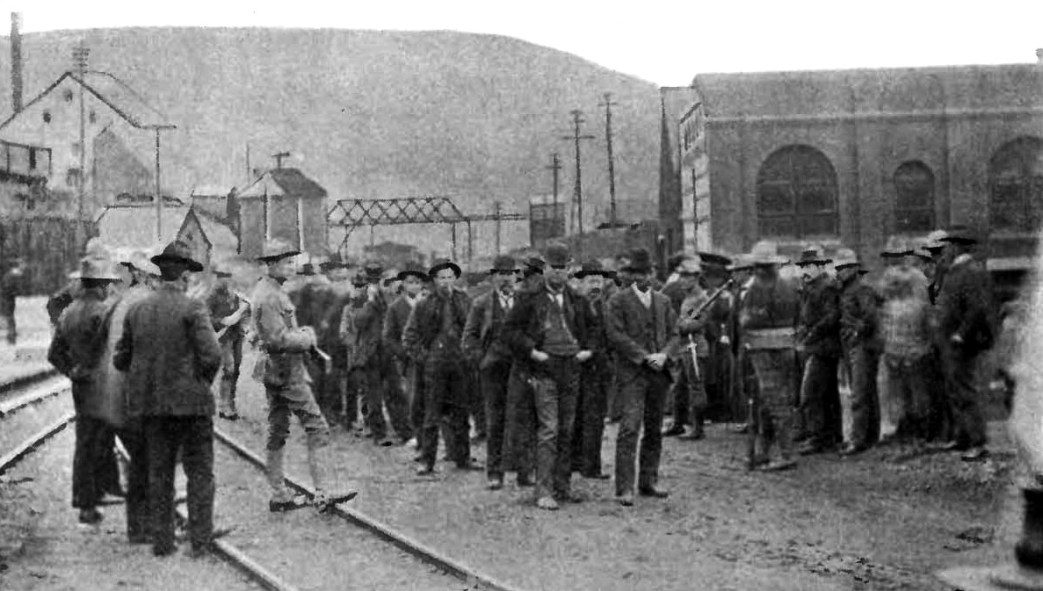

Grievances and demands from the 1903-4 Colorado Mine War. Another dispatch from the Colorado camps on the unbearable conditions imposed by Rockefeller’s industrial regime that the strike was a rebellion against.

‘From Birth to Death’ by Bertha H. Mailly from American Labor Union Journal. Vol. 2 No. 19. February 11, 1904.

Coal Companies Grip Never Relaxes. Scrip Payment, Forced Trading, Compulsory Assessment and Petty Annoyance, Make the Coal Miners’ Life a Veritable Hell. The Grievance and Demands of the Strikers.

Trinidad. Colo. The grievances of all the mining camps in this district are practically the same, for the miners have to deal with the same masters. These grievances are but repetitions of all that have come to light in previous great coal strikes in other parts of the country, and find but a very moderate expression in the formulated demands which the striking miners have presented to the companies. To take as authority the word of those who have had experience in similar strikes, in no mining camps elsewhere has there been worse slavery than here in Colorado.

The specific demands of the strikers relate only to their work in and around the mines and scarcely touch the hundred and one details of infamous tyranny which surround and intensify the struggle for existence.

The miners ask for an eight-hour day. That eight-hour day is theirs by right, by the expressed will of the majority of the citizens of Colorado, and is denied them because it has been set aside as unconstitutional by a corporation-owned court.

The miners ask also that all wages be paid every two weeks instead of monthly and that all payment in scrip be abolished. Under the present system each workman is paid at the end of the month, if anything is coming to him, with a bank check. During the month if he needs any money for the necessities of life he receives it at the office of the company in the form of scrip notes, for which, if he buys his goods of the Colorado Supply Co. (the company’s store) he receives the face value. If he chooses to trade elsewhere the notes are worth 10 or 12 per cent less than their face value. Now, consider that the Colorado Supply Co. charges much higher prices for goods than outside firms, and you will see why the miners refuse to submit any longer to this imposition. The scrip method of payment was formerly the universal system in mining regions all over the country, but has been nearly abolished in the mining states east of the Mississippi through the power that the workers in the mines have gained by their organization.

The 20 per cent increase in wages is little enough to ask, but unless the payment in scrip is done away with at the same time this circle of robbery by which the companies make both ends meet will leave the miner, no more in return for his labor than he received before.

The same old system of forced assessments takes place here as in other parts of the country. One dollar a month for medical attendance, 50 cents. for blacksmithing, 25 cents for maintaining school advantages, etc., etc., and these assessments the miner finds subtracted from his pay if he has been in the mine not more than half a day during all the month.

According to the legal standard of weight in the United States 2,000 pounds constitute a ton. Heretofore the companies in Colorado have required from the miners 2,500 pounds ton, or that each workingman shall give to the company 25 per cent on each ton he mines. The miners now demand that the companies comply with the law.

The last on the list of the strikers’ demands is perhaps the most vital. It is that the company take adequate measures to insure a plentiful supply of fresh air. There are laws in every mining state requiring precautions in regard to ventilating fans, the staring of dynamite, etc., and yet the mine disasters, which no daily newspaper is without, show the ruthlessness of mine owners in breaking laws which are contrary to their interests and disregard for human life.

Such are the demands of the striking miners. And yet they give voice to only a few of the wrongs the miners and their families are forced to endure. I have been unable to find any activity uncontrolled by the companies: from the birth of the child, for which the services of the company doctor must be employed, ofttimes unwillingly, through school and church and daily labor, through sickness and death the grip of the company is never relaxed.

The companies own almost entirely the miserable houses. They own the land upon which the houses stand. Instances have been told me where their agents have ordered tenants not to set pails or anything on the ground outside of the tiny huts, saying that the rent was paid for the houses, but not for the land.

The companies own, as well, the school system. Out of the school assessment of 25 cents from each miner they generously build school houses, in which they place teachers chosen by school boards composed of superintendents and mine bosses, which perhaps a moderate proportion of members of the Citizens’ Alliance, the Anti-Union organization. The teachers teach from books prescribed (and changed each year) by the school board, and paid for by the miners. This custom of changing text books yearly is one of the innumerable grafts of the companies. Another one that pays well is the saloon business. In four different camps under control of the Victor Fuel Co. two saloons pay each, as license to the company, 20 cents for every man on the payrolls, about $800 per month for the company.

The company store is a sore grievance. The owners, a group consisting of members from each of the mining companies, claim that no one is forced to buy there. Does not the system of scrip payment seem a pretty effective means of forcing? Competition is not permitted to grow very lively, for if an outside man comes into camp and attempts to sell anything he is taken before the local justice, also owned by the company, and promptly fined from $1 to $50. One incident will serve to illustrate the non-forcing process: A woman who had been ill wanted some broth and ventured to buy a chicken of a neighbor who had a little vegetable patch and raised a few chickens. A company agent saw her carrying it home and asked her roughly what she had.

“Just a bit of chicken I got of John because I was sick.”

“Why didn’t you go to the company store?” he demanded.

“They haven’t any chicken,” she answered timidly.

“You can get all the meat you need at the company store–you. You can tell your man to come and get his time.”

Let me mention incidentally that Rockefeller controls 70 per cent of the stock of the Colorado Fuel & Iron Co., and that the miners’ families pay 25 cents a gallon for Rockefeller’s oil at the stores of the Colorado Supply Co. The United States postoffice in each camp is always located in the company store. The manager of the store is always the postmaster, receiving a salary therefor, and the work of the postoffice is done by the cashier of the store, who is an overworked drudge and whose services thus cost the manager nothing.

There seems to be no question that mails have been tampered with during this strike in some of the most closely guarded camps. I have been told on direct authority of letters sent to persons in one of the most inaccessible camps which were never received. Labor papers sent through the mails scarcely ever reach those for whom intended.

The climax of all this robbery and perhaps its most hateful form is in the medical department. Each man working in and around the mines is taxed $1 per month for service for himself and family. Some estimate of the company’s Income from this source may be made from the following figures, which are authentic:

Total hospital fees collected at Hastings, Gray Creek, Delagua and Chandler (Victor Fuel Company) each month about $2.300.00

Monthly cost of medical attendance, etc. 850.00

Excess of collections monthly. 1,450.00

Multiplied by 12

Excess of collections yearly. 17,400.00

There is said to be more than $60,000 hospital fund not accounted for in these four camps.

The company hospital is at Pueblo and is claimed by its owners to be the finest in the country. It ought to be when the cost to the miners is considered. It is a journey of from 150 to 200 miles from many of the camps to Pueblo and after being brought there the sick and injured men are often left lying in the railroad station for hours before being taken to the hospital. It is a sufficient commentary upon this subject to report that the women of the camps universally hate both company doctors and the company hospital. I have heard more than one woman say:

“I’d rather have my man die at home than take the chances on sending him to the company’s hospital.”

It is impossible to do more than suggest a few of the wrongs of the workers who live in these isolated and pitifully dreary camps. Their lives are all one vast wrong and even a hasty glimpse caught in a few days’ visit in the region makes you feel the desperate struggle before them. But not hopeless, as you realize the great growth that is taking place in the comprehension of their class wrongs am in the knowledge that the remedy for these must come through class loyalty and class organization.

American Labor Union Journal was the official paper of the ALU, formed by the Western Federation of Miners and a direct predecessor to the I.W.W. Published every Thursday in Butte, Montana beginning in October, 1902 before moving to Chicago in early 1904. The ALU supported the new Socialist Party of America for its first years, but withdrew by 1904 as the union and paper grew more syndicalist with “No Politics in the Union” appearing on its masthead and going to a monthly. In early 1905, the Journal was renamed Voice of Labor, folding into the Industrial Workers of the World later that year. The Journal covered the Western Federation of Miners and the United Brotherhood of Railway Employees, as well as the powerful labor movement in Butte.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/american-labor-union-journal/040211-alujournal-v2n19.pdf