1934 was not San Francisco’s first general strike. 1901 saw the class war in that city rage in all its contradictions as workers came out for themselves and each other as the President visited, flags festooning the waterfront while scum deputized by “law and order” to “keep the peace” wreak havoc. The S.L.P.’s Jane Roulston writes from within its midst.

‘In Darkest San Francisco’ by Jane C. Roulston from The Weekly People. Vol. No. 11 No. 22. August 31, 1901.

Strikes and “Patriotism” in One Wild Revelry.

SAN FRANCISCO, Aug. 10. It is not to be inferred from this title that San Francisco is perceptibly darker than other towns of its size and importance. Let it be remembered that if the sun rises in the East it sets in the West, and its declining rays fall brightly upon our Western Metropolis, gilding the great Trade-Marts of the “Captains of Industry,” as well as their magnificent dwellings, with a radiance more gorgeous, if possible, than the ostentatious splendor which the more tangible gold of the owner has been able to produce, and even having the bad taste to linger at moments upon the squalid homes of the people. But the light of San Francisco in common with the light of the world has not been able to affect the impervious human brain.

CALIFORNIA IN GENERAL.

In her relation to labor movements, and indeed to movements of every kind, California has always taken a stand differing somewhat from that of the other States. This is partly due to peculiarities of climate and production which have brought about peculiar economic conditions, and partly to an idea evolved in the fertile Western brain that the United States is an appendage of California, and that all National organizations depend upon the California locals. It is a difficult task to correct this error, and this may have been one of the many reasons why the Socialist Labor Party found such uphill work in establishing itself here, on its present firm basis. Be that as it may, the State has established her superiority in one particular at least. As a fruit bearing country we may have been equaled; our wine has perhaps been surpassed; our boasted climate may be said to lack the salubrity of Southern Italy; but as a fakir-raising community we stand unequalled, and we challenge the world to prove that we have not out-Kangaroned every other State in this glorious Union.

SAN FRANCISCO IN PARTICULAR.

As was to be expected, the present Trades Union flurry, with its accompanying train of strikes, lockouts, and boycotts, struck San Francisco with extraordinary violence. It was received with enthusiasm by the ever-ready fakir, and kindly welcomed by the “broad-minded” Social Democracy. It manifested itself first in unusual activity on the part of the “pure and simple” Unions and their representatives bodies, the Labor Council,, and the Building Trades Council. An interesting controversy arose between these august bodies, in which it appeared that Pierce of the Labor Council was an “emissary of Gompers,” and that McCarthy of the Building Trades was “McCarthy.” The question seemed to be as to which was the most opprobrious epithet “Emissary of Gompers,” or “McCarthy.” The decision is still pending.

THE COOKS AND WAITERS.

The first to “go out” were the cooks and waiters. One pleasant morning in May all these functionaries quietly left their posts in the leading restaurants of the city and betook themselves to the streets, where they might be seen bearing banners with defiant mottos, or assembled in front of the condemned houses advising the passing crowd not to enter, or uttering, in monotonous tones the dolorous cry of “Unfair House.” The effect was soon felt. Many of the leading restaurants were closed for several days and all were much crippled. Large numbers of lesser houses accepted the Union terms and displayed its card. Things looked well for the strikers. Men, and women too, did picket duty bravely. Non-union waiters were persuaded to join the Union, and there was talk of calling out the hotel hands also. The President was about to visit the City and unbiased observers were of the opinion that, if the Labor Council stood firm (there was no fear of the strikers themselves), something might really be won. For in the face of the great crowd of enthusiasts which followed the President’s train, the hotels and restaurants would be at the mercy of the strikers.

A wail of woe went up through the length and breadth of the City, “Great California would be disgraced!” “What would the President think?” “What would the Easterners say?” “Think of the money lost to the State by driving away its visitors!” The cry of “Unfair House” was met by a counter cry of “Unpatriotic!” “Unpatriotic!” “Un-American!” The strikers faltered. Your correspondent moved partly by hunger (seeking instruction concerning union restaurants), and partly by thirst (for information) had made the acquaintance of certain of the pickets and leaders, and was in a fair position to study the strike. One morning, in search of breakfast and information, my attention was called to the fact that Dennett’s restaurant, though without the Union card, was free from pickets. Hastening down the street I accosted a woman guard. “Why is Dennett’s restaurant left unpicketed?” demanded somewhat brusquely. “Why you see,” she answered calmly, without a symptom of shame, “you see they pay pretty good wages, and they are pious people, you know.” I did know, and I knew also how hopeless is the struggle where the fighters know not for what they strive. Turning to a man who arrived at that moment wearing the Union badge, I repeated the question. The man had the grace to be ashamed. His reply was somewhat incoherent, ending with “They’re all right. You can eat there if you want to,” he added generously. I did not want to, but went, nevertheless, and was soon seated at a clothless table in a crowded room the walls of which were hung with appropriate texts from the Scriptures. Just in front of me was suspended, as an aid to digestion, the awful legend “Be sure thy sin will find thee out.” My sin having already “found me out,” I was not so much affected by the direful threat as kindly friends might be led to suppose, and soon turned my attention to the cheerful looking waiters in attendance. They spoke without restraint, for their pious hearts were full of triumph at having beaten the strikers. In a short time it was rumored that the Labor Council was a patriotic American Organization, and that the strike would not be pressed to extremes until after the President’s visit. So the moment came and went.

THE NATION’S CHIEF.

The President certainly chose an inopportune hour for his visit to the Golden City. The waiters were still picketing the streets. The Carriagemakers were in a turmoil about something. The Butchers were threatening. And worst of all the long-dreaded Steel and Iron strike was about to be precipitated here. Moreover the much-boasted climate “went out” in sympathy, and the rain fell in torrents. But the citizens were equal to the occasion. Large chromos of the President accompanied by the word “Welcome” done in horribly artificial flowers, appeared in all the saloon windows and over the doors of the corner groceries. Innumerable little green and yellow squares of bunting were strung back and forth across the principal streets, where they hung, rain-soaked, dripping green and yellow water impartially “upon the heads of the just and the unjust.” The American flag was in evidence everywhere, drooping and sad it hung, as if the shame of the last few years wore heavily upon it. A very wet banner was strung from the Labor Bureau window bearing the inscription “Welcome To Our President.” The employees of the Union Iron Works, on the eve of their strike, assembled to present their prosperity President with a gold plate. The reason for this is not known; whether it happened that the President was in dire need of a plate from which to take his daily rations, or that the steel and iron workers were troubled with a surplus, of gold, has not transpired. The strike was held in abeyance. The President mournfully paraded the dripping streets amid shouts of acclamation, while his wife lay in the rich Scott mansion, battling with death; here the brave policemen, well armed and equipped, manfully held at bay the eager throng of patriots who crowded the sidewalks and the opposite public square, clamoring for news, and occasionally making wild swoops upon the house in a vain hope of over-running the bed chamber of the sick woman and perhaps of bearing away pieces of her coverings, or, foiled in that, bits of the fence, doorstep, or of the house itself. It is a matter of speculation among local philosophers as to what would have been the effect upon the present steel and iron crisis if the patriotic citizens of San Francisco had succeeded in carrying off the whole of Mr. Scott’s residence, whittled up into souvenirs.

THE BELEAGUERED CITY.

After the departure of royal train, an epidemic of strikes set in, and to make matters worse great hordes of people who wore white caps and “wanted to know” suddenly infested the town. They were called the “Epworth League,” and were said to be Methodists, but nothing appeared in their general deportment to bear out the accusation. It was also hinted that they had come to fuse with the Social Democrats, but, as they showed no remarkable spirit of “tolerance,” the rumor died away. The floral decorations of the saloons and the colored pennants of the streets were again brought forth to decorate the town. A band of International Shooters at Marks joined the fray, so did the climate, and the grateful city groaned under the “burden of an honor unto which she was not born.” Of course the strike was held in abeyance.

STRIKE CONTINUES.

Leaguers and Shooters passed away, but the strike continued, and grew more threatening day by day. All kinds of organizations never heard of before sprang suddenly out of nothing, and each was on the point of “calling” everybody “out” of something, or, of “locking” somebody “out” of everything. The Butchers were made short work of. The Wholesale Butchers Association interfered in behalf of the retailers and ordered the Union, Card “out” of the Union shops; the cards went out. The Wholesale Butchers’ Ass’n which governs the entire meat supply of the City, now turned its attention to the Cooks and Waiters’ case, and ordered the Union cards from the restaurant windows. The cards came down and the waiters’ strike was practically though not nominally broken. This prompt action of the Wholesale Butchers’ Association, as well as the strong co-operation of the other employers, was probably intended to prove, what they so often assert, that “there is no Class Struggle.” The Draymens’ Union retaliated by refusing to work for certain non-Union houses, and talked of a sympathetic strike. They were promptly locket out.

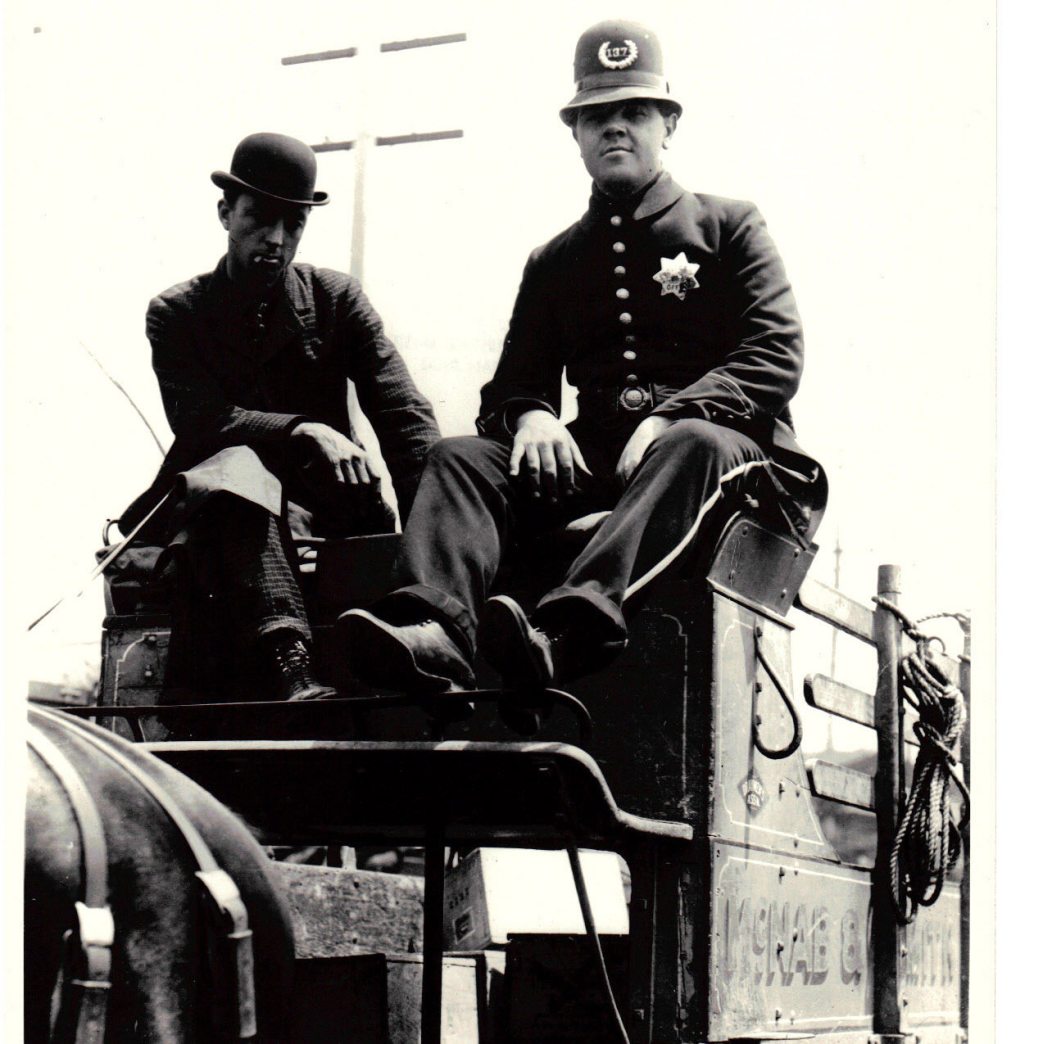

Then the real trouble began, and business of the City, already crippled by the many strikes, was, for a time, almost paralyzed. Fruit and other produce lay rotting at the wharves: ships lay idle at the docks; big warehouses were closed; an awful quiet reigned. Then a change ensued: drays driven by trembling non-Union teamsters, having policemen on the box and mounted officers riding behind, slowly moved through the streets. Crowds of maddened men thronged the sidewalks, shrieking out threats and curses, and in their train, like a bird of prey, moved the City Ambulance. Occasionally, cobble stones were hurled at the “men of law,” then clubs descended, pistols appeared, and the ambulance drew near apace. Now at last the Government arose in its majesty and performed its crowning act. Partly from the refuse of society, and partly from other sources, there were gathered together a motley crowd of miserable men who were willing to take the places of the striking teamsters: into the hands of these were put pistols with which to defend themselves. They were warned, however, “to use these arms with DISCRETION.” Think of the situation! Unknown undisciplined, half-maddened men, permitted by law to use their own discretion in firing into crowds of unarmed citizens! But to the honor of those known as the lower classes, be it said, that, in spite of the goading and tempting of their superiors, very little shooting has taken place, and so far, considering the circumstances, wonderfully little rioting.

On the morning of July 30th, the City Front Federation ordered a general strike on the docks of San Francisco and neighboring ports. The scene of the strike was shifted to the waterfront. The port was almost closed. Disorder increased. The Mayor and corporation rushed wildly about accomplishing nothing. The Labor Leader is glorious now; he is all things to all men. The secretary of one of the Unions expresses himself as “regretting to see Labor and Capital at war.” But, strangely enough, in spite of closed ports and closed factories, business seems to continue as usual.

“Labor Leaders Submit Proposals,” “Negotiations of Peace with Modified Proposals my Labor Council,” “Strike About to be Terminated Through Negotiations of Principal Citizens,” so read the headings of the newspapers from day to day. But, in spite of “modified proposals,” peace comes not, for the very obvious reason that the secret society called “The Employers’ Association,” pays absolutely no heed to these “Proposals” and “Negotiations.” It stands serene above the heat of vulgar conflict. On August 6th thousand teamsters were called out, a somewhat ominous move, as there is considerable building going on in the city. Things began to look darker. Non-Union men are beaten by strikers and strikers are shot at by non-Union men. The clubs of the policemen and their friend, the ambulance, are in more frequent use. The Mayor and corporation are indefatigable. The Governor arrives. The capitalists stand serene. Two days later. the Firemen of the Steamship Company are called out, most ominous of all. It looks as if the shipping might be completely held up.

The Chamber of Commerce calls upon the Mayor to issue a proclamation against the strikers and demands that the militia be “called out.” The Board of Trade echoes the request. The Labor Leader ascends to lofty heights of eloquence and popularity. The Mayor consults, the Governor and the Governor consults the Mayor. Both think of the coming election and their patriotic hearts swell. The capitalists rest tranquil still. The greater part of the vast crowd of locked out and striking men are very quiet. However, there is a light in their tired, blood-shot eyes, and stern, patient lines about their hardened mouths which speak well for the future. Some time they will understand.

NATURE OF THE EPIDEMIC.

The significance of this crisis is clear. These are not ordinary strikes for “less hours,” “more pay,” etc. This is the beginning of the death struggle of the “pure and simple” Unions. The employers are banded together, a compact, class conscious body, sure of victory. The workers also, setting aside the squabbles of their leaders, may be said, to stand together. But the issue is clear. In spite of the false cry of the fakir, all honest observers know that the workingman must lose. Even a temporary success can avail him nothing. The day of the “pure and simple” Union is over.

THE SOCIALIST LABOR PARTY.

Calm amid the general disorder the loyal men of the S.L.P. are constant in their work. The new headquarters at Howard street are open night and day, and numbers of disillusioned strikers seek sympathy and instruction there. Street meetings are largely attended and are marked by an order and discipline that stands out in strong contrast to the surrounding chaos. There will be a large harvest for the S.L.P. when this awful hour is passed.

JANE C. ROULSTON.

New York Labor News Company was the publishing house of the Socialist Labor Party and their paper The People. The People was the official paper of the Socialist Labor Party of America (SLP), established in New York City in 1891 as a weekly. The New York SLP, and The People, were dominated Daniel De Leon and his supporters, the dominant ideological leader of the SLP from the 1890s until the time of his death. The People became a daily in 1900. It’s first editor was the French socialist Lucien Sanial who was quickly replaced by De Leon who held the position until his death in 1914. Morris Hillquit and Henry Slobodin, future leaders of the Socialist Party of America were writers before their split from the SLP in 1899. For a while there were two SLPs and two Peoples, requiring a legal case to determine ownership. Eventual the anti-De Leonist produced what would become the New York Call and became the Social Democratic, later Socialist, Party. The De Leonist The People continued publishing until 2008.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-slp/010831-weeklypeople-v11n22.pdf