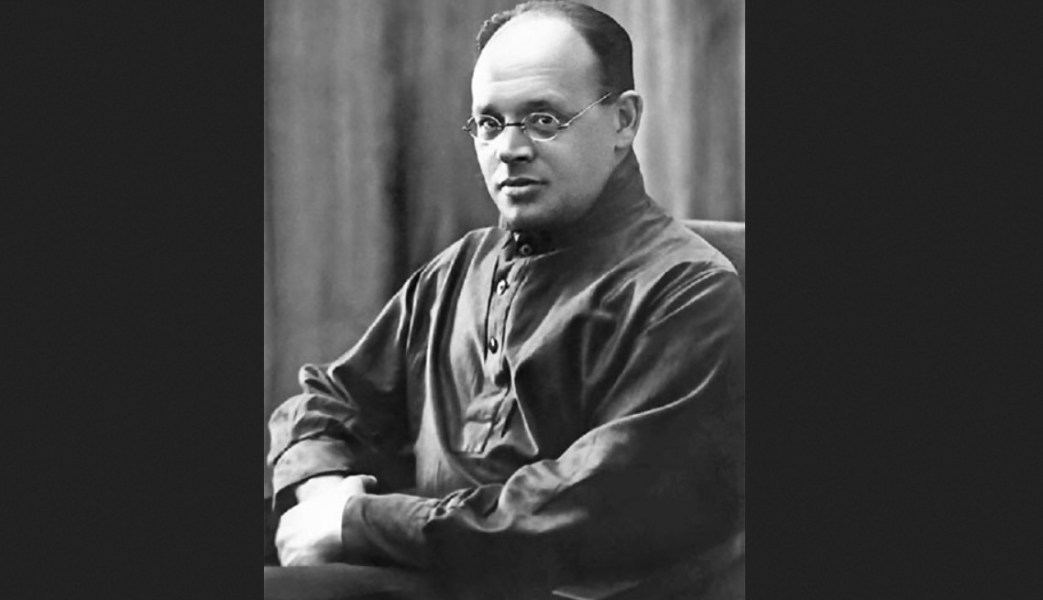

Issac Babel’s unsparing works set in the Russian Civil War, he accompanied the Red Cavalry during the Polish War as a Soviet correspondent, are both a harsh record of the reality of those years, and, often, art of the highest order. Below, a young Jewish soldier crosses the front line between Red and White on the way from Kiev to Petrograd. Babel, among the most celebrated and accomplished authors of the revolutionary generation, was a victim of the Purges. Arrested in 1938 he was executed on January 27, 1940.

‘The Road: A Story of Revolutionary Days’ by Isaac Babel from International Literature. No. 1. 1933.

The front collapsed in 1917. I left it in November. At home mother made me a bundle of linen and rusks. I reached Kiev the day before Muraviev started bombing the town. I was bound for Petersburg. We spent 12 days in the cellar of Heim the Barber’s hotel on the Bessarabka. I got a permit to leave the city from the Commandant of Soviet Kiev.

There is nothing drearier in the whole world than the railway station in Kiev. Temporary wooden structures have disfigured the approach to the town for many years. Lice crackled on the wet boards. Deserters, gypsies and meshochniks1 jostled about pell-mell. Old Galician women pissed as they stood on the platform. A low hanging sky furrowed with clouds was bursting with rain and gloom.

Three days passed before the first train left. At first it stopped every verst but afterwards it speeded up: the wheels clicked more merrily and sang a song of power. This made everybody happy in our cattle-truck. Fast travelling made us happy in 1918. During the night the train shuddered and came to a stop. The doors of the cattle truck parted and the green gleam of snow opened up before us. The car was entered by a station telegrapher, in a fur coat tightened by a belt, and soft Caucasian boots. The telegrapher stretched out his arm and rapped on the open palm with one finger.

“Fork out your papers…”

Near the door a quiet old woman lay huddled up on some bales. She was travelling to Luban, to her son, a railwayman. Next to me Judas Weinberg, a teacher and his wife sat dozing. The teacher had got married a few days before and was bringing his young bride to Petersburg. They whispered to each other about the Dalton Plan until they fell asleep. Even in sleep they were holding hands.

The telegrapher read their document signed by Lunacharsky, took out from under his fur coat a mauser with a dirty, narrow muzzle and shot the teacher in the face. A huge round-shouldered moujik in a fur hat with hanging flaps stood stamping his feet behind the telegrapher. The chief nodded to the moujik, who placed his lantern on the floor, unbuttoned the dead man’s clothes, cut off this genitals with a knife and started stuffing them into his wife’s mouth.

“You turned up your nose at treif2,” said the telegrapher. “Have some kosher.”

The woman’s soft neck bulged out. She said nothing. The train stood motionless in the steppe. Billowy snow sparkled an arctic glare. Jews were flung from the cars onto the road. The moujik led me behind a frosted pile of wood and started searching me. The dimming moon shone on us. A violet wall of forest gave off smoke. Stiff fingers frozen like sticks crept over by body. The telegrapher shouted from the train:

“Jew or Russian?”

“Some Russian!” muttered the moujik, rummaging me. “Could make a rabbi of him.”

He drew his puckered-up, care-worn face near mine, ripped from my drawers the four ten rouble gold coins my mother had sewn in for the journey, removed my boots and overcoat, and after turning me face about, struck me across the neck, saying in Jewish:

“Ankloif, Heim.”3

I set off, thrusting my bare feet in the snow. A target lit up on my back, the bull’s eye passing through my spine. The moujik did not fire.

Amidst columns of pine, in the concealed undergrowth a light danced in a crown of blood-red smoke. I ran towards the lodge. The woodman moaned when I burst in. He was wrapped up in strips of cloth cut from overcoats, and sat in a velvet, cane armchair, rolling tobacco on his knees. The woodman, elongated by smoke, groaned and stood up. He bowed down to my waist.

“Go away, my good man…”

“Go away, my good citizen…”

He led me out to the footpath and gave me a piece of cloth to wind round my feet. I dragged myself into a small town late next morning. As it happened there was no doctor in the hospital to amputate my frozen feet. A feldsher4 was in charge of the ward. Every morning he flew up to the hospital on a small black colt which he tied to a tether, and came in beaming, a bright glitter in his eyes.

“Frederick Engels,” feldsher bent down to the head of my bed, his coals of pupils lighting up, “Frederick Engels teaches the likes of you that nations ought not to exist, but we, on the contrary, say that the nation is obliged to exist.”

Tearing the bandages from my feet, he would straighten himself and gnash his teeth, saying in a low voice:

“Where are they taking you…why is she ever on the move, that nation of yours? Why such disturbance and ructions?”

One night the Soviet took us away on a truck—patients who could harmonize with the feldsher, and old Jewish women in wigs, the mothers of local commissars.

My feet healed up. I set out on a sordid journey through Zhlabin, Orsha and Vitebsk. We traveled in a freight car. Fedyukha, a chance companion, who had followed the great path of a deserter, was raconteur, jester and buffon. We slept beneath the short but mighty, upturned muzzle of a howitzer, and made one another warm in our animal’s lair of a canvas pit lined with hay. Later Lokhna Fedyukha stole my bag and disappeared. The town Soviet had given me the bag which contained two sets of soldier’s underwear, a few rusks and some money.

After two days we drew near to Petersburg—we travelled without eating. I had my last dose of shooting at the Tsarkoe Selo Station. A military patrol greeted the train by firing in the air. Meshochniks were led out onto the platform and their clothes torn from them. At nine o’clock that evening the railway station, a howling den, flung me onto the Zagorodny Prospect. Across the street, on a wall, near a boarded-up pharmacy a thermometer registered 24 degrees below. The wind roared down the tube-like Gorokhovo Street; a gas lamp was swinging over the canal. This cold, basaltic Venice of the north stood motionless. When I turned down Gorokhovo Street, it looked like a frozen field stuck with rocks.

The Cheka was housed in Gorokhovo Street, 2, the former headquarters of the city governor. Two machine guns, two iron dogs, were posted in the vestibule, their muzzles high in the air. I showed the commandant a letter from Vania Kalugin, my non-commissioned officer in the Shuisky regiment. Kalugin had become an examining judge in the Cheka and had written asking me to come.

“Step along to Anichkov,”5 the Commandant told me. ‘“That’s where he is now.”

“I’ll never reach it,” I smiled in answer. Nevsky Prospect flowed into the distance like the Milky Way. The carcasses of horses marked it like milestones. The raised legs of the horses supported a sky fallen low. Their bellies showed white, and glittered. An old man resembling a guardsman went past pulling a toy sled. Exerting himself, he hammered into the ice with leather feet. He had a Tyrolese hat planted on the top of his head, and his beard, tied up in a string, was thrust into his scarf.

“I’ll never reach it,’ I said to the old man. He stopped. His furrowed, leonine face was full of calm. He thought about himself and pulled the sled further.

“That means it’s no longer necessary for me to conquer Petersburg,” I thought to myself and tried to recall the name of the man trampled to death under the hoofs of Arabian horses at the very end of his journey. It was Jiehuda Helevy.

At the corner of Sadovaya Street stood two Chinese in bowlers with hunks of bread under their arms. They marked small portions on the bread with their chilly fingernails and showed them to approaching prostitutes. Women passed them by in a silent parade.

At Anichkov Bridge I seated myself on the pedestal of one of Klodt’s6 horses, My elbow screwed round behind my head; I stretched myself out on the polished slab but the granite struck me and burnt me, tossing and driving me on to the palace.

The door of the reddish wing was open. A blue lamp was shining above the footman asleep in an armchair. His lips were hanging on a wrinkled face, deathlike and inky. A tunic minus belt bathed in light hung over a pair of court trousers embroidered with gold lace. A shaggy ink arrow pointed the way to the commandant. I climbed the staircase and passed several empty, low rooms. Women, painted in dark and gloomy colors, were dancing in rings on the ceilings and walls. Metal lattices stretched across the windows, broken bolts hung on the frames. At a table at the end of the enfilade, sat Kalugin in an aureole of rustic straw-colored hair, illuminated as on the stage. Facing him on the table was a heap of children’s toys, multi-colored rags, and torn picture books.

“So there you are,” said Kalugin, raising his head. “You’re needed here.”

With my hand I moved to one side the toys scattered on the table, lay down on the shining board and…woke up—some seconds or hours later—on a low sofa. Rays of light from the chandelier were playing over me in a glassy waterfall. My rags, cut from me, lay in a pool on the floor.

“Now for a bath,” said Kalugin, who was standing near the sofa. He lifted me off and carried me to an old-fashioned bath with low sides. There was no running water. Kalugin poured water over me out of a pail. My things—a dressing gown with hasps, a shirt and a pair of socks of heavy silk—lay upon straw-colored satin cushions on wicker chairs without backs. The drawers came up to my head; the dressing-gown had been made for a giant—I trampled the sleeves under foot.

“What! Are you making a joke of Alexander Alexandrovich,” said Kalugin, swinging out my sleeves. “The lad weighed about nine poods.”

We managed somehow to tie up Alexander the Third’s dressing gown and returned to the room we had left. It was Marie Fedorovna’s7 library, a scented box where gilded bookcases with crimson streaks pressed close to the walls.

I told Kalugin who had been killed in the Shuisky regiment, who had been elected commissar, and who had left for the Kuban. We then had tea: in the cut glass of the tumblers stars swam in a blur. After drinking them down, we took a few bites of black, mouldy horse sausage. Only the curtains—thick folds of feathery silk—separated us from the world.

A sunset in the ceiling was shining in broken rays: a stifling heat issued from the radiator.

“Let the worst come to the worst,” said Kalugin, after we were through with the horseflesh. He went out somewhere and returned with two boxes—a present from Sultan Abdul Hamid to the Russian sovereign. One was made of zinc, the other was a box of cigars tied with ribbons and paper insignia. “A sa mejeste, Em pereur the toutes les russies—from your well-wishing cousin,” was engraved on the zinc lid.

Marie Federovna’s library was filled with the scent she had been accustomed to a quarter of a century before. Cigarettes twenty centimeters and as thick as a finger were wrapped up in rose-colored paper; I don’t know whether anyone else in the world smoked such cigarettes besides the All-Russian autocrat, but I chose a cigar. Kalugin stared at me and smiled.

“Hang it all,” he said, “maybe they’re not counted. The servants have told me that Alexander the Third was an inveterate smoker. He was fond of tobacco, kvas and champagne. Look at the cheap earthenware ashtrays on the table there. His trousers, I am told, were always full of patches.”

And sure enough, the dressing-gown I had been robed in was covered with grease and had often been mended.

We spent the rest of the night sorting Nicholas the Second’s playthings, his drums and engines, his christening clothes and copybooks with their childish scribble. Snapshots of grand dukes who had died in infancy, locks of their hair, the diaries of Princess Dagmara, letters from her sister the queen of England, all breathing perfume and dust, crumbled away under our fingers. When the princess left for Russia, her girl friends—daughters of burgomasters and State Councillors—bidden her farewell in slanting laborious lines on the fly leaves of the New Testament and Lamartine. Queen Louisa, her mother, ruled over a small kingdom but took care that her children got on well in the world—she married one of her daughters to Edward the VIIth, Emperor of India and King of England; another she married into the Romanoff family; her son George became king of the Greeks. Princess Dagmara became Marie in Russia. The canals of Copenhagen and King Christian’s chocolate sidewhiskers were now far away. This little woman cunning as a fox, flung about in a palisade of handsome officers, giving birth to the last of the rulers, but her birth flowed into the vengeful implacable soil of a strange land.

Not till dawn could we tear ourselves away from this ancient and disastrous chronicle. Abdul Hamid’s cigar was finished. In the morning Kalugin brought me along to the Cheka on Gorokhova Street 2. He had a talk with Yuritsky. I stood behind the hangings which fell to the floor in waves of cloth. Snatches of their conversation floated out to me.

“He’s all right, he’s one of ours. His father is a shopkeeper but the lad broke with him. He knows languages…”

The Commissar for Internal Affairs of the Northern Provincial Commune wobbled out of his office. Behind his pince-nez tumbled out two flabby and swollen eyelids, burnt by insomnia.

I got a job as translator in the Foreign Department. I received a soldier’s uniform and coupons for my meals. In a corner set apart for me in the hall of Peterburg’s former City Governor headquarters I set to work translating the depositions of diplomats, incendiaries and spies.

Before a day had passed I had everything—clothes, food, work and comrades, true in friendship and death, the kind of comrades that can be found in no other country ii the world besides ours.

Thus, thirteen years ago began my glorious life, brimful of thought and of joy.

Translated from the Russian by Padraic Breslin

NOTES

1. Meshochniks—from meshok, a bag—pedlars who sold goods on the sly during the period of Military Communism.

2. Treif—non-kosher.

3. Ankloif Heim—run off, Heim!

4. Feldsher—surgeon’s assistant.

5. A former royal palace in Petersburg.

6. Baron Von Klodt—a well known sculptor.

7. Alexander the Third’s wife.

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1933-n01-IL.pdf