In 1922 the ‘Global South’ was called ‘the East’, or in Marxist terms, the colonial and semi-colonial world. This session of the Comintern’s Fourth Congress sees a report by Holland’s Van Ravenstein, with discussion from M.N. Roy, Sen Katayama, Boudengha Tahar, Karl Radek and delegates from China, Egypt. Australia, Britain on the topic of ‘the East’–China, Japan, the new Turkish republic, and pan-Islamism.

‘The Eastern Question’ from Abridged Report of the Fourth Congress of the Communist International, 1922.

THE EASTERN QUESTION

SESSIONS, 19-20, November 22-23, 1922.

Chairmen: Comrades Kolaroff, Carr.

Speakers: Comrades Van Ravenstein, Van Overstraaten, Roy, Katayama, Tahar Boudengha, Webb, Liu-Yeu-Chin, Hosn-el-Orah, Earsman, Saferot, Nik-bin, Radek.

Ravenstein (Holland): Comrades, our incomparable pioneer and theorist, Rosa Luxemburg, has proved in her greatest and best theoretical work, that the process of the accumulation of capital is impossible without non-capitalist surroundings, which it proceeds to destroy.

The entire colonial policy of capitalism from the 15th to the 20th century is a long series of proofs. The destruction of primitive economy, as well as of all pre-capitalist forms of economy is one. Capitalism is using various ways and means, and the ever-increasing taxation is everywhere one of the most important of these means, as in British India, in the Dutch Indies, in the French North American possessions and in all the new colonial countries. This development has also taken place in the Turkish empire. The well-known radical British writer, Brailsford, in his excellent work of “Macedonia,” came to a Marxian conclusion. He described the struggles of the revolutionary Slav nationalities in Turkey under Abdul Hamid. He says, for instance:

“In so far as European influence succeeded since the Crimean war to press on the Turks an illusory semblance of culture, it has only furthered weakness and disintegration.”

And he adds:

“An even greater influence was perhaps exercised by the so-called capitulations, which created for the subjects of the so-called cultured Powers a State within the State.”

The position of these foreign capitalists does not differ in the least from the privileged condition of the nobility in the old aristocratic monarchies previous to the bourgeois revolution. The nobility was also exempt of all taxation, and among other rights, had also the right to crush the common people underfoot. The only difference is that this modern capitalist aristocracy in Turkey, as well as in the other Eastern countries, consists of elements alien to that country. This state of affairs would have been introduced after the war by the West European capitalism also in Russia, if it had succeeded in crushing the proletarian revolution. In fact, the capitulations are so to speak the crux of the domination of foreign capitalism over the East, which it not only exploits but also debases.

It is self-evident that the new Turkey, which with the support of the peasant masses has won a victory over the hirelings of European capitalism, will demand at the peace negotiations, the abolition of the capitulations, and make the fulfilment of this demand, so to speak, a condition sine qua non.

As long as they are not annulled, the state of abject subjection to European capitalism remains.

But the Turks, who, according to the English statesman, Asquith, had been for ever banned from the European paradise, are now returned. The national rivalries in the Balkans are as bloody and as terrifying as ever. Once again Bulgaria has been overthrown and humiliated, the slave of European capitalism. And when one considers the situation of the other Balkan peoples, one notices only one apparent difference between now and 1913—their position is much worse and far more insecure. Greece has been once more crushed to death by her latest war against the Turks which her bourgeoisie forced upon her.

Comrade Radek has recently given us a description of the contemporary financial and economic situation of that country, which gave us a clear view of its present ailment. One may obtain a clear historical view of the situation by comparing the present condition of Greece with its conditions previous to the Balkan war. In 1890 Greece had borrowed 570 million francs, of which she only received 413 million. Every inhabitant of this small and poverty-stricken land was burdened with a share of this debt amounting to 260 gold francs. This debt necessitated in 1898 a fund of 58 million per year in gold francs, and as the total national income was much lower, bankruptcy appeared to be inevitable.

A new war, that unhappy war, which, in 1897, Greece declared against Turkey, and which burdened the country yet more heavily, gave an opportunity to international finance once more to fasten upon Greece the financial shackles from which she had previously freed herself. An International Financial Commission was formed with full control over the fixing and imposition of taxes which had become necessary for the payment of the national debt, as well as for the payment of war indemnity to Turkey. Thus the Greek people were once more flung into indebtedness. Nowadays, Greece has a shattered economic life, is financially helpless, and is burdened with an atrocious indebtedness and with a population of ragged refugees from Anatolia and Thrace. In fact, the country is now in a state far worse than any in which it found itself since the War of Independence. Such are the results of imperialism and the war for one of the victors of 1912-13.

Turning to Palestine and Mesopotamia, which in name are mandatory countries of the League of Nations, they are in reality under British domination. However, it cannot be said that imperialism, and especially British imperialism, has hitherto derived much satisfaction from these new conquests.

The occupation of Mesopotamia, which was the inevitable consequence of the war, has created for the British Empire a situation against which Brailsford uttered a warning even during the war, in his book, “A League of Nations,” in which he said: “The occupation of Mesopotamia would weaken Great Britain strategically and politically.”

There is every reason to believe that Great Britain is endeavouring to establish at all costs its supremacy on the mighty Arabian Continent. A well-known explorer, Mrs. Rossita Forbes, who is in the service of the British Government, left recently for the Arabian desert, carrying secret instructions. Probably her business will be to drive the Bedouin chiefs into a renewed alliance with Great Britain by means of gold and costly presents. In the Arabian Continent, nothing less than the route with India will be at stake during the next few years for Great Britain. If during the next few years the Arabian tribes and the Arabs in general desired to get rid of the British guardianship, the strategical bridge, which took Great Britain two hundred years to build, would collapse.

Such mighty questions are now at stake in the Near East.

Imperialism cannot endure unless the imperialists retain their political dominion over the Asiatic peoples, unless they can continue to exploit the Mohammedans, the Hindoos, the Chinese and the other nations of the Far East. Why is this? Because the liberation of the Mohammedan and other Oriental peoples will imply the cessation of the tribute they pay to European capitalism, and without this tribute the accumulation of capital cannot continue.

Now an arrest of accumulation is the most deadly wound that can be inflicted on capital. It cuts off the blood supply, as we have been taught once more by the happenings of the last two years.

The movement, the revolution, which is now affecting the whole of the East, both Near and Far, and which will bring complete political independence to these regions, is irresistible.

The Mohammedan peoples aspire towards economic as well as towards political emancipation. That is why the movement among them is such a menace to Western capitalism.

For some decades there has been in progress a powerful movement throughout the Mohammedan world. From time to time it has been so extensive as to bridge material and racial differences. I refer to the Pan-Islamic movement.

Stoddart, one of the most recent historians of Islam, has pointed out how greatly the events of the years immediately preceding the world war increased the sense of solidarity among the Mohammedans and stimulated their hatred for Europeans.

“We must not,” writes Stoddart “allow ourselves to be misled by the fact that the revolts of the Mohammedan peoples of the Near East during the years from 1918 onwards have at first sight a nationalist aspect. Mohammedan Nationalism and Pan-Islamism, however different they may be, are identical in their aspiration towards the complete freeing of Islam from European political control. Islam is capable of constituting a sort of unity as against the capitalist world; for the bond which unites all the Mohammedans is something more than a religious bond. Islam is more than a religion; it is a complete social system; it is a civilisation with its own philosophy, culture and art. In the course of many centuries of struggle with the rival civilisation of Christianity it has become an organic and self-conscious whole.”

This bourgeois student of Islam is at one with the most noted Mohammedan men of learning in his conclusion, “The relationship between Western capitalism and the Eastern world, which for a century has been passing through its age of renaissance (a renaissance which may be said to have begun in Arabia at the opening of the 19th century of our era) the relationship between a capitalist world which is exhausted and undermined by the excess of its labours and the deepness of its wounds, which is profoundly disintegrated and has an enemy within its own household, the revolutionary proletariat, and a Mohammedan world which in every respect, alike religious, cultural, political, and economic is rising out of the abyss of decay into which it has sunk during the eighteenth century—this relationship is once again as greatly strained as it was in the days of the Crusades, when, after the appearance of the Turks in the Moslem world of the eleventh century, one hundred years’ war ensued between East and West.”

In the century of warfare during the middle ages, the West bore off the palm of victory, and gathered strength from the struggle; even though deep and incurable wounds were inflicted on world civilisation.

Now the relationship has been reversed. Decadent Western capitalism is faced by the menace of the young and increasingly vigorous world of the East and of Islam, where countless millions have for decades been debased, misused, and exploited by imperialism, until at length they turn in revolt.

The West is weakened in energy and diminished in greatness. It has a foe within its own household, the revolutionary working class, which would have overthrown the whole structure long ago but for the support given to the tottering edifice by the socialist traitors. Nevertheless, the contrast with the years before the war is notable. Prior to the war Czarism was quite as dangerous as Western imperialism to oriental freedom, to the freedom of the Mohammedan peoples. But Czarism has been destroyed, and proletarian Russia has taken its place; proletarian Russia, the friend of genuine self-determination of the freedom of oriental nations.

The international proletariat, therefore, acclaims the political aspiration of the Mohammedan nations towards complete economic, financial, and political enfranchisement from the influence and dominance of the imperialist States; acclaims it as an aspiration which, even though it may not aim at the abolition of wage slavery and at private ownership of the means of production in Mohammedan lands, none the less menaces the foundations of European capitalism.

Roy (India): Comrades, at the Second Congress of the Communist International the general principles concerning the struggle for national liberation in the colonial and semi-colonial countries were laid down. The general principles were formulated by which the relations of the proletarian revolution and the proletarian movement of the industrially and economically advanced countries to the national struggle of the backward peoples, should be determined and the experience that we had in 1920, that is, at the time of the Second Congress of the Communist International, did not permit us to develop those principles to any great extent. But since those days, during the last two years, the movement in the colonial and semi-colonial countries has gone through a long period of development, and in spite of all that has been left undone, and in spite of all that ought to have been done by the Communist International, and particularly by the Communist Parties of the Western countries, to establish closer relations with these movement, and to develop them, we are, to-day, in a position to speak with more knowledge and more experience and understanding of these movements in the colonial and semicolonial countries.

The task before us to-day in this Fourth Congress is to elaborate those fundamental principles that were laid down by the Second Congress of the Communist International.

With this in view all the Eastern delegations present at this Congress in co-operation with the Eastern section of the Communist International have prepared a thesis which has been submitted to the Congress. In this thesis the general situation in the East has been laid down and the development in the movement since the Second Congress has been pointed out and the general line which should determine the development of the movement in those countries has also been formulated.

At the time of the Second Congress, that is, on the morrow of the Great Imperialist War, we found a general upheaval of the colonial people. This upheaval was brought about by the intensified economic exploitation during the war.

This great revolutionary upheaval attracted the attention of the whole world. We had a revolt in Egypt in 1919, and one of the Korean people in the same year. In the countries lying between these two extreme points there was to be noticed a revolutionary upheaval of more or less intensity and extensiveness. But at that time these movements were nothing but big spontaneous upheavals, and since those days the various elements and social factors which went to their composition have clarified, in so far as the social economic basis has gone on developing. Consequently we find to-day that the elements which were active participants in those movements two years ago are gradually leaving them if they have not already left them. For example, in the countries which are more developed capitalistically, the upper level of the bourgeoisie, that is, that part of the bourgeoisie which has already what may be called a stake in the country, which has a large amount of capital invested, and which has built up an industry, is finding that to-day it is more convenient for its development to have imperialist protection. Because, when the great social upheaval that took place at the end of the war developed in its revolutionary sweep it was not only the foreign imperialist, but the native bourgeoisie as well, who were terrified by its possibilities. The bourgeoisie in none of those countries is developed enough as yet to have the confidence of being able to take the place of foreign imperialism and to preserve law and order after the overthrow of imperialism. They are now really afraid that in case foreign rule is overthrown a period of anarchy, chaos and disturbance, of civil war will follow that will not be conducive to the promotion of their own interests.

This, naturally, has weakened the movement in some of the countries, but at the same time this temporary compromise does not fundamentally weaken the movement. In order to maintain its hold in those countries, imperialism must look for some local help, must have some social basis, must have the support of one or other of the classes of native society.

The temporary compromise between native and imperial bourgeoisie cannot be everlasting. In this compromise we can find the development of a future conflict.

So, the nationalist struggle in the colonies, the revolutionary movement for national development in the colonies, cannot be based purely and simply on a movement inspired by bourgeois ideology and led by the bourgeoisie.

This position brings us face to face with a problem as to whether there is a possibility of another social factor going into this struggle and wresting the leadership from the hands of those who are leading the struggle so far.

We find in these countries where capitalism is sufficiently developed that such a social factor is already coming into existence. We find in these countries the creation of a proletarian class, and the penetration of capitalism has undermined the peasantry and is bringing into existence a vast mass of poor and landless agrarian toilers. This mass is being gradually drawn into the struggle, which is no longer purely economic but assumes every day a more and more political character. So also in the countries where feudalism and the feudal military clique are still holding leadership, we find the development and growth of an agrarian movement. In every conflict, in every struggle, we find that the interests of imperial capital are identical with the native landowning and feudal class, and that, therefore, when the masses of the people rise, when the national movement assumes revolutionary proportions, it threatens not only the imperial capital and foreign overlordship, but it finds also the native upper class allied with foreign exploiters.

Hence we see in the colonial countries a triangular fight developing, a fight which is directed at the same time against foreign imperialism and the native upper class, which directly or indirectly strengthens and gives support to foreign imperialism.

And this is the fundamental issue of the thing that we have to find out—how the native bourgeoisie and the native upper class, whose interests conflict with imperialism or whose economic development is obstructed by imperial domination, can be encouraged and helped to undertake a fight? We have to find out how the objective revolutionary significance of these factors can be utilised. At the same time we must keep it definitely in mind that these factors can operate only so far and no further. We must know that they will go to a certain extent and then try to stop the revolution. We have already seen this in practical experience in almost all the countries. A review of the movement in all Eastern countries in the last few years would have helped us to develop our point, but the time at our disposal will not permit that. However, I believe most of you are fairly well acquainted with the development of the movement in those countries. You know how the movement in Egypt and India had been brought to a standstill by the timidity, the hesitation of the bourgeoisie, how a great revolutionary movement which involved the wide masses of the peasantry and the working class and which constituted a serious menace to imperialism, could not produce any very serious damage to imperialism simply because the leadership of this movement was in the hands of the bourgeoisie.

Hence it is proved that although the bourgeoisie and the feudal military clique in one or other of these countries can assume the leadership of the nationalist revolutionary struggle, there comes a time when these people are bound to betray the movement and become a counter-revolutionary force. Unless we are prepared to train politically the other social element, which is objectively more revolutionary, to step into their places and assume the leadership, the ultimate victory of the nationalist struggle becomes problematical for the time being. Although two years ago we did not think of this problem so clearly, this tendency remained there as an objective tendency, and to-day, as a result of that, we have in almost all Eastern countries communist parties, political parties of the masses. We know that these communist parties in most of these countries cannot be called communist parties in the Western sense, but their existence proves that social factors are there, demanding political parties, not bourgeois political parties, but political parties which will express and reflect the demands, interests, aspirations of the masses of the people, peasants and workers, as against that kind of nationalism which merely stands for the economic development and the political aggrandizement of the native bourgeoisie.

We have to develop our parties in these countries in order to take the lead in the organisation of its United Front against Imperialism. Just as the tactics of united proletarian front leads to the accumulation of organisational strength in the Western countries and unmasks and discloses the treachery and compromising tactics of the Social-Democratic Party by bringing them into active conflict, so will the campaign of united anti-imperialist front in the colonial countries liberate the leadership of the movement from the timid and hesitating bourgeoisie and bring the masses more actively in the forefront, through the most revolutionary social elements, which constitute the basis of the movement, thereby securing the final victory.

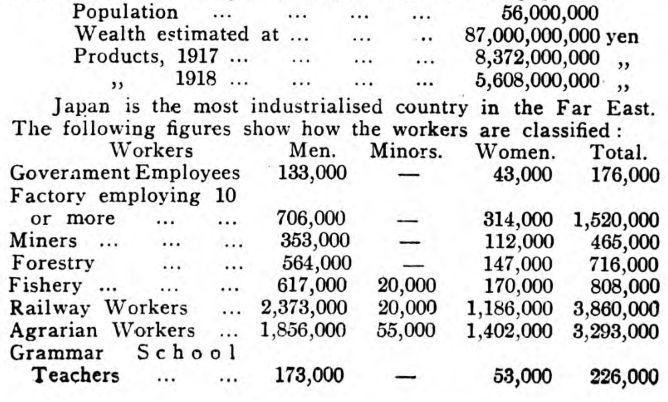

Katayama (Japan): Comrades, I rise to present the Japanese case and also the case of the Far East. Japan occupies a very important place in the coming socialist revolution. Japan is important in the revolutionary movement of the world because in the near future the workers of Japan may rise against the capitalists. This is the reason why I want your serious attention. We all know, and I do not need to tell you, that we must protect the Russian revolution. Soviet Russia is menaced by Japanese Imperialism, and for this reason alone the Fourth Congress and the Communists of the world should pay more attention to this subject than it has done hitherto. During the Congress Japan is represented here in order to make progress in the social revolution of the world. This is the reason I want to read what I presented in my report on Japan and Japanese conditions. I want to give you a few facts. They are facts which will give you some idea of what Japan is:

These are wage workers, exploited in some cases very much. The work-day in the spinning factory consists of 11 and 12 hours and there are also night shifts. Women and young girls work these hours in the factory. Besides this there are 4,160,000 families of poor peasantry and combined tenantry.

In 1920 there were 838 unions, with a membership of 269,000, and in 1921 671 unions, with a membership of 246,000, and 229 tenant unions, with a membership of 24,000. There has, of course, been an increase since that time. The landowners’ union which is really a peasant proprietors’ union, has a membership of 1,422,000. There are also mutual aid associations. In 1920 there were 685, with a membership of 2,000,000. These unions aided 3,169,000 persons, with money amounting to 1,551,000 yens.

Comrades, these are bare facts based upon a government report. Of course, as to the labour unions, the government has tried to minimise their number; we have more. The Japanese workers are organised and exploited by the militarist government. They are suppressed whenever they start a liberal movement, but they are awakening.

Our union leaders understand the capitalist conditions and are showing the workers that the capitalist system cannot remedy the unemployment problem.

I want to say a word now about the women’s movement, because it has been somewhat neglected at this Fourth Congress. Japanese women workers are very much exploited. They are prisoners in the companies’ dormitories and they work. twelve hours, both in day shifts and night shifts. Formerly, Japanese women were prohibited from attending political meetings and forming political associations. But these restrictions have now been abolished. Japanese women are being educated in the highest educational institutions in the country, and they are utilising their education for the improvement of their position. They are not only taking part in the political life of the nation, but many have already joined trade unions. There are several thousand women members in the Japanese Federation of Labour. When a strike occurs the women are very active.

The Japanese imperialism has become very unpopular amongst the Japanese workers, but is still very strong. I will give you an instance. Formerly, when a Japanese mother wanted to frighten her child she would say that she would put him to prison, but to-day she threatens that she will make a soldier of him. The imperialists are preparing for the next war. Therefore, we in conjunction with the Chinese Delegation propose that this Fourth Congress of the Communist International should pass a resolution against the occupation by Japan of Northern Saghalin, and encourage the Japanese revolutionary workers to fight against imperialism, and to prepare for the coming revolution in Japan.

Tahar, Boudengham (Tunisia and the French colonies): Comrades, I do not think that it is necessary to read to you my report, as each of the various language groups have received a copy; I will therefore limit myself to elaborating certain points.

French imperialism has colonies not far distant from the Homeland, which enables it easily to recruit its forces either for future wars or for stifling the proletarian revolution in France.

At the same time there is an insurgent in North Africa. The communist nucleus, which was formed in Tunisia after the Conference, has taken advantage of this movement. Owing to the seriousness of the situation which may arise in the event of a proletarian revolution, it is doing its utmost to prevent French capitalism from getting the native population of North Africa entirely into its power. In order to accomplish this task, we have approached the workers and peasants, either through our Arabian dailies or through public meetings. We were so successful that the government became alarmed and made domiciliary visits and arrests. It even proclaimed our Party illegal, which forced us to carry on underground work. I must admit that this act of the government as well as the suspension of our Arabian papers has done us great harm, for our activities were not limited to Tunisia, but extended throughout the whole of North Africa.

Here I must complain of the French Communist Party, both for its lack of assistance and the character of its press articles dealing with our struggles.

I trust that the French Comrades, regardless of any tendencies, will set to work immediately after the World Congress, in order to initiate a policy of communist action in the colonies by the establishment of a central organ and the collaboration of colonial Comrades in the Managing Committee.

The French Comrades must understand once and for all that a proletarian revolution in France is bound to fail as long as the French bourgeoisie will have at its disposal the colonial population. Likewise, the liberation of the latter will only be possible when there will be in France a Party of revolutionary action and not an opportunist Party.

The Communist International must also take the matter in hand by attaching to itself a permanent representative of the French colonies.

I am also of the opinion that the British party has not done everything which should have been done. What has the British party done in order to support the revolutionary movement in India and in Egypt? The Communists must not limit their actions to their home territory while ignoring the thousands of people who are oppressed by their bourgeoisie and groan under the yoke of their own imperialists. I am of the opinion that to abandon peoples whose liberation and future depend on a communist party, as is the case for the British party, is nothing but cowardice.

On the other hand, Comrade Malaka was not quite sure the other day if he should support Pan-Islamism. You must not be as diffident as all that. Pan-Islamism at the present juncture is nothing but a union of all the Mussulmans against their oppressors. Thus, there is no doubt whatever that they must be supported.

On the other hand, questions of a religious nature came to oppose the development of communism. In Tunis, we had the same difficulties as you in Java. Every time people came forward to discuss with us the non-assimilation of communism with Islamism, we invited these mischievous people to meet us in public debate. We proved to them that the Mussulman religion prohibits the exploitation of labour, this being the principal basis of this religion. Secondly, we told them that if they are so religious, they must begin by applying the religious principles and paying one-tenth of their fortunes, including capital and interest, for the benefit of those who are not able to work. I can assure you that every time they debated with us by bringing forward their religious principles, they came off second best.

I think that Comrade Malaka’s fears are unfounded. The progress of our ideas among the Mussulmans has exceeded all expectations. We have received from all parts of the Mussulman world, especially when we still had our Arabic papers, numerous letters of congratulation for our methods of applying communism in Mussulman countries.

I trust that the Congress will accept the conclusions of my report, which are necessary if the communist idea is to triumph among the oppressed peoples.

I conclude my statement by greeting the Congress of the International. (Applause.)

Webb (England): Comrades, at the risk of again incurring criticism from Comrade Radek because of my reference to the 21 points on this important question—the oriental question—it is my intention to refer to them again and especially No. 8, as presented by the Second Congress of the Communist International.

It reads as follows:

“In the colonial question and that of the oppressed nationalities, there is necessary an especially distinct and clear line of conduct of the parties of countries where the bourgeoisie possess such colonies or oppress other nationalities. Every party desirous of belonging to the Third International should be bound to denounce without any reserve all the methods of ‘its own’ imperialists in the colonies, supporting not in words only but practically a movement of liberation in the colonies. It should demand the expulsion of its own imperialists from such colonies and cultivate among the workmen of its own country a truly fraternal attitude towards the working population of the colonies and oppressed nationalities, and carry on a systematic agitation in its own arm against every kind of oppression of the colonial populations.”

Such was the decision of the Second Congress of the Communist international. Since those days we have had the development of the revolutionary nationalist movements in Egypt, in Persia, in Mesopotamia, in India and in Turkey. Yet it is safe to say that even the most mature Communist Parties, not these small parties or these revolutionary groups which are in the process of becoming Communist Parties, but the most developed Communist Parties affiliated with the Third International have not fulfilled these obligations to the revolutionary nationalist movement in the ways enumerated.

It is true that a criticism has been levelled at the Party which I represent with regard to its attitude to the national and colonial question. It is within the framework of the British Empire that you have the liberation, movements of Ireland, Egypt, and of other parts of Africa apart from Egypt, and India as well as the colonies making up the British Empire. But our sins of omission can in the main be attributed to the fact that our party is only a very small party and a very young party which has been faced with numerous internal difficulties which it was necessary to overcome before we could pay the necessary attention to the colonial problem.

Comrade Trotsky, in the book he wrote prior to the Russian Revolution, criticised the strongest section of the Second International, the German Social Democratic Party, and pointed out that the Social Democracy had developed into socialist imperialism.

I will stress the note this morning that we must do everything to prevent those elements coming into the Communist International which would endeavour to make the Communist International an International for Communist Imperialism equivalent to the Socialist Imperialism which characterised the social democracy.

In a recent number of the “Fortnightly Review,” there was a very significant article. In this article entitled “Kemel, the Man and the Movement,” the Review says: “There can be no doubt that while the Kemalists are sincerely pursuing nationalist aims, the Bolsheviks are taking advantage of Turkish national aspirations in order that Western civilisation might be attacked at its weakest point, and that amid fresh commotions revolutionary activity might be renewed in an exhausted Europe.” It concludes by saying that England and the Allies may hand over Constantinople to the Turkish nationalist Kemal Pasha, but before doing so they must prove to the world that Kemal Pasha is no longer a pawn in the hands of Soviet Russia. A statement of that description from an authoritative capitalist periodical like the “Fortnightly Review” proves that the bourgeoisie are awake to the dangers of the transformation of a revolutionary nationalist movement into a revolutionary proletarian movement directed against the bourgeoisie. Therefore, these points in the theses spoken to by Comrade Roy in reference to the need for helping the proletarian elements in these countries themselves, but also by those Communist Parties that belong to these countries that are oppressing the countries in which these movements are operating at the present time.

Lin-Yen-Chin (China): Comrades, owing to the limit of time I have at my disposal, I can only give you: a general idea of the present situation in China.

First, I must speak of the political situation. From May of June of this year we have witnessed the downfall of two governments in China.

First was the downfall of the Southern Government, that is, the revolutionary government headed by Sun Yet Sen. This government was overthrown by a subordinate military member of the government, a member of the Nationalist Party. The downfall came owing to the differences of opinion between the leader, Sun Yet Sen, and this subordinate member concerning the plan of military expedition against the North. This signifies the complete failure of the military plan of revolution. The Kuomintang Party, the nationalist revolutionary party in China, entertained for years a scheme of making military revolution. That means that by military conquest of the provinces they could realise a democracy in China. They did not carry on mass propaganda in the country. They did not organise the masses. They only strove to utilise military forces to achieve their aim. Before they had conquered Kwantung in 1920, they established a government, and they wanted to exhaust all the resources of the Kwantung province to raise an expedition against the Northern Government which is the government of the feudal militarists and the agent of world imperialism.

Civil war was waged during April and May in the North between two factions of the feudal militarists. One faction of the militarists was pro-Japanese, the other pro-American. This ended in the victory of the pro-American group.

The Chinese Northern government was dominated for about five years by the Japanese imperialism. This imperialism maintained its influence by lending money to the Northern Government to strengthen it in the civil war. The Japanese Government bribed officials to secure rights and interests in the Chinese mines, the right to construction of railways in Shantung, etc. Hence the Chinese population maintained a hostile attitude towards Japanese imperialism and the pro-Japanese agents in the Northern government. Owing to their deep hatred of the Japanese imperialism in China, they tended to be more and more in favour of giving support to the American imperialism. Owing to the fact, also, that the Northern government is more reactionary and this government is headed by Clan-so-Lin, the people are more and more sympathetic to the militarist group—the Wu-pei-fu group, the more progressive one which advocates the reduction of the army and the abolition of the tuchunate, i.e., the feudal division of the provinces, and who have the support of the Americans.

Second, I must mention the labour movement. This movement in China this year progressed very rapidly. At the beginning of this year we witnessed the Hongkong seamen’s strike,’ which lasted more than fifty days, which was first limited to economic demands and soon became a nationalist factor against British imperialism. This strike was at first only limited to the seamen, but it became a general strike against British imperialism in the Hongkong colony, involving a spread to the North. There was the Peking-Mukden railway strike, and the trouble then spread to the centre of China. There was a strike in the iron and steel works in Hongkong, of the textile and tobacco industries in Shanghai, and another in the mines. All these strikes succeeded each other very rapidly. The spread of revolt against the capitalist class indicates the awakening of the labouring masses. This shows that the mass movement in China is not a dream of the Socialists, but that it has already come into being. It also shows that the Communist Party can be successful in agitating among the masses. It shows that the Communist Party in China will progress favourably, unlike in the previous years, when it was merely a study circle, a sect. This year we can witness our Communist Party developing within the masses.

Hosni el-Orabi, speaking in Arabic, said: The Egyptian worker suffers under the capitulations; he suffers under the yoke of British imperialism, foreign companies, and his own bourgeoisie.

Egypt is now ripe for the advent of Socialist ideas. One proof which I can give you is the growth of the Egyptian Socialist Party. The Party was legally established in August of this year, and during the few months of its existence has attracted 1,000 members to its ranks. In view of the ripeness of Egypt for the reception of Socialist ideas, we are anxious that no obstacle shall be placed in the way of a steady inflow of Communist propaganda and a development along Communist lines. We feel that if Egypt is left out of. the brotherhood of the Communist International and her present eagerness allowed to run to waste, her backwardness may interfere with the development of the revolution in the East and may greatly retard the advent of the revolution in the West.

The marvellous uprising of 1919 and 1920 shook the power of British imperialism and taught the Egyptian capitalists a salutary lesson. Alarmed by these events, the British Government, in collaboration with the Egyptian capitalists, grandiloquently granted the complete independence of Egypt. But the people were not deceived by these hollow promises. What did they amount to? First, the protection of communications; this was conceded because Great Britain wished to safeguard her passage to India. Secondly, a co-government of the Soudan; this was to provide England with another source of raw cotton to feed the Manchester cotton mills. Thirdly, the protection of the minority populations. Fourthly, abolition of the capitulations.

The last two claims were advanced in order to give Great Britain a legal right to interfere in Egyptian affairs.

The Egyptian capitalists now formed a Liberal Party, whose object was to protect the new constitution and to ratify the treaty between Egypt and Great Britain. In order to do this, they had to draw up a programme and to select candidates to represent this opinion in a parliament—the elections to which are likely to take place in January next.

We intend to utilise the coming elections to the first Egyptian parliament. In the weeks that must still elapse before the events, we are going to prepare the soil in the hope of seeing some of the Comrades elected to represent the workers in the new body. If we are successful in winning one or two seats it will give an added prestige to Communism in the East and will consolidate the basis of our Party in Egypt.

Earsman (Australia): There are two points in the theses which have been drawn up and submitted to the Congress on which I wish to speak.

The first is the developing of the revolutionary movement in the colonial countries, particularly those oppressed in the Near and Far East.

The second point, the one we are particularly interested in, is the problem arising from the conflict which is developing in the Pacific. The most outstanding difficulty that we have to overcome is the prejudice arising amongst the white workers from the fear of cheap coloured labour. We find that in the countries most concerned, Australia, America and Canada, they have laws prohibiting the immigration of coloured labour into those countries, the workers believing that the importation of this labour is to be used against them for the breaking down of the conditions and the standards of living which have been set up in those countries.

Those of you who have given any attention to the Pacific must realise the danger of another world war in the Pacific. And if you realise that you will come to this conclusion: that the “fear of a Yellow invasion,” would be sufficient to gather behind it numbers unequalled in the past. Because of that, it is our particular mission at the present time and in the next few months to have these slogans broken down, to get the workers to fully realise them and understand what they mean.

In the theses is made a proposition which we believe will be most successful in combating the work of the capitalists in those countries, and the Trade Union Congress in Melbourne this year passed a resolution deciding that the best method of bringing about a solid understanding between the workers of the North and South Pacific would be by the calling of a Pan-Pacific Congress. Such a Congress would bring the workers of Japan, China, Malay, India, America, Canada, Australia and New Zealand together, and then they would be able to thrash out the problems that they are faced with and arrive at understandings which would be the means of getting the workers to realise how reactionary their past ambitions had been as far as coloured labour is concerned.

In making that proposal in the theses we hope and trust that every assistance will be given to the workers in these countries will be held and a definite programme worked out in a practical fashion.

Our first duty is to unite all the national. revolutionary movements in the colonies into a united anti-imperialist front. In these backward countries the elements furthering the petty bourgeois development have not yet sufficiently separated themselves from the feudal elements, and these feudal elements are partisans of foreign imperialism. The struggle against the agrarian feudal regime is necessary. In Persia this struggle is taking place conjointly with the struggle against imperialism.

At the time of the Second Congress we had no Communist Parties in those countries.

The Second Congress of the Comintern declared that we must support the independent working class movement in the most backward countries in all its forms. We have followed this policy. The small Communist Parties have already become a political force. They are capable of organising the revolutionary nationalist movement and of pushing it forward.

We must organise the working class of these backward countries because the proletariat of the colonial and semicolonial peoples is of vital importance for the victory of the proletarian world revolution. (Applause.)

Okhran: Comrades, the Third International has recognised the liberation movement of the colonial peoples as being of capital importance to the world revolution. It is quite inexplicable, therefore, why the Communist Parties of the West have not till now devoted to the Eastern and colonial questions as much attention as they should.

As startling proof of this, we greatly regret to say that the British Communist Party has not as yet inserted in its programme of action the special plank concerning the work of Communist Parties in the colonies.

In order that the masses may be led to understand the significance of the anti-imperialistic United Front, the situation must be visualised and made concrete by inserting the practical demands of the masses, such as agrarian reform, administrative and taxation reforms, parliamentary reform, etc.

Taking into consideration the fact that the Second and Two-and-a-Half Internationals, now see themselves obliged to take a stand against imperialism in the West and the East, the anti-imperialistic front must be proposed to the opportunist European parties on the basis of the independence of the Oriental and colonial countries.

It should then be proposed to the British Labour Party that it exert pressure upon its government in order to (1) compel the Lausanne Conference to formulate peace terms in conformity with the National Pact; (2) immediate evacuation of Constantinople and all of Thrace; (3) the settlement of the question of the Straits in conformity with the Russo-Turkish Treaty and with the participation of all states bordering on the Black Sea; (4) to publish articles on this question in working class periodicals; (5) the evacuation of Syria, Mesopotamia and Palestine, and the recognition of the nationalist independence of all colonies and semi-colonies.

The Communist Parties of those countries which possess colonies and semi-colonies, and particularly those of France and Great Britain, should support every revolutionary movement for independence, and should aid by every possible means the Communist Parties of those countries and should endeavour to assure their legalisation.

The following are the essential tasks of the young Communist Parties of the Eastern countries:

(1) To support the movement for national emancipation by all means, and unite all forces in an anti-imperialistic United Front. To exert the most careful vigilance so that the movement for national freedom be not sabotaged by the ruling class.

(2) To demand democratic reforms for the broad working masses. These tactics will bring to the Party the sympathy of all labouring classes, and will transform the Communist Party into a mass party of the people.

Nik-bin (Persia): Comrades, Persia is at present in the transition stage from the patriarchal order to capitalism. In Persia there is dual power. The Communist Parties there have not only to struggle against their own feudal lords, but also against the imperialists, especially with the British who have allied themselves with the Persian feudal lords and who are impeding Persia’s transition to the capitalist order. The world economic crisis was reflected in Persia in the sense that the Persian market was to a certain extent neglected by the capitalists. This led to the development of the native home industries, and with it to the awakening of the working class. For this and various other reasons, the Communist Party came into being in Persia. At present, this organisation has 1,000 members throughout Persia. There are also trade unions with a membership of 15,000 throughout Persia, Teheran, the capital, claiming 12,000 of it. The Persian Communist Party has the following policy. From a strictly party point of view, it would be wrong to organise in Persia a wide Communist Party. The organisation there has a strong nucleus, mostly consisting of workers. On the other hand, there are in Persia organisations on the model of trade unions and also trade unions which are entirely under the influence of the Communist Party. The Party directs the policy and has a great influence on trade union activities.

The Persian Communist Party has proved to be stronger even than the bourgeois parties. The bourgeois parties, as represented by the so-called social-democrats, who have a democratic programme, are themselves seeking to form a bloc with us. It is safe to say that in the very near future the Persian Communist Party will be very successful.

Radek (Russia): Comrades, our way of dealing with the movement in the East, since the Second Congress, should now be subjected to the test. You will recollect how at the Second Congress of the Comintern we discussed the Theses on the great revolutionary importance of the movement in the East and on the necessity for the Comintern to support that movement. Our attitude at that time caused a clamour not only in the world of capitalism, but also in the parties of the Two and Two-and-a-Half Internationals While the entire Two and Two-and-a-Half Internationals are helpless against capitalism, the struggle in Turkey has upset the equilibrium of the whole of Western Europe. This is the answer to the question whether the movements in the East are of revolutionary importance in the fight for the overthrow of capitalism or are merely the political game of Soviet Russia and the Communist International.

Now there is an important point raised by our Turkish Comrade. Our theses stated that the exploited East must and will fight against international capitalism, and that for this reason we ought to assist it. Now, we find at the head of the oriental national movements neither Communists nor even bourgeois revolutionaries, but for the most part representatives of the decayed feudal cliques belonging to the military and bureaucratic classes. This fact brings our aid to the Eastern peoples into contradiction with the question of our attitude towards the ruling elements. The question was brought to a head by the persecution of Communists in Turkey and by the military suppression of Chinese strikers by Wu Pei-Fu troops. As Communists, we may clearly and frankly state our attitude upon such matters without resorting to diplomacy. In promising our aid to the awakening East, we did not for a moment lose sight of the class struggles that will yet have to be fought out in the East.

The persecution of Communists in Turkey is part of the class struggle which is only beginning to develop in Turkey. There is bound to be a struggle not only between the working class and the young bourgeoisie, but also within the camp of the ruling clique. It is no secret that the Minister of the Interior, Rauf Bey, and Refar Pasha are primarily responsible for the Communist prosecutions, and that they were the ones who favoured compromise with the Entente and opposed the dethronement of the Sultan. We tell the Turkish Communists: “Let not the present moment obscure your outlook on the near future!” The defence of the independence of Turkey, which is of paramount international revolutionary importance, has not yet been achieved. You should defend yourself against the persecutors, you should deal blow for blow, but you should also realise that the fight for freedom is not yet over, that you have a long road before you which you will have to follow together with the other revolutionary elements of Turkey for some time to come.

Let us now turn to the situation in China. Comrades, recall to your minds the march of events. When Wu-Pei-Fu defeated Chang-So-Lin he gained possession of the Yang-Tse arsenal, but he failed to gain possession of the railways in the North, which were in the hands of Japanese hirelings. What did he do? He asked the Young Communist Party of China for support, and it gave him commissaries who kept the railways clear for his troops during the revolutionary fight. Everyone who fights against Japanese imperialism in China fights for the revolutionary development of the country. This was understood by the Communists, and they kept the working class alive to the realisation of the importance of the fight for independence. Later on the workers presented their demands to Wu-Pei-Fu, and partly won them. Our comrades in Northern China have won their influence over the historic mission, which was as yet bound up with the mission of the revolutionary bourgeois forces. When the Second and Two-and-a-Half Internationals continually chide us with our undue confidence in the Enver Pashas and. Wu-Pei-Fus, our answer is: “Gentlemen of the Second and Two-and-a-Half Internationals, as there is a petit-bourgeoisie of which you are a part, it will be vacillating between capital and labour, and you who call yourselves socialists and have already a thousand times betrayed the working class, and yet after every betrayal we still come to you and try to win you for the United Front, which you oppose. It is the irony of history that you are being whipped to advance whether you like it or not, although you have betrayed us in the past, you will have to come along with us once more and serve our cause.

We, therefore, say not only from the standpoint of Soviet Russia, but also of the Communist International: You need have no anxiety. We do not stake on the ephemeral policy of this or that clique, but on the great historical stream which is bound to bring together the toiling masses of Western Europe with the awakening peoples of the East in the fight against world capitalism.

Comrades, I will now say a few words anent the reports we heard here about the conditions of our parties and their activities in the East.

I will start with my usual warning: Comrades, do not indulge in too rosy expectations, do not over estimate your strength. When our Chinese comrade told us here: “We have struck deep roots in China,” I must tell him: “Esteemed comrade, it is a good thing to feel confident of one’s strength when one starts to work.” Nevertheless, things have to be seen as they are. Our Chinese party has developed in two parts of China in relative independence from one another. The comrades working at Canton and Shanghai have failed to associate themselves with the working masses. For a whole year we have been arguing with them, because many of them said: How can a good communist waste his time on such trivial things as strikes. Many of our comrades out there locked themselves up in their studies and studied Marx and Lenin as they had once studied Confucius.

In the first instance, it is the duty of the Chinese comrades to take into consideration all the possibilities of the Chinese movement. You must understand, comrades, that neither the question of Socialism, nor of the Soviet Republic are now on the order of the day. Outside of our ultimate aim, for which you must stand up with all the fervour of your communist faith, the immediate task is the uniting of the forces which are beginning to come to the fore within the working class, for two special aims:

(1) To organise the young working class, and

(2) To regulate its relations with the revolutionary bourgeois elements, in order to organise the struggle against European and Asiatic Imperialism.

We are only beginning to understand these tasks. Therefore, we must recognise the necessity of adopting a practical programme of action, by means of which we shall gain in strength. The Communist International orders the Western communist parties to go into the masses, and the first thing we must tell you is: Get out of the Confucian study room of communism, and go to the masses and coolies, and also to the peasant masses, which are in a state of ferment, caused by present day events.

Now as to Japan and India. In both these countries the grouping of the forces is very similar. In Japan, as well as in India, there is already a strong working class. In both countries there is a great social crisis, and struggles for power between the various sections of the bourgeoisie and of the nobility, and, nevertheless, we have not yet a communist movement in these countries. This is a fact. You have only to study the manifestoes which Comrade Katayama published recently in the “Communist International” about the situation in Japan. They are very interesting, for you will find in these manifestoes, which were legally published by various groups of workers, a whole rainbow of shades, from Tolstoyanism through syndicalism and communism to the simplest social reform. And I must admit that in this concert of voices, the voice of communism is still the weakest.

Why? Hitherto we did not know how to take advantage of the mood of the workers (who were going through similar experiences as the British Chartists) in order to prepare them for the tasks with which they are now faced. These tasks consist in the organisation of the working class as a power which could intervene in the class struggle in Japan, in order to establish, first of all, a democracy. I am of the opinion that the development in Japan will not be a mere repetition of the development of Great Britain.

A hundred years have passed, and it is self-evident that the tempo of the development in Japan will be more rapid. History is being concentrated, and even in this bourgeois revolution, now brewing in Japan, we shall probably have soviets established, not as organs of power, but as organs which will unite the working class. But now we must establish trade unions, and a Communist Party, and adopt a program clearly defining the immediate tasks of the working class. The immediate task before us is—to lead the working class into the struggle as an organised body.

In India we have already an ideological centre; I must say that Comrade Roy has succeeded in achieving a big piece of work during the last year in the Marxist interpretation of Indian conditions given in his admirable book, and also in his organ. In no other Eastern communist party has this kind of work been done. It certainly deserves to be supported by the Communist International. However, it must be admitted that as yet we have not done much in connection with the great trade union movement in India and the large number of strikes which convulsed the country. We have not yet understood to make use of the rights which our British overlords are compelled to concede to us. The reception accorded there to Comrade Roy shows that there are some legal opportunities there. But we have not even taken the first steps as a practical workers’ party. And all this means that: “It is a long way to Tipperary.”

Comrades, I trust that we will succeed at this Congress to put the work which our Eastern section has done, with your assistance, on a practical basis, and that we will then be able at the next Congress to put before you practical organisational achievements. When this will have been achieved, the International will not only recognise the great importance of the Eastern question, but will also have the conviction that you are doing the work which is commensurate with the enormous significance of this question.