The second chapter of Goldschmidt’s travel diary sees him describes the streets, and those that populate them, of Moscow decorated for May Day. Comparing the boulevards, their cleanliness, decor and people to Berlin.

‘Moscow in 1920. Chapter II: May Day’ by Dr. Alfons Goldschmidt from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 3 No. 15 October 9, 1920.

May 1.

THERE is no one in the offices. Everyone is engaged in Communist Saturday work, in May First work. For three hours we wait at the Nikolai Station and watch the girls engaged in cleaning up the railroad tracks and cars, smiling as they work. Some of the girls are dressed in velvet and have Russian hoods of good cloth, gloves, and well-kept finger nails. They are removing the debris from the railroad station: not very pleasant work, but it is a pleasure to them. I was watching five girls for about an hour, lovely red-cheeked girls among them. With much puffing they are pushing a car full of refuse. One of them has a red flower in her black hair and a red girdle about her velvet bodice. Another is sweeping the steps and the approach to the station. A fur-piece is thrown around her. Many thoughts came to my mind, such as, for instance, thoughts of the perfume-besprayed Kurfurstendamm in Berlin, of that street of Sodom, that filthy asphalt pavement on which these females ruin their every possibility of life.

The Communist Saturday work, and the Communist Sunday work is rather a work of education and of demonstration than a work of actual performance. But it is nevertheless a labor in common with others and not the uncouth sloth of the Kurfurstendamm of Berlin. And sometimes actual work is accomplished. When I was riding back along the same street I saw hundreds of railway cars adorned with emblems of praise. These emblems lauded the Communist work that had been performed on May First on these cars.

Everybody in Moscow worked on May First, everybody who was not an outspoken lazy dog or a convinced saboteur. Our interpreter, who had gone to town in order to look for persons who might assign us to lodgings, told us he had seen Bukharin sweeping the streets. Lenin swept one of the courts of the Kremlin on May First. I know this is simply for purposes of demonstration; I know this very well. But never before have there been demonstrations of this kind, they are new demonstrations. None of the perfume-besprayed idlers of the Kurfurstendamm in Berlin would ever take a broom in her hand or touch refuse, even with her gloves on. And yet the clean-swept, smooth, sprinkled asphalt of Berlin is a bearer of much corruption. For many hours we sat impatient on the steps of the staircase of the Nikolai Station. A factory delegation marched by, singing “The Red Flag”, the song of death for the revolution, of proletarian death, the song of proud self-sacrifice. I shall say more of this song later. Every child knows it and sings it. The delegation marched by, singing all the time, and the song was marching with the men, led by the waving red flag. One man, at the left of the front row, was beating time with his hands. All were serious.

Autos with red stars on their radiators and red flags at the chauffeur’s seat, rushed by to reach meetings. Everywhere, on the squares, on the gigantic squares of Moscow, in factory yards, in halls, meetings were being held on this day.

The city was flooded with red. Red flags, red bands around white garbed arms, red flags on the walls. Nothing but red. We were rushed in a flying motor-truck to one of the Soviet houses. Troops of children pass by singing, but otherwise the city is silent. For everyone is engaged in the holiday work. The festivities are not to begin till the late afternoon. In the afternoon we paid a visit to the German Council. The German Council is the center for the German prisoners of war; at present it is occupied chiefly in arranging for the home transportation of these prisoners of war. We received an invitation to the May festival of the German Council, to be held in the building of the Third Internationale.

The hall (in which Count Mirbach was murdered) is crowded to the doors. Prisoners of war, together with their wives and guests, brought from remote parts of Russia, and the employes of the German Council, are waiting for the opening of the exercises, the speech of Balabanova, Secretary of the Third Internationale.

A little woman dressed in black, of pleasing figure. Gray strands in her hair, a cane in her hand. She began to speak at once, still breathless from her swift auto trip. Rather empty eyes, directed inward, somewhat faint enthusiasm; she is not a thunderbolt, not a bomb, not a piercing sword. Everything about this woman is heart. She explains the significance of the holiday work, and sings a paean, a song of songs, on socialistic humanity. In the Third Internationale she represents the Italian Party. She loudly praises the readiness of the Italian comrades to aid suffering Austria. The Italian comrades, she says, snatch the Austrian children, neglected wretches, bloodless worms, broken down with hunger, from their misery into the citron warmth of the south. They snatch them to their homes—so ready to aid are they.

There follow dances and symbolic performances. Two “living pictures” represent, one of them, proletarians under the domination of the bourgeoisie, and the second, the same workers after their liberation, with the bourgeoisie lying on the floor in chains.

I saw a dancer of the Grand Ballet, with shoes on her feet, but with bare legs. She was dancing beautifully, and yet it was not a leg-show as in 349 Tauentzienstrasse, in Berlin. It was a dance of bare legs, but not a leg show.

Of the proletkult movement, I observed very little there. Art in Russia is still essentially a means of propaganda. I shall report about it later.

About two o’clock at night, after vehement conversations, we dropped asleep in our beds, overwhelmed with the fatigue of too many impressions.

The Soviet Hotel

Hotels in the European sense of the word do not exist either in Petrograd or in Moscow. To be sure there are porters and cabbies, but no hotel coaches, no hotel commissaires, with the names of the hotels on their caps. If you have been announced from Reval, and if your luck is good, a guest automobile of the Foreign Office or of the Third Internationale may be waiting for you. I had been announced but my luck was bad, for it was May First and on May First nobody pays any attention to us. More important things are under way.

There are guests of the Soviet who have to be treated according to a certain program, with the necessary official apparatus. Others apply to the Foreign Office, whose representatives are very amiable. Of course, it is a Russian amiability; in Russia much is promised and not everything kept. This is due partly to difficulty of organization; at any rate, it never does any harm to keep reminding people, to knock at their doors frequently. If I say to Karakhan, in spite of the fact that I have been assigned to a hotel by the Foreign Office, that people have sometimes been kept waiting for several days in Moscow without any legal domicile and food, he will not be angry, he will simply smile. Every hotel (Soviet house) is under a Commandant. The Commandant has complete control of the hotel, within the outlines of his jurisdiction. He regulates his acts in accordance with the instructions of the Foreign Office, or of the Third Internationale, which also has a fine hotel for its guests. As long as the Commandant has no instructions to entertain a newcomer in the hotel in question, he will do nothing, and it is immaterial to him how the guest may get along. But once he has received his instructions, the guest need have no further care. He sleeps, eats, and drinks in the Soviet house; his laundry is taken care of. For these services the guest pays either nothing or a Liliputian fee. For reasons of formality I had to pay 200 Soviet rubles a day. At the time of my stay in Moscow this meant two or three marks of German money. [*The author probably means marks gold: paper marks are quoted at about 1 1/2 rubles, while gold marks are worth about 100 paper rubles—Editor Soviet Russia.]

But instructions alone are not sufficient. Every stranger must have a pass, a propusk—otherwise he cannot even enter the hotel. The pass is issued by the Foreign Office and is valid for the entire city. For Russia is at war and it would not pay to have people running around unregistered in the country. Even one who only pays a visit to the guest of a hotel must have a pass, for not even Soviet hotels are free from spies. Therefore every visitor, be he a native or a foreigner, must have credentials. He must show these credentials to a guard, who is armed, and who would surely not hesitate to arrest an interloper who would come without credentials. The most spacious Soviet houses of Moscow are the Metropole, the National, and the Savoy. They are not called hotels, but the First Soviet House, the Second Soviet House, etc. The lobby of such a “house” is still the old hotel lobby, but it has nothing else about it that would remind you of a great metropolitan lobby. The padded arm chairs, on which women in rustling silks and smugly-groomed officers reclined by the side of provincial merchants, tourists, etc., have disappeared. The mirrors are covered or at least dimmed. One big stair-case mirror in the Metropole still shows a bullet-hole as a vestige of the struggle for power. The bustling porter, with his staff of flunkeys, is gone; the stands for the sale of trinkets, chocolates, and newspapers, are but a memory, and no grand duke calls to rent a suite of rooms. Everything proceeds in a sober and businesslike way. To compensate for this you are not fleeced. You pay no tips. Your room is clean; your food is scanty but good (much kasha, a few potatoes and little meat, much tea, sufficient bread, a little butter).

Of course, the rooms of the Soviet houses are still provided with all their past splendors. These splendors may be somewhat dimmed; the Empire sofas, the plush chairs, the rococco tables, are losing their brightness, even as are the bourgeoisie. There has been no time for repairs, nor have they been needed. The guest must content himself. And he may well do so; The Commandants, the chambermaids, the waiters (all Government employes) are pleasant and efficient.

Some hotels have telephones in almost all rooms. Central will connect you quickly. As every guest has important business, as hardly anyone is loafing in Moscow, the telephone girls at the centrals are more than busy. The service is not worse than in Berlin.

Most animation centers about the Metropole, in which many of the higher Soviet officials live. As the Foreign Office is housed in an annex of the Metropole, most of the Foreign Office officials live in this Soviet house. Often their wives and children live with them and their entire domestic life is passed in this building. Before the Revolution, the Metropole was the most aristocratic hotel in Moscow, and grand dukes celebrated their orgies here. There are still Trimalchian recollections, orgiastic reverberations; but most of the things are being devoted to better purposes now. I am told, for instance, that in one palace of pious pleasure, profiteers are now being confined in jail for their offenses.

The red leather alcoves of the Metropole, which form a rotunda about the former concert hall, with little projecting balconies and secretive doors, are today occupied by Soviet officials. The concert hall is the meeting place of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Republic. Speakers speak from the platform of the concert hall, on which the managers of the meetings are sitting. In place of a gypsy violinist, Kalinin now holds the baton. He is the chairman of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee. He directs the proceedings, faced by a picture of Karl Marx, whose gnarled bust has been placed in a niche of this hall.

Meals are, to be sure, equitably rationed in the hotels, but the foods are not prepared uniformly.

Cuisine is still an important feature. If guests arrive who must be placated, who are to be treated realpolitically, guests whose idiosyncrasies must be observed, there is a marked improvement in their rations. For instance, there was a ruler of a semi-Asiatic state that had attached itself to Soviet Russia. At Moscow he was surrounded not with hotel splendors, but certainly with all hotel comforts, such as were not offered to other guests. There was a hum of energetic activity around him. The English Mission, which was in Moscow in May, 1920, was very well entertained and served. They had salmon, ham, much meat, splendid autos, attaches, and the like. We observe the following law: those who are comrades in thought and action are treated as if they were really inhabitants of Russia, as real Russians; people whose ideals are not completely reliable are treated with kid gloves. For instance, if Scheidemann should come to Moscow, he would probably be received as was that semi-Asiatic prince. Of course the truth would not be withheld from him. Lenin told the English trade union leaders a number of things that were far from pleasing to them. But Scheidemann might eat at Moscow as well as with Sklarz in Berlin. Therefore, Philip, on to Moscow, and take Fritz with you! He will not get thinner there. [*Fritz probably means Friedrich Ebert, President of the German Republic. Ed.]

The head of our delegation was assigned, together with myself and others, to a splendid villa. To a villa that had been the residence of a Consul before the Revolution, and contained large rooms and halls, white tiled bathrooms, dreadful paintings, a billiard room, a terrace and syringa grounds, of an unspeakable spring sweetness. There was gathered here an international company of journalists; Japanese, Chinese, English, Americans, Frenchmen, Italians, not to mention representatives of Korea, Bokhara (they ran off at the appearance of pork), Tatars, a veritable Babel. Miss Harrison also was there. I cannot omit this fact, for everybody knows her and she knows everybody else. She said to me: I know Theodore Wolff. Miss Harrison is a courageous woman. She travels through all the editorial offices and revolutions for her news syndicate and she knows even Theodore Wolff.

Streets and Squares

Moscow is in need of repairs. Every European capital, now that the war is over, is in need of repairs. But Russia is still in the midst of the war, is still obliged to wage war; for no peace is given to Russia.

The railway stations are in need of repairs; so is the pavement, so are the facades of the houses; everything needs repair. The pavements of Moscow are said to have been no delight to the gentle spirit even before the war. There is little asphalt and no lack of cobblestones. Cobblestones lacking symmetry, cobblestones lacking a sense of order, cobblestones possessed with curiosity, sticking out their heads higher than the rest. There are hills and dales in the pavement. Therefore everyone who makes a pilgrimage to Moscow must take with him at least two pairs of well-soled boots. The trolley cars (“200 of them were in operation at the time of my visit) are overcrowded; most of the automobiles are at the front, and there are not too many cabs. So you have to walk, and you walk not only on the splendid smooth boulevards, on the asphalt of the show streets, but also on the block pavement. Former ministers of the German Republic, who have the intention to visit Moscow, and who are accustomed to living on a splendid scale, should perhaps take three pairs of well-soled shoes with them, as they will always step on several cobblestones at the same time. But they may leave their tuxedos at home. Tuxedos are not needed at Moscow. You can pay a visit even to Lenin in an ordinary business suit. Your trousers may be torn, provided your soul be clean. It is necessary to impart this information concerning clothing, for I was asked immediately on my return as to wardrobe needs, and I herewith give the information for the benefit of everyone who may read my book. I may even go so far as to betray the fact that several “high” Soviet officials and revolutionary leaders are walking about with torn pants. For instance Bukharin is no Petronius, God knows, and Klinger, Secretary of the Third Internationale, wears clothes that are more threadbare than the platforms of the parties in the German Reichstag. He was not at all comme il faut when I spoke to him. But the streets of Moscow are clean. They are often a little friable, like those of Petrograd, and people with an instinct for niveau might wish they were more uniform, but they are clean nevertheless. Last winter the sewerage system was frozen up and things were pretty bad. But when I was there the water supply was functioning well, the gutters had been washed clean, and there was no odor of garbage.

Of course the streets are not splendid metropolitan streets with bourgeois decorations. Most of the shops, as in Petrograd, are closed or even boarded up. The little stores, in which goods are still being sold, offer for sale trinkets, gewgaws. little mechanical devices, particularly electric, soda water in bottles, soaps, and things of the sort. Occasionally you catch sight of Soviet shops, or even Soviet stores, in which products are sold that have been rationed by the authorities (the Provisioning Commissariat) and may not be sold above maximum prices. There you will find shirts, socks, hats, also utensils at very low prices. To obtain even these objects is still difficult as industrial production in Russia is almost at a standstill. It will not be possible to carry out the rationing system until a sufficient supply of commodities is on hand.

Many houses in Moscow are weather-beaten, and many are empty, and yet there is an acute shortage of dwellings; but this also will be changed for the better before long. A country waging war cannot work as does one at peace. Particularly the big cities suffer from the war. They are the chief stumbling blocks in all economic and human crises.

The streets of Moscow, particularly the main streets, are animated. At certain times of the day, for instance, about ten in the morning and about 4.30 in the afternoon they are very animated. For these are the hours for beginning and ending work. The streets at these hours are alive with people, there is a general pushing and shoving, a general rush, an extraordinary bustle in the streets. But at other hours also, and in the evening after the closing of the theatres, the streets are also active. The boulevards are then more than filled.

Moscow too is a city of workers. Externally not quite so much so as Petrograd. But the proletariat rules the city. You have this impression as soon as you enter Moscow. There is still much elegance in Moscow and yet the proletariat rules. This is essentially the stamp of the Moscow street. Every possible social layer may crawl about on the street, and yet the proletariat is dominant. It dominates the street with its police, it dominates the street with its labor regulations. The street of luxury, of amusement, of bazaars exists no more; it is now a labor street and a street of relaxation. There is not much work being done yet; there is by no means enough work done in Moscow; and yet Moscow is already a city of workers.

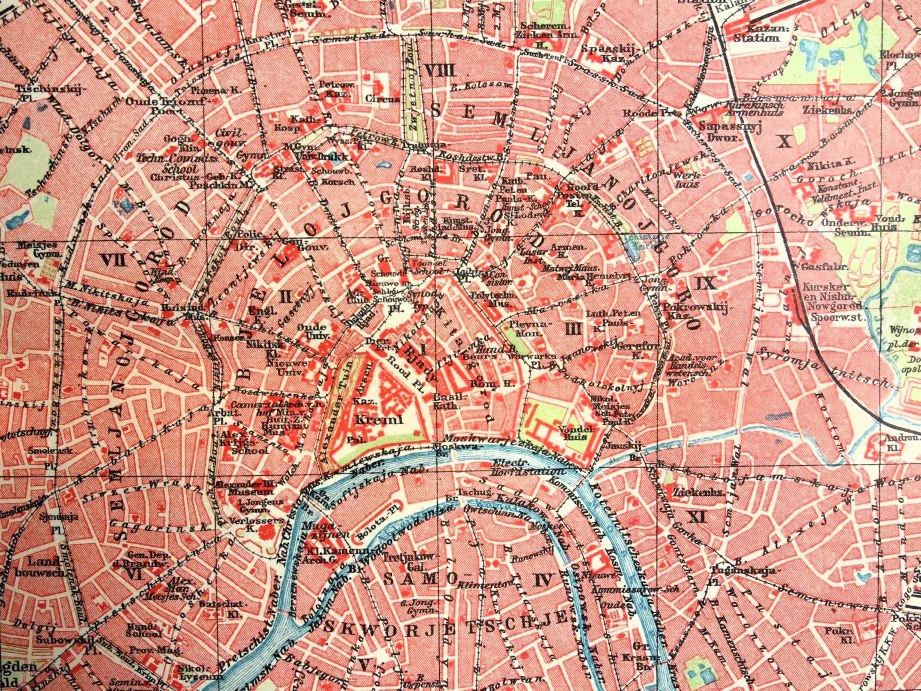

Splendid are the squares of Moscow. The finest square of Moscow is that of the Kremlin. It is half a drill ground, half a market place, or half a parade ground and half an amusement place, or half a business market and half a place for show. The high Kremlin wall on one side, with its towers and its still preserved miracles, the former gigantic bazaars [*The Targovye Ryady, an arcade consisting of small shops formerly selling luxuries, souvenirs and other objects. Ed.] a modern Asia, at present the Commissariat of Labor, on the other side. At its entrance, the wonderful image of the Iberian Madonna, which is still entreated for miracles, and at its exit the finest architectural splendor of the world, the Church of St. Basil. Along the Kremlin wall there are the graves in which the heroes of the Revolution rest, covered with red ribbon wreaths. The Kremlin wall is covered with shining revolutionary plastic art, from which great tracts of red issue forth and spread in all directions. It is a splendid square. It is broad—broad as the Russian soul. So broad that the giant map of the Polish front which has been set up there, looks like a little white speck. It is a splendid square for red parades, for troop reviews, for militia drills, for burning addresses, for reminiscences of struggle. While helmeted warriors are seen climbing the Kremlin walls with carved swords between their clenched teeth, the marks of machine-gun bullets still bear witness of the struggle of the proletariat against capital.

Red troops march around the square at the Kitaisky Wall (the Chinese Wall), singing as they go, red flags attached to their guns. Their knees not rigidly straight, their attitude a proud insolence, they sing the song of the Red Flag as they pass under this mighty wall, on which armies might defend themselves; they pass this product of an infinite brick-like patience, built by ants. Thus the walls were built that the Jews once had to erect in Egypt. And much sweat has been cemented in this wall.

Splendid is the Theatre Square, the square in front of the Great Theatre. Here the official life and the pleasure life of Moscow center. It is the stone rosette of Moscow, enameled with verdure, and flowers, and always with many people sitting on the benches. Across this square automobiles are constantly dashing, while cabs pick their zigzag course and troops are marching, troops of children, of scholars, or soldiers. I have spent hours on this square, the broad artery of Moscow, the compass-rose of Moscow, with its rays directed towards all the sections of the city. Here I watched the sellers of mineral water, the flying tradesmen, beggars, arguing citizens, elegant ladies. There is nothing finer in the world than the broad squares of Moscow. It is a very ancient city, with its squares. The squares have seen storms and have been in complacent repose, and such is their repose now, after the storm of the November Revolution.

Splendid are the squares of Moscow. Red rimmed, green rimmed, flooded with broad daylight, dotted with leafy shade, with all the animation of the city. By the squares of Moscow you can see that the city is still living, that it cannot die. A great city cannot die in three years. Rome is eternal and Moscow is immortal.

The Boulevards

Is there still a terroristic dictatorship in Moscow? No there is not a terroristic dictatorship in Moscow. If there were a terroristic dictatorship in Moscow, there would be no May boulevard with the merry spring life of May, 1920. A green recreation thoroughfare, interrupted by squares and intersections, the Moscow Boulevard encircles the entire inner city. It was once better groomed than now; you might say it was combed and washed. But its streets are still there and the brown road still runs round the inner city, the benches remain, the music-stands, and the refreshment-booths. The little lakes still twinkle and if there are few incandescent lights, in order that the electric current may be saved, the life on the boulevards is still incandescent. About 10 o’clock at night (Moscow time) life becomes active in this region, but not as active as before the Revolution. There is not the hectic animation, the flashing bustle, the blinding brilliance, the carnival gaiety, the Cossack officers ready to pounce on their booty, the shining dowagers in their rolling chairs, the pearl-covered corruption of before the Revolution. There is still enough of the bourgeois, enough of vulgarity, enough of profiteering and speculation, and other vermin. But, as the Moscow street is already a labor street, so the Moscow Boulevard has become the recreation thoroughfare of the proletariat. Often you see no proletariat on this recreation street, and yet the street is a promenade for the proletariat, for the proletariat now tolerates the jobbers, speculators, the ear-pendants. Formerly the ear-pendants, the jobbers and speculators, tolerated the proletariat.

Along this Boulevard, this long, gently-winding recreation thoroughfare, no bomb explodes, no gun is fired, no dictatorial glance is seen to flash. Everything is very peaceful. Couples are out walking, red soldiers ambling along, people coming from work across the promenade. There is joking, problems are illuminated, secret deals are whispered, and women are loved. The citizen of Moscow walks, sits and promenades, a free man, along this brown and green girdle, singly and in pairs, serious or glad, full of care or. with breast held high.

There is no horse play. In no city of the world have I seen so much dignified pleasure displayed along the promenades. In no city of the world (and I have seen many cities) have I seen women so modest (romantically speaking). There are no professional prostitutes in Russia any longer. Before the Revolution statistics show (statistics were particularly unreliable in Russia) 160,000 prostitutes in the streets of Moscow. If one is still found, she is put into a labor battalion. The elimination of professional prostitutes, in fact their immediate elimination, assigning them to a place in working society, is a self-evident demand of Socialism. It is a human demand, an anti-capitalistic demand, even a sanitary demand. Venereal diseases (read the program of the Bolsheviki) are among the social diseases, together with tuberculosis and alcoholism. The program of the Communist Party of Russia adopted at the Eighth Party Congress, under the caption “Protection of Public Health”, demands that social diseases (tuberculosis, venereal diseases, alcoholism), be combatted.

Love has not ceased to live in Russia. It is eternal as is also folly. But the communization of women by means of prostitution has ceased. Of course this does not mean that “venal love” has given up the ghost. Things do not move as fast as that. Love is still bought and sold in Russia and in Moscow, but the process of buying and selling love is being wiped out. The process is already moribund and will shortly die. Habitual prostitutes have already been eliminated; secret prostitutes, such as those that are married cannot be eliminated within three years. There is still much distress in Moscow and distress breaks the pride of women, and therefore there is still a social plague of love. Women complained to me in Moscow about this. They loudly and warmly praised the great elimination that had been accomplished by the Soviet Government and they wished a swift alleviation of the distress of life so that the social plague of love might be done away with.

If there still exists a communization of women as was formerly the case you would notice it on the boulevards, for it was on the Theatre Square and on the boulevards that the communized women sold themselves, but this is a thing of the past. Even one who would love to condemn and hate every act of the Soviet Government must laud this act, even though he be a merely liberal humanity whiner. Of course this act will ruin his case, but it is an act that is on his own program. The trade in women has ceased, the slavery of lust has died out, the pride of women is rising. I shall only say what I actually saw, no more and no less. I must repeat that this is my intention, for otherwise you may think that I am merely a propagandist.

The refreshment booth with the garden tables and garden chairs in front of them still have little buffets inside. People told me about the buffets during peace and war times. They had been wonderful buffets of delicacies with Moscow candies, cordials in a hundred colors, and an elegant crowd seated round them. Of course this is all past. Very courageous speculators, who do not fear the combat of the Extraordinary Commission against smuggling, openly sell mocca and delicate cream tarts. Their customers are bespangled remnants of the bourgeoisie, women with pearl ornaments, fabulous footwear and flashing rings on their manicured fingers. They sit there with their cavaliers (there are cavaliers still in Moscow) and sip, (elegant ladies as is well known, do not drink, as proletarians do, they sip) mocca and perhaps an ice. It may cost a few thousand rubles, but there is more where that came from. Nichevo! They sell a few things to a jobber, escape work, and sip!

I should like to give a hint to those who are seeking pleasure. If one of my readers should arrive at Moscow during the summer, the hot Moscow summer, far from the sea, the asphalt dissolving summer, the perspiring summer, let him carry a thermos bottle of cold tea with him, but in the evening let him eat or drink the thick milk, ice-cold thick milk, which he can get in the buffets of the boulevard’s booths. It is delicious. The price is only 125 rubles per glass. But he will have to hurry. He must reach Moscow before the end of the summer for otherwise the price will be much higher. It will be double, triple, even much higher. Of course that will make no difference, but it will shock the quantity idiots. The boulevard does not become empty until about on o’clock at night (Moscow summer time). But every night unless there is a storm, it is filled with a dignified, jovial humanity, not without a few centers of decay and with some who are infected, but nevertheless a street of the future, leading to a more honest civilization.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v3n15-oct-09-1920-soviet-russia.pdf