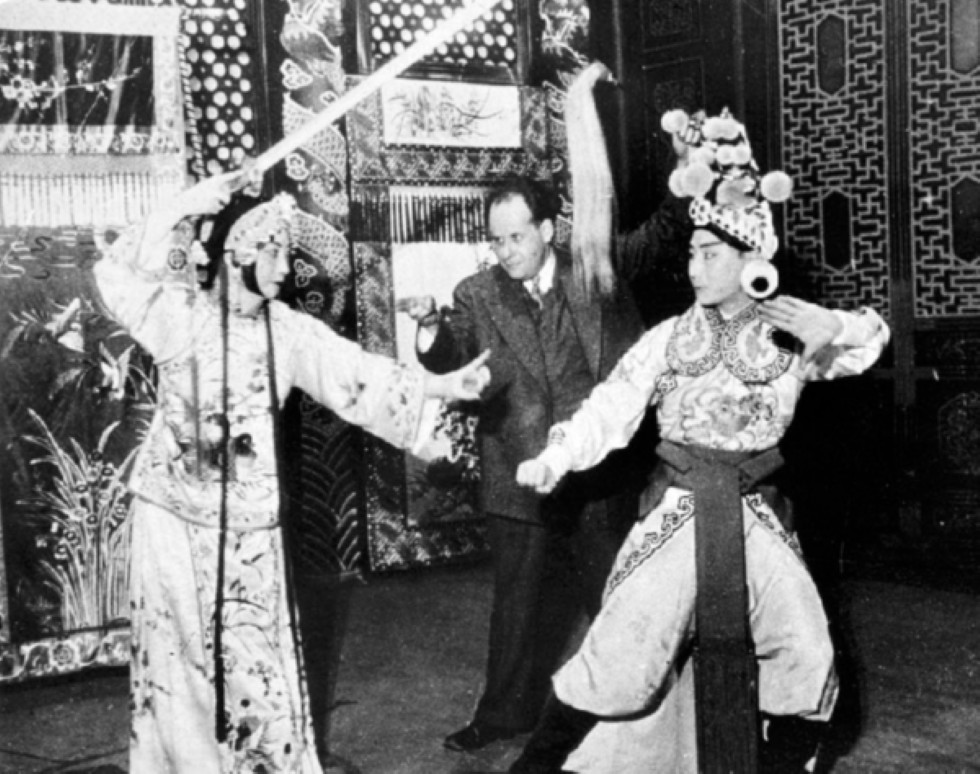

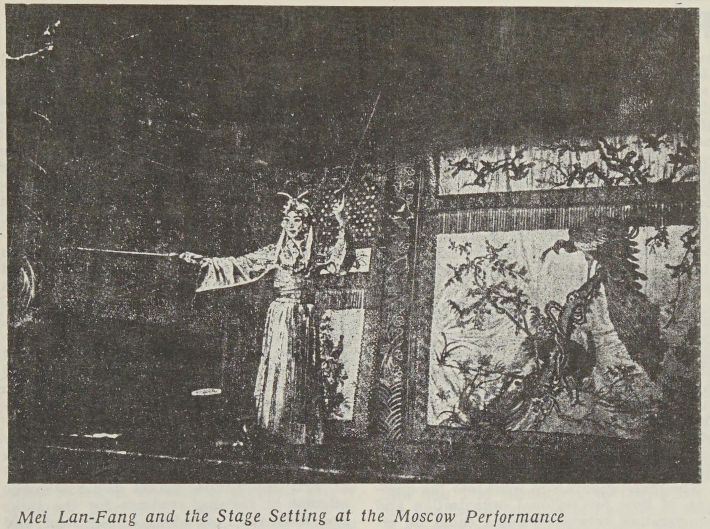

On a tour of Europe in 1935 that would bring him, and the theatrical traditions he represented, to such artists as Bertolt Brecht and the author, Eisenstein’s imagination is clearly captured by Mei-Lanang’s plays and performances.

‘Mei Lan-Fang and the Chinese Theatre’ by Sergei Eisenstein from International Literature. No. 5. 1935.

About a Noted Chinese Actor Who Visited Moscow

My introduction to the magnificent art of Mei Lan-fang was through the accounts of Charlie Chaplin, from whom I first heard an enthusiastic appreciation of the subject of this article.

I should like to begin my discussion of this artist, who has been our guest, by recalling one of the graceful, untrustworthy legends that cling about the origin of the Chinese Theatre; legends which abound in accounts of the infancy of any national theatre.

That is the legend of the siege of the town of P’int Ch’eng in the year 205 B.C. (with which is bound the legend concerning the origin of marionettes, although there are others of still greater antiquity).

The troops of the emperor took refuge in this town. They were besieged by Hunanese troops, whose commander, Mao-Tun, surrounded the town from three sides; entrusting the command of the troops besieging from the fourth side to his wife, Een-Shi. The besieged town began to feel hunger, want, and every possible privation. But the defender of the town, General Ching-Chen, succeeded in relieving it from the siege by a clever ruse. Learning that Een-Shi, the wife of Mao-Tun, was of an extremely jealous disposition, he ordered that a great number of wooden female figures, bearing a remarkable resemblance to living women, be prepared. These figures he distributed along that part of the wall which faced the soldiers under the command of the bellicose and jealous lady. By means of a clever mechanism, apparently a complicated system of strings, these figures were brought into action; dancing, moving, and executing graceful motions. Seeing them from afar, Een-Shi, naturally, took them for living women; women, moreover, of extremely seductive appearance. Aware of her husband’s amatory inclinations, she began to fear that with the taking of the town his interests would soon shift in the newcomers’ direction. This would have dealt a blow to the influence which Een-Shi exercised over her husband, and therefore, she immediately removed her troops from the walls of the town, thus breaking the ring of besiegers and saving the town.

Such is one of the legends dealing with the origin of marionettes. In due time their place was taken by actors, who long thereafter, bore the characteristic sobriquet of “living dolls.”

I mention this legend in the manner of a prefatory word to the drama which Mei Lang-fang brought to us; to his artistry, which is bound up with the best and oldest traditions of the great theatrical art of China; which in its turn is indissolubly bound up with the marionettes and their characteristic dance. To the present day this dance preserves its imprint on the originality of Chinese stage movement. Mention of this legend is also relevant in that one of its characters enters into the group of types, unfamiliar to us, which Mei Lan-fang impersonated.

That character is the woman-strategist, the woman warrior. Mei Lan-fang played the role of the war-like maiden with the same unsurpassed perfection with which he represented lyrical feminine types. Such a play is Mu-Lan in the Army, in which, playing the title role, Mei Lan-fang depicts the martial exploits of a girl who assumed the disguise of a warrior in order to take the place of her aged father in war.

The astonishing system and technique of the Chinese Theatre deserve more than a cataloguing of its conventions. They deserve at least, if nothing more, a careful consideration of its premises; an analysis of the ways of thought which produced these remarkable forms of expression. Numerous foreigners, for example, have been astonished by the fact that in Chinese theatres the spectators sit sideways, their faces directed towards long tables running perpendicularly from the end of the stage. But from the point of view of the ancient tradition, which held that the ear, and not the eye should be directed upon the stage, this is altogether proper. The theatregoer of those days went not so much to see the play as to hear it. A similar tradition once flourished and passed away in our country. It was a distinguishing feature of the Moscow Little Theatre during the period of its greatest development. Aged men still remember Ostrovski, who never viewed his own plays from the auditorium, but always listened to them from the wings, judging the excellence of the performances by the perfection with which the text was recited. Here, perhaps, is the place to mention one of Mei Lan-fang’s greatest services.

Preserving the Art of the Ancient Theatre

In the most ancient period the performance was synthesized an indissoluble bond existed between song and dance. Later a division took place. The drama began to base itself upon the vocal beginning and movement disappeared. The peculiarity mentioned above dates from this time. Mei Lan-fang has restored the most ancient tradition. Studying the ancient stage craft this great artist, scholar and connoisseur of his national culture has returned to the craft of the actor its pristine synthetic character, reviving its tastefulness and complex union of movement with music and the splendor of ancient stage robes. But Mei Lan-fang is not a mere restorer. He has successfully united the perfected forms of the old tradition with fresh, living content. He has striven to broaden its thematic range in the direction of social problems. This is noted by George Kin-lang, who brought forward from Mei Lan-fang’s repertory of several hundred plays a number of indications as to their subjects, dealing with the depressed social condition of women. Several deal with the battle against backwardness, religious superstitions and prejudices. These plays, performed in the ancient conventional style, but treating problems of contemporary characters, acquire an unusual sharpness and charm. In Mei Lan-fang’s plays the theme of woman receives exhaustive treatment. Still another distinction of the artist is his ability to impersonate a variety of feminine types. A narrow specialization, confinement within the limits of one type, characterize the average actor. Mei Lan-fang handles practically all types with equal perfection.

Not stopping there, he has brought a number of improvements to the traditional treatment of these types, all in complete and strict uniformity with their style. He impersonates equally well both basic stage feminine types, presenting the virtuous and distressed type, the lively, quick-witted, lightheaded girl, as well as the evil-doer and intriguer. In general six main stage types are known to tradition.

1) Cheng-Tan—the type of good-hearted matron, faithful wife, virtuous daughter.

2) Huan-Tan—generally a younger woman than the above type; loose in her ways, sometimes a house maid. In general, Cheng-Tan is a positive and virtuous type, and lyrical and melancholy elements predominate in her singing, while Huan-Tan is a young woman of doubtful character. Her role constitutes the play’s center of gravity, in the liveliness and dash of the stage play.

3) Kuem Men-Tan—an unmarried girl, likewise a graceful, elegant and virtuous type.

4) Vu-Tan—unlike the above mentioned type; this is a heroic and warlike character—a woman-warrior and strategist.

5) Tsai-Tan—the heartless woman; an intriguer, often treacherous; a housemaid. Endowed with stage beauty, she is negative in her actions.

6) Lao-Tan—the type of aged woman; often the mother. Played with great feeling. The most realistic character of all.

In all these names occurs the hieroglyphic, denoting “Tan.” Ordinarily this word is translated, “performer of the woman’s role” or “he who impersonates women.” Such a translation, however, does not at all give the implied meaning. The above cited Kin-lang strongly emphasizes that this denotation has a quite specific sense, excluding completely the conception of a naturalistic reproduction of feminine characters. It primarily denotes an extraordinarily conventional structure, which aims above all to create a definite, esthetically abstract image, stripped to the utmost of all that is incidental or personal. It aims to produce in the spectator esthetic satisfaction through the depiction of the idealized, abstract, generalized qualities of feminine charm. The naturalistic representation or reproduction of ordinary, life-like women is not part of its purpose. Here we come across the main peculiarity of the Chinese Theatre. Realistic (in its special sense) in content, treating not only the universally known episodes of history and legend, but also social, everyday problems, the Chinese Theatre is in form highly conventional, from the subtlest elements of character treatment to the most insignificant stage details. In fact, if we take from any description of the Chinese Theatre an inventory of its conventional elements, we shall see that each element bears that same imprint of original interpretation which is noted by Kin-lang in commenting on the approach to the impersonation of women’s roles. “Each situation, each object is immutably abstract in its nature and often symbolic; pure realism is absent from the performance, and realistic situations are banned from the stage.”

Symbolism in the Chinese Theatre

I shall cite a number of examples from the traditional attributes.

An oar may by itself signify an entire boat.

Ma-Pien—a horse whip. An actor holding a horsewhip in his hand is conceived to be riding on horseback. A brown horsewhip signifies a brown colored horse. White, black, fiery-colored whips signify horses of the corresponding color. The actions of mounting and dismounting from the horse are rendered by set, conventional gestures.

Ling-Chien—The messenger’s arrow. In the past, when the military leader dispatched a messenger, he gave him an arrow as confirmation of the authenticity of the news which he bore. This action also signifies that the order should be executed with the speed of an arrow. From here the formula of handing over an arrow in dispatching a decree became a stage convention.

I could continue this enumeration for a long time.

More interesting are those examples where an object can signify any number of things, depending upon its application. Such, for example, are the table, the chair, and the whisk of horsehair. Of these, the table, or Cho-Shzu, more than any other object, can signify the most unlike things. Now it is a tea-shop; now a dinner-table; now a court room; now an altar. When it is necessary to depict a character ascending a mountain or climbing over a wall, the same table is brought into service. The table is used in all positions—upright, on its side, upside down. The same is true of the chair, Cho-Shzu. When the chair lies on its side, Tao-i, it signifies that a man is sitting on a cliff, on the ground, or in an uncomfortable position. If a woman is ascending a mountain, she stands upon a chair. Several chairs together denote a bed. Still broader are the functions of the Ing-Chen—the whisk of horsehair. On the one hand it forms an attribute of semi-divine condition. The right of possessing it was limited to gods, demigods, Buddhist monks, Taoist priests, heavenly beings and souls of various categories. On the other hand, in the hand of a housemaid, it could sweep the dust from furniture, serving as an object of domestic use. Descriptions of its functions end with the comprehensive statement: “In general, the whisk is extensively utilized in the Chinese Theatre, and may denote any quantity and any kind of objects.”

The Chinese theatre, so to speak, may be considered as the bringing to its limits of one of these aggregates of features which are peculiar to any production of art. That aggregate of feature which in its totality determines the essence of its artistic production, is its imagery.

The experience of Chinese Art in this field should give us much material for study and the enrichment of our artistic methods.

Translated from the Russian by B. Keen

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1935-n05-IL.pdf