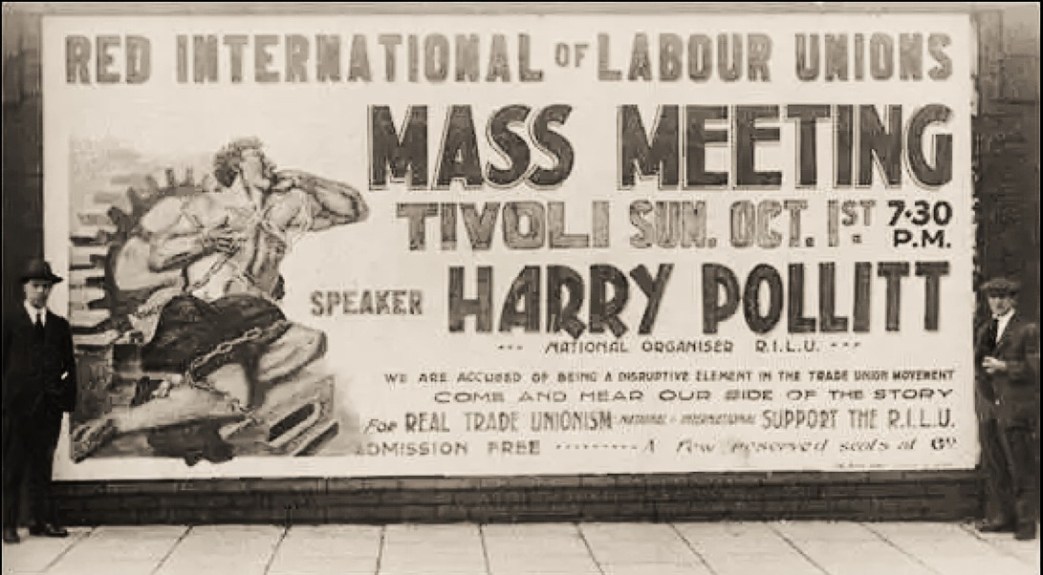

Ashleigh gives us valuable background to the developments of what would soon become National Minority Movement, convening its inaugural gathering in August, 1924 representing around 200,000 workers, and affiliating to the Profintern with its first General Secretary the veteran Tom Mann.

‘The Minority in the British Trade Unions’ by Charles Ashleigh from The Daily Worker. Vol. 2 No. 10. March 28, 1924.

THE last few weeks have witnessed a definite and encouraging revival of the left-wing spirit among the rank and file of the British labor unions. It will need all of the best tactical and organizational efforts of the British militants to give this new spirit a direction, a crystallization, so that it does not uselessly expend itself, and thus leave the movement where it was before.

There have been attempts before at the organization of a minority movement in the British labor unions. For some years, there existed various local organizations, Industrial Leagues, etc., which drew, in great measure, their inspiration from the industrial unionist propaganda in America. Members of the British Socialist-Labor Party played a considerable part in these early organizations. They did not, however, share the dualist conceptions which prevailed, at that time, in the United States, and sought to bring about industrial unionism through educational and agitational work within the existing unions.

Syndicalist Agitation.

Then, with the return of Tom Mann to Britain, there came a development of Syndicalist agitation. A number of militants were grouped around Tom Mann, and the “Industrial Syndicalist,” was published as their organ. These British Syndicalists owed far less to the Anarchist tradition, however, than did their conferes in the Latin countries. Their point of view was strongly Marxian, although their position regarding parliamentarianism was that of our Anarcho-Syndicalist friends. It was before the Russian revolution, when the revolutionary conception of the nature and historical functions of the capitalist state had not clarified in such marked degree as it later did, thru the clear and scientific teaching of Lenin.

Still later, during the war, there came the Shop-Stewards’ Movement, the first real attempt to create, on a national scale, a left-wing industrial movement. This was in the time of the shop committees, the period of the heroic struggles of the workers of the Clyde, led by their shop stewards. This movement, however, laid special emphasis on the creation of shop committees, at the expense of the other necessary tactics—the penetration of the trade unions, the conversion of the Trades Councils into organs of militant action. For this reason, partly, and also probably because of the great slump after the war, the shop committee movement lapsed.

The Red International.

And then, for a long dreary time, during which the offensive of capital had its own predatory way with wages, hours and shop conditions, and the unions lost hundreds of thousands of members, there were but sporadic, scattered attempts at the building-up of a real nation-wide movement within the trade unions.

Nevertheless, preparations were being made. The Communist Party of Great Britain had come into being, with its definite policy of trade unions work, along the lines laid down by the International. A British Bureau of the Red International of Labor Unions had been established in the United Kingdom. And slowly the forces of the left began to reassemble.

The problem in Great Britain is somewhat similar to that in America. The British workers have been isolated from the currents of European Socialism. Their economic position, for years, was better than that of the workers of all other great European powers. The colonial empire of Britain enabled certain sections of the British proletariat to be maintained by the employers in comparative comfort—at the expense of the toiling millions of India, Egypt and other lands. The workers’ leaders, therefore, and wide strata of the workers themselves, were saturated in the ideology of the small bourgeoisie. It has required the disconcerting suddenness of the reduction of their standard of living, since the war, to bring them to some realization of the necessity of vital changes in trade union structure and tactics. Now, however, the soil is prepared; the objective conditions for the revolutionizing of the British trade union movement are present. What is now needed is the perfection of the mechanism by which the revolutionists may take advantage of these conditions.

The Gigantic Task.

And, slowly, this mechanism appears to be evolving. It is slow work, and all due account must be taken of the special traditions and psychology of the British organized, workers. The launching of furidly worded manifestoes, the calling of enthusiastic conferences—at which splendid speeches are made, but no definite plans for future work are formulated—are not enough. Laboriously and laid, in the great key industries, for carefully, the ground-work must be a real vital rank-and-file movement, a movement which will not be something superimposed upon the workers, but which will answer their immediate needs, and will grow up out of their own efforts. In this task, the duty of guidance and leadership falls upon the Communists and the adherents of the Red International of Labor Unions. There are already signs that the British minority movement is at last getting on to an organized basis.

There is at present, for example, discontent among the miners. Negotiations are proceeding with the mine-owners, and there is a definite likelihood of a great industrial struggle in the mining industry. And it is precisely among the miners that the militant left-wing movement is growing apace. On February 16, the first issue of “The Mineworker” appeared, the fortnightly official organ of the National Miners’ Minority movement. Already two issues of this journal have appeared, and its reception among the miners has been most encouraging. After the publication of the first number, letters and articles literally poured into the office, signifying the intense interest which the miners are taking in the movement.

Miners Active.

There have recently been held district and national conferences of the militant, progressive miners, with the result that a movement, on an organized national scale, has now been started. A program of demands has been drawn up, which the rank-and-file is pressing upon the Executive of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain, urging them to make it the basis of their demands in their negotiations with the employers. The program includes such demands as: (1) Wages to be based on the cost of living, the basis of which shall be the wages paid in 1914; (2) A weekly wage to be guaranteed to all workers; (3) The six-hour day; (4) An allowance of one-fifth shift, to be paid on all afternoon and night work.

The growth of the miners’ minority movement is full of encouragement. It would be swifter if only the militant miners were in the position to finance organization campaigns. But the recent long period of unemployment, and the extremely low wages they now receive, make it hard for them to pay the expenses of putting organizers into the field.

Among the transport workers, also, there are signs of an awakening. The “International Seafarer,” organ of the seamen’s section of the International Propaganda Committee of Transport Workers, of the R.I.L.U. is being published in London, and is widely circulated among the workers in the ports During the recent dockers’ strike, the militants organized a National Transport Workers’ Solidarity Committee, which is now to become a permanent body, and is initiate the minority movement among the transport workers.

Left-Wing Conference.

Left-Wing conferences have been called, also, for the metal trades. These conferences are not of the earlier type—mainly propagandist—but are definitely for the purpose of setting up machinery for the organization of the minority movement.

Thus, there appears to be a new and refreshing movement at work within the ranks of the British organized workers. The building up of minority movements in the great unions of the key industries, the organized attempt to bring Left-Wing influence to bear upon the Trades Councils—these are the tasks confronting the militants of Britain. Especially important is such work at the present juncture, when there rules, in Britain, a new kind of government—a government, not of labor, but of labor leaders. The immense political importance of a Left-Wing movement in the trade unions—Which are all affiliated to the Labor Party—will be obvious.

After the organization of actually functioning minority organizations within the trade unions—really functioning organizations, I say, and not merely committees on paper—there will be the task of bringing the representatives of these various movements together in a national conference of the militant elements in the labor organizations. And, out of this conference, will probably be born the national organization which will co-ordinate and further the work of establishing a solid, active and growing Left-Wing movement.

Team Work Necessary.

But this means an immense amount of hard work. It means efficient team-work among the militants, and an adoption of the best organizational technique. And, as I have said, the means at the disposal of the impoverished British workers are but small. Nevertheless, the task must be accomplished; and, eventually, it will be. A good beginning has been made. It must be actively followed up. There is a ferment of discontent among the masses. It is now the task of the militants to use every effort to direct this discontent along the organizational channels which will lead the revolutionary British workers to control over their mighty industrial organizations, and thus to victory in the struggle against the capitalist class.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1924/v02a-n010-mar-28-1924-DW-LOC.pdf