Voelger on the revolutionary Belgian artist known for his woodcuts.

‘Franz Masereel: Belgian Artist’ by Heinrich Vogeler from International Literature. No. 9. 1935.

The place of the artist is in the front ranks of the fighters for the creation of a new system, which excludes both the exploitation of man by man and war. But the artist must not forget that he can achieve great art, worthy of this new world, only by relying on the beauty of the means of expression and that his creativeness under these conditions can be that stimulating driving force which is capable of shaking the human souls.

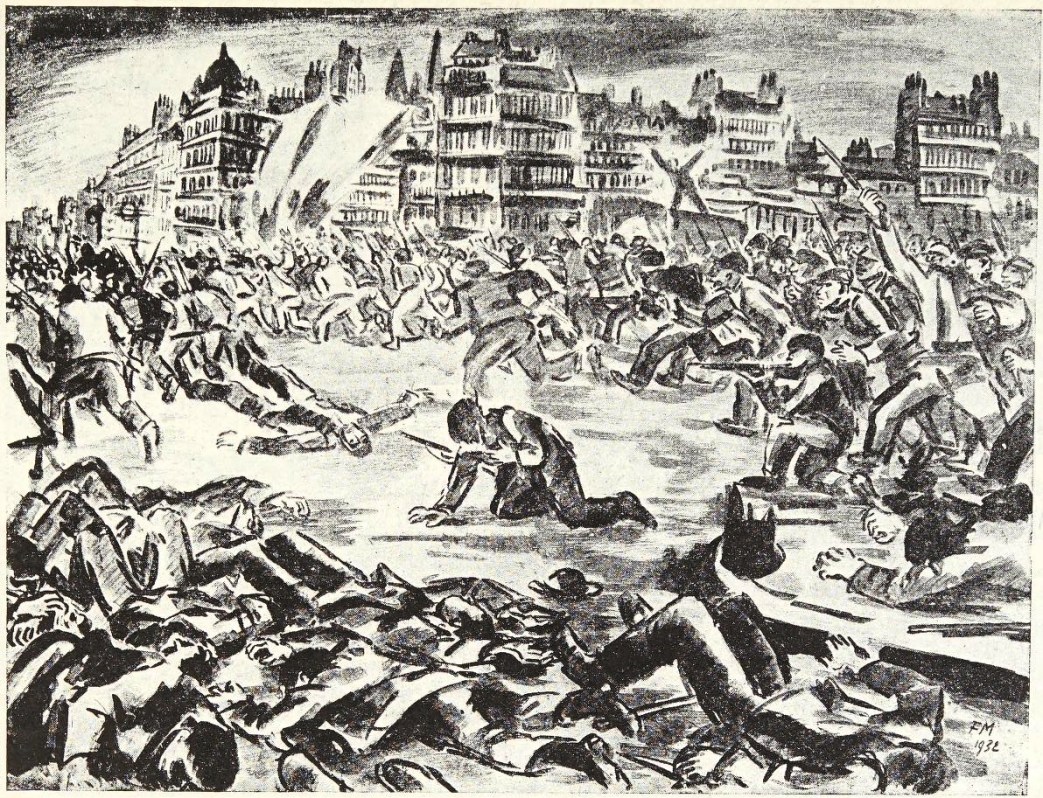

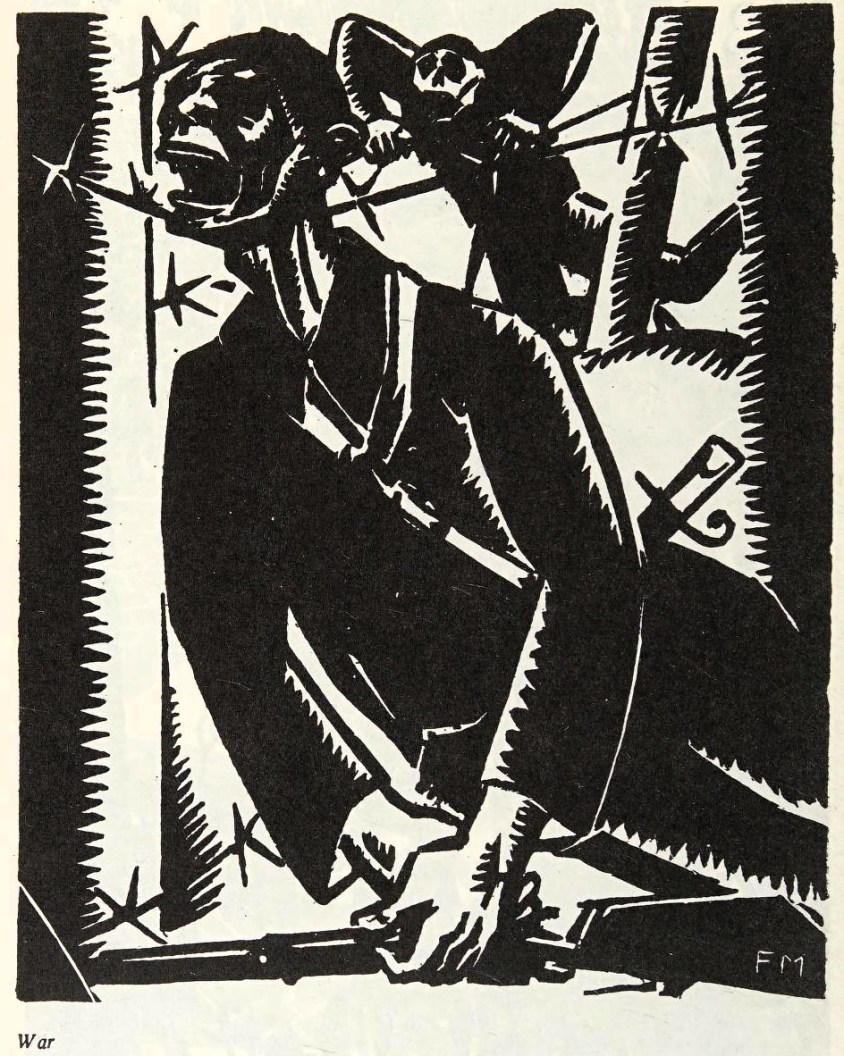

Nineteen hundred and seventeen. As the Verey lights, rising in the darkness of night, showed their surroundings and the advancing foe in glaring light to the soldiers behind barbed wire, so did Franz Masereel’s woodcuts illuminate the minds of the doubting and despairing and increase the fighting strength of those who understood. His art expressed that which millions at this time felt.

The outbreak of war drove Franz Masereel into exile; and during it he lived in Switzerland. He was twenty-five years of age; his youthful joy in Flemish fairs, sailor dances and the allurements of the city quickly disappeared…He saw something beyond. His first political drawings Masereel did for the Geneva newspaper La Feuille; and an extraordinarily large number of drawings and woodcuts sprang from this war period; it seemed as though life were too short for him to be able to express all that which he felt.

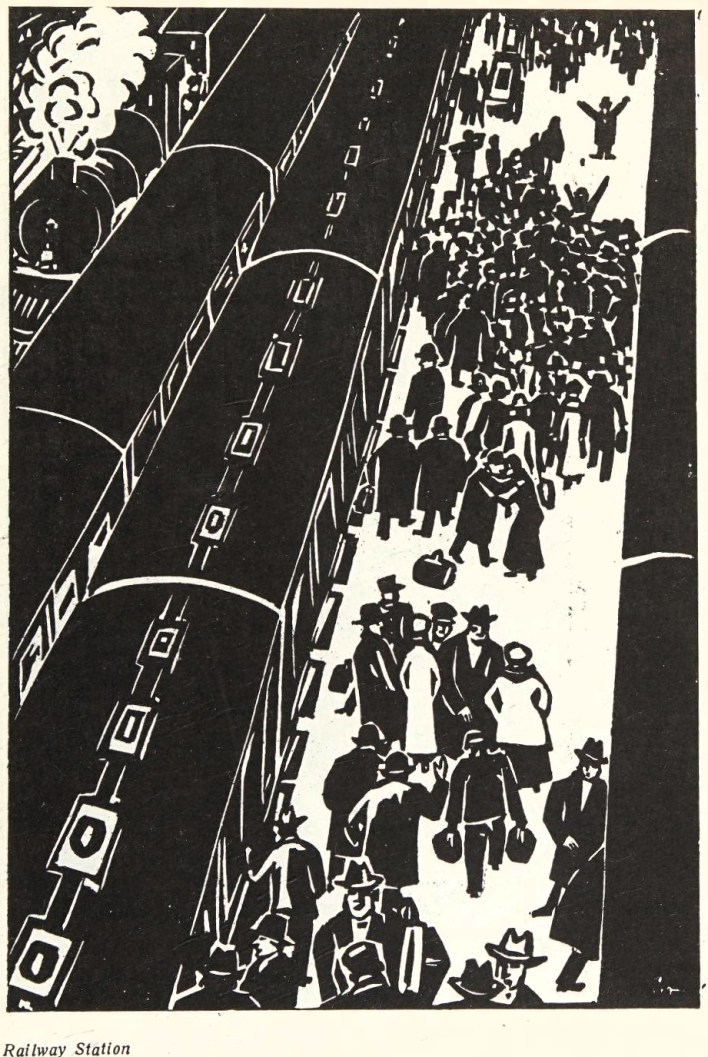

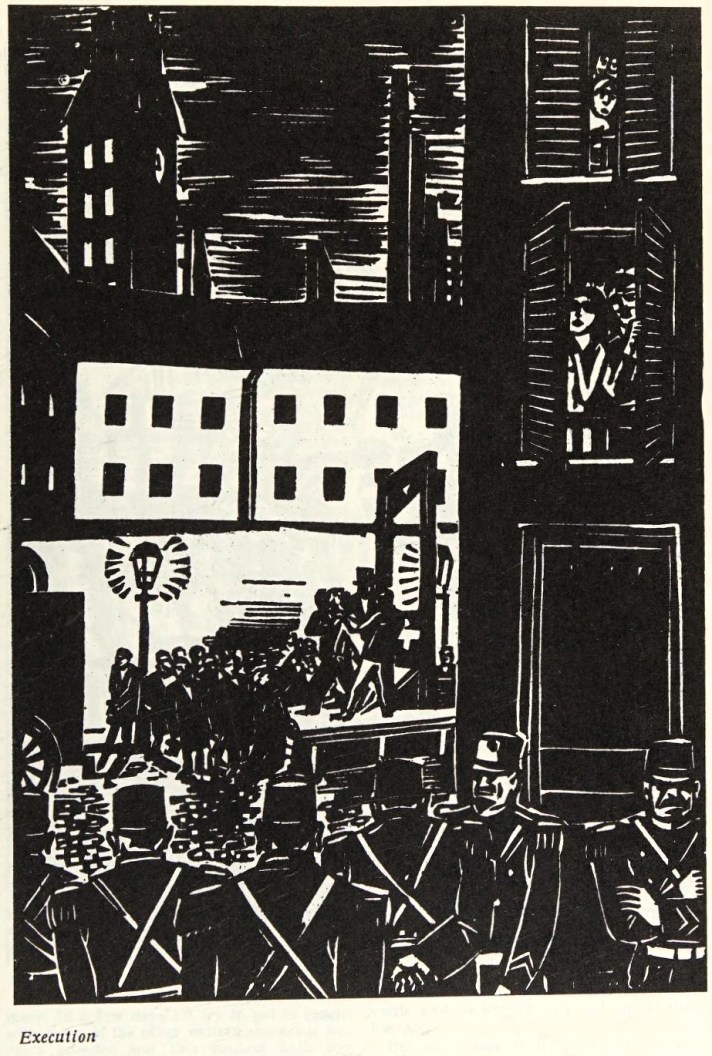

Franz Masereel held himself aloof from the conflicting tendencies within bourgeois art; he struggled to reflect the realities of this time in a spirit of social criticism and by means of the simplest artistic language. We see that nowhere does he beautify anything for form’s sake. Truth and reality in art embody his conception of beauty. He also has no love for caricature, but struggles always to convey the highest and deepest human expression. Here is the reason why his art has met with such wide international comprehension and why one returns continually to his work. He pictures the hell of the World War: headless men, bearing their own heads to the grave; men in a sea of flames, harassed by dreams of the fate of woman. He gives the passion of a human being, the evolution of a revolutionary up to the time of his shooting. Masereel’s art takes nothing for granted. Since for the artist Masereel everything, every situation, every material truth becomes a deep experience, his art actualizes an unheard of range of the feelings of humanity, their longings and disappointments, their fights and sacrifices, their life and death.

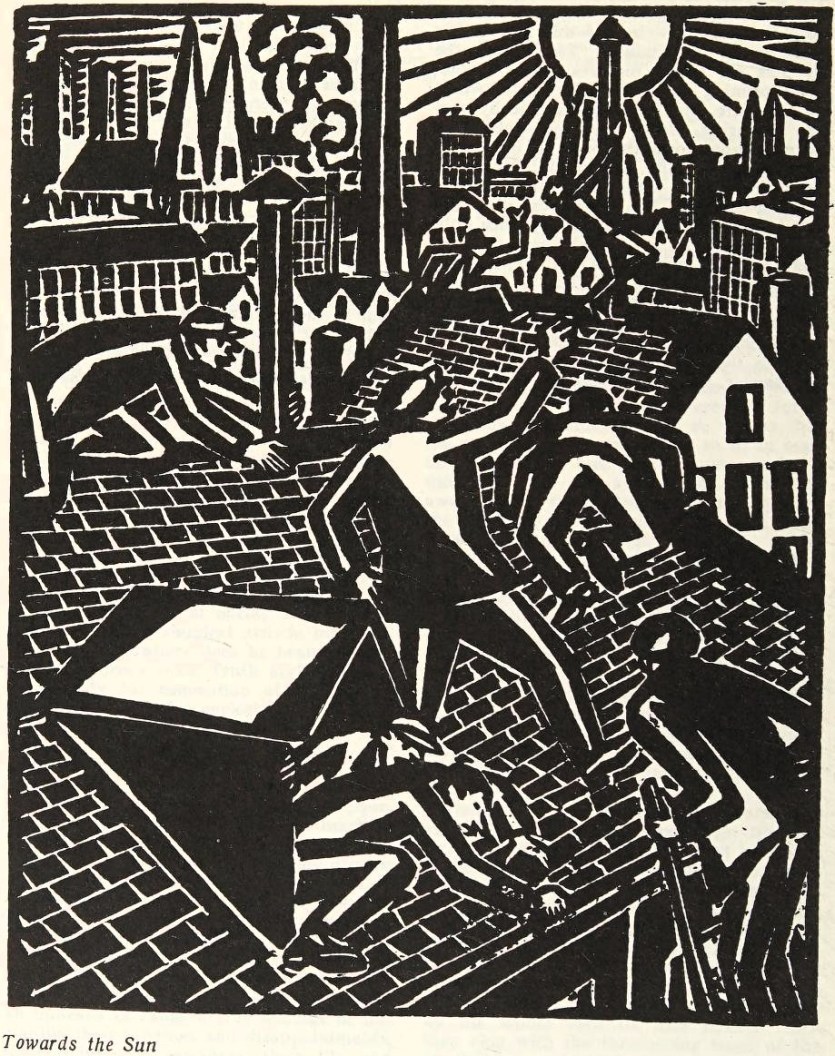

Masereel is the founder of a strong, austere proletarian lyricism within the framework of plastic art. His means of expression are simple and clear. Masereel’s pictorial language is wordless; it is filled with longing for a clear, creative world. Should he with his hunger for life throw himself into imagery, he needs no formal, esthetic symbols of expression; the reality of life, the dependence of the human race on the material facts of their surroundings, on nature for whose mastery they fight, and on the class struggle—all this supplies him with sufficient allegorical images to give spiritual events a pictorial material basis. Here Masereel has realized quite new possibilities for proletarian lyricism in plastic art. He takes the sun as a creative force, wants to unite himself with it, wishes that the seabirds would carry him to it; in another picture one sees how he opens wide an umbrella that the storm may bear him away; he lets the proletarians climb through the skylights from their cellars and tenements towards the sun, the light; or he himself climbs the highest swaying spring trees, to bind the sun in a leash. Sometimes fantasy goes astray and takes the lamp of a bawdy-house for the light and warmthgiving sun. Humor varies with disappointment. As the sun sinks in the sea, he springs after it, the aeroplane is shattered which should bring him to the sun, he must perish in its flames—but he lands as a tiny manikin on his worktable close to his woodblock, where the little imaginary fallen Masereel is met with hearty laughter by himself.

There are two things which form the subsoil of his artistic experience; the city street and the sea. With the street he shows the grinning, enticing, poisonous phantasy of the city hell, he draws the perverse types of decaying society, their luxury, their vice, the criminality of declassed elements, the glittering brightness shed over the miserable life of prostitutes, Masereel hates the town, he longs to shatter the tenements and go away to the sea! But then he is gripped by his whole love for the streets when they ring with the threatening tread of the revolutionary working masses, when they are dominated by demonstrations and when the fight against the old crumbling system begins. The sea allures him like the call of the fabled sea-maid, the siren; he flings himself from the dunes down to the shore to follow the call—but the siren of the fishing boat shrieks, calling him back to everyday reality.

Franz Masereel passed his youth on the shores of the North Sea in Blankenberghe. His youthful impressions have never left him. His paintings are best understood from the point of view of this milieu. We in Moscow unfortunately know only the sketches for many pictures, hasty memoranda pinning down the motif from working class life. But his characteristically austere colouring shows itself here also: the sea and shore form the basis of his knowledge of color. The golden-white tones of the shore seek a synthesis with the heavy greenish-blues of the sea-waves and with the stormy grey color of the sky, torn only now and then by a hopeful beam of light. Such is the North Sea in its rousing strength. So he loves it. This is not the North Sea as seen, by elegant bourgeois on hot summer days from comfortable shady basket chairs on the Blankenberghe shore—this is the mighty element with its allure and danger, from which the fishermen with heavy toil and risk of life must wrest its treasures. Such is his range of colors.

Franz Masereel has been in Soviet Russia, he saw the mighty construction, he lived to see the regulation of production planned in close connection with demand, which owing to the continual rise in cultural needs grows from year to year. Franz Masereel was also in the collective farms and recognized their economic rise—but what impressed him most was the rapid growth of cultural life in the Soviet Union, the value of man, the awakening and development of energies and talents of individuals, and above all he saw the new and inexhaustible possibilities for the development of its own plastic art.

Here he saw a wide future. He stated that art under socialism must have a dialectical character, in order to be able to express the dynamics of our time. Wall paintings must be the starting point for the new means of expression in painting. It was with the hope of some day being able to help in the working out of these problems that Franz Masereel took leave of the fatherland of the world proletariat.

Translated from German by Eve Manning

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1935-n09-IL.pdf