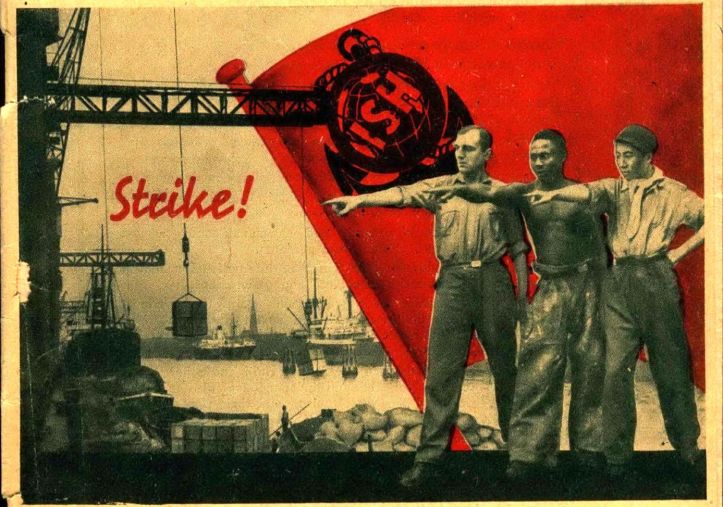

A valuable history of one pf post-war Germany’s labor highlights, the formation of the German Seaman’s Union.

‘Four Years of the German Seaman’s Union’ from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 2 No. 115. December 19, 1922.

The old trade union of the seamen, the “Seamen’s Union”, which made a bad recovery from its defeat in the conflict with shipowning capital in the year 1907, and was amalgamated in the German Union of Transport Workers a few years later, had already rendered itself practically impossible among seamen by the war policy of its leaders, headed by the well-known Paul Müller. During the war Paul Müller was an even more consistent champion of Ludendorff’s and Hindenburg’s policy than the party and trade union bureaucrats themselves in their meetings and publications, and in his writings in the “Courier”, the organ of the Transport Workers’ Union firmly supported the policy that Germany should “hold out”. When the German troops had taken Antwerp, he wrote:

“The German flag it is to be hoped waves over Antwerp, for ever!” He was richly rewarded for this later on, and even today occupies the office of seamen’s adviser in the seafarers’ guild, the shipowners institution for the protection of seamen: and the Transport Workers’ Union does not venture to dispute his position,

It is therefore quite understandable that when in November 1918 the German seamen found themselves for a moment inpossession of political power, they first called Paul Müller to account, and sought him in his office for this purpose. He, however, did not suffer anything, but only some less guilty persons and some valuable office furnishings. The seamen at this time did not allow themselves to be influenced by the outcries of one bearing sole responsibility after the war-guilty Ludendorff and Hindenburg.

But it would be an error to assume that the seamen were induced to found the international Seamen’s Union solely from motives of hate against the old leaders. As members of the Seamen’s Union they belonged to the left radical party of that time, which incorporated the idea of a united organization, and in every important political action they have boldly taken sides. As proof of this we only need to recollect the conduct of the Seamen’s Union when the social democratic minister of war Noske commanded the White Guards under Gerstenberg to march against the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils in Bremen; here the members of the Seamen’s Union were the first to hasten to the aid of their brothers in distress. Unfortunately without success.

It was not until the German revolution had been finally suppressed, after the murder of Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Leo Jogisches, and others of the best leaders of the German proletariat, that an independent organization of seamen emerged from the many petty party quarrels. In January 1919 the organization assumed the name of the German Seamen’s Union, and restricted its sphere of work purely to the economic field. It must however be taken into consideration that the surrender of the mercantile fleet, and the distress resultant on this, partially forced the members of the organization to this course. In later actions they took active part, both legally and illegally.

The “German Seamen’s Union” had been successful at that time in gathering a membership of approximately 18,000, thus practically doing away with the old association. The mighty demonstrations arranged by the Seamen’s Union at that time resulted in December 1918 in the first wage scale agreement for seamen. This scale was not however arranged by the seamen themselves, but by the associations which had meanwhile joined in a working common with the shipowners, and which were under the leadership of the Transport Workers’ Union. The terms of the agreement were as might be expected under the circumstances, but the Seamen’s Union was finally obliged to put up with it, after many protests, which however became less and less effective as a part of the sailors found occupation in undertakings at home. Apart from the decrease in tonnage of German shipping, and the resultant taking up of other professions by German seamen, the number in the Union was also diminished by the devices and machinations of the association working in community with the shipowners. Even today, although there is a precedent of a bourgeois legal verdict to the effect that it is punishable to inquire whether a man belongs to an organization or not, it is impossible for a man to find occupation in the deep-seas fishery if he is not a member of the German Transport Workers’ Union. Even to-day an agreement to this effect exists between the shipowners and the German Transport Workers’ Union. But all these measures do not bring the desired results. On the contrary, the best part of the seamen remained faithful to the organization, and not only this, in June 1919, they proceeded, to found their own publication: The Seamen’s Union. The Seamen’s Union was contributed to by the members, and speedily proved an efficient weapon in the conflict against the supporters of the shipowners and against the shipowners themselves. The Seamen’s Union was the more necessary in that the leaders of the Transport Workers’ Union did not venture to confront the members of the Seamen’s Union in public meetings, but preferred to intrigue against them secretly in their members’ meetings. It is only recently that the leader of the Transport Workers’ Union, Schumann, held the first public meeting since the war.

Without concerning themselves about petty party quarrels outside of the Union, the members sought to establish relations with other revolutionary groups. No. 4. of the Seamen’s Union is characteristic of the attitude of the Union. It contains the new program of the Union which demands, among other points, union with the miners. In accordance with this program, delegates of the Union have been sent not only once, but several times, to negotiate with them regarding coal and other questions. Very close relations were maintained with the Shop Steward movement of that time. Delegates of the Union were present at the congresses. The Seamen’s Union was naturally much influenced by the movement, and was kept supplied with material by the shop stewards’ central. Among the heads of the movement at that time could be counted Däumig, Brass, Geyer, and others, now long since landed in reformist shallows. If was only when this movement could not maintain itself that the Unionists once more stood alone.

In this situation they became engaged in a conflict with the shipowners in October 1919, and lost this after a severe struggle, in consequence of being opposed by the community workers headed by the Transport Workers’ Union. This struck a heavy blow at the organization from which it but slowly recovered. The resultant discussion on the errors committed during the struggle, above all on the failure of other workers to support the strikers by solidarity, led the organization to turn to other revolutionary groups.

Despite is the organization remained powerful enough to be able to continue publishing the Seamen’s Union. Any attempt to restore relations with the old association, in accordance with the new slogan of not destroying the trade unions, but of winning them over, would have been regarded, then as today, as an attempt at betrayal on the part of the leaders, and would have been rejected by the seamen as such. The hate against the old association knew no bounds. To this must be added that other revolutionary groups, the Unionists and Syndicalists, had supported the strikers energetically from the first day; the Bremen Syndicalists distinguished themselves particularly in this.

In Hamburg there were many consultations and common meetings among all the revolutionary groups outside of the trade unions, and these finally led to a conference, held in December 1919, at which the representatives of all revolutionary organizations were present. The Syndicalists were represented by Kater and Rocker, the Workers’ Union had as one representative comrade Appel. The Seamen’s Union was represented by comrades from every local group, amongst other by Scheel (Bremen), Rieger (Stettin), Böttcher (Hamburg). After a report by comrade Rocker, and a lengthy discussion, the Seamen’s Union decided upon affiliation with the Free Workers’ Union of Germany. This decision was facilitated by the readiness of the Union of Free Workers to grant the Seamen’s Union complete independence. An official conference of the delegates of the Seamen’s Union was held the next day, at which the result of the common conference was discussed and approved. The members’ meetings held after this also approved the decision, apart from a few contrary votes. It should be specially noted that the German Communist Party, or the communists, were themselves not quite clear on the slogan with regard to remaining in the trades unions or leaving them. But for the seamen the question was completely decided, as it is For them there was no return to the old trade union. Naturally the question was never quite disposed of, but reappeared every time a new wage agreement was brought out by the old trade union, as this latter attempted to cover its failures by lamentations over the split, and continues to do so to this day, although well aware that in actual fighting we exercise solidarity with the old union members.

The idea of the international seamen’s united organization thus took early root amongst all our comrades, and led to activity on the part of the Union not only on purely national lines, but towards the establishment of a revolutionary united front. These strivings led to the attempt at affiliation with the International Seafarers’ Federation. The attempts in this direction led to partial success. Although affiliation with the I.S.F. was rot obtained (despite the fact that many organizations belonging to the I.S.F. were in favor of it) many local groups of the Seamen’s Union gained close relations with the organizations desirous of seeing them join the I.S.F. Thus close relations were opened up with the Norwegians, Finns, Dutch, and with some groups o English. It is characteristic of the connections made with the English that a representative of the English organization, the Havelock Wilson organisation, had his headquarters in the office of the Hamburg local group of the Union, and it is merely accidental that his office is not still in the rooms of the local group. The “Dutch Federation” and the Norwegian “Seemanns Union” have lately joined these. Even during the time immediately following its establishment, the Union opened up relations with all other organisations, as for instance the Brazilian.

The endeavors towards an international united front for seafarers led to the Union sending 2 delegates to Genoa in May 1920, and though their representation did not lead to admission to the I.S.F., it was still of permanent effect on the representatives of other organizations. Lorenz from the German Transport Workers’ Union and Captain Gieseler from the Association of Captains and Officers were delegated as representatives of the German government. The declarations of our comrades were not without effect, especially on the latter. To this must be added the ever more obvious treachery of the executive committee of the seafarers’ unions in relation to the seamen who had entrusted them to represent the idea of a united organization of seafarers at Genoa.

At the same time there appeared in the organ of the association of Captains and Officers of the mercantile marine long treatises of the same import, and the relations prepared at Genoa were established with the comrades of the Seamen’s Union. After the preliminary work of both organizations had been carried out, the conference of the Association of Captains and Officers of the mercantile marine took place in Hamburg in October 1920, and approved, by 187 against 7 votes, the idea of a united organization for all persons employed in the seafaring profession, as worked out by Gieseler and his colleagues. As in the Transport Workers’ Union, every member of this organization was to be an individual member of the Union. After the conference, common consultations were held for drawing up the statutes, and a common draft was prepared and recognized by the members of the Union.

Meanwhile however, a violent opposition arose against the decision of the conference of the Association of Captains and Officers of the mercantile marine; this was carefully nurtured by all bourgeois papers, and succeeded in its aim. The Association as such did not join the united organization. Gieseler followed the logical consequences and joined the united organization with a number of his followers; of these some have again fallen away. so that it may be rightly said that the idea in itself was right, but premature. Today we know that if we had limited ourselves a that time to revolutionizing the existing committee of action of the seafarers’ unions we should have taken a step forwards in the seamen’s movement. Through this transaction the members of the Seamen’s Union have forfeited their honorable name, for the new united organization was named the “German Seafarers Union”, and the organ of the union the “Seafarers’ Watch.” The organization, on the other hand, grew from day to day, an soon attained a membership of about 10,000.

Further development has shown the Union to be correct in the opinion that its aims are better attained if as a Union, it comprises, the “lower” orders only, and not as in the contemplated united organization all persons employed in the seafaring profession, but that, as is still the case today, the mechanics, nautical technicians, and other members of seafaring branches, keep to themselves, and the whole be gathered together in one committee working against, and not with, the shipowners. The Union has already been active along these lines, and can report excellent results. For instance the latest action taken in the seafaring industry, attended which such good success. The seamen are also afforded a possibility of forming a united front with their colleagues the transport workers. The traffic union founded lately by the Transport Workers’ Union will undergo the same experience. It is impossible to imagine the traffic union otherwise than as a structure of which the seafarers, the railwaymen, and the transport workers form the triple pillars. This idea receives more and more recognition from the seafarers, and the membership of the German Seafarers’ Union increases daily. The approximate membership of the Seafarers’ Union to-day is 16,000. It should be further observed that the Union of Germain ships’ engineers and marine mechanics is already organized in the free trades unions, and gave proofs of its good will during the last wages movement.

The Unionists never really lost contact with our Russian comrades, not even at the time when they belonged to the German Free Workers’ Union (syndicalists). They have invariably appreciated the difficult position of the Russian proletariat much better than the comrades of the Free Workers’ Union, and have never concealed this fact. They have never failed to lend support, legal or illegal, when the circumstances demanded it. It is therefore only natural that the more clearly the Free Workers betrayed their antagonism to the Russian proletariat, the more the Union turned from the Free Workers. At the conference of the Union in October 1921, at which the R.I.L.U. was represented by Rusch and Farvig, and the syndicalists by Rocker, the feeling among the delegates was in favor of the former, and only a few inept remarks on Rusch’s part are to blame that the syndicalists did not receive a refusal at once.

In May of this year, at the extraordinary Union conference, the sympathy for our Russian comrades had increased to a point that conditions of affiliation with the R.I.L.U. were discussed. A committee was appointed to formulate the conditions, but this has unfortunately not yet been carried but. But if alliance of the Union with the R.I.L.U., to the great revolutionary united front, is not outwardly conspicuous, it is all the stronger internally. And the seafarers await their final affiliation at the pending congress in Moscow.

German Seafarers’ Union.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1922/v02n115-dec-19-1922-Inprecor.pdf