The veteran Chinese Communist, poet, and schoolmate of Mao with an extensive look at the explosion of revolutionary writers, magazines, and societies that accompanied the larger Chinese revolution of the period–and suffering the similar fates. While many of the works mentioned, unfortunately, remain untranslated, some have been including in International Literature itself.

‘Chinese Revolutionary Literature: A Survey of the Last Fifteen Years’ by Emi Siao (Xiao San) from International Literature. No. 5. 1934.

Up to now there has been a Chinese wall between Chinese and international literature. Chinese literature is still “Chinese” to many readers, notwithstanding the fact that the Soviet revolution in China has become an important factor in the world revolution. An acquaintance with Chinese revolutionary literature will aid in understanding life in China today, the China of wars, intervention and revolution.

Some historical dates: The last twenty years or so in China have been full of important events: the revolution of 1911; the movement of May 4, 1919; the movement of May 30, 1925; the great Chinese Revolution of 1925-27, its subjugation and the new rise of the revolutionary movement. Finally, the establishing of the Chinese Soviet Republic and the frequent victories of the Chinese Red Army. And now we have in China, the revolution, war and intervention.

All this is, of course, reflected on the literary front. In order to throw some light on the literary situation in China today, it is necessary to make a short survey of the historical stages of the development of Chinese literature.

During two thousand years, from the Ts’in and Hwang dynasty feudal literature in the main did not change. Confucianism dominated it. At the beginning of the 20th century, however, the incursion of foreign capital broke this tradition, putting forward the slogan of enriching the country and strengthening the army. The first representative of bourgeois ideology of that time was Liang-Chi-chao. Bourgeois novels begin to appear alongside the feudal novels of Shou-Hu (River Pirates, Travels in the West, Dream in the Red Pavilion, etc.).

The most vivid expression of the national bourgeoisie on the literary front is the movement of the 4th of May, 1919.

May 4

Feudal ideology became a hindrance now to the development of the Chinese bourgeoisie. A struggle grew at first against the old literary language “Weng-Yang” which only a small group of the upper intelligentsia had mastered, for a more nearly colloquial language—”Bai-Hua.” This movement gradually grew into a struggle against feudal ideology, against old Confucianism. Then, under the influence of the October Revolution and the Leninist views on the national and colonial questions this developed into an active political struggle and took the form of the Peking student demonstration of May 4, 1919. Later, when the proletariat raised its head and rapidly moved forward, the 4th of May went down to its historical grave.

The magazine Sin-Tsin-Niang (New Youth) put forward the slogan “against feudal, aristocratic literature, for a popular, realistic and social literature.” The slogan was, however, purely a formal one. No program for the creation of a new literature existed, while the term “popular” should really be read “bourgeois”—many slogans like, for instance, “for Bai-hua,” the employment of old historical names and book themes, etc. were only put out formally. While verbally demanding realistic literature Professor Hu-Shi, one of the main fighters for “Bai-hua” frequently. wrote: “My heart writes with my lips,” a metaphor typical of feudal romanticism. Arguing with all their strength for “pure by objective” analyses of social phenomena, i.e., for naturalism, the adherents of Hu-Shi never defined. this naturalism clearly. This indecision was not accidental. While the French romanticism of the thirties of the past century was a militant, optimistic trend, because the French bourgeoisie was at a progressive stage of development, the new Chinese bourgeoisie was itself contradictory, vacillating, compromising, torn by contradictions. In literature this was expressed by a vacillation between naturalism and romanticism. The immature Chinese bourgeoisie found itself facing resisting feudalism, the attacks of international imperialism, the growing movement of the international proletariat, a rift in world capitalism and the threat from the giant—the Chinese proletariat.

What literary, work did the period of the 4th of May produce? One must admit the literature of this period was very poor indeed. However, since the 4th of May there is a continuous growth of bourgeois literature, although there isn’t a particle of optimism or firmness in it, only sadness, vacillation and decadence.

The only exception, perhaps the only militant book of this period is LuSin’s The Cry. This book played an historic role in the struggle against feudalism and was of tremendous influence in the further development of this struggle. It would be no exaggeration to say that this book has not lost its revolutionary significance to this very day. By stretching a point one could also mention Kan-Bai-Tsin’s book The Herb as having some militant traits of bourgeois romanticism, but after May 4 this “Herb” rapidly dries out.

As far as the collection of Hu-Shi’s poems Attempts is concerned, written in the new style, they are a mirror of Hu-Shi himself in which a glint of the bourgeoisie was reflected, but was quickly extinguished.

During this period there also appeared not a few satirical literary works criticizing the bourgeoisie and glorifying the workers (mostly poetry). The criticism of the bourgeoisie from its own ranks is usual and did not even attract any attention as it represented no danger to it; this is the so-called freedom of thought of the petty bourgeois intelligentsia.

From the 4th of May (1919) to the 30th of May (1925).

The 4th of May was defeated. The feudal militaristic government exists as before. A new ideology is not developed at once. For a few years from the “4th of May” .1919 to the “30th of May” 1925, there was a certain stagnation and uncertainty on the Chinese ideological front. And this condition was, of. course, reflected in literature.

“Wen-Sue-Yangtsuguy” (Society for the Study of Literature) was the first literary organization in Shanghai. Their demand “literature of blood and tears” was directed against the slogan “art for art’s sake.” But this was a petty bourgeois intelligentsia with a very vague idea of the “blood and tears” of the oppressed, and they had very little influence on the young generation, the only consumers of literature at that time. In addition the society produced nothing but critical articles expressing their literary views. To counterbalance it a new society arose—”Creation.” The members of “Creation” studied in Japan and were closely connected with Japanese decadence, but far from the mass movement at home.

In 1924, after ten years of existence of the “Creation” society there began a differentiation which drew part of its members closer to the proletariat, giving rise to the slogan of a “literature of the fourth class.” This group of writers were the pioneers of revolutionary proletarian literature in China. The other part of the membership of “Creation” went over to reaction.

At first the most prominent representatives of the “Creation” society were Go-Majo, U-Dafu, Chen-fan-u and Chjan Tsi-pin. On May 1, 1920 they began publication of their monthly magazine Creation.

During this period much foreign literature of the most diverse tendencies was translated. Here were impressionism and decadence, naturalism and realism, expressionism, in a word—chaos. Decadence was most popular. European decadence assumed a characteristic slant in Chinese literature. Go-Majo’s books for instance, his A Woman’s Soul, Fallen Leaves, etc., bear evident traces of decadence. Even the illustrations to the books were under its strongest influence.

But, while under conditions prevailing in Europe decadence corresponded to a period of decline, under conditions prevailing in China the peculiar angle decadence assumed was of revolutionary significance and played a revolutionary role with respect to the old feudal literature.

Go-Majo

Go-Majo is a talented writer of poetry, prose, drama, essays and an excellent translator of foreign literature. His literary activity falls into three periods.

The period from the “4th of May” 1919 to the movement of the “30th of May” 1925: During this period he stood for romanticism and decadence. The book A Woman’s Soul depicts the formation of the bourgeoisie. In poetry he was an urbanist. In his play Three Rebellious Women he exposed feudalism and urged women to rebel against Confucianism.

The second period of Go-Majo’s literary activity covered the entire period of the Great Chinese Revolution. During this period he wrote a number of essays and took part in the revolutionary movement by working on the staff of the then national revolutionary army. After Chang-Kai-shek’s treachery to the revolution Go-Majo wrote a sharp satirical proclamation against Chang-Kai-shek which he published in the urban press, upon which Chang-Kai-shek issued orders for his arrest and he emigrated from China.

Another brilliant representative of “Creation”—U-Dafu—was also an exponent of romanticism and decadence. A great craftsman, U-Dafu at one time put forward the slogan “suffering proletarians of all countries must unite”…without ceasing to be the sombre singer of pessimism. It is held in China that if Go-Majo is the representative of the foremost part of the young generation of the “4th of May”—U-Dafu represents the rest of them.

The Chinese proletariat and poor peasantry played a decisive role in the national emancipation struggle of 1925-27. Among the intelligentsia the differentiation continued. This also told on “Creation.” Go-Majo came continually closer to the proletariat. U-Dafu, on the contrary, capitulating, left the group and began to come out against it. The magazine Creation became so revolutionary that it was prohibited by the Kuomintang on February 9, 1929. Since then there has been a strong growth of revolutionary literature.

As far back as 1926 Go-Majo agitated for the creation of a class literature of the proletariat. He wrote: every class has its singer. Our literature must be permeated by the proletarian spirit. “You,” Go-Majo addressed the young writers, “must go to the masses, the army, the factory, into the thick of the revolutionary ranks. We must achieve the creation of such a literature as will reflect the hopes of the proletariat, be a realistic literature of the proletariat.”

Tsian-Guan-Chi

After Go-Majo another adherent of revolutionary literature appeared in China in the person of the poet and prose writer Tsian-Guan-Chi. From 1922 to 1924 Tsian studied in Moscow. On returning to China, Tsian began his propaganda for the creation of a revolutionary literature.

In Moscow Tsian wrote on Lenin, on October, on the Pioneers—all this was later published in China in a collection of poems New Dream. In China he wrote a book of poems Woe to You, China! Of his stories the best are “Young Wanderer,” “On the River Yalu” (Korea), “Party of Short Pants,” etc.

Tsian’s further development showed that having risen on the wave of the revolution to truly great heights he was able to depict the best aspirations not only of the bourgeoisie but also of the proletariat. He gave to Chinese literature the figure of Lenin, depicted the Soviet Union. Later Tsian-Guan-Chi left the revolution. For refusing to take part in practical work entrusted to him by the Party and for depicting the life of Whiteguards in China in a light giving a wrong conception of the Soviet Union he was expelled from the Party.

In 1931 he died of tuberculosis.

For a Revolutionary Proletarian Literature

Since the Spring of 1928 a number of new literary organizations. sprang up: the society “Sun,” “We,” and others which published their own magazines—Sun, Literary Critic, etc. These organizations and magazines came to one common slogan: “For a revolutionary proletarian literature.” They built up the theory of revolutionary and proletarian literature. In 1929 the literary movement was firmly established. A number of new magazines were published: New Trend published by the society “Sun” was prohibited after the third number, then renamed Tofanje (Pioneer). The magazine In-Tsin (Energy) conducted an ideological struggle against bourgeois literary theory. There was the weekly Hai-Iun (Wind from the Sea) which was also prohibited after 17 numbers. All these magazines called the toiling masses to the struggle against reaction and printed much international and especially Soviet literature. During this period there were translated and published in separate volumes: Sinclair’s Oil, Jimmy Higgins, King Coal, etc.; Jack London’s Iron Heel; Gorky’s Mother; Serafimovich’s Iron Stream; Gladkov’s Cement; Libedinsky’s Week; Sholokhov’s Quiet Don; Ognyev’s Diary of A Communist School Boy; Furmanov’s Mutiny; Lavrenev’s Forty-first; and many others. At the same time translations were made of Marx’s Capital vol. 1, and individual works of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Plekhanov, Lunacharsky, etc. This all had a great influence on writing circles. Chinese literature now watches Soviet literature with tremendous interest.

Chinese revolutionary literature grew steadily. There appeared Go-Majo’s 1911 and My Childhood, Gun-Binlu’s Miner, Dai-Pin-wan’s Night in the City, Hun Lin-fey’s Home, etc. Even bourgeois magazines and conservative publishers for commercial reasons were compelled to take up the writings of revolutionary authors because of their circulation.

At this time the magazine Tofanje, illegal since 1930, appeared; the magazines Danjun-Weng-i (Mass Literature), the organ Ishu-Tsuishe (of the Society of Artistic Drama), which was really the successor of Creation but with new forces. In addition there was the magazine Mun-ya (Embryo) in which the translation of Fadeyev’s Debacle was published and later issued in book form; the magazine Partisan the nature of which corresponded to the title; the magazine Niang-Go (Southern Country) continued to be published under the editorship of the well-known dramatist Tiang-Hang; the magazine Ishu (Art), later renamed Siren, etc.

What was characteristic for the end of 1930 was the tendency for the union of all forces to common work. The Shanghai club of proletarian art and literature reorganized itself into the Society of Proletarian Art and Literature—Hammer and Sickle.

The by-laws of this society are interesting. Here are some excerpts:

“The aim of the society is—the study of proletarian literature and art, the study of the life and manners of the working class, the furthering of proletarian literature among the masses and the bringing up of new proletarian writers from working class circles.

“Membership in the society is open to anyone wishing to conduct in practice the propaganda of Marxian literature among the masses.

“Structure of the society:

“The society consists of circles of five members in each. At the head of each circle there is an elected elder. Every three months a general meeting of members by districts is called.

“For new members short courses in Marxism-Leninism are instituted.

“The literary work of members of the society is published in the workers’ paper Shanghai-Bao in the ‘Club’ department and also in separate brochures.

“Preference is given to workers from the shops in the applications of new members. Members of the society must keep close contact with the masses and work in some labor organization, go to work at some factory wherever possible and there, in the process of the class struggle, hand in hand with the working class, forge their world philosophy.”

Organization of the League of Left Writers in China

In the Spring of 1930 there was a preliminary meeting uniting all left literary groups at which the work done until then was summarized and the problems facing the contemporary literary movement indicated.

Three fundamental tasks of the new literature were formulated: a relentless attack on the old society and all its ideologic manifestations; propaganda of the idea of the new society and work for its most speedy realization; working out the theory of the new literature.

The League of Left Writers of China having completed its organizational work announced its existence on March 20, 1930. It is now the only left, literary organization of revolutionary minded writers in China.

On the initiative of the League the All China Confederation of Left Culture was created in September 1930, which unites workers in all fields of art. At a unity meeting the following organizations were represented:

The League of Left Writers

The League of Left Artists

The League of Left Theatrical Workers

The League of Sociologists

The Union of Book Store Clerks

The Society for Research in Social Problems

The Literary Research Society

At this meeting the main question was of a common struggle for a new revolutionary culture, against the false, counter-revolutionary bourgeois landlord culture and against the White terror.

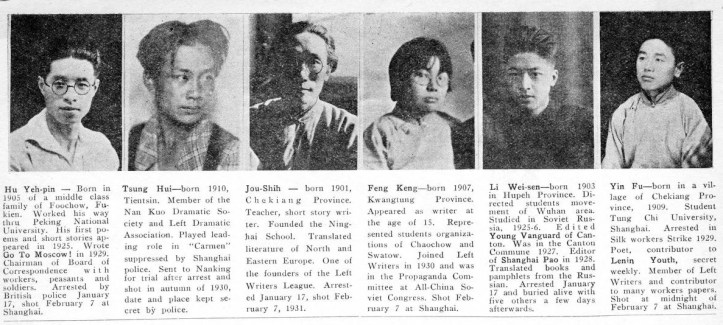

The Kuomintang imperialists are fully aware of the power of this left cultural movement and are trying to crush it by the severest measures, not stopping at mass murder. At present the movement has been driven underground.

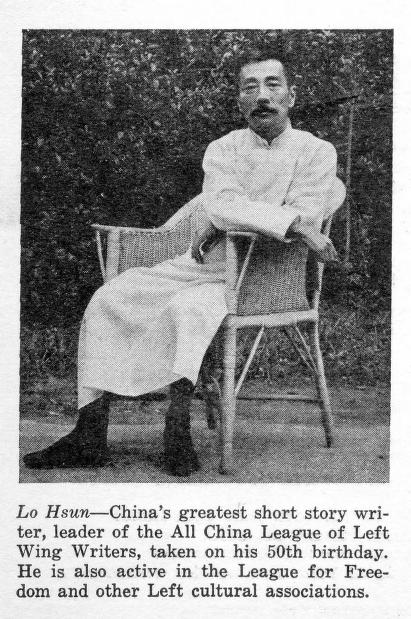

Lu-Sin

A great victory of the League of Left Writers, was the attraction to its ranks of a number of great artists, their enlistment in the struggle of the proletariat and poor peasants against international imperialism and its agency the Kuomintang, and for a Soviet government for all of China.

One of the greatest and most authoritative of Chinese writers, Comrade Lu-Sin, called the Chinese Chekov, for a long time doubted the necessity of creating a proletarian literature in China and during the entire revolution of 1925-27 kept aloof from the revolutionary movement. At the beginning of 1930 he came completely over to the proletarian side and became one of the founders and leaders of the League of Left Writers of China. Notwithstanding the persecution and hatred of the Kuomintang which have driven Lu-Sin underground he enjoys the same respect and authority in China as, say, Maxim Gorky in the USSR.

His famous book Truthful History of the Life of A-Q, translated now into English, Japanese, French and Russian, vividly and concisely describes the life and psychology of the Chinese peasantry and shook all China in the period of the “4th of May” 1919.

Lu-Sin has written more than 20 militant, artistic creative works, mostly stories. Here he appears as leader of the modernization of Chinese style and the pioneer of the small form—the militant short story, which previously did not exist in China.

Lu-Sin was the leader of a group in the magazine Ui-Sy (Verbal Thread), editor of the revolutionary literary magazines Mon-Ya (Embryo), Partisan, Crossroads, etc.

During 15 years Lu-Sin has written numberless militant satirical feuilletons. These are publicistic articles and notes reflecting every current event of importance in the life of Chinese society and reflecting the whole process of the struggle on the literary front for this period.

The League of Left Writers Grows Stronger

Only two months after its organization, on the 29th of April, 1930, the League called its first conference at which a number of decisions were arrived at. The principal ones were: a program for the publication of a weekly organ; to establish connections with Japanese organizations of proletarian literature; to take part in the First Conference of Chinese Soviets: to struggle against liquidational theories in literature; to organize meetings, lectures and discussions on literary subjects for the broad masses. Thirty members of the League took part in this conference.

A representative of the League of Left Writers took part in the Second International Conference of Revolutionary Writers in Kharkov. At the same time the League became a member of the IURW.

The organization of the League called out great alarm among the ruling classes. Along with the severest repressive measures against the ee confiscation of books, magazines, arrest and execution of revolutionary writers, the Kuomintang subsidized the so-called “national” literature. The League had to conduct a relentless struggle against this “literature.”

After strengthening its central organization, the League unfolded its activities in the provinces. A number of branches of the League were organized in the North and Central regions of China and Japan. Under the influence of the League various literary organizations of young writers arose in many places.

The League of Left Writers did a great deal to create a mass literature. Within the League itself a sector of mass literature was organized.

In November 1931, there were already 12 literary circles in Shanghai with a membership of about 200.

The mass sector works to develop. worker-correspondents. In 1932 there were in Shanghai four workers’ circles with from 20 to 40 workers in each. Ten members of each produced worker-correspondence regularly. Wall newspapers were organized at factories. In 1932 there were such wall newspapers in Shanghai in 12 enterprises and they were issued from two to three times a week, and occasionally daily. The. wall newspaper played a great role in the bus strike of 1932 in Shanghai.

During the campaign of protest against the Japanese occupation of Manchuria, the sector of mass literature issued a number of agitational-artistic productions—brochures, leaflets, songs, poems,—which are widely read and are convenient for distribution. All this was written in the form of folk songs, dear to the Chinese worker.

For the anti-war campaign on August 1 the League organized a competition on an anti-war work and a number of meetings where revolutionary writers spoke, conducted a symposium among Chinese writers on the subject: “What will be our position in the case of an attack of Japanese imperialism on the USSR?”

The League took an active part in the anti-war conference which took place in Shanghai underground in 1933, attended by the noted French writer Vaillant-Couturier.

The authority of the League among student youth and, the intelligentsia grew steadily. The foremost intellectuals went to the left. In this the publications of the League played a great role. In 1931 the League created its central organ Outpost, changing the name with the second number to The Literary Leader. Altogether nine numbers were issued. The magazine paid much attention to anti-imperialist mass literature and led a firm struggle against the so-called “nationalist” literature, calling it a “literature of executioners.”

The examples of mass literature printed in the magazine deserve attention. Some of them—songs, folk songs in form and anti-imperialist in content, songs against the Japanese occupation of Manchuria. These songs are interesting not only for their popularity but also for their having two texts differing neither in content nor in form but in the dialect—one text in the Shanghai dialect, the other in the Northern one. This bears witness to the fact that the League of Left Writers seeks and finds the way to the masses of worker and peasant readers. The Literary Leader was suppressed by the Kuomintang.

On The Literary Front 1931-32

In 1931-32 several more revolutionary literary magazines and newspapers appeared in China.

Crossroads—a satirical newspaper with sharp feuilletons, songs and serious critical essays. This newspaper was very quickly suppressed.

Literary and Art News—a weekly giving much information on questions of revolutionary literature and art. It was usually well illustrated with photographs and drawings. In June 1932 the weekly was confiscated and soon after that one of its editors, Comrade Lou Shi-yi was kidnapped by the Chang-Kai-shek “blue shirts.”

On June 20, 1932 the first number of Weng-Sue-Uebao (Literary Monthly) appeared. After only four or five numbers the magazine was suppressed.

Bei-Dow (Great Bear) was a solid monthly magazine devoted to art and literature whose editor was the highly talented woman writer, Comrade Ting-Ling. The first number appeared on September 20, 1931 and in September 1932 the magazine was prohibited.

The general situation on the literary front in 1931-32 was as follows:

The fascist “nationalist” literature was bankrupt.

Vacillating writers published essays on subjects like: “Study is Fruitless,” “Repent by Study”—reflecting their lost feeling and the impasse to which they had come. They did not produce a single notable work during these years.

Revolutionary literature grew in spite of the fiercest White terror, confiscation of books and magazines, arrests and executions of writers.

It was natural to expect anti-imperialist and especially anti-Japanese literature during these years. In this respect the “nationalist” scribblers gave absolutely nothing except formal declarations and some empty verses, while the chauvinist writers followed the line of the Nanking government of “nonresistance to the Japanese,” and against the principal enemies of the country, the “Communists and Russia!” Hou-Yao’s book Death of Hang Guandi describing the events on the Chinese Far Eastern Railroad is a vivid example of such literature.

The revolutionary writers produced many anti-imperialist plays: Tiang-Hang wrote Alarm, Sao-She, Seven Women Storming, Friend at War, etc. Lou She-yi wrote Life’s Way, SOS, etc. These plays were produced in all large cities in China attracting great attention and calling out great enthusiasm in the public. Appearances of theatrical troupes on the streets were organized.

To this literature should be added the work of the so-called “fellow travelers”: Chan-Tian-yi, Mo-Shi-yin, Shi-Chu-tsun. They produced a number of things describing the life of the petty bourgeoisie, soldiers, peasants, clerks and workers. Unfortunately they wrote only from the point of view of an onlooker.

The book of the well-known journalist Hu-Yudji, Moscow Impressions must be mentioned. This book gives an artistic description of what the author saw in Moscow in seven days and gives a fair idea of the Socialist construction going on in the Soviet Union. The book is now in its seventh edition.

In the revolutionary art and literary magazines much valuable work appeared: Short Stories by Ting-Ling—Water, That Night, on the shooting of some Communists, fragments of Mao-Dun’s novel Midnight, short stories and essays by Low-Shi-yi, Unemployed in Tokyo, by E-Lin, In the Village, (on the Shanghai war), Chjen Botsi, The Spy, News, General Retreat, (on the Manchurian events), etc.

The appearance of translations of Fadeyev’s Debacle and Serafimovich’s Iron Stream produced a tremendous impression in China.

April 23, 1932

The historical decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union of April 23, 1932 on the reorganization of literary and art organizations was of world significance. The old methods of work of the IURW were the methods of RAPP and this was reflected in all sections of the IURW. After the liquidation of RAPP there was a radical change also in the policies of the IURW.

During the summer of 1932 the Chinese League of Left Writers, after looking over its work, began to readjust itself.

As a result of a persistent struggle for obtaining the right of a legal existence the influence of the League on the literary front in China became much greater. The works of the members of the League penetrated into many bourgeois magazines, to the literary pages of general magazines and even into the daily newspapers. These works vividly reflected the proletarian world philosophy and exposed the cruelty and deceit of the ruling classes and their inevitable doom, hinting thus to the masses how to find the way out.

With the winning of legality began a real struggle against feudal literature. Among the students and the intelligentsia the League gradually displaced the influence of White literature. Members of the League became permanent contributors to various magazines.

The radicalization of the masses of readers compelled not only the colorless commercial magazines to acquire a somewhat “left” bent, but even the official White magazines (issued by yellow writers bought by the Kuomintang) tried to fool readers by pseudo-left articles. Here the Trotskyite and anarchist writers joined hands with the White magazines. The “New Moon” group led by Professor Hu-Shi, also joined them. However, although the Kuomintang spent large sums on general and literary magazines, these found no readers. For instance the Literary and Art Monthly, a magazine published under the immediate auspices of the Central Committee of the Kuomintang still comes out regularly but no one reads it.

The group of Wong-Tsing-Weh, utilizing several lumpen-literateurs, began publication of several art and literary periodicals in Shanghai; they put out the slogan “for a democratic literature,” and hid behind the sign “Art above all,” trying to deceive the reading public by all available means. Their efforts also came to nothing.

The colorless magazine Modern Age, stands on a liberal platform. But it has to obtain the work of League members in order to attract readers.

This does not mean, however, that the ruling classes of China have let the literary arms slip entirely from their hands. Not at all! Orthodox art and literature of the Chinese ruling classes, i.e., feudal literature, still has tremendous influence both among the city population and among the peasantry.

One sort of feudal literature—the so-called “Saturday literature” is still more popular among the city population than any other sort of literature.

This literature consists mainly of “illustrated short stories.” Booths where these illustrated books can be obtained are widely spread in all corners of every Chinese city and even penetrate to distant villages. In comparison to this literature the mass literature of the League is much weaker. An underestimation of the power and influence of feudal literature by the League of Left Writers—is a great mistake of the past.

The main task of the League, therefore, in its campaign for the growth of the worker and peasant correspondent movement is the emancipation of the laboring masses from the poison of feudal literature.

What 1933 Brought:

Mao-Tun’s novel Midnight; a collection of short stories by Mao-Tun—Spring Silk Worms; Ting-Ling’s book Mother; a collection of short stories by Ting Ling Banquet; a collection of the writings of the young author Sha-Tina Line Beyond the Law; Li Hweh-ing’s book Wangbao-Shang; a collection of short stories by Chan-Tiang-yi—Bee, and his novel One Year; a collection of short stories by Pu-nusy Short Shadow; three volumes of Lu Sin’s collected works.

The arrival of Bernard Shaw in China was utilized for anti-imperialist propaganda. The League issued a brochure Bernard Shaw in Shanghai.

In 1933 two collections of short stories by Soviet writers were published under the editorship of Comrade Lu-Sin who also translated most of them.

Mao-Tun

Mao-Tun is one of the most prominent writers of modern China. After completing a three year course at the Peking University, together with Chen-Chow, and organizing the “Society for the Study of Literature,” he was for some years editor of the literary magazine Short Story Monthly, published by the Commercial Press, where he spoke for naturalism in literature. Since 1924 Mao-Tun has been in the revolutionary movement and in 1926 he was a political worker at Uhan in the national revolutionary army.

In the Fall of 1927, that is, after the defeat of the Great Chinese Revolution, Mao-Tun began work on his Three Books of Life’s Experience (Vacillation, Disappearance, and Refound) depicting in part the events of 1926-1927, which at once put Mao-Tun in the ranks of the greatest Chinese writers. Then Mao-Tun wrote his unfinished novel Rainbow, two books of short stories, Wild Roses and Sumun, the book Three Persons, The Road, and in 1932 he published his best novel Tsan-E (Midnight). This last book, on the background of the civil war, deals with Chang-Kai-shek, the Northern generals, the competition between Chinese capitalists and industrialists and between Chinese and foreign capital, a strike of the workers in a silk mill and the role of the Communist nucleus in it, a peasant uprising and the rout of the landlord in the villages. The book is distinguished for its great power, high artistic craftsmanship and is considered the greatest achievement in Chinese literature for the past ten to fifteen years. Another work of Mao-Tun’s—the story Spring Silk describing the effects of the crisis on the peasant in the distant villages is also of great artistic value and has been filmed in Shanghai. (This story appeared in International Literature, No. 4, 1934— Editor.) Fall Harvest is the sequel. There the old peasant dying realizes that his son, who leads a peasant uprising is right.

Ting-Ling

The young, most talented woman writer Ting-Ling was kidnapped by the “blue shirts” at the foreign concession in Shanghai, handed over to the Kuomintang and after the cruelest torture was secretly done to death by the Kuomintang executioners in the summer of 1933. She was then only 26 years old.

Ting-Ling was one of a large ruined family. In 1924 she entered the University of Shanghai which played a leading role in the movement of May 30th. Ting-Ling studied literature at the University, but left it after one year.

She began publishing her work in the second half of 1927. Her first story, The Dream, appeared in the Short Story Monthly. After this Ting-Ling wrote Sophie’s Diary which also appeared in that magazine. Sophie’s Diary is an expression of the women’s rebellion against the feudal yoke.

Then Ting-Ling wrote a novel Weh-Hei (1929-1930) on the then fashionable theme of “Love and Revolution” which shows an advance in Ting-Ling’s ideological development. The subject of Ting-Ling’s next book Shanghai, Spring of 1930 is the mass movement in Shanghai in which the heroine of the book solves the conflict between “revolution and love” in favor of revolution. This book is similar to Weh-Hei except that Ting-Ling’s position in describing the foremost fighters became clearer. Soon after this Ting-Ling wrote her Village of Tiang, a description of the cruel class war in the village. The heroine—the daughter of a landlord—becomes a Bolshevik. From The Dream to the Village of Tiang Ting-Ling went a long way from individualism, anarchism, to the worker and peasant masses, to the new society.

Up to that moment Ting-Ling did not become a member of the League of Left Writers although her husband Hu-Eping was already active in the League. Ting-Ling answered the execution of Hu-Eping and four other revolutionary writers by going completely left and took the bloody road of the five revolutionary writers.

Beginning with the summer of 1931 Ting-Ling became one of the most active fighters of the League—a member of its executive committee. At that time all left magazines had been suppressed. The League issued a new, semi. legal magazine, its only organ, Weh-Dow (Great Bear) whose editor was Comrade Ting-Ling. Her important book Water appeared in this magazine. Water shows the further development of Ting-Ling as a revolutionary writer. The murder of Ting-Ling is a great loss to Chinese revolutionary literature.

China’s Literary Rostrum After the Shanghai War.

U-Dafu. If previously U-Dafu represented individualism, decadence, which still was of the nature of protest against feudal and! bourgeois culture, his work now shows a total capitulation to feudalism (thus, for instance, U-Dafu writes sympathetically of the village gentry addicted to opium).

E-Lin-Dung. City writer. His book Girls of the Age deals with the psychology of the petty bourgeoisie.

Ba-Tsin writes of the transition of the intelligentsia from sadness and grief to revolution. Psychological studies.

The “New Moon” group. After the death of the “sainted” poet Suy-Chjimo, Liang-Shi-tsu and Hu-Shi are its main leaders.

The special literary page of the newspaper Shenbo (Free Speech). Prints patriotic historical novels and poetry in ancient classical style.

The literature of “three principles” or the “Sun-Yat-Sen” literature is the literary policy of the Kuomintang. Announcing a competition it proposed six conditions, the fulfilling of which assures a prize. The main condition is: develop the national spirit, show the glory of China’s past history. The competition brought no results.

The special page of the newspaper Mingoje-bao prints “anti-imperialist” stuff by the “reorganizationists” (the Wang-Tsin-Weh group).

The “New Era” group, headed by the scribbler Tsian-Tsing-Ko. The magazine and individual publications of this group show its conservativeness and the extremely low level of its ideology and literature. Literally not a single significant work.

The Revolutionary Writers and the Theatre

The work of the revolutionary writers in the field of the theatre and the movies deserves special note. The theatre and the movies are especially significant for China in view of the illiteracy of the majority of the workers and peasants.

The first revolutionary play was A-Chen by the dramatist Gun-Binlu. A-Chen reveals life in the modern Kuomintang village.

In the past the League of Left Theatrical Workers limited its work to “Blue Blouse” appearances. The performances of the left theatre only began to be a factor among the broad public in 1933. In the Spring of 1933 Shanghai bourgeois circles inaugurated a month of grand concerts the proceeds of which went to aid the refugees from the North East province (Manchuria). The dramatic parts of these concerts consisted almost completely of plays sponsored by the League of Left Theatrical Workers. The plays of Tiang-Hani Friend at War (on the subject of Japanese intervention in Manchuria on September 18, 1931) were performed many times. The performances attracted tens of thousands of people who always responded warmly to these plays.

That year S. Tretyakov’s play Roar China! was performed in Shanghai. The play was twice translated into Chinese, but up to now it has been played only in Canton in 1930, and in Shanghai in 1933 where it made a big furore, and the name of the play became a favorite title for magazine articles.

The Cinema

Lately, a good many of our things have been filmed. The work of Comrade Tiang-Hani and others in this field has been very successful. The oldest and largest movie company “Min-Sin” (‘Star’) used to issue exclusively feudal, religious or adventure films, but this year they began to accept ideologically more progressive scenarios. The reason is, of course, the same as in the commercial magazines—the attempt to attract a wider audience. The most important film of the “Min Sin” company this year is the picture Stormy Stream on the subject of the flood in China of 1931. The scenario for this picture was written by a member of the League. Recently Mao-Dun’s story Spring Silk was made into a scenario and filmed by the “Min-Sin” Company. Lu-Sin’s Truthful History of the Life of A-Q is scheduled to be filmed soon.

Another movie company “Liang-Hua” has issued a film on a scenario based on Tiang-Hani’s Three Modern Girls which attracted much attention.

This year this company has filmed City Night and City Morning. Both pictures tell of the evils of cities putting forward the reformist slogan “back to the village.” The League of Left Writers and the League of Left Theatrical Workers are offering strong resistance to such propaganda.

The talented story by Low-Shi-yi Salt Field, published in the magazine Pioneer in 1929 and describing the uprising of the workers in the salt fields, the exploitation of the workers and peasants by the landlords, owners of the salt fields and their Kuomintang government, has been made into a film. Low-Shi-yi’s play SOS (on the theme of anti-imperialism) has been produced by the workers of the radio-broadcasting station.

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1934-n05-IL.pdf