Who we are is, in part, how we define ourselves and how others define us. Language matters and names matter. Getting to grips with changing understandings of words and their meanings is part of getting to grips with changes in the society those words come out of. No definitions are as fraught, as inexact, and as obfuscatious as those used to define ‘races’ which do not exist biologically but socially. Here, Domingo interrogates ‘Negro’ and ‘colored’ in 1919.

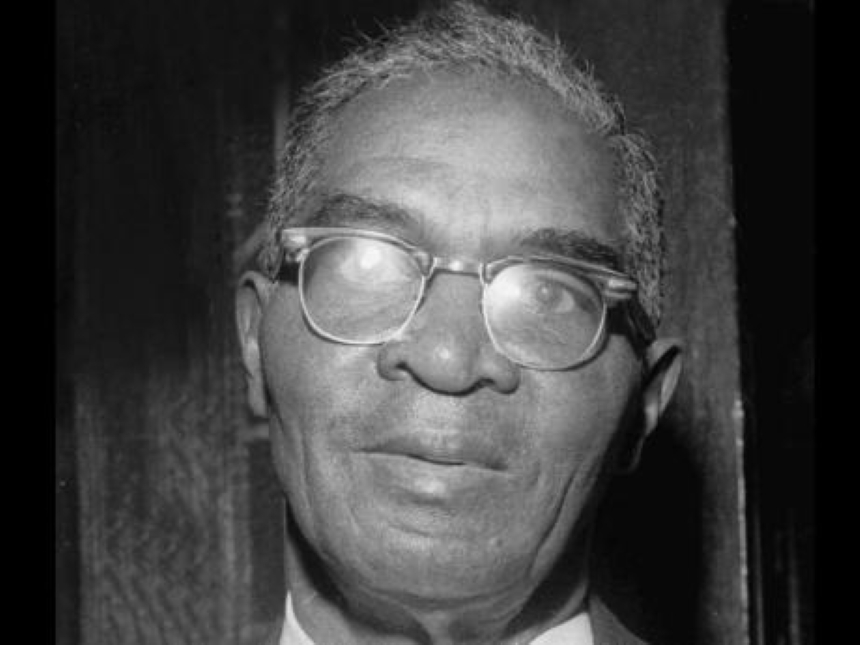

‘What Are We? Negroes or Colored People?’ by W.A. Domingo from The Messenger. Vol. 2 No. 5-6. May-June, 1919.

The discussion as to what should be the racial cognomen of the composite people of Negroid descent living in the Western world is not a new one, but has been a moot question for nearly fifty years. This discussion, strangely enough, has always been waged among the people in question themselves, and while arguing the (to them) momentous matter, the white race, which controls the literature of the world, has gone its way placidly, fixing the term according to local usage or the particular language.

But among the disputants considerable bitterness and acerbity of feelings have been engendered, which in the long run have only helped to make a breach in the ranks of a people who, despite their foibles and intra-racial distinctions, are destined by the dominant white man for a position of social inferiority. In other words, while we are fighting among ourselves over inconsequentials, the Caucasian keeps his determination fastened to the more important matter of a fixed relationship between himself and us. However, as the question seems to disturb Negro minds so much and having a definite opinion on the matter, we are treating it editorially without importing either personality or petty antagonisms into the subject. According to modern ethnologists, the human family is capable of two main divisions, viz., the colorless race and the colored races. This division is arrived at from a purely scientific standpoint. White, as any scientific book or any dictionary proves, is not a color, but is the negation of all colors, and since there is no pigmentation in white people, science correctly regards them as being the colorless race. On the other hand pigment is to be found in the skins of all the colored races whether it be yellow, Mongolian; black, Negro; red, Indian, or brown, Malay. From these major divisions, subdivisions are made, as for instance among the Caucasians, who are classified as Latins, Teutons, Slavs, etc. It is, therefore, easily seen that the term colored can with equal exactness be applied to a Chinese, a Nubian, an Apache or a Hindu. But the term colored has a special as well as a general usage. When the Kaiser is trying to unite the white people of the world, he refers to the bogey of the colored races uniting; when a person refers to a man of Negroid extraction in the United States, he speaks of a colored man, but that conveys to the hearer’s mind no idea as to the man’s actual color; but in the West Indies when the word colored is used in statistics or in describing a person, the understanding is that it refers to a person of visible white and black ancestry. Hence the term has three meanings:

The first meaning is scientific, the American meaning is vague and interchangeable with Negro, while the West Indian meaning is definite if inappropriate. What the West Indian use of the word really implies is that a colored person of white origin but who has been “colored” because of an infiltration of non-white blood, and, but for this coloration, such a person would be white. In other words, the original use of the word came from the white man’s reluctance to admit into his racial group anyone who is not altogether white. But this terminology is weak, for by the same process of reasoning, a person of Hindu-Caucasian parentage is a “colored” person, because such a person has an infusion of some kind of pigment into his otherwise colorless self. But out in India such persons have a distinct group name, one that connotes both their social status and their origin Eurasian. The same thing is also true of the hybrid of Indian and white in Brazil; they are called Mestizo, and not colored. There is this that can be said, though, of the West Indian usage. It is possible of continued acceptance and currency despite its obvious weakness, because the people so classified have become a more or less exclusive or distinct group with definite color and group interests, which fact makes the term colored one of value to them. The average West Indian of visible white admixture would be insulted to be called a Negro, because he realizes that that word connotes, in that country, a status lower than that connoted by the word colored. Hence, the clinging to an ethnologically vague and philologically inexact terminology. In the United States the situation is different, as there is no material or social gain in the use of either term. Whether a person is called colored or Negro, the dominant white man has a fixed status for that person.

If a man applies for a position and refers to himself as colored, it does not insure him greater possibility of success over the other applicant who refers to himself as a Negro. The two terms are used interchangeably, as both connote to Negroes and Caucasians in America, the same social, civic and industrial destiny. When either colored or Negro is used, it means any person in America who is not a Mongolian, an Indian or a Caucasian. And if he hasn’t on his native robes, it may even include a Hindu!

Both the words Negro and colored are terminological inexactitudes in so far as they refer to the composite millions of America; for a person one-eighth black is more a “colored” man than is the person who is one-eighth white a Negro. The so-called colored or Negro race, so far as the Western world is concerned, is neither black, yellow nor brown; but a composite people carrying in their veins the blood of many different types of the human family. What holds them together is the pressure exerted from the outside upon them by a dominant and domineering stronger race. This pressure has produced oneness of destiny and for that reason the “race” is developing a sentiment and consciousness of unity. Working from the inside is a centrifugal force that tends to disrupt, but stronger than that is the centripetal force exerted by the white man. The Caucasian has said that if a man has one-sixteenth black blood, such a person is black. While this is an absurdity in logic, still it is a fact in practice, hence such a person has no choice but to accept the name given to the black race, a little of whose blood flows in his veins. To do otherwise would be to proclaim a longing to be included in a race that despises him. Of the two terms “colored” and “Negro,” the former is the weaker, as it too loose, too inexact and means nothing specific in America; while the latter is generic and is reinforced by a history that is worthy of pride. The word colored, as apart from the people called “colored,” connotes shame and implies an insult. Besides, with what kind of logic could anyone insist that such an indefinite adjective as colored should be capitalized? On the other hand, the generic term Negro is gradually being capitalized because the word designates a racial group and not a particular color, and it would be absurd in speaking English to designate color by saying “a Negro hat,” but it would be eminently correct to refer to “a colored hat,” meaning a hat that is not white.

The word Negro is never used to describe skin color, but rather to fix racial affiliation; while a majority of Negroes are black, nevertheless even in Africa itself, there are yellow Hottentot, brown Zulu and ebon-black Nubian, all of whom are generally grouped as Negroes.

Whenever color descriptions are being made, the race name. is used as a noun and is preceded by a distinguishing adjective thus a brown-skinned Negro, a yellow Negro or a black Negro. Nor is it correct to think that all black people are Negroes, as the supporters of the word colored unconsciously imply, for there are black Hindus with aquiline features, black Arabs and black Jews. And conversely all so called Negroes of Africa, even if black, have not the other alleged Negro characteristics; for there are aquiline featured Man-dingoes with curly hair on the West Coast, and straight haired black Somali on the East Coast, while as already pointed out, there are yellow and brown Kaffirs with kinky hair in South Africa. These facts make the conclusion unavoidable that the word Negro covers, as applied to Africa, a people of varying external physical characteristics.

Even as the word Mongolian includes Tartars and Chinese, and Japanese who are of various degrees of mixture of Chinese, Malays and the aboriginal hairy Ainus of their island kingdom, and the word Caucasian includes blonde and “black” Germans, pigmented Spaniards and South Italians and red-headed Celts the word “Negro” can include all the people of African blood in this country who are, because of that blood, given the same ethnological classification. It might be permissible to use the indefinite, word colored as a more or less general term, or as a colloquialism, but as a specific racial designation it is fatally weak, as it is not on a par with Malay, Caucasian, Mongolian or Indian; nor is it as terminologically precise as Eurasian or Mestizo; nor is it specific in fixing mixture or racial types as mulatto, quadroon, zambo or octoroon: Ethnologically, anthropologically and terminologically the word colored cannot stand the test of even a casual examination.

Many persons object to the Negro because they hate its corrupted form “n***r.” But have they ever stopped to think that any word in any language is susceptible of being debased into a corrupted term of contempt? What word would they suggest that is ethnologically exact and yet would be free from being corrupted? The term “n***r” lives largely because of the careful nurture given to it by Negroes themselves. White people can hardly be blamed for using the objectionable corruption when Negroes are the principal peddlers of the term. And what does “n***r” mean? According to the dictionary it is “a term of contempt applied to Negroes,” just as the terms “cracker” and “greaser” are terms of contempt applied to certain other peoples. Will white people stop calling Negroes “n***rs” because Negroes refer to themselves as colored? That is too childish for belief.

No one has ever heard of any agitation on the part of the natives of Japan to change their national name of Japanese to something else because of the use of the, to them, offensive abbreviated corruption “Jap” by the English speaking world. Instead, they have by their achievements made the words “Jap” and “Japanese” synonyms of prowess, daring, energy and progress–synonyms that are respected and feared by all races of mankind.

Another objection advances is that the word Negro connotes slavery, but since colored and Negro are synonyms in America, how can one word connote something which the other does not connote? This objection is puerile.

Every one of the other races has a generic race name and since the composite gets its present status from one branch of its origin, it seems but sensible to accept the generic term that specifically designates that branch. Unless they can control American literature, it will be utterly impossible for Negroes to obliterate the word Negro. And the word is more worthy of living than the vague substitute offered. Instead of fighting a windmill and doing the futile, energy-dissipating thing, Negroes should concentrate upon demanding that the word Negro be capitalized in the literature of the English language even as its fellow generic terms Malay, Mongolian, Caucasian and Indian are capitalized. No amount of exclusion from racial newspapers will kill the word, for although no Negro newspaper is so shameless as to use the word “n***r” still that word has great currency among Negroes and is still to be found in the dictionary! Negroes can do better than fritter away their energy on non-essentials, and start in right now to give prestige to the word Negro, first, by capitalizing it and next by deeds that any race would be proud to have connected with its name.

To sum up: the word “colored” is objectionable because, first, it is philologically weak; second, it is ethnologically inexact; third, its origin is not pleasant; fourth, it tends towards division inside the “race”; fifth, it has comparatively no history; sixth, it cannot be capitalized; seventh, it is a makeshift.

The word Negro, on the other hand, has all the qualities lacking in colored, and is the word, more or less, in one or other of its forms incorporated into all modern languages.

In the absence of a nomenclature that is satisfactory to all types of so-called Negroes or colored people in America, the word Negro should stand, and it is for the people so designated to use all their influence to see that their race name is lifted from the same literary status as pig, monkey and dog, to the level of other race names, and be spelt with a capital “N.”

The Messenger was founded and published in New York City by A. Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen in 1917 after they both joined the Socialist Party of America. The Messenger opposed World War I, conscription and supported the Bolshevik Revolution, though it remained loyal to the Socialist Party when the left split in 1919. It sought to promote a labor-orientated Black leadership, “New Crowd Negroes,” as explicitly opposed to the positions of both WEB DuBois and Booker T Washington at the time. Both Owen and Randolph were arrested under the Espionage Act in an attempt to disrupt The Messenger. Eventually, The Messenger became less political and more trade union focused. After the departure of and Owen, the focus again shifted to arts and culture. The Messenger ceased publishing in 1928. Its early issues contain invaluable articles on the early Black left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/messenger/1919-05-06-may-jun-Messenger.pdf