The exploitation of land and labor is a single process. Many new technologies could ease and shorten labor while increasing productivity, allowing more to work less. Instead….

‘Coal Mining by Machine and the Changes It Has Brought’ by Glenn Warren from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 18 No. 5-6. November-December, 1917.

In the southeast part of Kansas and the southwest part of Missouri are thousands of acres of coal lands where the coal is from ten to forty feet below the surface. Up until five or six years ago this coal was mined from the earth by two methods. The coal near the surface–that is, from ten to twelve feet deep—was reached by “stripping” or “daylight mining,” as it is called. All this digging had to be done by teams or hand and it was necessarily a costly process. The coal at a greater depth was obtained by underground mining.

Both of these methods required skilled labor more or less, either experienced teamsters and teams or skilled miners. As one old-timer expressed it, “Them days a man could make a real day’s wage,” it being easy for a good miner to make from five to seven dollars per day, and flourishing mining towns and camps dotted the country everywhere.

Today, however, all is changed. The streets of the one-time populous, prosperous mining towns of this region are almost deserted, the stores have mostly been closed up and camps have disappeared. The men and laborers are of a different class and the majority of them are now paid from two and a half to two dollars and eighty cents per day. Yet with all this more coal is being shipped out of this section than ever before. Where formerly one man in an underground mine could load about nine cars, eight men in one of the daylight mines a few days ago loaded two hundred cars in eight hours.

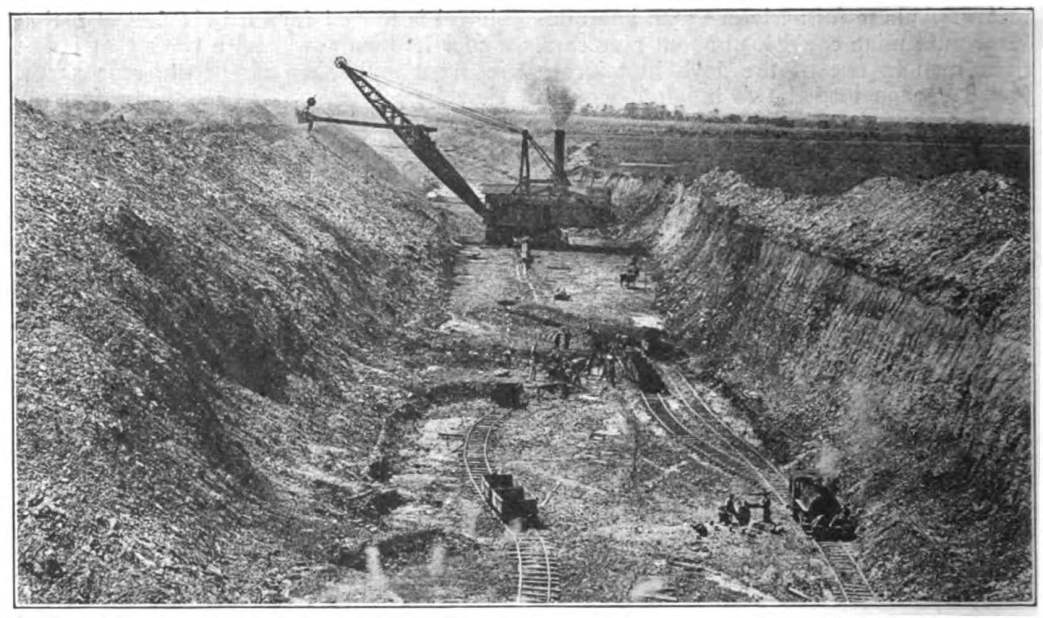

This enormous change has been entirely due to the introduction of monster steam shovels. Machines, larger than any of their kind in the world, that takes several tons of earth and rock out of the ground and move it to a spot two hundred feet away with as much speed and ease as a man can take a shovelful and move it ten feet, are now used.

When a vein of coal is to be worked a railroad spur is first built to one edge of the deposit, as near as can be determined. Here a tipple or loading station is built, having shakers to sort the coal into different sizes and drop it into the proper railroad car. A hoisting engine is also provided to draw the small cars from the pit up an incline where they can be dumped onto the shakers.

The steam shovel then starts work, making a trench as wide as the shovel will permit, generally about seventy-five feet wide at the bottom and about a hundred and twenty-five feet at the top and deep enough to uncover the vein of coal. The shovel is moved forward six feet at a time under its own power on a track that is laid in front and taken up in the rear as the shovel progresses. Nearly thirty feet are covered in eight hours. This, of course, depends upon the condition of the earth and the depth.

About a hundred feet back of the shovel small blasts are put in, in order to loosen the coal, which is shoveled into small cars, holding about a ton each. These cars run on narrow gauge tracks which are laid as the work progresses and they are hauled back to the incline by a small donkey engine. After the width of the vein has been traversed, or after the shovel is too far from the loading station to make it profitable to go farther in this direction, a lateral is started nearly at right angles to the main trench. When, because of the two limiting conditions stated above, or others, it is necessary to discontinue in this direction, the shovel is brought back to the main trench and started again in the same direction parallel to the first lateral. The earth dug out this time is dropped back into the old lateral, thus filling it up as the work advances.

By this method the labor necessary to shovel the coal into the cars is considerably less than in the underground mines, as well as less dangerous, and shot-firing here is little more dangerous than shoveling coal, while in underground work all shots must be fired when the men are out of the mine and the shot-firer is one of the highest priced men on the payroll. The men who shovel the coal into the cars receive about two dollars and a half per day. In some strip pits smaller steam shovels follow up the large ones and load the cars.

Although it is difficult to get accurate figures on the exact ration between the cost of mining coal in open mines and the cost in the underground mines, it is pretty certain that the cost in the open mines is little more than half. This is not only due to the fact that the labor required in the open mines is less, and lower priced, but also to the fact that the insurance which the mine owners must carry on their men is much lower, and this is no small item. In addition to this the coal is much better for many purposes, especially for smeltering, than coal from deeper veins, and in the month of August was selling at from two fifty to three dollars a ton.

With the rapid extension of electric transmission lines from central plants in Pittsburg and other places, it is probable that the cost of production will be considerably lessened, because electricity will be used in place of steam. This is due to the fact that a pound of coal burned under stoker-fed boilers and generating electricity by means of turbo generators will yield far more power at the mine than when burned there in inefficient boilers, and the steam then used in inefficient single-expansion hoisting engines or piped hundreds of feet to run pumping engines. This change has been made in the big underground shafts a few miles west of the strip pits just as fast as the transmission lines can be built, and there is no reason to believe that it will not be made here soon.

One tremendous disadvantage of this system of mining is that, unless some radical change is made in the process, these lands, formerly fertile and productive, will, for generations, be absolutely useless as far as agriculture is concerned. An abandoned strip pit looks much like a miniature mountain system with the main trench and the last lateral resembling a canyon. These, however, have an outlet so they become lakes in the spring during the wet weather, and the pools of stagnant water in the late summer breed mosquitoes and ruin the health of the inhabitants for miles around.

Thus it can be seen that a machine which under a correct organization of society would raise the standard of living and shorten the hours of labor of the people as a whole, at the present merely displaces thousands of skilled men and fills their places with a few unskilled laborers working at much lower wages. In addition to this, the people do not get the advantage of the increased efficiency, for the price of coal has only been lowered sufficiently to drive the underground mines out of business. The gains go to swell the dividends of the coal operators.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v18n05-n06-nov-dec-1917-ISR-Harv-gog-ocr.pdf