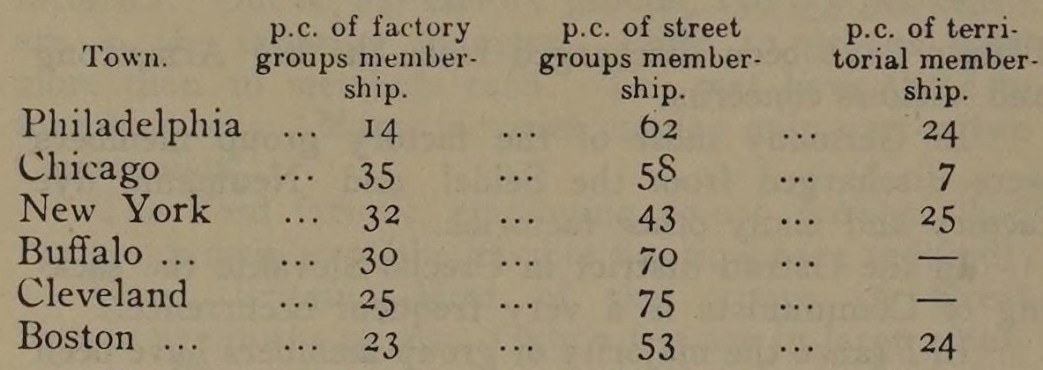

There are in America 440 factory groups and 400 street groups. On an average the factory groups have 26.5 per cent. of the membership, the street groups 60.2 per cent. and the old Party organisations 13.3 per cent.

The figures in the various towns are as follows:

The average percentage of the factory group membership in some German districts is somewhat higher than the percentage in America. The factory groups of Berlin and Ludwigshafen contain the majority of Party members, which is a sign that the groups in those towns are working properly and receive support and real leadership from the higher Party organs, as a result of which the members are not anxious to join the street groups.

Comrades may think that since the street groups are so strong numerically they must also be active. However, in most cases their passivity reminds us of the passivity of the old territorial organisations. The street groups revive only before elections to some representative bodies. In this respect they have much experience, as the old organisations were prior to their reorganisation engaged only in this kind of work.

It was pointed out above that most of the campaigns were carried out in the residential districts, but it need not be concluded that the work was carried out by the street groups. The campaigns were carried out by the members of the factory groups after their working hours and on holidays when they were home. (There were | cases in Berlin when members of factory groups were appointed to canvass from house to house in their neighbourhood during the various campaigns.)

Local Officials

(d) The Question of Local Officials.—The question of local officials is very important. In the old organisational forms it was sufficient if there were two or three officials in an organisation to handle the work. On an average there used to be two or three officials to every 100 to 150 Party members. With the reorganisation on the group basis a minimum of one official (group leader) is necessary for every group.

To this must be added the fact that the reorganisation made necessary the creation of many locals in the large towns (there are over 100 in Berlin) which necessitates more officials in the local and district committees to carry on the work. We hear from all legal organisations that there is a shortage of Party officials, which greatly interferes with getting the factory groups to be active.

Many comrades give suggestions of how to create new ranks of officials. Some propose to raise the level of Marxian education, others propose the organisation of Party schools. Of course, this is necessary, there can be no doubt about that. But new officials can be obtained primarily through the activisation of the existing factory groups. Only by means of active practical work in the groups can we create experienced and tenacious Communists; only from them can we add to their ranks and strengthen the entire Party apparatus.

(e) Help by the Party Committees to the Groups.—

As has already been pointed out, the successful work of the Party depends on the proper functioning and good work of the factory and street groups. No matter how difficult the conditions of Communist work in the factories may be, work can be carried on. The splendid results of the activities of some of the factory groups in every country prove this. We cannot explain the bad work of the street and factory groups through the lack of Party officials. It is quite possible to improve the work of the groups even with those forces which the Parties have, provided they are properly and rationally utilised. This is possible if the work of the lower groups and organisations is given proper leadership. The main reason for the poor work of the groups is the lack of attention they get from the higher Party organs. When some internal Party discussion is in: progress, particularly before elections, the groups are given speakers and plenty of material. But in the everyday work of the groups they receive neither.

Left to Their Fate

At the Organisation Conference of the Communist Party of Great Britain in October, 1926, Comrade Brown, reporting for the C.C. of the C.P.G.B., said that the factory groups were organised and then left to their own fate. No one ever gave them a thought.

He said that the Organisation Department of the C.P.G.B. in investigating the causes for the decline of membership of some of the organisations came to the conclusion in one of its letters that the insufficient support and control on the part of the respective Party committees was largely to blame. The district committees send instructions of a general character to the local Party committees and groups. There are very few cases in which the local district Party committees give any concrete instructions to the factory groups applicable to the conditions prevailing in the respective factories.

What has been said above is confirmed in almost exactly the same words by the Berlin-Brandenburg district committee in its report of December, 1926. A comrade from the 9th Berlin District, speaking about the recruiting campaign, same to the conclusion that there is not enough material, and that it is necessary to publish a popular pamphlet on the question of rationalisation.

Comrade Crozet speaks in No. 62 of “Cahiers du Bolchevisme” (organ of the C.P. of France) of the same situation. He also arrives at the same conclusions, namely, that so long as the higher Party committees do not come to the support of the groups in their work everything will remain as before.

It is essential for the legal Communist Parties to inaugurate an energetic campaign towards the elimination of the defects in the work of the groups, and for the improvement of the leadership and control. They must supply the groups with speakers and printed material, needed by the workers’ groups, concerning elections, recruiting and other political campaigns. Only then will it be possible to liven up, to raise the activity and the political life of the groups.

Only under these conditions will the groups be able to promote the necessary Party cadres, without which the Communist Parties will be unable to become mass proletarian Parties.

Work in the Trade Unions

It has already been remarked in the previous article that although the Communist Parties exercise a strong ideological influence on the working class, within the trade unions they are very weak.

During the struggle of the British miners the C.P. of Germany did not succeed in enforcing resolutions on material aid for the British miners, in preventing the introduction of overtime work in the mimes or in prohibiting the export of coal to England in any of the national unions. Even more: the C.P. of Germany has so far been unable to stop the treachery of the German Federation of Trade Unions towards the entire German working class (practical dropping of the eight-hour day, rationalisation at the cost of the workers, which has led to an army of 1,500,000 unemployed), and the treachery of central committees of the individual unions in the conclusion of agreements with the employers.

The explanation of that lies in the fact that the C.P.G. has no majority in any union.

The C.P.G.B. is in no better position: during the General Strike and the miners’ struggle the C.P.G.B. and the Minority movement played a conspicuous role in the Trades Councils, strike committees and councils of action, but they succeeded neither in defeating the disgraceful compromise which the railway unions concluded with the companies after the General Strike, nor in the agitation for material support for the miners in the most critical moment of their struggle in any one of the big unions. The same applies in outline to the carrying out of the embargo. In spite of the popularity of this slogan among the British working class, the C.P.G.B. and the Minority movement did not succeed anywhere in preventing the transport and unloading of coal. The reasons for this are the same as in Germany.

At the special conference of the Minority Movement early in 1927 trade union organisations with a membership of 1,080,000 were represented. In spite of the very great number of unions in the trade union movement, no union of any importance is affiliated as a whole to the Minority Movement.

As for Czecho-Slovakia and France, where there are independent red trade unions, over which the respective Communist Parties exercise an indisputable influence, the conditions there are in general only a little better than in Germany and England.

Is It Good Enough?

Can the Communist Parties in these capitalist countries be contented with such a state of affairs, that although they can lead great masses in demonstrations and receive millions of votes at elections, they are at the same time unable to prevent the reformist trade union leaders from betraying the interests of the workers day by day?

How can this be altered? In the first place, by the Communists in the unions doing their work energetically and in a determined fashion in all directions, by concentrating in Communist fractions, which should be rightly directed by the Party. It cannot be maintained that up to the present the sections of the C.I. have fulfilled these conditions.

Before all it must be laid down that not all Communists are organised in trade unions. We are not concerned here with merely formal obedience to the decision on the entry of Communists into trade unions. Actual circumstances make it clear that we cannot strengthen our influence in the trade unions of all Communists do not work in the trade unions. The Communist Party by its programme, its slogans, its real fight against the bourgeoisie, attracts the workers to itself. In the most difficult elections workers who are not at all Communists give their votes to the C.P. The Communist workers find themselves in surroundings on which they can and must exercise influence. It may be assumed that every Communist, on the average, has around him ten workers whom he can influence. Therefore every Communist who remains out of touch with his Union is refusing to exercise influence on those around him; therefore he does not promote any increase in the Communist influence in the trade unions: on the contrary, he helps towards a decrease in this influence.

Even more, such Communists check the growth of class trade unions. How, in actual fact, can Communist Parties in capitalist countries perform successful recruiting work for class trade unions among the workers and employees if all Communists are not organised in trade unions?

Members Not in Unions

Statistical statements of the Org. Bureau of the E.C.C.I. on this question from all countries show that many Party members are not organised in trade unions, and by reason of that the influence of the Communist Parties in the trade unions is weakened. We give below figures from a few of the legal Communist Parties relating to the question.

Czecho-Slovakia.—According to statistics given in March, 1927, figures relating to 92,691 members of the Communist Party of Czecho-Slovakia (out of a total of 138,000) show a trade union membership of 49.2 per cent. The peasants, handicraftsmen, small shopkeepers, professional workers, housewives, etc., who are members of the Party, and are not eligible for trade union membership, total 22,936 or 24.7 per cent. We can therefore say that 26 per cent. of the Party members capable of being in trade unions remain outside of them.

America.—The statistics of the Org. Bureau of the American Party show that only 40 per cent. of the membership of the Workers’ (Communist) Party are organised in trade unions.

Britain.—At the Organisation Conference of the C.P.G.B. it was reported that go per cent. of the Party membership were in trade unions. The C.P.G.B. is in this respect an exception. On the average not more than so to 55 per cent. of the members of the Communist Parties are organised in trade unions.

The Communist Parties of Great Britain, Germany and Italy have, of course, strong positions in the Amsterdam trade unions (in these countries there is no split in the trade union movement). Thanks to the energetic work of the Italian Communists, the Confederazione del Lavoro (Amsterdam), which had been dissolved by the reformist trade union leaders in deference to the Fascists, has again begun to work. Italian Communists have strong influence in the Trades Councils of the industrial towns and in the large unions. Unfortunately the sphere of activity of the Italian class trade unions is very limited, since it is obligatory on all workers to enter the Fascist trade unions (contributions are collected when wages are paid), and only Fascist trade unions are permitted to conclude agreements with the employers.

The C.P.G.B. has great influence in some unions and in the local branches. Not long ago Party locals in a few districts succeeded in getting their members elected as secretaries of trade union organisations (in England elections of salaried trade union officials occur very seldom).

Fractions in Germany

It can be said that the C.P. of Germany, in the elections which took place a short while ago, had in all the big trade unions on the average not less than 25 per cent. of the members behind it. In many instances the number of votes which were given to the Left opposition increased in comparison with the previous elections. The position of the German Communist Party in the trade unions is becoming firmer from day to day. That has already been admitted by the reformist leaders. Their work would be much more successful if the 20 per cent. or so of Communists who are still outside the unions would become active union members, and if the fractions worked in a better fashion than those existing in 1926 did. I think it is necessary to emphasise that the successes attained in the trade unions in the course of the last year are due to the existence of the Communist fractions in the unions, although this work is far short of what could be called good.

There already exist trade union fractions, if not everywhere. What about their activity?

The district committee of the Ruhr area states in its report of October, 1926, that there are 213 trade union fractions in its area, of which 4o per cent. work very badly, 40 per cent. work not particularly well and 20 per cent. work well. (The percentage of fractions not working relatively to those working badly is not only in Germany but in all other countries higher than the percentage of factory groups not working relatively to those working badly.) If 20 per cent. of the Communist fractions are working well it shows that Communist work in the trade unions is possible; it has only to be done effectively.

But why do the Communist fractions in the trade unions function so badly?

Fractions that Don’t Meet

One of the causes is that the fractions do not include all Communist trade union members, and all members of the fraction do not turn up to fraction meetings.

In the Pennsylvania district of the United Mine Workers of America there are 650 Communists, of whom only 75 are in the fraction. In Berlin in January, 1927, of the 14,000 Party trade unionists only 1,026 took part in the fraction meetings. The fraction in the German Metal Workers’ Union, Stuttgart district, includes 209 comrades. Not more than 10 per cent., however, take part in the meetings. At the last general meeting of the union in Frankfurt only four out of 209 Communists were present.

The cause of this defect is that the Party organisations have not taken it upon themselves to make clear to the existing fractions their importance, and to show them how practical work must be done. The Party committees do not control the work of the fractions systematically.

Unfortunately it often happens that our comrades, although they make the right demands, corresponding to the interests of the masses, do nothing among the unorganised workers and the trade unionists to further these demands. In the Ruhr district, for example, the C.P. in their fight against the lengthening of the seven-hour shift put forward the slogan, which was very popular among the miners: “From April 1st, 1927, all work in the pits after seven hours will cease.” The C.P. in the Ruhr district, however, did insufficient work among the miners and the trade unions organisations to forces similar resolutions from the mining union controlled by the reformists to draw them into the struggle for the seven-hour day. Such work was even more essential since the delegate conference of miners in the Ruhr area took place on the 20th March.

How inexperienced the Communists are with regard to work in the trade unions and how little they understand how to counteract the crushing manoeuvres of the Social Democratic officials by quickly grasping the situation and by adopting the correct course, the following example will show:

This example is drawn from the report of a comrade in the Trade Union Bureau of the Central Committee of the German Communist Party on the conference of officials of the miners’ union in the Hindenburg district (Upper Silesia). Among the 360 who participated in the conference 16 or 17 were Communists, but according to the statement of the local Party organisation there should have been not less than 65 Communists present. And the comrades who did attend the conference brought forward, together with resolutions on very important questions which were intelligible to the miners, such as wage demands, wage agreements, overtime, contract work and unemployment, a resolution of no confidence: against the Social-Democratic chairman of the local administration of the union. The Communists had previously fixed their speakers on all these questions. Five comrades were to speak on the principal questions. Instead of pressing the most important questions into the foreground, our comrades allowed themselves to be caught by the manceuvres of the Social-Democratic Committee, who decided to place the greatest emphasis on the resolution of no confidence before dealing with the very important questions concerning the miners.

As though it were not enough, that the Communists allowed this manoeuvre of the Social-Democrats, they put up at this point only one speaker, on whom the Social-Democrats fell with all their might. The Social-Democrats succeeded in evading a treatment of the main question, and avoided any serious criticism on the part of the Communists. The resolution of no confidence could not be convincingly put forward and fell through. After this defeat the Communists refrained from voting against the resolutions brought in by the Social-Democrats on other questions, which was used by the latter to its fullest extent in their agitation against the C.P.

The mistakes which the Communist trade union fractions commit in their work can be traced chiefly to the lack of support and right direction in their work on the part of the Party leadership responsible for the work in trade unions.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-4/v04-n09-jun-15-1927-CI-grn-riaz.pdf