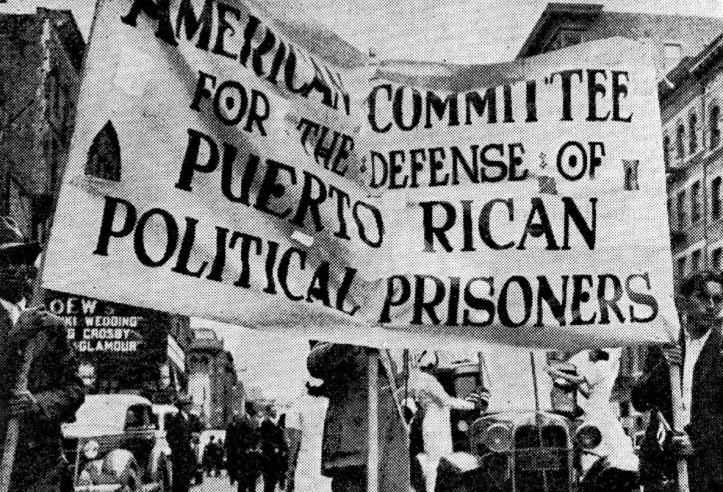

The context in which occurred March 21, 1937’s ‘Ponce Massacre’–the police murder of seventeen Nationalist Party marchers commemorating the end of slavery in Puerto Rico, The island was then ruled by Governor Blanton Winship, the Macon, Georgia-born former football player and career-military veteran of the Spanish American War sent to colony by F.D.R. to suppress the island’s labor upsurge and its growing Nationalist Party.

‘Terror in Puerto Rico’ by John Buchanan from New Masses. Vol. 25 No. 1. September 28, 1937.

The regime of Governor Winship, protecting the sugar investments of Wall Street, has been responsible for a virtual civil war there

NOT all of your sugar comes from Cuba. Some comes from Hawaii, some from the Philippines, a little from Louisiana.

A lot of it comes from Puerto Rico. The next time you put a lump of sugar in your coffee think of this.

Think of eleven gallant fighters against imperialism, lawyers, students, university graduates, leaders of the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico. They have been buried alive for half a year in the medieval fortress of La Princesa, in the shadow of the ancient battlements of El Moro in San Juan. They have been held under bail totaling a quarter of a million dollars. As this goes to press they have been taken from La Princesa.

Under heavy guard they were rushed across the island. The cars they rode in rolled over mountain roads that reveal vistas of breathtaking beauty, between fields that at this time of year breathe the heavy-sweet scent of sugar cane. They were taken to the town of Ponce.

Ponce is one of the oldest towns on the island. It is one of the most Spanish. Physically, the twentieth century has scarcely touched it. In one of its ancient courtrooms the eleven men have faced a jury made up of plantation managers and cipayos. (A cipayo is a Puerto Rican who licks the boots of his American oppressors.) They are being tried for murder.

They are being tried in connection with the brutal police massacre that took place in Ponce on March 21, Palm Sunday. Just how eleven Nationalists, most of whom were not even present, can be responsible for the slaughter of eighteen helpless citizens by the police and the wounding of nearly two hundred more is a mystery that only Governor Blanton Winship and a few of his police tools can answer. Hundreds of police, scores of G-men, and “experts” of all descriptions have been working for months to prove the connection.

The trial, which began September 13, is an event of major importance. Its causes and its consequences touch the lives of millions of Americans. Yet you will not find the details in your local newspapers.

That sounds startling, but the reason is simple. The correspondents of the American press in Puerto Rico are Governor Winship’s publicity men. Take Harwood Hull. He supplies both the Associated Press and the New York Times; and both he and his young son are on the Winship payroll. Hull is a prosecution witness in this trial.

That is why you see so little news about the struggle for Puerto Rican independence. That is why you see no news at all about the campaign of terror and intimidation that is being carried on by Winship and his clique, the rough and ready business agents of the sugar trust. Winship is particularly anxious to avoid publicity on this case.

From what news about the trial has come through, in the Spanish-language press, it is known that eleven out of the twelve jurors are self-declared enemies of independence. (Seven are Republicans, four “Socialists,” one a liberal.)

Pérez Marchand, former prosecuting attorney (resigned) who conducted the first investigation of the “crime” now being tried, is a defense witness.

Hardly had the trial opened when it was announced that ten more Nationalists had been arrested in Guánica, sugar capital of the south coast. Nationalists are being arrested on every conceivable charge. Sympathizers are being arrested for the crime of collecting money for the defense.

One witness stated that he was not testifying of his own free will, that he had received a bribe from government agents, and that he had contributed the sum of the bribe to the defense.

IN ORDER TO UNDERSTAND the war that is raging in Puerto Rico–for it is war as surely as Hitler’s “revolution” was war–it is necessary to go back a few years.

The United States acquired Puerto Rico in 1898. A fact conveniently forgotten by most American historians is that, when we grabbed the island from Spain, Puerto Rico had already been granted autonomy. The act had been signed by the Spanish crown but was not yet in force, pending the outcome of the war. Then the American imperialists stepped in. Puerto Rico is still struggling to win some form of autonomy.

Under American rule there were rapid economic changes. Small land holdings began to disappear. Spaniards who held larger tracts of sugar lands sailed for home, leaving American banks to buy up the holdings dirt cheap. Absentee ownership became the rule instead of the exception. Meanwhile there were “improvements.” The American authorities introduced modern sanitation and hygiene. The birth rate went up. It is still up. Á high birth rate means cheap labor.

There were also improvements of the mind. The great, benevolent power of the North prepared a program of enlightenment for its little, brown children of the South. “Americanization” was begun on a grand scale. It tried to extirpate the Spanish language by forcing Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican teachers to teach all their classes in English.

This has had several results. First, it has provoked bitter resentment on the part of most Puerto Ricans. Second, it has produced a small class of pitiyanquis or cipayos, who today are the native apologists for American imperialism. Third, it has produced a new, hybrid English-Spanish dialect to puzzle future etymologists.

The rapid expropriation of the native land-owners, first the small and then the big, caught the Puerto Rican worker between the blades of an economic scissors. Deprived first of land and then of his source of home-grown food, not only did he have to work for the absentee landowner at low wages, but he also had to import all his food from the United States at shockingly high prices. Nothing was grown in Puerto Rico except export crops.

Cheated of autonomy when the American imperialists brought them “freedom from the slavery of Spain,” the Puerto Rican leaders never ceased to struggle for political freedom. Finally, in 1917, they won American citizenship. The Jones Act provided for an elected legislature with limited powers. It gave Puerto Rico a resident commissioner at Washington, whom the Puerto Ricans have to pay for sitting in Congress without having the privilege of a vote. It left the office of governor to be filled by appointment by the President of the United States, and the governor was to appoint men to fill most of the key positions in the insular government. This was something, but not much.

In 1919 a delegation of the Unionista Party traveled hopefully to Washington. At a hearing before the House Committee on Insular Affairs, they asked for a popularly elected governor. Began a curious game of pass-the-buck between Washington and San Juan, the island capital. Our peculiar form of bourgeois democracy supplies a perfect machine for the breaking of promises. One administration is not bound to keep the rash promises of its predecessor. And the Harding regime was noted for its promises.

In 1924 the United States Senate passed a bill giving Puerto Rico the right to elect its own governor, but no action was taken by the House of Representatives.

In 1926 the House passed a similar measure, but the Senate adjourned without taking action. By now this gesture has become so familiar that not even the most trusting cipayos put any stock in it.

The above bills were backed by the Unionista and the Alianza Parties, the then dominant political parties of Puerto Rico. The so-called Socialist Party of Puerto Rico, bowing to the necessity of assuming an “advanced” position, began to mumble vaguely about “statehood.” It worked.

In 1928, on the eve of the depression, the insular elections turned into a Socialist landslide. The island voters, disillusioned with both the Alianza and the Unionista politicians, turned to Santiago Iglesias, leader of the Socialist Party, as their last hope for some form of autonomy. Their cause could not have been placed in worse hands. Iglesias, once a radical, is now working in a majority coalition with the quasi-fascist Republican Union Party. He is one of the bitterest enemies of the struggle for liberation.

So far the independence struggle had been carried on with all the amenities of bourgeois politics, and with Spanish courtesy besides. Militancy was lacking, there was not even any rough talk. Only the Independentista Party, a handful of young intellectuals, dared to talk of revolt.

THEN came the crisis. It served to speed up the process of expropriation that had been going on steadily for years. Large tracts of sugar land that were still independent and native-owned tumbled into the tills of the National City Bank and the Chase National Bank by the mortgage-foreclosure route. Absentee ownership grew until 85 percent of the sugar lands were in the hands of foreigners. Land starvation spread from the small peasant and the petty bourgeois to the upper strata of the native owning class.

Wages fell. Before 1929 the family of a worker in the sugar cane fields had only about two hundred dollars a year to live on. Now the peones worked for half of that, a third, whatever they could get. Half of the island’s workers were unemployed. Before the depression, poverty was abysmal. Workers in Puerto Rico lived on a standard lower than that of the poorest southern sharecroppers. Now it was worse, indescribably worse for the masses of Puerto Rico. And the blessed birth rate that had come with American “freedom” was adding thirty-eight thousand new workers to the unemployed count every single, blessed year.

The Roosevelt administration, through the Puerto Rican Reconstruction Administration, has allotted between sixty and eighty million dollars to be spent on the island for relief. It has been found that, far from relieving the crisis, this paltry sum will care for only about half of the normal, annual increase in population. Early in the game, it was easy for the Puerto Ricans to see that government relief was not the answer.

It was easy to see that behind all of Puerto Rico’s troubles lay one, big thing: the land monopoly. It was easy to forget that other causes were involved, causes equally a part of the complicated structure of the capitalist system. The time was ripe for a militant, revolutionary party to appear.

It appeared. It was called the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico and on its banner was inscribed the slogan: Land and Bread!

Because there is no mature labor and trade-union movement in Puerto Rico, it had certain special characteristics. It attracted some of the most brilliant of the younger intellectuals, mostly middle class youth. Pedro Albizu Campos, a Harvard graduate and a former admirer of Ghandi, became its leader. Though comparatively small in number, so great was the influence of the Nationalist Party that the other political parties, seeing which way the wind blew and fearing to lose their mass support, began waveringly to adopt the issue of independence.

Albizu told his followers that the sugar barons would never give the island further autonomy, or statehood, or, least of all, independence. There was no use in sending delegation after delegation to Washington. The only hope of the Puerto Ricans lay in wresting their island by force out of the grip of the monopolists. Albizu’s movement swept the island. Complete independence became, and still is, the leading topic of conversation, the center of discussion in the newspapers, the uppermost thought in the minds of the vast majority of Puerto Ricans. And Albizu was right about the sugar barons.

Puerto Rico is God’s gift to the sugar interests. There they can raise and refine sugar almost as cheaply as in Cuba and export it to the United States tariff free. The resulting profits are fabulous. The whole absentee investment in Puerto Rican sugar, for instance, is only about forty million dollars, yet in the years 1920-35 three of the big sugar companies alone made more than eighty million dollars in profits. Added to that, the same banks have a rich investment in insular and municipal bonds, a railway, a power company, and sundries. Three northern steamship lines do a rich trade in freight to and from Puerto Rico, sharing a virtual monopoly.

The demand for independence threatened this bankers’ paradise. The danger brought out all the latent fascism. What the Liberty League crowd tried to hide at home, they did not bother to conceal in Puerto Rico. And they found their Führer in Major General Blanton Winship, LL.B. and LL.D. Experienced in the Philippines and in Liberia, he knew all the ins and outs of imperialism. A former judge-advocate general, he knew all the tricks and loopholes of the law. He landed on the boiling island like a pitcher of ice water.

WITH WINSHIP at their head, the insular police threw away their kid gloves and bought a flock of machine guns. Meetings were broken up. Nationalists were terrorized. In the fall of 1935 they killed four Nationalists at a student demonstration on the campus of the University of Puerto Rico.

Persecution drew more and more sympathy to the Nationalists. It became increasingly obvious that the foreign exploiters were willing to go to any lengths to protect their profits and made the Nationalists even surer that force was the only possible answer. Some of the younger element began to think in terms of direct action.

Elias Beauchamp, a young Nationalist, shot and killed Francis Riggs, the chief of police. Police immediately seized him and a friend, Hiram Rosado, whom they happened to recognize as a Nationalist. They took both boys to the San Juan station, and, on a flimsy pretext, killed them without the formality of a trial.

A political crisis resulted. In Washington, the Tydings Bill was introduced. The Tydings Bill was one of the crudest instruments of political revenge in the history of the country. It offered the Puerto Ricans independence on terms that were like offering a beggar a rope and inviting him to hang himself. The motive was to be rid of all talk of independence for all time. The Marcantonio Bill, introduced shortly afterward, did a little to neutralize the bad smell of the Tydings Bill.

But Puerto Rico was under a reign of terror. Police, national guard, and the regular army were mobilized on a military basis. Police hunted down Nationalists in every town and registered them like criminals. Permits for parades and meetings were refused. On one occasion police and soldiers surrounded a church and denied the people entrance. Pressure was brought on the newspapers. Radio wires were cut when a speaker said anything that might be construed as sympathetic to the cause of independence. Every effort was made to prevent the Nationalists from reaching the masses with their messages.

Civil service employees with independent sympathies were intimidated and hounded out of office. They were replaced with pseudo-American newspaper writers and others whose job it was to spread the propaganda of reaction. Political discussion was barred at the University of Puerto Rico. A lynch spirit was generated against all Nationalists. It was fascism at its nakedest.

Albizu Campos and seven comrades (the Winship machine always knocks off its enemies in round numbers of eight or ten) were arrested and indicted on the charge of attempt to overthrow the United States government by force. Reams of patriotic propaganda were thrown out by the Winship scribblers. It has been said that the panel from which the Albizu jury was to be selected was carefully checked over by the prosecuting attorney and his friends at a cocktail party in the governor’s mansion to see who was “okay.” It is also said that the trial judge openly voiced his prejudice. The jury selected proved quite “okay” from the Winship angle. It found Albizu and the others guilty. Today they are serving sentences of six to ten years on that fantastic charge.

Some thirty-six hours after passing sentence on Albizu–so it was said–Judge Robert A. Cooper was driving across the Dos Hermanos bridge between San Juan and Santurce. It is a lovely spot for a murder. Any marksman who could hit the broad side of a barn with a pitchfork could not possibly miss his victim there. While the judge was on the narrow bridge–so the story goes–a car full of men drove up. Some fifteen shots were fired, none of them doing any damage. How the judge escaped is a miracle.

THE INCIDENT was supposed to impress the people of Puerto Rico and the United States with the fact that all the Nationalists were not yet out of the way. Some of the “maniacs” were still at large. That happened on June 8, 1936. Within the past two weeks ten Nationalists have been arrested and held for murder, accused of that “crime.” The list includes, curiously, all of the important leaders of the Nationalist movement who do not now happen to be in jail on some other charge. It includes also, Julio Pinto Gandia, acting president of the party, who is in jail on another charge.

On March 21, 1937, Palm Sunday, the Nationalists tried to hold a parade and mass meeting in Ponce. They may have picked Ponce because it was as far as possible from the seat of the Winship government. Pressure was brought by the governor on the mayor of Ponce not to grant a permit. Nevertheless the mayor did grant a permit. Colonel Enrique de Orbeta, the governor’s chief of police, rushed to Ponce to persuade the mayor to change his mind. With him he took the police of fifteen surrounding towns and, to use the words of the governor’s report, “clubs, carbines, revolvers, tear-gas bombs, and some machine guns.” His excuse for denying the permit was that it was to be a “concentration of military forces.” In other words, some of the young Nationalists wore uniforms though none of them were armed in any way. The mayor changed his mind at the last minute when the parade had already formed and a crowd of hundreds had gathered to watch. The police surrounded them, outnumbering them two to one and blocking off the street in both directions.

In a supreme demonstration of cold nerve, the Nationalists decided to march. They would march in support of the civil liberties that had been granted them in 1917 and never (legally) revoked. The police cut loose with their guns. [For details of what followed see the NEW MASSES of June 8, 1937.]

The score was eighteen killed and some two hundred wounded. The police fired from so many directions that they were caught in their own cross-fire. Two policemen were killed. Maddened by the smell of blood and powder, or perhaps by the horror stories that had been poured into their ears by Winship stooges, the police ran amok, killing people who were three and four blocks away from the demonstration. No policeman has been found guilty of any misconduct in the affair. Quite the contrary. Of Colonel Orbeta, who was responsible, Winship said in an interview with the press that he “is the best police officer I have ever met.” But eleven civilians are being tried this week for the murder of those two policemen, eleven leaders of the Nationalist Party, most of whom were not even present when the slaughter took place. The names of only ten have been released. They are Julio Pinto Gandia, Plinio Graciani, Tomás Lopez de Victoria, Casimiro Berenguer, Martin Gonzalez Ruiz, Elifaz Escobar, Luís Angel Correa, Santiago Gonzalez, Luís Castro Quesada, and Lorenzo Pineiro.

And the details have not appeared in capitalist papers. But whatever you read, whatever you hear, remember that it is Puerto Rican independence that is on trial. Also remember that the issue of the trial is baldly stated: profit for the Rockefeller-Morgan banks or life for the people of Puerto Rico.

The foregoing events have brought the masses of the island flocking to the cause of independence. The Nationalists stand in the forefront of the struggle. In jail, under persecution, they have proved a stronger force than ever before. People of all classes have rallied to their defense.

But they realize now, those Nationalists, that their staunchest supporters have been the workers. They are beginning to feel that, if their movement is to be successful, it will have to become a part of the world movement of the proletariat. They are anxious that the loyalists should win in Spain quickly, gloriously. Why? They will tell you that it is because a victory for the People’s Front in Spain would break the hold of the Casinos Españoles, one of the centers of densest reaction in Puerto Rico. It would make possible a people’s front in Puerto Rico. With their eyes on Spain, they see that the problem reaches far beyond their little island. And there is a new party in Puerto Rico to help them toward that people’s front and victory. It is called the Communist Party.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1937/v25n01-sep-28-1937-NM.pdf