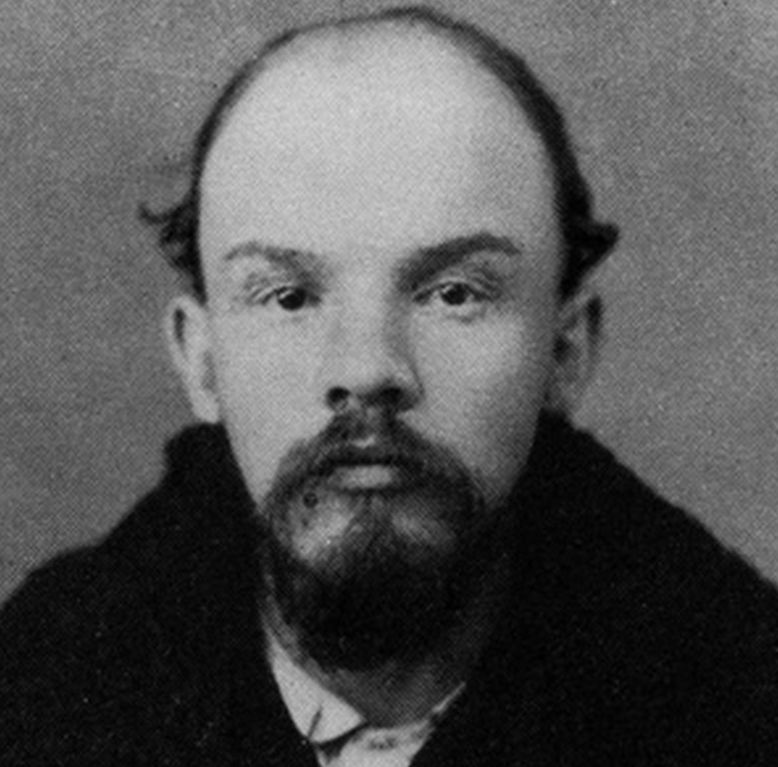

Lenin speaks to the police killing of workers on strike at the Obukhov steel plant outside of Moscow on May 7, 1901.

‘Another Massacre’ (1901) by V.I. Lenin from Collected Works. Vol. 4. International Publishers, New York. 1930.

APPARENTLY, we are now passing through a period in which our labour movement will once again lead precipitously to acute conflicts, which terrify the government and the propertied classes, and rejoice and encourage the Socialists. Yes, we are rejoiced and encouraged by these conflicts, notwithstanding the numerous victims that fall by the hand of the military, because the working class is proving by its resistance that it is not reconciled to its position, refusing to remain in slavery, or to suffer violence and tyranny in silence. Even in the most peaceful times, the present system inevitably calls for great sacrifices on the part of the working class. Thousands and tens of thousands of men and women, toiling all their lives to create wealth for others, perish from starvation and constant under-feeding, prematurely die from diseases caused by the horrible conditions under which they work, and the wretched conditions in which they live and overwork. He who prefers death in the open struggle against those who defend and protect this horrible system, rather than the lingering death of a crushed, brokendown and submissive hag, deserves the title of hero a hundredfold. We do not say that scuffling with the police is the best form of struggle. On the contrary, we constantly tell the workers that it is in their interests to conduct the struggle in a more calm and restrained manner, and to strive to direct all discontent in support of the organised struggle of the revolutionary party. But the spirit of revolt now reigning among the working class is the principal source from which revolutionary Social-Democracy obtains its strength. In view of the environment of violence and oppression in which the workers live, this spirit cannot help breaking out from time to time in the form of desperate battles. These battles rouse the widest strata of the workers, who are oppressed by poverty and ignorance, to conscious life and stimulate in them a noble hatred of the oppressors and enemies of liberty. That is why the news of the massacre that took place at the Obukhov Works1 on May 7 causes us to exclaim: “The workers’ uprising has been suppressed; long live the workers’ uprising!”

There was a time, not very long ago, when workers’ rebellions were rare exceptions, called forth only by very special circumstances. Now things have changed. A few years ago industry flourished, trade was brisk and there was a great demand for workers. Notwithstanding this, the workers organised a number of strikes in order to improve their conditions of labour. The workers realised that they must not lose the opportunity offered by the circumstances that the employers were making exceptionally high profits, that it was therefore easier to compel them to make concessions. But the boom has given way to depression. The manufacturers cannot sell their goods; their profits have declined; the number of bankruptcies has increased; production is being cut down; workers are being discharged wholesale and flung on to the street without a crust of bread. The workers have now to put up a desperate fight, not for the improvement of their conditions, but for the maintenance of the old conditions, and to resist the attacks the employers are making upon them in forcing them to bear their losses. Hence, the deepening and widening of the labour movement. At first the struggle was waged in exceptional and isolated cases. Then, during the industrial and commercial boom, followed a period of unceasing and stubborn battles, and, finally, a similar unceasing and stubborn struggle in the period of depression. Now we may say that the labour movement has become a permanent feature of our public life, and that it will grow no matter what the circumstances may be.

But the passing of the boom, and the coming of the crisis, will not only teach our workers that united struggle has now become a necessity for them, it will also destroy the harmful illusions that began to be fostered in the period of the industrial boom. In some places, the workers were able by means of strikes to compel the masters to make concessions with comparative ease, and the significance of this “economic” struggle began to be exaggerated; the workers began to forget that trade unionism and strikes, at best, can only enable them to obtain slightly better terms of sale for their commodity—labour power. Trade unions and strikes become impotent when, owing to depression, there is no demand for this “commodity.” They are unable to remove the conditions which convert labour power into a commodity, and which doom the masses of the toilers to poverty and unemployment. To remove these conditions, it is necessary to conduct a revolutionary struggle against the whole existing social and political system, and the industrial crisis will compel many, many workers to realise the truth of this.

Let us return to the massacre of May 7. We report below the information we have received concerning the May strikes and the unrest among the St. Petersburg workers.2 Here we shall examine the police report of the massacre of May 7.3 Lately we have learned to see somewhat through government (and police) reports of strikes, demonstrations and the conflicts with the police. We have collected enough material to enable us to judge of the accuracy of these reports, and sometimes we are able to catch glimpses of the fire of popular indignation burning behind the smoke screen of police falsehoods.

“On May 7 [says the official report] about two hundred workers, employed in the Obukhov Steel Works, in the village of Alexandrovsk on the Schliisselburg Highroad, stopped work after the dinner recess, and in the course of their interview with the chief of the Works, Lieutenant-Colonel Ivanov, put forward a number of groundless demands.”

If the workers stopped work without giving the required two weeks’ notice—assuming that the stoppage was not caused by illegal acts committed by the employers, which is not infrequently the case—then even according to the Russian laws (which recently have become more stringent against the workers), they have merely committed a common offence liable to prosecution before a magistrate. But the Russian government is making itself more and more ridiculous by its stringency. On the one hand, laws are passed which create new crimes (for example, willful refusal to work, or assembling in crowds, resulting in damage to property or in resistance to armed force), the penalties for strikes are increased, etc., while on the other hand, the physical and political possibility of applying these laws and imposing penalties that are reasonable, are removed. It is physically impossible to prosecute thousands and tens of thousands of men for refusing to work, for strikes, or for “assembling in crowds.” It is politically impossible to try each separate case, because, however carefully the judges may be selected, and no matter what efforts are made to avoid publicity, still, it will remain a semblance of a trial, and, of course, not a “trial” of the workers, but of the government. Thus, the criminal laws passed for the special purpose of facilitating the government’s political struggle against the proletariat (and at the same time to conceal its political character by “reasons of state” in regard to “public order,” etc.) are unavoidably forced into the background by the direct political struggle and open street battles. “Justice” throws off the mask of majesty and impartiality, and turns to flight, leaving the field to the police, the gendarmes and Cossacks, who are greeted with a hail of stones.

Take the government’s reference to the “demands” of the workers. From the standpoint of the law, cessation of work is a misdemeanour, irrespective of the character of the demands put forward by the workers. But the government has thrown away its chance of standing on the law which it recently passed, and now tries to justify the punishment inflicted with “the means at its disposal” by declaring that the demands of the workers were unjustified. But who were the judges in this affair? Lieutenant-Colonel Ivanov, the assistant chief of the Works, i.e., one of the officials against whom the workers complained! It is not surprising, therefore, that the workers retort to such explanations by throwing stones!

Thus, when the workers poured into the street and held up the street cars, a real battle commenced. Apparently the workers fought with all their might for they twice succeeded in beating off the attack of the police, the gendarmes, the mounted guards, and the armed factory guard,4 notwithstanding the fact that they were armed only with stones. It is true, if the police reports can be believed, “several shots” rang out from among the crowd, but no one was injured by these shots. Stones, however, fell “like hail,” and the workers not only put up a stubborn resistance, but displayed resourcefulness and ability in adapting themselves to conditions and selecting the best form of fighting. They occupied the neighbouring courtyards and from over the fences poured a hail of stones upon the Tsar’s Bashi-Buzuks, so that even after three volleys had been fired, as a result of which one man was killed (only one?) and eight (?) wounded (one died on the following day), even after these volleys had been fired and the crowd had fled, the fight still continued and a company of the Omsk Infantry Regiment had to be called out to “clear the neighbouring courtyards of workers.”

The government emerged victorious. But victories like these will bring the government nearer to its ultimate defeat. Every fight with the people will tend still more to rouse the workers to indignation and stimulate them to fight; it will bring to the front more experienced, better armed, and bolder leaders. We have already had occasion to discuss the plan which these leaders should strive to carry out. We have on more than one occasion pointed to the necessity for a sound revolutionary organisation. But in connection with the events of May 7, we must take care not to lose sight of the following:

Much has been said recently about the impossibility and the hopelessness of street fighting against modern troops. This has been particularly insisted upon by the wise “critics,” who have advanced the old stuff of bourgeois science in the guise of new, impartial, scientific conclusions, and in doing so distort what Engels said, with reference only to the temporary tactics of the German Social-Democrats. And even then he said this with certain reservations. But even isolated battles demonstrate how absurd these arguments are. Street fighting is possible. It is not the position of the fighters, but the position of the government that is hopeless if it has to deal with larger numbers than those employed in a single factory. In the battle on May 7, the workers had no other weapons at their command than stones, and, of course, the mere prohibition of the governor of the city will not prevent them next time from securing other weapons. The workers were unprepared, and numbered only three-and-a-half thousand. Nevertheless, they repelled the attack of several hundred mounted guards, gendarmes, city police and infantry. Did the police find it an easy task to storm even one house, No. 63 Schlusselburg Highroad? Will it be easy to “clear” of workers not one or two courtyards, but whole blocks in the working-class districts of St. Petersburg? When the decisive battle takes place, will it not be necessary to “clear” houses and courtyards of the capital, not only of workers, but of all those who have not forgotten the atrocious massacre of March 4, who have not become reconciled with the police government, but who are merely frightened for the time being, and have not yet acquired confidence in their own strength?

Comrades! Collect the names of those killed and wounded on May 7. All the workers of the capital must honour the memory of these men, and prepare for the decisive battle against the police government for the liberty of the people!

Iskra, No. 5, June, 1901

1. A steel plant near St. Petersburg.—Ed.

2. The correspondence on the unrest and the May strikes in St. Petersburg was published in Iskra, No. 5, June, 1901, under the heading, “The First of May in Russia.”—Ed.

3. The events at the Obukhov Works were not reported in the Official Gazette, as was usually done with events of this kind, but were reported in an obscure place in the big newspapers, as for example in Novoye Vremya, May 9, 1901, without any indication of the source of the information. The reports commenced with the words: “We have received the following reports,” and then followed the text from which Lenin quotes. The report, of course, was sent to the press by the Police Department.

4. The government communication states that “the armed factory guard” were already in readiness in the factory yard,” whereas the gendarmes, mounted guards and the city police were called out later. Since when and why was an armed guard maintained in readiness in the factory yard? Was it since May 1? Did they expect a labour demonstration? That we do not know; but it is beyond doubt that the government is deliberately concealing information in its possession, which explains why the discontent and indignation of the workers was roused, and grew.–Lenin

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/details/leniniskaperiod10004vari/page/324/mode/1up