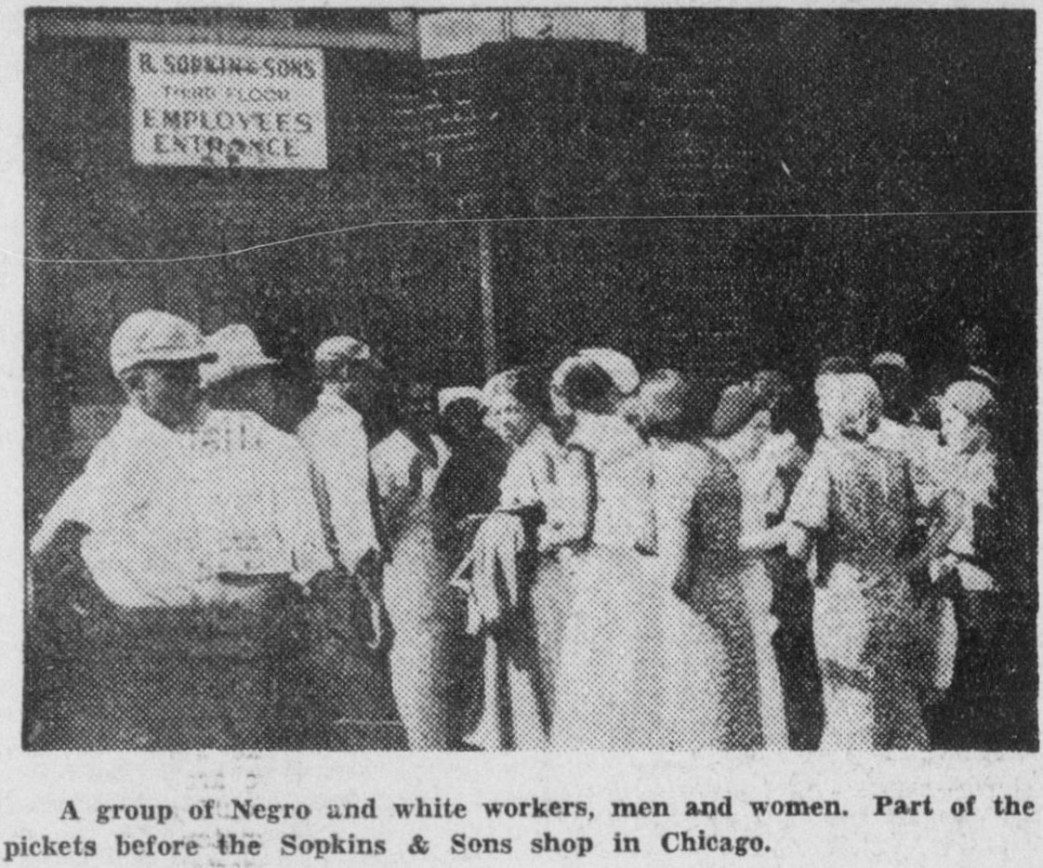

The C.P.’s District Organizer from the region on two strikes at workplaces of majority Black women, heralding a change in the labor movement. 1933’s Funsten Nut strike led by T.U.U.L.’s Food Workers’ Industrial Union was successful in St. Louis, while in Chicago the Sopkins dress shops were struck by the Needle Trades Workers Industrial Union for two weeks.

‘Negro Women in the St. Louis Strike and the Chicago Needle Trades Strike’ by Bill Gebert from The Communist. Vol. 12 No. 8. August, 1933.

THE strikes of the Negro women in St. Louis and Chicago against sweat-shop conditions are assuming a historical role in the new wave of strike struggles. These strikes are of particular importance. It is the first time in recent years that we have strikes of the Negro women, who demonstrated not only militancy and determination, but ability to organize their struggle and defeat the attempts of the American Federation of Labor and Negro reformists to wreck their strikes. At the same time these strikes are the first strikes in the recent period in the Chicago district making the Negro women the vanguard of the strike struggles.

To examine both strikes, to draw the proper lessons, it is necessary to state that the St. Louis strike has its origin back in July 8th and 11th, 1932. Then under the leadership of the Unemployed Council and the Communist Party, the unemployed workers of St. Louis forced the city administration to appropriate $6,800,000 for immediate relief; to grant relief to the demonstrators on the day of the demonstration, and to put back on the relief list 15,000 families who had been cut off. This was one of the outstanding examples of gains achieved as a result of mass action. In characterizing this victory we declared:

“July 8th and 11th will go down in the history of the working class in St. Louis as the beginning of a mass movement of the Negro and white workers,”

and further, that the immediate task confronting the Communist Party of St. Louis was:

“to consolidate the movement of the unemployed by building block-committees, penetrating local unions of the A. F. of L., reaching workers in the factories, and uniting with them in a common struggle against wage cuts and unemployment.”

As a result of the successful struggle of the unemployed, and drawing in new forces from the masses into the Party, profound changes have been made in the leadership of the Party in St. Louis. The whole leadership, consisting of some small businessmen and elements that have no contact with the broad masses, has been eliminated and workers who showed their ability to organize and lead mass struggles were elected to the section leadership. It is precisely because of these changes that it was possible to orientate the Party membership and the work of the whole Party toward the shops. This orientation, however, is not yet to the big shops.

A Negro Party member, who just a couple of months ago came into the Party, through the Unemployed Council, established contacts with a group of Negro women working in the nut factory and immediately brought the conditions of the workers in the factory to the attention of the Party Section Committee. The section organizer of the Party personally took charge of the preparation for the strike. Already at the first meeting with a few women from the shop the objective was set to work toward the development of a strike for increase in wages, for equal wages for Negro and white women and recognition of the Food Workers Industrial Union, affiliated with the Trade Union Unity League. Committees of the workers, working women, were set up with the objective to spread agitation for a strike from department to department. After approximately six weeks of systematic preparation for a strike, when the initiative group for the strike reached the number of sixty, the women decided to declare a strike.

It is very important to note that the women in the shops were religious and had no experience in the working class movement. When they decided to strike and when the vote for strike was taken, one of the leading Negro women called upon the rest of the women to join in prayer, saying: “Oh Lord, give us strength to win our demands. Boss Funston does not treat us Negro women right. We made the first step, oh Lord, you should make the second step and help us to win the strike.”

The Party Committee very correctly proceeded toward organizing the strike. The workers themselves elected the strike committees. The Party comrades impressing the workers that the problem of the strike and the victory of the strike was their own problem, at the same time giving them guidance and leadership on every step before, during and after the strike.

The strike began in one of the factories belonging to the R.E. Funsten Company, the largest nut factory in St. Louis. The weekly wages were from $1.30 to $2.95. In other companies the wages were even below that. During the strike, I saw the envelopes of the girls working in the Central Pecan and Mercantile Company where they were receiving their weekly pay, sometimes as low as 70 cents, $1.14 and $1.26 a week. The white girls in all the shops who were in a small minority were receiving from 30 to 40 percent more than the Negro girls. This was done for a definite reason—to prevent the unity of the Negro and white girls. Negro girls were abused by the bosses; conditions in the shops were unsanitary; many of those who were working in the shops, slaving for 54 hours a week, were forced to apply to the Providence Association for additional relief. It was reported by the workers that approximately one-third of the workers in the nut factories were on relief lists. These conditions among the Negro women in St. Louis have existed for years. The Urban League and all other Negro organizations never paid any attention to this miserable indescribable slavery of the Negro women in the city of St. Louis.

When the strike was declared in one shop of the Funsten Company the workers immediately decided to spread the strike to three other shops belonging to the same company. The next day those other shops came out on strike. There were difficulties in convincing some of the white women to come out on strike. However, very few attempted to go back to work. In every shop a strike committee was immediately set up, elected by the strikers themselves and then the General Strike Committee was elected in the same manner. At the meeting of the General Strike Committee, decisions were made to spread the strike to all nut factories in St. Louis; to one shop every day.

The methods by which they proceeded to do so were as follows: A committee of 15 or 20 strikers with their banners and leaflets would appear before the shop at the time when the workers were leaving and agitate and propagate among them to join in the strike, popularizing the demands of the strike which were: 100 per cent increase in wages, recognition of the union, equal wages for the Negro and white girls, sanitary working conditions, and other demands. These demands were formulated by the strikers themselves with our guidance. As usual, they would meet with response from the workers. Meetings would be held some evening with the workers from the new shops, and in the morning, mass pickets before the shop. In practically all the cases where correct preparations were made, the workers responded 100 percent to the strike call. In the course of eight days, twelve shops were on strike, the number of strikers reaching 1,800, of whom 85 percent were Negro women.

The strikers not only developed day to day activities in front of the shops, in the form of mass picketing, which was in many cases a little neighborhood demonstration because the Negro women brought with them their husbands, brothers, their friends and neighbors, and because of the active mobilization of the workers by the Party and Unemployed Council. The strikers also raised the whole problem of the strike to a broader plane by involving other workers into active participation in the strike, by visiting trade unions, fraternal organizations and churches for support; by staging parades and demonstrations in front of the City Hall, demanding the withdrawal of the police and the release of the arrested pickets, the stopping of police brutality, etc. In short, the strikers surrounded themselves with thousands of workers, employed and unemployed, Negro and white, who supported them; as a result it was impossible for the city government to defeat the strike.

The attempts of the bosses to raise the “red scare” as a means of splitting the ranks, did not become a problem in this strike, only because the Party was brought forward in the strike. At the first mass meeting of the strikers, the representative of the Party, a comrade who actively participated in the preparations of the strike and in the course of the strike, explained the role of the Communist Party. He was greeted by the strikers and the Communist Party won their complete confidence. It is sufficient to mention one incident to point out to what extent the strikers were ready to defend the Party. A committee of the strikers was elected to meet with the Mayor’s committee, which consisted of representatives of the City, some Negro reformists and the boss, where an agreement was to be reached. Mayor Dickman demanded that the union organizer should not be seated at the meeting because he is a Communist. The strikers’ committee, however, refused to meet with the Mayor’s committee unless the representatives of the union were seated. When the spokesman for the strikers was asked: “Why do you stick to the Communist Party?” her answer was: “The Urban League never sticked with us, nor the Universal Negro Improvement Association nor any other Negro organization or church. The Communist Party is the only one that give us guidance and leadership. That’s why we stick by the Communist Party.” The union organizer was seated.

In the course of the strike the union was built on the basis of the shop. Shop locals of the Food Workers Industrial Union, affiliated with the T.U.U.L., were established in every shop on strike, embracing practically all strikers. It was necessary to readjust dues in such a manner so that the strikers would be able to pay. Therefore, initiations were reduced to 10c and dues to 10c a week. The Communist Party and the Young Communist League were also built during the strike. At present, there are six shop units of the Party and four shop units of the Young Communist League that have been organized, and the further consolidation of the Party is proceeding. The strikers won all their demands: Increase of wages by 100 per cent; equal wages for Negro and white, improvement of the conditions in the shops, and recognition of the shop committees and the union.

The victory of the St. Louis strike is of tremendous importance from the point of view that the strike was organized and led by Negro women. They joined the union and large numbers of Negro and white women strikers joined the Communist Party and Young Communist League. What a change took place among these women who practically without exception were religious, during the eight days of the strike! This Negro woman, who at the first meeting where they decided to strike, prayed to the lord to win the strike, afterward, when the pastor in the church refused to take a collection for the strikers, came back to the strikers and reported that from now on the union is her church and now she is a member of the Communist Party.

Many comrades, isolated from the masses, who are afraid to develop struggles because there would be no leadership, ought to have been on the picket lines and at the meetings of the strikers, heard these Negro women, their speeches, and seen them in action. One would have thought that these Negro women had been for years trained in the working class movement. Every one of them very quickly adjusted herself to the situation and gave leadership. There were no difficulties with the strikers in understanding the full nature of the strike. Best proof of this is that the strikers were not fooled by Mayor Dickman’s demagogy, in coming to speak in the Communist Party headquarters, which were the headquarters of the strikers; nor the more skillful of the Negro politicians, Grant, who opened his speech by giving credit “to the Communist friends for bringing to the attention of the city the miserable conditions of his people.” None could be shaken from the belief that the Communist Party was their Party, that their protection was the Food Workers Industrial Union.

The Party participated very actively in the strike. But not only that. It broadened the outlook of the strikers. At the mass meetings, we discussed with the strikers the Scottsboro boys’ case, the national policy of the Soviet Union, comparing it with Negro oppression in the United States, comparing the Soviet Union with the United States as the country where there is no unemployment, where the workers enjoy conditions, etc., showing the revolutionary way out of the economic crisis of capitalism.

When the strike ended and the workers went back to work, there was no decline in the activities of the union. On the contrary, the activities of the union and of its members have been increased. In their respective shops, workers of the shop committees are actively defending their interests and gaining small concessions from the bosses, in addition to the victories obtained in the strike. These nut pickers furthermore decided that their task is to organize the workers in other industries. They decided that every shop should concentrate upon and organize other shops: needle, railroad, etc.

As a result of these activities, strikes took place in two needle trades shops, both resulting in victory. A union has been organized and two shop units of the Party formed and one shop unit of the Y.C.L. At present there is a strike of 300 textile workers in three shops as a result of the organizational work of the nut pickers. One of the nut pickers developed work among the marine workers, others also have established contact with and recruited railroad workers to the Party.

As a result of the victory of the nut pickers’ strike, the popular slogan among the workers, employed and unemployed, is: “Do as the nut pickers did” So much so that in many shops workers are discussing the results of the strike, preparing their own strikes, building groups in the shops, organizing unions and building the Party.

The successful strike also had its effect upon the workers who are organized in the American Federation of Labor. At the convention of the Missouri State Federation of Labor, at which the Party had no contact whatsoever, rank and file delegates raised the question of the nut pickers’ strike, demanding that the A.F. of L. change its policy of conducting strike struggles and adopt the policy developed by the nut pickers. The bourgeois press was so alarmed by the sympathy shown by the rank and file delegates at the State Convention, that they spoke of a “split” in the A.F. of L.

The St. Louis Party organization, as a result of the strike activities, changed its outlook and realized that the main problem confronting it is penetrating into the big shops of the heavy industries, seeing the strikes in the light industries as the stepping stones to the steel mills, railroads and packing houses, toward which the whole attention of the Party must be directed.

By registering the above, it is necessary to state that further consolidation of the union and the Party in the nut factories in St. Louis is necessary so that the union and the Party can systematically develop struggle for the improvement of the conditions in the shops (wages, hours, etc.), and systematically carry on a campaign against the Negro reformists, the American Federation of Labor, and the left reformists, the Muste types. Under no circumstances must we already feel that all the workers in the nut factories have been won ideologically to the extent that no further work is necessary. On the contrary. It is necessary to carry on systematic political work among the workers in the nut factories bringing in all other problems confronting the working class

***

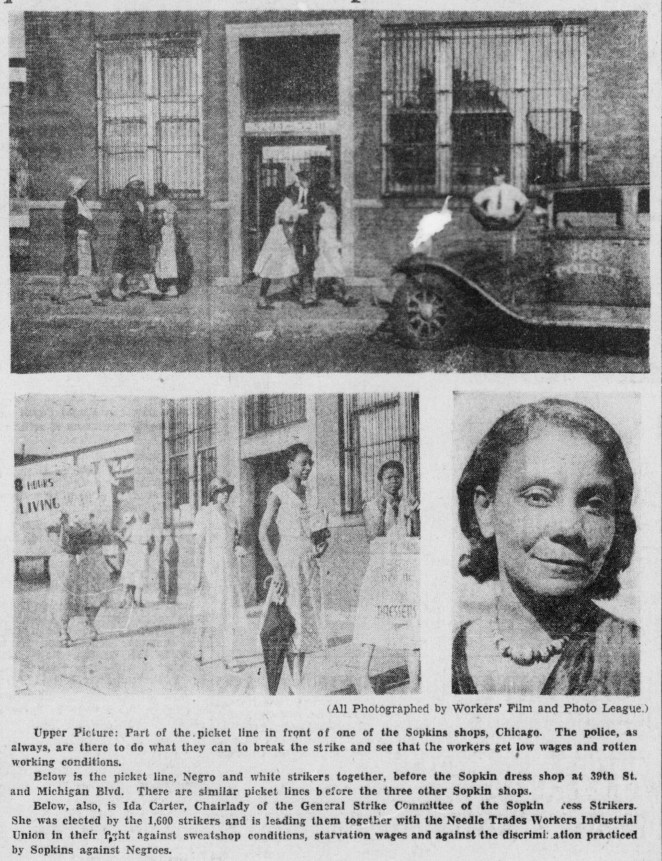

The Sopkins dress shops in Chicago employ approximately 1600 workers, primarily Negro women, who work under similar conditions to those in the nut factories in St. Louis. Here the Section Committee of Section Seven, with the Needle Trades Workers Industrial Union, undertook the task to penetrate the shops, with the objective to develop immediate strike struggle. Contacts were established with the workers through the Party member working in the shop. Meetings were held, committees set up, the whole preparation was made in a hurry because the season in this industry was reaching its peak and if the strike were delayed, it would be difficult to carry it through. The District Committee together with the Section Committee carefully analyzed the situation and time of the preparation for a strike. Here, too, concentration was made on a strategic shop on 39th and Michigan Avenue. To close down this shop meant crippled production in other shops.

At a mass meeting, at which over 200 were present, the workers of the Sopkins Dress shop unanimously decided to declare a strike, formulate demands, elect a strike committee, draw the union organizer into the committee, etc. The first day the shop was out, only a handful remained on the job. The strike spread immediately to three other shops so that every shop of Sopkins dress was on strike. Mass picketing was developed and also night picketing because of the announcement that Sopkins would recruit workers for a night shift. All the attempts to bring strikebreakers into the shops were defeated by mass picketing. Police were mobilized in large numbers and picket lines were constantly attacked and smashed to the point that around 39th and Michigan no pickets were permitted. But even this terror did not break the ranks of the strikers. Daily meetings of the strikers took place.

However, in the course of the strike, there were some glaring weaknesses. For instance, no shop locals of the Needle Trades Workers Industrial Union were organized during the course of the strike. A General Strike Committee was elected by the strikers and actually was the leadership of the strike, but in the respective shops no strike committees were set up. This weakened the strike and made difficult daily mobilization of all the strikers, only about one third actively participating in the strike.

The Party was not brought to the forefront during the strike among the strikers. There was a tendency among some leading comrades not to bring the Party forward in an attempt to avoid the “red scare” issue. This was at a time when the Negro press raised the cry that “Reds declare a strike and actively campaign against white workers participating in the strike” for the purpose of weakening and defeating the strike. The A.F. of L. came to the strike and attempted to divide the workers. The A.F. of L. under police protection came on the picket line, and a couple of A.F. of L. organizers distributed their literature. This antagonized the workers against the A.F. of L. leadership.

The Negro reformists and misleaders, particularly Negro Congressman De Priest, actively attempted to smash the strike. De Priest called a meeting of the strikers. The Strike Committee decided to mobilize all the strikers to attend the meeting with the object of taking the meeting over. The strikers took over the meeting, elected their own chairman and when this was done, by a unanimous decision of the strikers, representatives of the Needle Trades Workers Industrial Union and the Trade Union Unity League, James Ford, E.B. Girsch, came to the meeting, and were greeted enthusiastically by all the workers. In the face of De Priest, Sopkins and the Negro politicians who were present at this meeting, the strikers rejected the proposals for settlement of the strike offered by De Priest, which provided for the setting up of a committee of “workers, bosses, and citizens to adjust the grievances of the workers in the shops.” The workers demanded recognition of their Union and shop committees and refused to have any committee of the bosses.

But De Priest did not end his treacherous role when he was defeated at the meeting of the strikers. On the day when the agreement was to be signed between the representatives of the Union, the strikers and Sopkins, including 17 1/2 per cent increase in wages, recognition of the shop committees elected by the workers in each shop and department, improvement of the working conditions in the shops, etc., Congressman De Priest demanded that Sopkins refuse to sign the agreement which he previously agreed to, which included recognition of the shop committees. De Priest fully understands the meaning of the shop committees and was therefore against it. Sopkins had the support of De Priest and therefore refused to sign the very agreement he had agreed to sign previously. This was a crucial moment in the life of the strike. There were tendencies among some leading comrades to reject the whole agreement and continue to strike. It would have meant the smashing of the strike and defeat, because as yet the strike was not organizationally consolidated. The union was not well established, the Party did not play a sufficient role in the strike. This leftist approach would have been very disastrous in the strike. It was only under the guidance of the District Committee that the following decisions were reached:

1. We accept the part of the agreement which provides for a 17 1/2 per cent increase in wages, and improvement of conditions.

2. That we reject the part of the agreement that provides for setting up of committee consisting of one worker of the shop and social worker, and in case they don’t agree on the problems confronting the workers, they will be turned over for settlement to the representatives of the bourgeois “Citizen’s Committee.”

3. That we elect in every shop at special meetings of the strikers a shop committee which will take up the grievances of the workers, being backed up by the workers to carry the struggle for the improvement of the conditions of the workers inside the shop.

These proposals were made to the strikers, they were unanimously accepted, striker after striker made a speech, characterizing the treacherous role of betrayal of De Priest, stating that they are returning to work not defeated, but with important victories and above all, with organization. Shop meetings in every shop were held, shop committees elected and the union consolidated organizationally. Approximately two-thirds of the strikers joined the union, The correctness of this policy has been proven in life itself. Not only did the workers receive a 17 1/2 per cent wage increase, but in many cases shop committees were able, with the mass support and pressure of the workers, to force the boss to grant more. In many instances the increase represents 30 to 40 per cent. The shop committees, though officially not recognized by the company, are actually a tremendous weapon in the struggle for better conditions.

The strike in Sopkins Dress Co. lasted two weeks. The ending of the strike in due time was a correct step. If the strike had been prolonged, under the conditions that we were faced with, this strike would have been lost for the workers and no organizational consolidation would have been achieved. The outstanding weakness in the Sopkins Dress strike is that the Party and Young Communist League were not built sufficiently. Only a handful of workers were recruited into the Party and Y.C.L. and only one shop nucleus of the Young Communist League has been organized so far. This in spite of the fact that large numbers of Negro women are ready for the Party and 30 filled out application cards.

The Party was not built primarily because many leading comrades active in the strike grossly underestimated the need of building the Party in the course of the struggle. The task confronting the Party and the union is to consolidate organizationally in the shops, by building shop locals of the Needle Trades Workers Industrial Union; by building shop nuclei of the Communist Party and Young Communist League. Further, to utilize this strike to establish contacts with new sections of the workers, to penetrate into every shop and above all into the stock yards.

Further, it is of tremendous importance to concentrate our attack on the betrayal of the Negro masses by Congressman Oscar De Priest, whose role is that of an arch enemy of the Negro people and lackey of the white ruling class. De Priest was behind the killing of three Negro workers on the south side of Chicago in the eviction struggles during the August days of 1931. De Priest is behind the terror that rages against the Negro masses on the south side of Chicago and now he openly robbed the Negro women of their victories in the Sopkins Dress. By concentrating the main attack against De Priest and his associates, we must not overlook that the A.F. of L., who Jim Crows the Negro workers with high dues, prevents workers in the sweat shops and other industries from joining the unions and wherever there are strikes, they come in at the call of the bosses for the purpose of dividing the workers and smashing the struggle. An example of this we have seen in the spontaneous strike of 50 packing house workers at the Oppenheimer Company. These workers struck spontaneously. The Packing House Workers Industrial Union immediately established contact with the strikers and they accepted the leadership of the Union, But the. boss brought in the A.F. of L., succeeded in winning over some white workers, resulting in the defeat of the strike.

In every strike struggle, in every preparation for a strike, in addition to the correct application of the policy of strike strategy and of proper organization, it is necessary to concentrate the main strategic attack upon the leaders of the American Federation of Labor and “left” reformists of the Muste type, and in a completely convincing manner, expose their role of betrayal. Without defeating the influence of the leadership of the A.F. of L. and Musteites it is impossible to speak of successful strikes.

The strikes of the Negro women in St. Louis and Chicago helped the Chicago Party district organization in orientating the Party toward the work in the shops and conclusively proved the possibilities of development of strikes. In light of the Open Letter, the task confronting the Chicago Party district is to penetrate into the big shops, the steel mills, mines, railroads and packing houses, to make these shops a fortress of our movement.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This Communist was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v12n08-aug-1933-communist.pdf