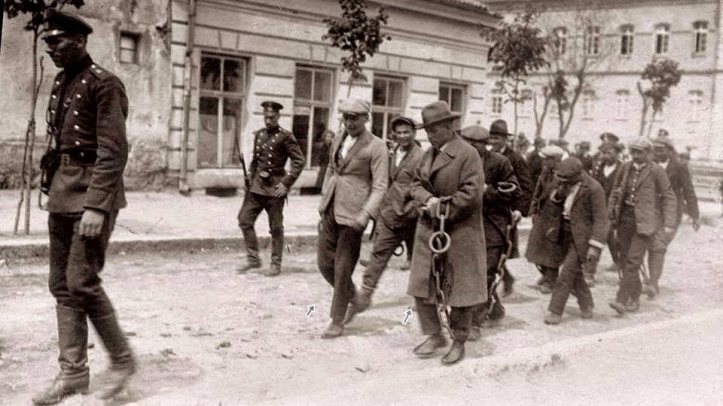

Koloarov with a useful article in understanding a turning point in 1920s Europe–the June 9, 1923 overthrow of Agrarian Party leader Aleksandar Stamboliyski by the Bulgarian military, instituting a reign of terror under the White Guard rule of Aleksandar Tsankov. At the time the Bulgarian C.P. was one of the most influential in the world, a genuine mass party it was the largest single Party in Bulgaria and failed to intervene in the coup. Repression was met with lost armed risings, followed by guerilla operations, and then terrorism with the Bulgarian C.P., as it was, destroyed in prison, exile, and the grave over the next years. A generation of revolutionaries wiped out.

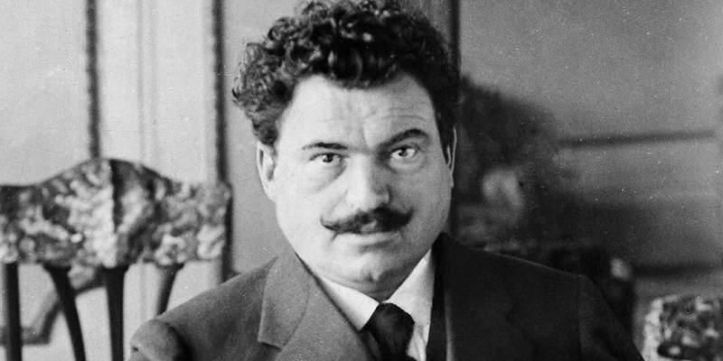

‘The Social Basis of the Zankov Government’ by Vasil Kolarov from International Press Correspondence. Vol.5 Nos. 70 & 71. September 17 & 24, 1925.

1. The Economic and Social Structure of the Country.

Bulgaria has a population of approximately 5 millions, 80% of which is in the villages and only 20% in the towns. The density of the population is 74 to the square mile. The peasant population is divided amongst 5560 localities, the average number in each locality being 700. There are 92 towns, of these only the capital Sofia has over 200,000 inhabitants, two other towns have from 50-100,000 inhabitants and six further towns from 20-50,000 inhabitants. These figures prove that Bulgaria is preponderatingly a peasant country.

A considerable section of the population in some of the peasant districts, such as Perschin, Gorno-Oryechov etc. works in the mines and in the industrial undertakings there, and a not smaller section of the town population is engaged in agriculture. In 1910, 81% of the active population was engaged in agriculture and its allied branches. The present situation is not considerably different to that before the war, as in this period industry has made no particular progress.

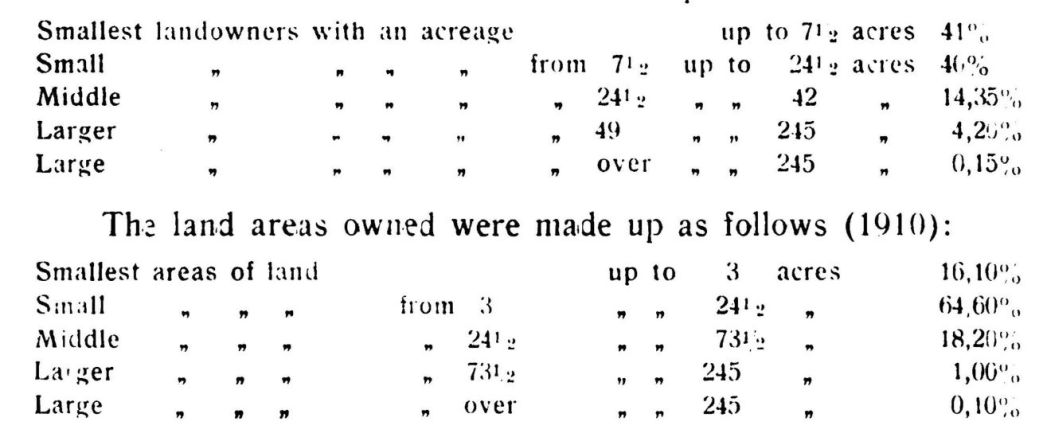

In 1908, the total area of land under cultivation amounted to 19,716,653 acres; of these, 11,436,305 acres were in private hands, divided between 705,820 owners. According to the area of land owned, the owners were made up as follows:

Large It is impossible to determine with accuracy the alterations which have taken place since the war. But without doubt the process of proletarisation has been strengthened. The general decay of agriculture and the derangement of peasant economy have both contributed to this. The relation between the large landowners and the other social groups in the village was altered to the disadvantage of the former by the loss of the Dobrudja, where at least one sixth of the large landed estates were concentrated. The land reform of the peasant government brought no important alterations with it, since it has gone over into the hands of the white guardist government. Up to the end of 1923, 120,905 acres of private land were expropriated and 80,430 acres of public land. The right to this land was recognised in the case of 79,527 landless and poor peasants, but only 780 persons finally received a total of 34,217 acres, or 43.14 acres each. After the overthrow of the 9th June, the expropriation ceased and a part of the redistribution was annulled.

The economy of the small owner is very primitive. The machine and even the plough have not yet made their way into the Bulgarian villages. To each 49 acres there is one iron plough. The greater part of the small proprietors possess no draught animals. In 1920, from a total of 641,744 peasant undertakings, one fourth possessed no draught animals and only one third possessed carts etc. This small-holding economy can only exist by the cultivation of tobacco, which is possible on a small area of land but which demands a great expenditure of labour power. In 1923,191,800 undertakings cultivated tobacco, that is, 30 per cent.

The Bulgarian bourgeois economists point out that a welcome transition is taking place from extensive agriculture (cereals) to intensive (Tobacco etc.). But they naturally overlook the derangement of the small peasant economy, the rising exploitation of woman and child labour and the overloading of the small undertakings with mortgages held by commercial capital. Whilst in 1924 the wholesale price for bread cereals had reached to 30 times its pre-war level, in the same period the price for tobacco had risen only around 6 or 7 times its pre-war level. It is clear that the small peasants, in consequence of their lack of land and working animals, have gone over to the production of tobacco, despite the fact that this latter is less advantageous. This disadvantageous situation is utilised by the tobacco exporters, who have become one of the most powerful groups of capitalists in the country. According to an approximate calculation, in the last five years they have enriched themselves at the cost of the poor tobacco producer to the extent of three milliard Bulgarian levs.

Industry is still in its embryonic stage. With very few exceptions it is concentrated in the towns: the textile industry in Sliven and Gabrov, the sugar industry in Sofia and Philippopolis, Ruschuk and Gorna Öryechoviza, the tobacco industry in Philipopolis, Chaskov, Dubniza etc. Before the war, industry developed rather quickly, since then however it has come to a complete standstill. The census of 1922 showed that there were 1,541 industrial undertakings using over 10 horse-power in which 55,300 workers were permanently employed. A sum amounting to 5,758 Bulgarian levs was invested in them. The tobacco industry employed 19,815 workers or 35.8 per cent. The mines 9,642 workers or 17.4 per cent. The food industry 7,543 or 13.6%. The metal industry 4,482 or 8.1%. Practically the industrial army, including its reserves, totalled round about 80,000 men. It must be pointed out that since the war the national industry has been going over more and more into the hands of foreign capital, which enters the country, not to develop the productive forces, but to carry out unlimited exploitation. The Bulgarian industrialists, who enjoy no credit, have either sold their factories or turned their businesses into joint stock companies; in one form or the other they have come under the control of foreign capital. The anxiety of the Bulgarian industrialists for the revolutionary movement also contributes to this process, for in order to avoid the risk, the capitalists invest their money under a false flag. The chief national industrial branches the milling and tobacco industries are already completely in the hands of foreign capital, and soon the leather, textile and spirit industries etc. will follow them. The war furthered the concentration of large capital, which however was not invested in an industry in the throes of a crises, but in speculation which opened up undreamt-of possibilities. Both the external and internal commerce is almost completely concentrated in the hands of the joint stock banks and companies. At the end of 1922 there were 531 such undertakings with a total capital of 1,395 million levs. From the joint stock capital, 58.7% was invested in commerce (Bank, credit and currency institutions etc.), 2.6% in mining, 36% in industry, 2.3% in agriculture and cattle breeding and 0.4% in transport.

In 1924 foreign capital was represented in Bulgaria in 51 joint stock companies with a total capital of 410 million levs. Of this the eight banks accounted for 182 million levs, the 19 industrial companies 135 millions and the 19 commercial companies 82 millions. The entrance of foreign capital after the war also takes the form of capturing the internal commerce. A great part of the imports and exports goes through foreign firms which have set up their branches and agencies in the country. The total foreign trade in 1923, both export and import, reached 8,650.8 million levs. The imports for 1924 divide themselves as follows: 78.2% factory products and 14.7% raw materials and half-manufactured articles. The exports: 56.1% bread, cereals and food and 34.8% for raw materials and semi-manufactured products.

In consequence of the weak development of industry, handicraft still occupies a large place in the national economy. The handicraftsmen form a rather numerically strong class chiefly in the towns. But the general crisis of industry and the lack of credit in 1922 from the total sum discounted by the Bulgarian National Bank, only 1.4% fell to, the share of handicrafts result in the speedy ruin of the handicraftsmen. Nevertheless, a great number of wage workers are engaged in handicraft.

Reliable figures upon the class composition of the population of Bulgaria are not available. The figures given in the “Yearbook” of Varga are, it is true, taken from the official Bulgarian statistics, but they give a false picture of the social groupings in the country.

The following figures are approximately correct concerning the social grouping:

Proletarians 29%

Semi-proletarians 12%

Petty-bourgeoisie 40%

Middle- 16%

Large- 3.5%

From what has been previously said the following conclusions may be drawn:

1) Bulgaria is preponderatingly a peasant country, an agricultural country with small property owners. Nevertheless, the towns, although small, play a comparatively great role as centres where the economic, political and cultural life concentrates.

As a consequence, the organised state power, despite its low numerical strength, has a comparatively great significance.

2) The diffusion of the small producers in small groups and their economic independence of one another considerably reduces, despite their numerical strength, their influence upon the economic and political life of the country.

3) The proletariat, concentrated chiefly in the town, has, although it is not numerically strong, a great significance as the leader and the advance-guard of the semi-proletarian small property-owning masses. Its division amongst comparatively small industrial and handicraft undertakings is to a certain extent compensated for by the existence of solid and active trade union and political organisations.

4) Large land ownership is insignificant and the large landowners play no independent and leading role.

5) The town bourgeoisie, despite its numerical weakness, has a comparatively great economic and political power. The chief role is played by bank and commercial capital.

6) From its relation to foreign capital, Bulgaria is a colony. Despite this however, the Bulgarian capitalists use the foreign control in order to strengthen their position against the toiling masses.

2. The Forces which Carried out the Coup d’etat.

Stambulisky came to power after the elections of the 17th August 1919, which gave the Peasant League a relative majority in the parliament. For the formation of the government he was compelled to seek support from other parties. A coalition with the Communist Party, the second strongest party in the country, was at that time out of the question. But for a number of reasons, a coalition with the menshevists also did not take place. Stambulisky preferred a combination with the considerably weakened and less exacting progressives and narodniki. The first named entered the peasant government in their capacity as agents of the capitalist class.

After the suppression of the transport workers strike (December 1919 to February 1920), Stambulisky believed that he had weakened the Communist Party, and so he dissolved the Parliament and set the new elections for the 28th March 1920, in the expectation of gaining an absolute majority. But his expectation came to nought, the Communist Party increased the number of its representatives from 47 to 50, and in order to maintain itself in power and to continue governing the country, the peasant government was compelled to resort to bargaining with a certain number of the oppositional representatives.

Some time later a right wing formed itself within the Peasant League and called for a co-operation with the bourgeois parties and threatened to break up the peasant government from within. In order to save the situation, Stambulisky once again dissolved parliament and, after a previous alteration of the electoral system, set the new elections for April 1923. This time the Peasant League received a crushing majority in parliament and its parliamentary situation was consolidated. But only a month and a half later followed the white guardist coup d’etat.

The influence of the Peasant League upon the masses of the peasantry was incontestably greater, and the number of votes cast for it rose from 203,773 in 1919 to 346,949 in 1920, and in 1923 reached 437,000. Despite this, however, it did not receive an absolute majority of the votes cast. It was therefore compelled to seek for support either from the town capitalist bourgeoisie, i.e. from the Right, or from the working class, that is, from the Left. But the unequal social composition of the Peasant League made it impossible for Stambulisky to declare definitely either for the bourgeoisie or for the proletariat. Instead, he manoeuvred and changed his front from time to time. In this way, dissatisfaction with the peasant government grew both from the Right and from the Left, and at the same time the government also failed to satisfy the masses of the peasantry which supported it.

The capitalist bourgeoisie was used to commanding the state and working with state means. Under the government of Stambulisky, however, it was compelled to suffer its humiliation and to content itself with the crumbs tossed to it by the State, and very often it had to make real sacrifices in order to save its vital interests at all. The interests of all capitalist groups were threatened. The land reform perceptibly disturbed the “sacred rights of property” of the large landowners, that is those owners who did not cultivate their land themselves. Only the overthrow of the peasant government could restore their threatened property. The house owners had also suffered. A not inconsiderable number of buildings was expropriated for the use of the state and public societies with only a minimal compensation. And those owners who were not expropriated could not exploit their property according to the bourgeois law of supply and demand, for the tenants enjoyed the protection of a special law. For this category of capitalists also, salvation lay in the overthrow of the “peasant tyranny”. The peasant government declared that it did not persecute industrial capital, nevertheless, the industrialists also felt themselves to be in danger, first of all because the Peasant League, conscious of its power, cast its eyes upon the milling industry and declared that it must belong to the peasantry, and secondly because industry received no sufficient amount of credit from the national bank. And finally, because industry was practically in the hands of the banks which dictated their attitude to the industrialists.

Naturally, the most perceptibly hit was bank and commercial capital. Stambulisky inflamed the hatred of the peasant masses against the speculators and the bankers and prepared the moral preliminary conditions for drastic action against them later. But apart from this, the peasant government, by a number of state measures, threw down the gauntlet also to large commercial capital. In 1919, for instance, it founded a consortium consisting of agricultural co-operatives and state banks, to which it gave the commercial monopoly for bread cereals. That was a terrible blow for the large bread cereal exporters who previously had formed the strongest capitalist group in the country. Two years later however, they were successful in abolishing this monopoly by the intervention of interested foreign firms and by the action of the Reparations Commission. But after this defeat the Peasant League did not give up the fight: the government attempted to form a consortium which would in fact have the monopoly in virtue of the credits issued by the state banks.

Under the peasant government the policy of the banks became ever more and more fatal to the interests of private commercial capital. The latter was clearly unable to carry out its gigantic operations in the purchase and in the export of the cereals, tobacco crop etc. without far reaching credits from the financial institutions of the State. In 1921, for instance, 73% of the total amount discounted by the Bulgarian National Bank went to the credit of merchants, banks and commercial companies and only 7% to the peasants. In 1922 however, the proportion was reversed, and the former received only 20% of the total bank credit whilst the latter received a full 52%. In the same period the credit of the industrialists rose from 11.6% to 12,5. The peasant government had, however, by cutting off the bankers and large commercialists so ruthlessly from their gold supply, made these latter into its sworn enemies. And in fact Bank and export capital stood at the head of the struggle against the peasant government. It mobilized the rest of the dissatisfied capitalist groups around it, and the whole capitalist bourgeoisie, strengthened by the large landowners and the owners of house property, took up the struggle against Stambulisky. That was very much, but not yet all. It was necessary to draw still other social groups into the fight and to work out the necessary programme to make the struggle into a struggle of the “whole nation” and what was most important, to organise a sufficient armed power and to win over the army. The large bourgeoisie quickly closed its ranks under the hegemony of bank and commercial capital and set to work. It proclaimed itself as the “Bulgarian People”, declared its interests to be the “interests of the people”, and raised the banner of the “People’s Alliance”, to which it called all Bulgarian and all Parties, with the exception of the members of the Peasant League and the Communists. A conspirative political organisation, the “People’s Alliance”, was led and financed by the bankers and large merchants. The military organisation of the overthrow was placed in the hands of the Officers League.

What social groups responded to the appeal to found the “People’s Alliance”?

First of all–the bourgeois intellectuals. The winning over of this group was of particular importance as a great section had served during the war as reserve officers. The rule of the Peasant League, which pushed the peasant half-intelligencia into the foreground, had abolished the educational conditions for the holding of most posts and in this way it had laid hands on the privileges which guarantee the existence of the educated intelligencia. Naturally, this latter group was indignant at the advance of “ignorance” and “peasant lack of culture”, and set all its hopes upon a restoration of bourgeois government. In 1922 a conflict took place between the government and the Professors of Sofia University. The latter had received support from the banks for the previous six months and sought to influence the students. The alliance of capital with “science” was completed. The Peasant League regarded the legal profession, from which the majority of all party leaders had come, as the source of all evil. And upon its accession to power it commenced to fight the latter systematically: it abolished the institute of lawyers in the civil courts, it limited their right to appear before the military courts etc. The lawyers, hit so keenly, placed themselves in the front ranks of the struggle against the peasant government. At the same time the government threatened a section of the doctors with distribution to the villages, in order to supply medical aid to the peasants. In this way it brought the doctors into the ranks of its enemies.

The attitude of the officers, both in the active list and on the reserve, was of special importance. Before the War the sons of Mars had enjoyed exclusive privileges which no one had dared to touch. The peace treaty however which disarmed Bulgaria, was a catastrophe for the Officers Corps. The greater section was on the streets and the defeat and the coming of the general crisis influenced the privileges and the prestige of those officers still in the service. In consequence the dissatisfaction amongst the officers was very great, and upon this basis there were serious conflicts between the government and the Officers Corps. In order to guarantee the safety of the Gendarmerie, Stambulisky began to make supporters of the Peasant League, ex-sergeant, majors etc. into officers. In the army he utilised the non-commissioned officers. A great section of the active Officers Corps maintained its enmity towards the government to the end. With regard to the dismissed officers and non-commissioned officers, these were compelled to rely upon state posts for which they could only hope after the overthrow of the peasant government. With this the Federation of Officers and non-commissioned Officers was practically an organisation which prepared the overthrow, and it therefore formed a support of the Officers League.

A second support of the League was the Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation. The peasants were the least nationalist and after the defeat, the least inclined for war. In consequence it was easy for Stambulisky to declare that the “National Ideals” of the Bulgarian People were buried, and therefore to give up all claims to Macedonia and to pursue a policy of reconciliation towards Jugoslavia. But just this policy turned the nationalist elements against him, and they sought to maintain Bulgarian Nationalism under the cloak of the Macedonian Organisation. It was not difficult for them to confuse the mass of conscripts in the Macedonian Organisation and to mobilise them in the name of “Macedonian Autonomy” against the Peasant Government.

The petty bourgeois, workers, employees and working inteliigencia of the towns in the main did not support the overthrow. A section of the handicraftsmen was even sympathetic towards the Peasant League. Those of them who belonged to bourgeois parties strengthened their passivity. It was however, a different matter when the overthrow was an achieved fact. A great section of the handicraftsmen and small dealers, oppressed by the heavy taxes, believed in fact that the overthrow would really bring them “freedom”, and so they greeted it with joy and hope. But this illusion lasted but a very short time. The reality quickly opened their eyes. The same was true of a section of the state officials. Pauperised and the object of continuous attacks and injustices on the part of the government, which also limited their right of combination, they set all their hopes upon the overthrow, but their disappointment followed still quicker. Among the working class, naturally the overthrow produced no particularly cheerful spirit. The terror of the Peatant Government against the workers had been hard, despite this however the latter grasped the fact that the overthrow had given back the power into the hands of their most deadly class enemies, the capitalist bourgeoisie, and in their great majority they were prepared to fight to the death against the overthrow. Unfortunately, the Party, surprised and disorganised by the unexpectedness of the overthrow, did not come forward actively enough and failed to lead the masses in the struggle.

The bourgeoisie could win neither the petty bourgeoisie nor the working class to an active participation in the overthrow. And apart from this it needed neither of them. Its programme of a “Peoples Alliance” was only a mask. It did not need the masses of the people, but well-organised conspirative groups and fighting units. And when it was successful in creating these and in being able to rely upon the support of the army, the Macedonian revolutionary organisation and the Russian monarchists, then the coup d’etat itself was a detail. With regard to King Boris, he was a sympathising prisoner in its hands. In this it received the active diplomatic support of Italy and England.

3. The Constitutional Parties and the Coup d’etat.

The bourgeois and the petty bourgeois parties took, “as such”, no direct part in the overthrow.

Not because the leaders of all parties with the exception of the social democrats were at that time either already sentenced or were under detention; no, the reasons for this lay deeper.

These parties even the most open defenders of capitalist interests, amongst them the National Liberals and the Peoples Progressives had a considerable section of the petty bourgeoisie and a great number of job-hunters in their following. The latter formed usually their most active groups. And this circumstance inevitably stamped its mark upon their politics and tactics.

The capitalist elements in them were clearly body and soul for the overthrow, but were not in the position to draw their parties with them, the organisations of which were in no way suited for a forcible seizure of power; they were only suitable for throwing sand into the eyes of the petty bourgeoisie. The latter willingly followed the large bourgeoisie when it talked about “law and order”, “freedom and democracy” and other beautiful things, but could not make up its mind to start with it on the dangerous road of the coup d’etat.

An overthrow brought about with the assistance of the Military League had also nothing particularly attractive about it for the job-hunting element. The latter knew that its worth to the parties depended upon its service, and it was therefore particularly active at elections, meetings and such political demonstrations; should however the overthrow come about, then the military would play the chief role in it and would then naturally occupy all the more important posts. And so this rather influential groups which often paralysed party connections and coalitions in its group interests, was also not particularly in favour of the agitation for the overthrow.

But also the general staffs of the parties could not decide to draw their parties into a support of the military overthrow. For they stand upon the basis of “legality” and upon the “constitution”, and oppose their “evolutionary theory” and “peaceful methods” to the “fatal” theories and methods of the revolutionary parties. What would remain of their “constitutionalism” and their “legality” if they themselves were to raise the banner of “revolution”? This applied most of all to the parties of the radicals and the social patriots, who preached “democracy” and “reformism” of the first water. Apart from this, an overthrow brings with it a certain risk for the parties engaged in it, as in case of a failure they are then subject to the reprisals of the governmental power. If, on the other hand, the undertaking is successful, then the parties can attach themselves to it without in the least injuring their “constitutional principles” and can proclaim once again the era of “law and order” to calm the frightened petty bourgeoisie.

And so the constitutional parties remained outside the conspiracy also for strategical reasons. But the special organisation which prepared the overthrow the “People’s Alliance” contained the individual leaders of all parties, including the social democracy. The plans of the adventure of the “People’s Alliance” and the Military League went however further: by isolating the old and, in the eyes of the masses of the people, strongly compromised party leaders, they hoped not only to gain these masses, but also to replace the “old statesmen” of the opposition by new men more agreeable to the bourgeoisie.

But the idea of the coup d’etat first arose when it became clear that the bourgeois parties and their petty bourgeois following were unable to overthrow Stambulinsky. All this time they had conducted an energetic struggle, they had reorganized, united and consolidated themselves and adopted new programmes. For instance, all the liberal parties, there were three, had amalgamated into one National Liberal Party; the People’s Party and the Progressive Liberal Party had united into a Progressive People’s Party. The attempt to extend this amalgamation so as to include the Radical and the Democratic Party was unsuccessful, but nevertheless, these three parties formed the so-called Oppositional Block, which in practice also included the mensheviki. The “Oppositional Block” adopted the programme of the National Party as its own and stood at the head of the struggle for the overthrow of the peasant government by “constitutional methods”. For this purpose it called meetings, organised demonstrations, issued declarations and called upon the king to exercise his “constitutional prerogatives” and dismiss Stambulisky. The republican menshevist jurists “proved” convincingly that King Boris possessed this “Right”.

With all this, however, the oppositional party leaderships did not boycott the conspiracy. They entered willingly into negotiations with the Wrangel monarchists to ensure the co-operation of the latter in case of necessity. The connections between the Russian white guardists and the Bulgarian bourgeoisie date from this time, connections which were later strengthened by the martial law which was held over the heads of both the Bulgarian working class and the peasantry. The bourgeoisie was particularly intimate with the Macedonian “revolutionaries”, whom it later used as the hangmen of the Bulgarian people. The bourgeoisie set the greatest hopes upon them as an armed power. With unconcealed pleasure they received the news of the taking of the town of Nevrokop by the Macedonian organisations, and later also the occupation of the town of Kewstendil, which was actually to form the signal for the insurrection against the peasant government.

The hands of the bourgeois and menshevist “constitutionalists” were by no means free from conspiracy even at the time when they still led the struggle. Even the well-known “Tyrnover events” in 1922, which turned out so sadly for the leaders of the oppositional block, were in close connection with the preparations for the insurrection.

After a series of failures, after the arrest of the oppositional leaders, and particularly after the heavy defeat of the “Block” in the elections of April 1923, the party leadership finally made room for the men of action, the people from the “Alliance”. After the coup d’etat was an achieved fact they attached themselves to it.

4. The grouping of forces and the perspectives.

It is perfectly understandable that the large landowners and large capital today inspire the policy of the white-guardist government. The first task of the latter was to abolish the “anti-constitutional” laws. Under this ambiguous term, which the June conspirators presented as the liquidation of the constitution, were all laws passed by the peasant government which directly or indirectly laid hands on the rights of property “laid down” in the constitution. The agrarian law which affected the rights of private property owners was declared as “anti-constitutional” in every paragraph by the bourgeois jurists; further, the law upon the expropriation of private buildings for the good of the state; the law which limited the “freedom” of the house owner to exploit his tenants etc. A tax reform law was carried through which considerably reduced the direct taxation of large capital and unbearably increased the taxation of the peasantry and also the indirect taxes.

The government paid particular attention to the interests of commercial capital. The consortium for dealing with bread cereals was completely abolished and the peasant syndicate which went with it was liquidated. The credits for the peasant co-operatives were cut off and the means of the National Bank were placed exclusively at the disposal of large capital. Speculation was declared a normal phenomenon and the struggle against it as dangerous demagogy. When, under the pressure of the suffering masses, a law was passed allegedly against the increase in the cost of living, the leader of the governmental fraction in the parliament Liaptchev, declared that the law was a “law for the fools”. Under such conditions speculation naturally flourished and prices rose immeasurably. The cost of living index rose from 3.187 in August 1923 to 4.039 in August 1924. At the present time it is over 5000. Added to this, in the last two years the Bulgarian lev has only sunk 25%. In consequence of their tremendous profits which called forth the dissatisfaction of the masses of the people, the speculators were dubbed “robbers without weapons”. To all this, the government naturally remained indifferent.

The government also eagerly attended to the interests of the industrialists. They also received large credits from the state banks. In all strikes the government naturally stands upon the side of the employers, and when necessary sends the armed forces imo action. When the laws for the protection of the worker are violated however, the government is blind and the trade unions of the workers have been disbanded. In conflicts between the sugar and tobacco exporters on the one hand and the peasant producers on the other, the government stands upon the side of the former.

It is clear that such a policy of the white guardist government provides no occasion for a break between it and the large bourgeoisie; and the same applies to the furious struggle which the government has now carried on for two years against the “bolshevist danger” and the “united front of the communist and the members of the Peasant League”. On the other hand the failures of Zankov’s foreign policy, which endanger the hopes of the bourgeoisie to carry out an economic and financial stabilisation through a revision of the peace treaty and the conclusion of a foreign loan, cause the bourgeoisie to consider seriously a possible change of ministers. This question is also connected with the bloody deeds of the government which have opened up a chasm between it and the masses of the people. In bourgeois circles there are voices in favour of a change in persons and methods which will consolidate the gains of the Zankov government and ensure the continued dominance of their class interests in the administration of the country. The handing over of power to the “left” parties would, however, by no means appear as a desirable change to the bourgeoisie.

The white guardist government has succeeded neither in winning the sympathies of the town and country petty bourgeoisie nor at least in rendering them patient. Regarding the masses of the peasantry there is nothing to be said. They have not reconciled themselves to the new power, but they are full of bitterness against it. The bourgeois parties accuse the peasant government of having incited the peasants against the towns. But no one has done so much towards deepening the chasm which now lies between a powerful section of the peasantry and the bourgeoisie of the town, as the government of the generals and professors. And this has been done, not only by the terrorising of the peasantry, but also by the economic and taxation policy of the government, which makes the working peasant the object of exploitation of a predatory capitalism and loads him with taxes. The handicraftsmen and the small dealers in the towns have also clearly expressed their dissatisfaction with the new government by arranging, for the first time in Bulgaria, a protest strike. The strongest argument of the opposition against Zankov is that his government is driving the petty bourgeoisie into the arms of the “destructive elements”, and in this way creates a danger for the state. In the meantime it is more than doubtful whether the legal opposition will be able to raise the sinking prestige of the bourgeois power in the eyes of the peasant masses. The responsibility for the bloody deeds of Zankov lies also upon its shoulders.

A representative of the Social Democratic Party was also taken into the cabinet of Zankov, before all in order to win the workers for the party of the overthrow. But the calculation proved to be false. The influence of the mensheviks upon the masses was very weak. At the same time the government proclaimed itself as the “protector of labour” and even introduced a little later a “labour law”, which earned for it the praise of Mr. Albert Thomas. But all these beautiful words and laws remain at

mockery in the face of the inexpressible suffering of the working class against which Capitalism and the government, from the first day on, had declared war with hunger and bullets. The indignation of the workers against the government was so great that even the corrupt Social Democratic Party felt itself compelled to withdraw from it. The proletariat was and remains the deadly enemy of the white guardist society; and not even the social democratic syrens are able to win the sympathy of the working class for the government. The hopes which these traitors set upon the dissolution of the Communist Party and the trade unions and the physical extermination of the active communist members in this latter respect they heartily did their share have not been realised. The workers have remained thoroughly estranged from their party and nourish a revulsion towards the menshevik jackals which is not to be overcome.

What are the relations between the heroes of the 9th June and the “constitutional” Parties?

The latter triumphantly greeted the coup d’etat, described it as the “greatest date” in the modern history of Bulgaria, and afforded the government their full support in the suppression of the insurrection of the people which flamed up. But immediately afterwards the conflict began. The old party leaders and their staffs considered the government of Zankov as a temporary revolutionary government and hoped after the consolidation of the situation for the formation of a legal government of the bourgeois parties. The military junta however, which had the actual power in its hands, did not even think of surrendering it to the anemic bourgeois parties. As nevertheless, they were needed to maintain the appearance of constitutionalism, it was decided simply to requisition them in the interests of the State. Two months after the overthrow the Progressive Peoples Party, the Democratic and Radical Party joined the “People’s Alliance” under the pressure of the bourgeois elements in them and under the energetic urge of the Macedonian organisation. A new governmental party was formed, the “Democratic Alliance”, under the nominal leadership of Zankov. The National Liberal and the Social Democratic Parties remained as independent parties within the governmental coalition.

That was the culminating point of the amalgamation of bourgeois forces which was necessary in order to set the crusade against the Communist Party into action and to ensure the success of the government at the elections.

Thereupon the process of disruption commenced. First of all, the coalition collapsed: the national liberals left the government and later the social democrats; the Radical Party left the “Democratic Alliance” almost completely, as did also the Democratic Party in its petty bourgeois section. Over and above this, the considerably reduced “great public power” upon which the “unity” of the people and the “renewal” of the state are based, is torn with internal rivalry and dissension, and Zankov, the “arbiter of fate” can at any moment find himself isolated with his fifty accomplices from the old “Peoples Alliance”. The white guardist government has destroyed the organisations of the workers and peasants, but in the last resort the bourgeoisie is also politically disorganised. In the place of the five legal parties which existed before the coup d’etat there are now ten legal bourgeois and petty bourgeois groupings (without the members of the Peasants’ League and the Communists).

What is the condition of the military forces of Zankov? The Military League continues to exist. As recent events proved, it is still all-powerful. Its members occupy the most important state posts. But the alterations and re-groupings which have taken place in the country have not passed over the League without having traces behind. One section of the Reserve Officers’ Corps remained discontented. The split in the “Democratic Alliance” also weakened the internal solidity of the League itself. It is also threatened with a split. The powerful Macedonian Organisation of the year 1923 is today little more than a ruin. After the events of September 1924 it is no longer in a position to place itself at the disposal of the government as a united band of cut-throats. The army remains: with whom does the army go, that is the officers’ group? The decomposition and disruption all around unceasingly weakens the unity of the officers’ corps also. Zankov can no longer reckon upon the devotion of Volkov, but the latter can no longer under all circumstances reckon upon the certain carrying out of his own orders. Under these circumstances the son of the Coberger Ferdinand is in a situation to pluck up his courage and to exercise his “ruling prerogatives”.

Abroad, the government of Zankov has succeeded in winning no new friends, it has even lost the sympathy of the English Conservatives.

The social basis of the white government has thus become narrower and its credit, even with the big bourgeoisie, has been shaken. The old political parties which led the struggle against Stambulisky, are almost completely in the opposition. And the groups which formally belong to the government, in secret fight against it. The military groups have similarly lost very much of their original consolidation. At present Zankov enjoys more fear than respect. His political game is played out. He will, however, not give up the power which he holds. Who will drive him out?

The “Left” legal opposition to which also the social democrats belong, represents no decisive social power. It is not in a position to mobilise a mass movement under its banner, but it still fights against the banner under which the workers and peasants are fighting to the death. It has not even the courage to demand the dissolution of parliament, for new elections under the present circumstances would bring for it a fatal defeat. Its struggle against Zankov is confined to solemn adjurations and hysterical appeals directed to Zankov. And it is quite sufficient for the latter to dangle the bogey of “Bolshevist danger” before their eyes, or to threaten them with dissolution of parliament, in order to dampen their oppositional enthusiasm. The stubbornness with which the masses fight against the white terror is without doubt the only real factor from below which will force a change in the government of the country.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. Inprecorr is an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1925/v05n70-sep-16-1925-inprecor.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1925/v05n71-sep-24-1925-inprecor.pdf