Dobb defends his conceptions of Marxism as a unitary whole, only to be verified in practical activity, against the propensity of what he calls the new ‘English Marxists’ to focus on Marx’s ideas in relation to particular, largely theoretical, questions or scientific schools.

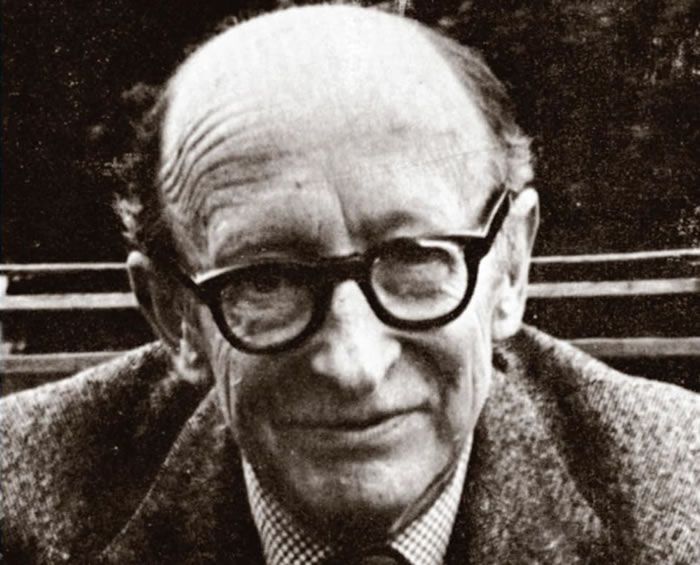

‘Marxism and the Crisis’ by Maurice Dobb from New Masses. Vol. 8 No. 3. September, 1932.

Arising from, and the product of, the general crisis of capitalism today, there are two crises, or subordinate phases of that crisis—a crisis of thought and a crisis of politics. The crisis of politics shows itself in this country, and not alone in this country, in a complete break-up of all the old party groupings and a blurring of the old political issues. True, the old party structures and the old party creeds still continue and still flourish with their banners and their slogans. Their mock tourneys still delude the masses and carry their eyes away from the real issues. But these banners and these slogans are dead: they indicate issues which are dead and past and bear no live relation to what are the real contemporary issues. If one looks for a historical parallel, be it only a superficial one, it is, I think, to be found in the thirties of last century, when the old Whig and Tory issues were an anachronism. The Party structures, as shells, remained; but they had no meaning; and the younger Tories and Whigs had more in common with one another than they had with the older members of their own parties. Then it was a prelude to the triumph of Liberalism as the creed of the triumphant bourgeoisie. Today it is the prelude to Fascism, as the last reserve of a decadent bourgeoisie.

Included in this destruction of old landmarks is the issue between Individualism and Socialism as it has been known in England. This fact was pointed out by the Liberal Yellow Book a few years ago: the very development of Capitalism, it stated, had rendered the old issue obsolete. Monopoly-capitalism has developed through various half-way stages to the public and semipublic corporations, which are as far removed from the small-scale competitive capitalism of the nineteenth century as any Fabian of the ‘nineties’ could have wished. The issue between laissez-faire and State control has become, not a matter of principle, but a question of degree, of expediency; and today the question of Planning cuts right across all the old party boundaries. Everybody is talking Planning—from Sir Basil Blackett to Mr. Fenner Brockway. The issue of the future seems not to be an issue between planning and not planning, but merely how much planning and in what form. Belief in planning is irrespective of the old sort of political alignment: it has ceased to be a political issue in the old sort of politics. (Although that is not to say that capitalism will be able to introduce successful planning; it clearly cannot do so in a complete enough form). The National Socialists are right: they are the logical outcome of Labor Party Socialism: the only issue left on this plane is a National issue, above classes.

The crisis in thought is less easy to detect; but is none the less apparent, even if it takes more variegated forms. On the one hand, it shows itself in a breakdown, a growing sense of insufficiency, of the older forms of English materialism: a feeling among scientists that the old rough-and-ready empiricism is not enough and a groping after some philosophical restatement. On the other hand, it shows itself in the rise of the new fashionable pseudo-philosophies, re-importing God through the “hole-in-the-atom” and showing that science, instead of being pagan and iconoclastic, can be made to decorate an altar-piece after all. More generally, this crisis in thought shows itself in a vague bewilderment: a starting to question assumptions, the very root of traditional bourgeois thought, whether it be traditional idealism or traditional materialism. In extreme forms it becomes a general bewilderment in face of universal paradox—despair in face of a world gone mad. Some get no further than bewilderment, and retreat to the seclusion of various brands of mysticism—ever the way of despair with the world. But for logical thinkers, having the resolution to cut their way through to some new synthesis, paradox itself is the bridge to new truth. Among them there arises a shrewd suspicion that if history seems to be mad when one attempts to interpret it in terms of traditional categories of thought, then it must be, not history, but one’s own thought that is wrong—that reality does not “fit” because the old categories are unfit. This realization that thought itself is a creature of history is a revolutionary one. To grasp it is to pass over from bourgeois ideology into Marxism. It is to realize that the whole basis of traditional thought rests on the assumption of certain absolute values and certain absolute intellectual categories, holding supreme for all time; and that the role of the intellectual is to soak himself sufficiently in this “intellectual heritage” as to have the gift of interpretation over things which seem paradox to ordinary men. But to regard the thought of each epoch as the product of each epoch is to see that historical change must change also the fundamental assumptions of thought: there are no absolute categories. It is to unseat this conceit of the intellectual, and to show the road of wisdom to lie in practice—in the passions of contemporary history, not the dust of ancient chronicles; in politics, not in the cloister.

As offering a new and revolutionary conception of the relation between thought and practice Marxism is becoming of growing, even primary, interest today. Equally is one led to Marxism by the facts of the political crisis, since Marxism provides the sole meaning in which Socialism can stand forth as a distinctive political creed at the present time. The reason why the importance of Marxism is not more generally or more rapidly appreciated, both as an intellectual synthesis and as an essential basis of Socialism, is partly, I believe, because so much quite elementary misunderstanding of Marxism exists.

In the first place it seems necessary to say that Marxism is not synonymous with Economic Determinism. It is not synonymous with the materialism of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; nor can it be treated as a philosophy which can be stated in a series of propositions and learned and understood as a dogma. If one is asked to summarize in a sentence the difference between Marxism and the old-fashioned Materialism, I should put it in this way: the old-fashioned issue between materialism and idealism was concerned with statements, abstractly framed and statically conceived, concerning the nature of the universe (what Feuerbach characterized as “speculative philosophy”), one saying that the world was mind and the other that the world was material substance; whereas the Dialectical Materialism of Marx is, not a meaningless dogma about the nature of a static reality, but a practical attitude—an attitude to activity; which takes as its fundamental tenet that knowledge is given in practical activity. To it all philosophical questions are meaningless, unless translatable into terms of practice: what is the efficacy of particular activities in changing the world? Especially does it eschew the old-style speculative reasoning which starts from the assumption of a purely passive individual, contemplating the world from an armchair and analyzing the stages by which knowledge reaches him of the mysterious “unknowable” thing behind the world of sensation. It denies that there can be any such thing as passive experience—the passive mind that is a spectator and no more. All experience implies activity; and questions of knowledge can only be framed in terms of an active subject, where the receiving of an experience is inseparably bound up with doing something. What seems unknowable to passive contemplation becomes knowable in the act of changing the world.

As a view of history, Marxism is not synonymous with old-style economic determinism, for the reason that it does not regard history as a process which can be interpreted in terms of continuity or be made the basis of mechanical forecast. This much it has in common with the economic determinist: it regards history as a succession of purely material events, to be interpreted in terms of concrete experience, without any “secret of history” lying behind in the realm of mystical ideas which can only be apprehended in mystical revelation. But history is not an evenly continuous process, proceeding “spontaneously” without the intervention of human purpose: it consists of a process of successive conflicts, the transition from one stage to the next taking the form of a revolutionary culmination of the conflict—a revolutionary “jump” from one epoch to another, in the course of which new historical elements emerge. In other words, history is not a mechanical process, but a dialectical process, the motivation of which consists precisely in conflict and contradiction.

Yet this “jump,” this revolutionary act of historical creation, is not something mystical; it is not something which falls from heaven or can be learned by intuitive contemplation of the verities. A chemist, in mixing certain chemicals, at a certain stage produces an entirely new element. Thereby he effects a revolution; but he does it, not as a magician, but as a scientist. He knows that the new element cannot emerge from any, but only out of one particular combination of pre-existing elements; and it is science, not mystical communion, which tells him what this necessary relationship is. Similarly, the Marxist does not believe that revolution can be effected miraculously—be invoked out of ideas which are summoned from the skies. He regards history as having a certain necessary order, in the sense that Socialism could not have been created in the mediaeval world; in the sense that a Planned Economy can be produced in Russia after a proletarian revolution, but could not be produced in capitalist Britain. Hence to the Marxist, while history is made by revolution, a particular revolution can arise only at a particular stage of development—and only on the basis of a given pre-existing situation. It is in this stress on revolution as the creative force of history that Marx has his principal link with Hegel. Both regard history as a process of conflict and contradiction, its movement explicable in no other way. But for Marx history has meaning, not as an ideal process, but as a conflict of classes. History passes from one stage to the next in the form of such a class conflict, and it is out of the resolution of this conflict in the act of revolution that the new order is born. Hence Socialism arises, not “spontaneously,” not by an “organic” process of experimental adaptation, but by class struggle and the revolutionary seizure of power by the working class.

What, then, is the relation of thought to this process? What is the role of forecast and rational judgment? Clearly, there will always be, in a sense, a contradiction between the “ideal” which the revolutionary movement puts on its banners and the actual achievement it is destined to realize. This is bound to be so, for the reason that it is impossible to forecast history entirely: as we have said, history is dialectical and not mechanical and cannot be reduced to terms of mechanical forecast. To do so is to degrade the role of political activity and to fall into a vulgar, defeatist, mechanical “spontaneity.” Yet, the more the ideology of a movement corresponds to a rational scientific forecast, the more effective that movement is likely to be—the more its aims will be coincident with its practice; the more the movement will be “objectively” the same as it is “subjectively.” And this is the essential difference between “Scientific Socialism,” or Marxism, and all brands of “Utopian Socialism.” The better the chemist knows the elements he is using, the more likely is his expectation to be synonymous with actual events. The more the revolutionary is equipped with the knowledge of past history and theory and at the same time has an actual detailed, concrete knowledge of the elements of the contemporary situation in which he works, the more efficacious is his policy likely to be. In this truth is explained the fundamental feature of Marxism: the unity of theory and practice. On the one hand, the politician making contemporary history is entirely blind—is an entire opportunist—unless he is equipped with a Marxist understanding of past history. On the other hand, the student of history remains entirely academic and is asking and answering purely meaningless questions, unless “the questions he puts to history” and the categories in which he interprets history, are those which current political activity (i.e., contemporary history) afford. Marxism is, therefore, essentially an attitude towards political activity, based on a particular conception of the relationship between thought and current practice. As such, it must necessarily be accepted in the whole, or rejected. One cannot split it up into sections; one cannot study separate parts of it in isolation, since its sectional parts only have meaning as parts of the whole.

Today an “English Marxism” is rapidly becoming fashionable—a sort of revised, 1932 neo-Marxism, specially adapted for English intelligences. What is characteristic of this tendency is the attempt to produce this new concoction by cutting up Marxism into sections and taking some which seem palatable and rejecting others. Because it proceeds in this way, this tendency is essentially wrong and destined to produce nothing but confusion and to hinder real understanding of Marxism and of revolutionary politics. It is especially significant that the line of division, where the “cutting” is made, usually lies along the Marxian theory of politics and the Marxian theory of the State, which are regarded as out-of-date, particularly the theory of revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat. An attempt is made to use history. But that is an impermissible way of treating Marxism, because then there is nothing left. Marxism as an attitude to contemporary history and to action is gone. As an interpretation of past history alone, it becomes degraded to a mere “economic interpretation,” forced on to the horns of the dilemma of either accepting a rigid historical fatalism or else as a guide to contemporary history—to contemporary activity—explaining precisely nothing at all. Mr. Rowse, for instance, would reject the theory of the State as an old-fashioned half-truth, inapplicable at any rate to English peculiarities; and with it necessarily goes the theory of revolutionary politics and the dictatorship of the proletariat. Mr. Murry is less explicit. Whether or not he accepts in words the Marxian theory of the State he completely fails to face up to the logical implications of the Marxian theory of politics. In his view of England, at any rate, it is precisely the implications of the State as a class instrument that he ignores; so that while he may accept physical birth as a glorious fact, he has no place for the forceps of the midwife. At any rate he casts his “Marxism” in such a “moral,” such a Spinozist, shape as to destroy all meaning in the contrast between “scientific” and “Utopian” Socialism.

But the Marxist conception of class is meaningless except with the idea of exploitation—the latter is included with the former in the same definition. Similarly, without the concept of the State as a class instrument, it is inconceivable that a class system, rooted in the exploitation of the masses by a small minority, could last out a span of more than a few years. And if the State in capitalist society is essentially a capitalist State—an organ of class domination, to perpetuate an exploiting system—then proletarian politics can be nothing less than revolutionary politics—a struggle to overthrow the exploiting system which of necessity implies a struggle against the State. Socialism then acquires its only consistent meaning, not as an issue of planning versus laissez-faire, but as the ending of class-exploitation in the only way it can be ended, namely, by expropriation of the exploiting class. And, since history does not proceed mechanically, but is framed by conscious purpose, inspired by a scientific theory, it follows that such a revolution and the eventual building of Socialism on new foundations cannot arise “spontaneously,” but must be led and guided by a revolutionary Party. Such a Party must be of the proletariat, while leading it, it must be part of the proletarian movement, in order to guide it, but it must not merely follow events “by the tail.” Hence, the primary importance in Marx’s theory of the role of a Communist Party.

It is a common fallacy that Communists are people who want to do things in a hurry, impatient people, to be contrasted with the more sober experimental sort. But the distinction is not a time distinction. Actually the Communist places a much greater stress on historical relativity than anyone else. He realizes that events have a certain order—that there is a certain order of “first things first,” and that there are other things which it is utopian to hope to attempt. For instance, he regards it as utopian to conceive the possibility of a planned economy apart from proletarian revolution as a first condition; and similarly utopian to conceive of a proletarian revolution without a whole period of preceding partial struggles, and without a revolutionary Party leading those struggles, and schooled in years of the class struggle. Communists differ in holding a particular view of history and of politics (which is the making of current history). This view is Marxism. If one is to discuss Marxism and seek to understand it, one must approach it first as a unity, and seek to understand it in its unity. Only then will its separate departments—its theory of the State, of Political Economy, of Proletarian Politics—acquire their full meaning. To approach it piecemeal is to court misapprehension at the outset; because by approaching it in this way, one excludes Marxism, ab initio, as an attitude to practical activity, in which theory and practice acquire a new unity, and abstract propositions have meaning only when interpreted concretely. Only in its concrete application to current politics; only as expressed in the activities of the Communist Party, can Marxism be fully understood and learned.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1932/v08n03-sep-1932-New-Masses.pdf