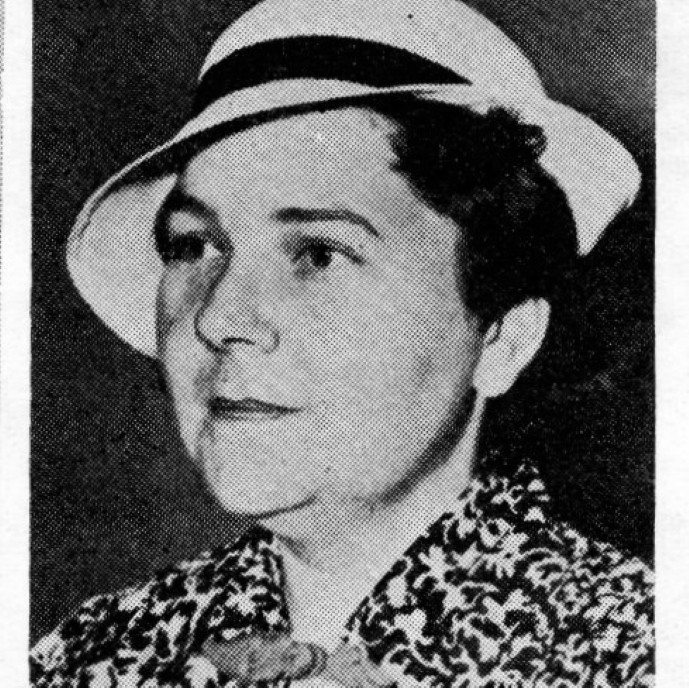

Willie Sue Blagden, a white woman, of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union is flogged by a well-dressed, unmasked gang for investigating the disappearance of Black union member Frank Weems in Earle, Arkansas. A year later Weems would emerge from hiding. His story is appended below.

‘It is True What They Say About Dixie?’ by Willie Sue Blagden from Labor Defender. Vol. 12 No. 8. August, 1936.

On June 8th, in Earle, Ark., during the strike of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, a Union meeting was broken up with the use of violence by planters and their aides. Over a dozen persons were brutally attacked. Frank Weems has not been seen by his family or his friends since his motionless body was moved from the field where the attack occurred into a nearby store. It was reported that his body had been taken to the poor farm, the following day and moved from there late that afternoon.

There are those who say that they saw Frank Weems dead. When the Union was notified that a brother had been killed in the breaking up of a Union meeting a funeral was planned. Then came the report that Weems was not dead. Before holding the funeral the Southern Tenant Farmer’s Union asked Rev. Claude Williams, Roy Morelock and myself to go over to Earle to find out if we could whether or not Weems was dead.

Let me say here, however, that funerals, or rather memorial services (particularly for Negroes), are frequently held in the south when the body of the deceased cannot be produced. It is the open secret and the open shame of the south that no investigations are made, as a rule, if a Negro is missing, and foul play is suspected. Death certificates for Negroes are easily overlooked in the Cotton Belt.

First we wanted to talk with Mrs. Weems, and Roy Morelock knew how to find out where she was living.

Rev. Williams and I were waiting for Roy when six well-dressed men drove up in a car, stopping just across from where we were parked. They walked over to us, demanded to know who we were, why we were there, whom we wanted to see, etc. Unsatisfied with our answers they ordered Williams, who was driving, to drive straight ahead, out Highway 75 until we came to a dirt turnoff over a wooden bridge that spanned a deep ravine. We turned left, and stopped out of sight of the road on the edge of a soybean field. One of the men drove ahead to a barn and came back with the piece of harness about 18 inches long, and four inches wide which was used to flog us.

There is no need of describing here the awful sense of helplessness and rage one feels in such a situation.

These men, obviously planters and their friends, searched the car for “literature” we were supposed to have brought with us. They would not believe that we had come there to find out if Frank Weems were dead. Their attitude was insulting.

After searching the car and finding only a ministers’ license, some personal papers belonging to Rev. Williams, and some material relative to the Arkansas Federation of Teachers, and the Religion and Labor Foundation which they called a “blind” the southern Gentlemen took Williams “down to the river to make him tell the truth.”

A woman has some advantages of courtesy still in the south, even in a flogging. When I refused to lie on the ground they did not force me to as they did Williams, therefore the blows lost some of their power to tear my flesh.

Believing, according to the Declaration of Independence, and the Bill of Rights that “all men are created free and equal” I could not accept the demands of this lawless gang. I was in their hands and it was evident that they had no mercy, but I would not answer some of their insulting questions. When I did answer they called me a liar.

Rev. Williams received fourteen lashes of the strap. I was dealt four.

Now Sheriff Curlin tells Governor Futrell that Frank Weems is alive. Neither the living man nor his body has been produced. Governor Futrell says, “Ninety-five per cent of what is being said through the press about the mistreatment of people in Arkansas is false propaganda…” He also says, “I predict that nothing shocking or startling will develop from the investigation now being made by the Department of Justice.”

But the Earle Enterprise, local newspaper admits in an editorial that, while there is some difference of opinion as to whether or not a woman should be whipped, since the flogging, foreign agitators are as scarce as the proverbial hen’s teeth!

The average yearly income of a sharecropper family is according to an investigation made under the direction of Dr. Wm. R. Amberson in 1934 of Memphis about $262.00. This is earned by the labor of the entire family, even the little children. And this does not represent cash in the hands of the sharecropper, it represents credit at the plantation commissary where prices are always higher than at neighboring stores, and includes an additional “carrying charges” which is supposed to be 10%, but which has been found to be in some cases 25% of the account.

The demands of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ union during the recent strike were: a ten hour day (instead of twelve to sixteen), $1.50 per day (instead of 75c) for laborers, $2.50 for truck drivers, Union agreement, no discrimination against Union members.

It is not these demands, meager as they are, that bring fear to the landlords and cause them to use violence and murder against the sharecroppers; the fact that sharecroppers, Negro and “poor white” demanded ANYTHING AT ALL is a threat to the whole feudal set up in the south.

The evasion given by the ruling class of the South is that there are also bad conditions in the rest of the country. There is still the hatred of the north, the resentment of outside interference.

But the sharecropper situation is not the concern ONLY of the south. So long as slavery exists it can reach out and effect the wages of the workers all over the country.

The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, with headquarters in Memphis, Tenn., has over 35,000 members. Of these it is estimated that about half are so impoverished that they are unable to pay any dues at all. This membership is distributed over Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Tennessee and Mississippi, and is growing.

Since the SFTU has been organized the feudal conditions on the cotton plantations have been brought to the attention of the world. But more must be done. Contributions of money and clothing are needed to provide for the evicted sharecroppers and their families. These should be sent to the office of the STFU, 2527 Broad St., Memphis.

Protests should be sent to J. Marion Futrell, Little Rock, Ark., and to Sheriff Howard Curling, Marion, Ark.

Frank Weens Alive! From Sharecropper’s Voice (S.T.F.U.). Vol. 3 No. 3. June, 1937.

UNION QUEST FOR PLANTER VICTIM ENDS

Frank Weems, Negro member of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union who has been missing for nearly a year, is alive.

This news came to the national office of the union from Chicago, Illinois, where the fifty-six year old victim of planter-terror has been in hiding for several months.

Remembering with good reason the slashing blows of the planters who drove him from his native town of Earle, Ark., a year ago, and afraid the at the long arm of planter-terror might find him out, Weems would give no indication of his whereabouts for some months. But officials of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union never gave up their search for him, and at last, by following every clue, they were able to find him.

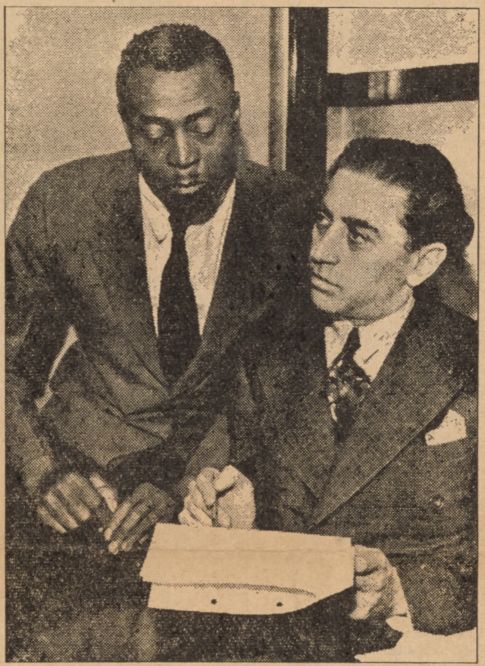

Now, his health improved and his fears quieted, Frank Weems has made known his story to Francis Heisler, Chicago lawyer for the Workers Defense League, who is planning legal action against his assailants.

A sharecropper until the bad times of 1932, then a day laborer, Weems came into the STFU in 1935. He was a member of the Earle local, in Crittenden County, one of the chief centers of actiity during the cotton choppers’ strike of May, 1936.

Pickets Beaten

On one of the early days of the strike rumors went around Earle that the planters were preparing to break up the picket line which the Earle local had planned. So Weems set out with other members of the union to New Earle to spread the warning and advise the marchers to scatter. The little company of union men and women were walking along the road when five carloads of planters drew up beside them. Many of them were carrying guns and clubs.

When they reached the group of workers the planters jumped out of their cars. One of them, Weems’ former employer, began to threaten Weems with violence claiming that Weems had not done the work for which he had been hired. Weems protested that his work had been at least worth the wages he had received for it.

But his protests turned into pleas for mercy when the group suddenly fell on him with their clubs, beating, slashing, kicking their unprotected victim. When their vicious attack had exhausted him they ordered him to leave town for good if he valued his life.

With the little strength he had left Frank Weems dragged himself into the woods to the east of Earle, There for a whole week, too exhausted to seek better shelter, he lived in hiding. Sometimes the passersby gave him food. Later he found shelter with a sharecropper near Tyronza, until he finally fled from Arkansas.

While Weems lay in hiding in the Crittenden County woods, the planters continued their reign of terror. Eliza Nolden, elderly negro woman, and Jim Reese, white sharecropper, were beaten up by the same group which had attacked Weems. The Reverend Claude Williams of Little Rock and Miss Willie Sue Blagden of Memphis, sent over by the national office of the union to investigate the widespread rumors of Weems’ death, returned to Memphis bearing the marks of planters’ clubs.

These shocking events echoed through the press of the nation. Damage suits (still pending in the federal district court) were filed by the union against the floggers of Miss Blagden, Mrs. Noldren and Mr. Reese. The sheriff of Crittenden County was called on to investigate Weems’ disappearance, but he openly refused to do so. This flagrant neglect of duty made the union and its friends throughout the country ask with even greater urgency “Where is Frank Weems?”

At last, thanks to the efforts of the officials of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, we have found the answer.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Not only were these among the most successful campaigns by Communists, they were among the most important of the period and the urgency and activity is duly reflected in its pages. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1936/v12-%5B10%5Dn08-aug-1936-orig-LD.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://californiarevealed.org/do/517546/iiif/be2e33d1-9154-4111-8c8b-f0ef388f1222/full/full/0/csfst_007184_access.pdf