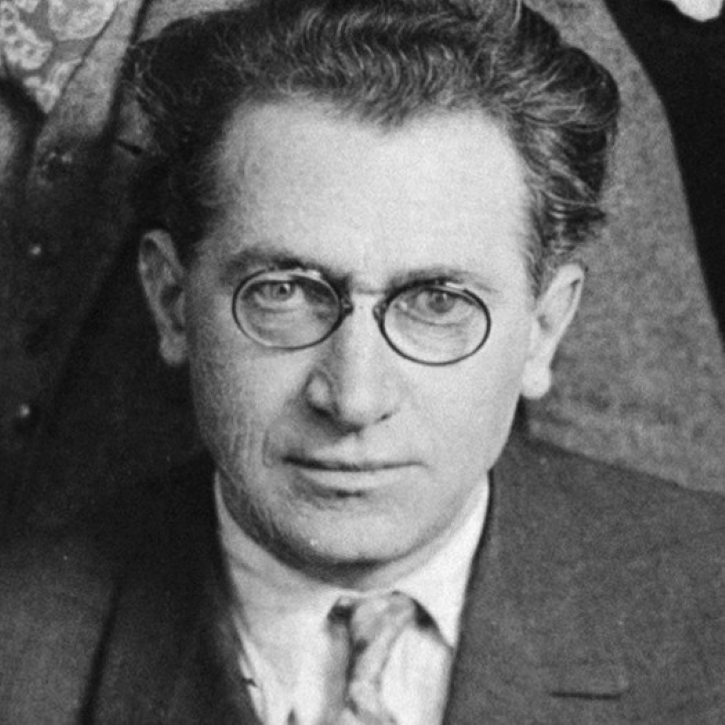

Olgin, himself a veteran of Russia’s revolutions, writes on the world-historic, earth-shaking events opened in 1917 as seen in five practical manifestations. Born in Ukraine in 1878 where he joined the revolutionary movement as a member of the Bund, becoming editor of its paper, member of its Central Committee, and author of almost all of its proclamations during the ‘1905.’ Active in Kiev and Vilnius, he also organized Jewish self-defense groups against the pogromist reaction. After the Revolution he would study in Germany, where he was stranded by the outbreak of World War One, eventually making his way to New York in 1915 where he wrote for Forverts and became a Left Wing leader of the Socialist Party’s Jewish Socialist Federation. Like many in the JSF, Olgin sided with the Workers Council group and stayed in the SP to fight for its adherence to the Third International until 1921 when they left to help found the new Workers Party, the real founding of a united Communist Party in the U.S., in December, 1921. A prolific writer, mainly in his native Yiddish, and capable of brilliance, this article is from a series written for Forward during and after his six-month tour of Soviet Russia at the end of the Civil War. Shortly, Olgin would start the Communist Party’s Yiddish-language daily, Morgen Freiheit, which he continued to edit for the rest of his life.

‘What the Revolution in Russia Has Accomplished’ by Moissaye J. Olgin from The Toiler. No. 174. June 4, 1921.

An Answer to Those Critics Who Do Not Understand the Vast Historical Significance of That Revolution.

At this stage let us see what the Russian Revolution has accomplished in its first three years. We know it has destroyed much. It has driven out the big landowners and abolished that class. It has driven the manufacturers from their factories and deprived them of their capital. It has taken houses from the rich who owned them; there is no longer any private ownership of houses. It has declared the earth, the woods, the workshops, the factories, the coal mines, the oil wells, the railroads, the steamboats and the houses, the property of all the people. It has abolished all titles, privileges, class rule, private enterprise and profits. It has declared the right of every man to work and the duty of the government to supply everyone, with a living.

All this was easy. In a time of revolution it is easy to destroy. There is no need of any great genius, any well thought out plan, for that. The breaking up goes on because the people are stirred up. Destruction goes on because for far too long the people have suffered. In the dust and smoke and blaze of battle, age-old structures are shattered. And, when everything old around us is broken up, scattered and destroyed, the victors announce that it is the beginning of a new world, a new era.

But it is not so easy to build as to destroy. For that is needed knowledge, understanding. Earnest labor is necessary. A plan is necessary. People drunk with joy will not accomplish much. Fine talk is not enough. The holiday mood and holiday clothes must go, for there is work to be done, the handling of the lime, the bricks, the iron and the stone for the new structure. Those who have a plan must work together and encourage each other in the stupendous task. Great patience is needed. Difficulties will be met with and they must be overcome. Though the walls are bare and the roof unfinished in the new structure, future beauty must be visualized.

Russia’s Accomplishments.

Has the Russian Revolution truly begun the building of the new world? Thousands of people do not think so. Thousands of people believe that things are worse now than ever before. Everything, they say, has been destroyed, nothing built up. The Russian Revolution was pushed into a corner, they say, and there is no way out.

Is it really so?

It is hard for a man to grasp a world-historic occurrence. Only when we are several years removed from it do we begin to understand the greatness of it; only when its effect is noticeable everywhere do we realize that it was something of world-historic moment. In the time when it takes place we see only a part of it; sometimes only the fringe of it. And everyone thinks only of the small part which he sees.

Many an honest man reached a wrong conclusion in the Russian Revolution. If one goes to Russia and has dealings with dishonest communists, the revolution appears as the rule of thieves. If another goes to Russia and sees that there is not enough to eat, the revolution to that one becomes the rule of hunger. If a third one sees that the minority parties have no right to issue their newspapers, he decries the revolution as a tyranny. If a fourth happens to have a relative there who was placed under arrest by the extraordinary commission which has charge of counter-revolutionary activities, the revolution to him becomes a universal spy system. And everyone thinks that he saw the revolution and that he appraised it according to its worth. But each has failed to see the revolution in its entirety as an occurrence of world historic import.

But the Russian Revolution has already lasted long enough to permit us to view it as a whole. It has already acquired a distinct form so that we may draw conclusions from the first period of its history. What has the Russian Revolution accomplished in these few years?

(1) It has given ever all the factories, mines and other industrial establishments into the hands of the state, and organized a central apparatus for taking care of the economic life of the country. It has proven that this is possible, in spite of the contentions of the learned and practical men of the times that it is impossible. It has proven that a people can take into its own hands. all the productive forces and use them for its own good, ruling over these forces according to its own will.

No one says that the economic apparatus of Russia is working very smoothly. None of the Russian leaders is pleased with the economic arrangement of the soviets. There is bureaucracy. There is too much red tape and too little work done. Everything works slowly, where it should work as a well-oiled machine. Here and there the machine becomes altogether clogged up, and it takes time to get it working again. Now one part breaks down, then another. There is cause for grief and maybe for anger.

But the leaders in this Herculean struggle are not discouraged. They know that it could not have been otherwise. A new class has acquired power. It lacks knowledge. It lacks experience. The old intelligentsia has sabotaged the new system and its ideals. The new intelligentsia is not yet ready. The country was worn out even before the revolution; the economic body was debilitated long before the working class took everything into its own hands.

It is almost seven years since the beginning of the war. During this time there was no possibility of maintaining the nation’s means of production, no possibility of making necessary repairs and renewals. The machines were old and worn out; the locomotives damaged, the rolling stock deteriorated; many of the materials needed for repairs were lacking altogether, and for many materials substitutes of a much lower grade and quality had to be used. When we keep in mind that the management of the factories is not of the best and that the workers are not yet everywhere used to the new order, how can we hope to find everything running smoothly?

Yet it remains a fact that the apparatus is here, that it works, that it is constantly improving, that the productivity of labor increases and that the country can do very well without private enterprise. Even the most rabid opponents of the present order, the Mensheviks and social revolutionists, do not say that the factories ought to be returned to their previous owners, The Russian Revolution has taught even them that the country can do very well without that celebrated “private initiative.”

(2) The Russian Revolution has created a tremendous apparatus of distribution. This is altogether new in the history of mankind. The state took it upon itself to see to it that every citizen is provided with food, clothing, shelter and fuel. This is in order that some may not have too much and others not enough. The apparatus of distribution takes from the village the products of the soil and from the city the products of the factories and divides these among the people according to a specific plan. And the people consist of one hundred and twenty million souls. The people everywhere, from Archangel to Odessa, from Minsk to Jakutsk, turn to the apparatus of distribution and rely upon it to supply them with the means of livelihood.

Here too not everything runs as smoothly as it should. The most essential products are lacking. It is difficult to get a little food, the simplest tools, or clothes. Nor is the law of equality always observed. There are some who, in spite of everything, do receive more than their fellowmen, while again there are others who suffer terribly. This is so because, first of all, there are not enough products to go round; and secondly, the apparatus of distribution is entirely new, there has not been time enough for it to be perfected as a result of practical experience. Nevertheless this apparatus works energetically and successfully. It has spread over all that vast revolutionary country, it has reached every village, every town, every shop. The apparatus of distribution is considered one of the most important institutions in Russia today. It is the opinion of all, even of its enemies, that this apparatus works now much better than it did a year or two ago. It is adjusting itself, becoming finer, more complicated. It now takes into consideration particular condition of particular provinces, cities or individuals. As soon as there is more wheat, more corn, more meat, more butter, more iron, more wool, more coal, more tools, more paper–the apparatus will work much better, the present shortcomings will disappear and the people will have little reason to complain.

Let us reiterate: the whole machinery is new. It began to function some three years ago. It had to do its work in a time of great suffering, in a time of insurrections and counter-revolution within the country, a time of wars with both internal and external enemies. And yet Russia has convincingly proven that a country can do very well without private trades, without merchants, storekeepers and speculators of every kind. The law is now permitting the peasant to sell his product in the free market to private people, but it does not permit the existence of the trader, the middleman.

(3) The revolution has established the general law, that he who does not work, neither shall he eat. This is not a law only on paper, it is a law practiced in everyday life. There must not be found citizens in Russia who do nothing. Everyone must do some kind of useful work, physical or mental. Ordinarily everyone selects his or her work according to his or her knowledge, experience and inclinations; to be sure, with the consent of the state. Sometimes, though, the state directs the work of one kind or another when the state thinks that necessary.

This, people say, is against human freedom. But this freedom does not mean that one should have the right to go about doing nothing useful and living on what others produce. Sure enough, it would have been much better if people attended to the work to be done willingly, without having to be forced to it. But people do not become transformed within two or three years, and the new society must go on functioning. Therefore the state compels the people to serve society, which ultimately improves the life of everyone of the people.

It is natural to find there cheating, laziness, incompetency and crime. Not so quickly does the spirit of a community change. There are groups of people that will never serve honestly the new regime–these are the exploiters, those who never worked, and the spendthrifts of the past. There are groups that only after much pain and trouble may begin to see that to serve the new society is an honor and not a misfortune, even though they are not to be the leading spirits in this new society these are the intelligentsia. There are people, and many of them, who will under cover of their social position carry on some dirty practice. This is harmful and is being fought against, but it is not a matter of vital importance. As soon as things improve, these dirty practices will disappear. The main thing is that for the first time there is established a society where everyone has to do some useful work, and that in a country of one hundred and twenty million people.

(4) The revolution has created a new system of jurisprudence and administration. I have already written about the system of the Soviets. I shall surely write more about that in the future. About one thing there is no doubt, and that is that the Soviet regime has no equal in the history of mankind, and that it is now a securely established institution all over that vast country. It should not be forgotten that this tremendous administrating apparatus is an entirely new institution; there is not a single governmental office left from before October 1917. The revolution has wiped out all the old system of administration, the old system of laws and the old system of administering justice, and in its established the system of soviets, which work indefatigably, develop and grow.

(5) The revolution has created a new army with a new psychology and a new social ideal. And all this in three years, no more. In this time they had to face Brest-Litovsk, the German invasion of Russia, the Czecho-Slovaks, Kolchak, Denikin, Judenitch, the Japanese and English in Siberia, the English and Americans in Archangel, Peltura, the Esthonians, the Poles, Wrangel and Kronstadt. They had to face counter-revolution, insurrection and animosity within the country. They had to face sabotage and all kinds of trouble from the intelligentsia. They had to face hunger and need. They had to face inexperience. And yet they have created much, so powerfully created. This was possible because of a great revolution, because of a great, new social force.

And people complain that the revolution has failed. As though the revolution could fail, even if it should happen that tomorrow some general should ascend the throne for a month or two.

Poor, blind critics! They are to be pitied. They cannot see the light of history.

(Translated by S. SMITH From the Jewish Daily Forwards, New York.)

The Toiler was a significant regional, later national, newspaper of the early Communist movement published weekly between 1919 and 1921. It grew out of the Socialist Party’s ‘The Ohio Socialist’, leading paper of the Party’s left wing and northern Ohio’s militant IWW base and became the national voice of the forces that would become The Communist Labor Party. The Toiler was first published in Cleveland, Ohio, its volume number continuing on from The Ohio Socialist, in the fall of 1919 as the paper of the Communist Labor Party of Ohio. The Toiler moved to New York City in early 1920 and with its union focus served as the labor paper of the CLP and the legal Workers Party of America. Editors included Elmer Allison and James P Cannon. The original English language and/or US publication of key texts of the international revolutionary movement are prominent features of the Toiler. In January 1922, The Toiler merged with The Workers Council to form The Worker, becoming the Communist Party’s main paper continuing as The Daily Worker in January, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/thetoiler/n174-jun-04-1921-Toil-nyplmf.pdf