An important piece in understanding the nature of Hubert Harrison’s uphill intervention to get the Socialist Party to orient itself to the most proletarian of any population within the United States. This public advice (and admonishment) with seemingly elementary proposals, was given on the editorial page of the Party’s largest daily, and though the Party failed even these modest demands, they remain sound advice for for all kinds of organizing today. Unfortunately some of the words from the scan of this issue are unreadable, but none of the meaning has been lost.

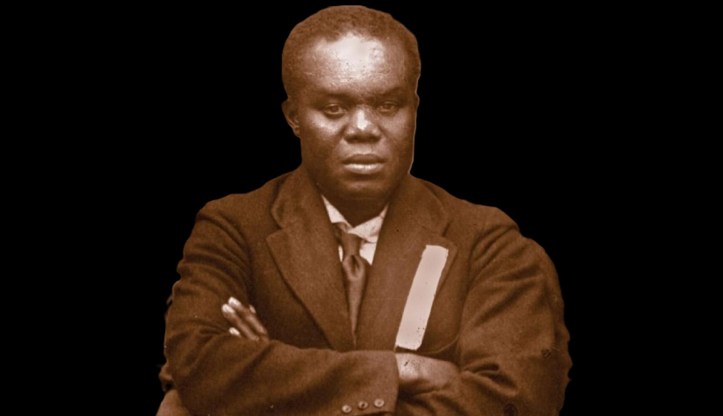

‘How To Do It—And How Not’ by Hubert H. Harrison from The New York Call. Vol. 4 No. 350. December 16, 1911.

One who comes into contact with strange people is often forced to ask himself, How shall I treat them? The answer to this varies as the culture and courtesy of the one who asks the question. The barbarian, white or black, answers, Treat them as “inferior” folk to whom one may be kind, but only as a special favor to be set off, perhaps, with a suave and careful condescension. But the truly civilized, of any color, will answer, Treat them frankly as human beings, for only by so doing can we make good our own claim to that title. This brings to mind Hamlet’s advice to Polonius, in which the difference between the two types of culture is strikingly illustrated, for these were also “inferior” folk. Hamlet had instructed the old chamberlain to see the players well bestowed, to which he replied: “My lord will use them according to their desert.” But the prince, with short patience, laid down to him the true ethics of social contact. “‘Od’s bodikins, man, much better! Use every man after his desert and who shall ‘scape whipping? Use them after your own honor and dignity–the less they deserve, the more merit is in your bounty. Take them in.”

It seems necessary at this time to tender a word of advice to many members of the party under this head. From so many of them one may hear such declarations as “I have always been friendly with colored people.” “I have never felt any prejudice against Negroes,” and so forth. All of which may be well meant, but is wholly unnecessary. If your heart be in the right place–and that is assumed at the start–it will appear in your actions. No special kindness and no condescension is either needed or expected. Treat them simply as human beings, as if you had never looked at the color of their faces. It is wonderful but true that what people will be to you depends very largely upon what you are to them. So much for personal contact.

But the real object of this article is to explain just how the work of Socialism may be carried on among Negroes. I have shown in a previous article how the bonds of allegiance in politics are breaking and how the Negro public’s mind has been prepared to listen to new doctrine. It may be well to add that the Negro vote is the balance of power in the elections in six Northern States, including Ohio, Indiana, Pennsylvania and New York. This establishes two things–that the Negro vote can be got and that it is worth getting. How, then, are they to be reached?

First, we would do well to remember the special nature of the work. Some Comrades believe that “Socialism is the same for all people–women, Finns, Negroes and all.” Quite true. But the minds of all these are not the same and are not to be approached in the same way. Even an ordinary commercial drummer will tell you this. I have already explained that the Negro has lived behind the color line, where none of these social movements have come to him. Those that did broke down as soon as they had to cross the color line. So that his mind is somewhat more difficult of approach, and consequently the work of taking the message of Socialism to him is really a special work. In the first place, the literature with which we cover a Negro district must be of a special nature. In the last campaign, Local New York got out a pamphlet entitled “The Colored Man’s Case as Socialism Sees It,” written by Comrade Slater, of Chicago, a colored minister, to which I added a special argument for that campaign. We would take one of these pamphlets and hold it up so that the title showed plainly and was [word distorted] to a colored man with it. As a eyes fell on the words “Colored Man’s Case,” his attention was arrested. [word distorted] bound Republican heelers and Democratic politicians would take it, [word distorted] they would put aside any less special literature with a wave of impatience. And having taken it, they would read it or stop to listen to our street speakers. The Debs pamphlet with the two pictures illustrating wage slavery and chattel[?] slavery was just as welcome. It is demonstrated in the territory of Branch 6 that the special literature had a effectiveness. Then there was the unique form of address. Our arguments were the ABC arguments. But we crowded them full of facts–facts for the most part drawn from the Negro’s own history and experience and hitting the bull’s eye of his own affairs every time. This did not deprive our speeches of any general effectiveness, for very often from a third to a half of our audiences is to be made up of white people, whose attention and interest were held just the same. On the Tuesday before election, when we stampeded the crowd from the opposite corner, where they had women speakers as well as men, a large wagon and [word distorted] and held about 200 of them for two hours in a drizzling rain–about two-fifth the crowd were white people. So we demonstrated again the tremendous drawing power of special addresses. And in that district they are talking about yet–all of them–doctors, lawyers, longshoremen, clerks and waiters.

Now, for such work a special equipment is necessary. One must know people, their history, their manner of life and modes of thinking and feeling. You must know the psychology of the Negro, if you don’t you will fail to interest or impress him. You will fail to make him think–and feel. For many of your arguments must be addressed to his heart well as to his head. This is more true of him than of most other American groups.

It stands to reason that this work be better done by men who are themselves Negroes, to whom these conditions come by second nature. If they are intelligent and well versed in the principles of Socialism they can drive home an argument with such effectiveness so a white Socialist must despair of nothing. And this brings me to the question of colored organizers. Comrade Debs said that there are already three or four such national organizers. I know one, Comrade Woodby, of California. He has been very effective. There should be more. But there is no need to wait until we can get colored national organizers. It ought to be taken up by the various local and State organizations. Something the sort is needed right here in New York where we have a Negro population of 100,000 in the city alone. The work must done if the party would not be derelict of its duty, and it should be done in no halfhearted way. For it is not a question charity. Does the Socialist party feel that it needs the Negro as much as the Negro needs Socialism? That is the question. What is the answer? If we feel that we can advance to the conquest of capitalism with one part of the proletariat against us, let us say so. But I haven’t the slightest doubt that our program requires all the proletariat, and we are all aware of that. Let us act, then, in the light of knowledge and add to the strength of an organized, all-inclusive, class conscious working class movement.

The New York Call was the first English-language Socialist daily paper in New York City and the second in the US after the Chicago Daily Socialist. The paper was the center-right of the Socialist Party and under the influence of Morris Hillquit. The paper is an invaluable resource for information on the city’s workers movement and history, it is one of the most important socialist papers in US history. The Call ran from 1908 until 1923, when the Socialist Party’s membership was in deep decline and the Communist movement became predominate.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-new-york-call/1911/111216-newyorkcall-v04n350.pdf