Some remarkable jail memories–such as prisoners counting the days as Bolshevik power passed the seventy of the Communards–by the wobbly agitator, and founding Communist. Harrison George, one of hundreds of I.W.W. figures arrested in the 1917 sweep,was first locked up in Cook County and later in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary for opposition to the First World War. Serving more time than most others, he wrote a number of articles about prison life on his release, perhaps to work through the experience. Here he speaks to the importance of outside news to the political prisoner, the papers the read–sometimes smuggled–and the reaction of comrades to events in the movement.

‘The Can-Opener’ by Harrison George from The Liberator. Vol. 7 No. 1. January, 1924.

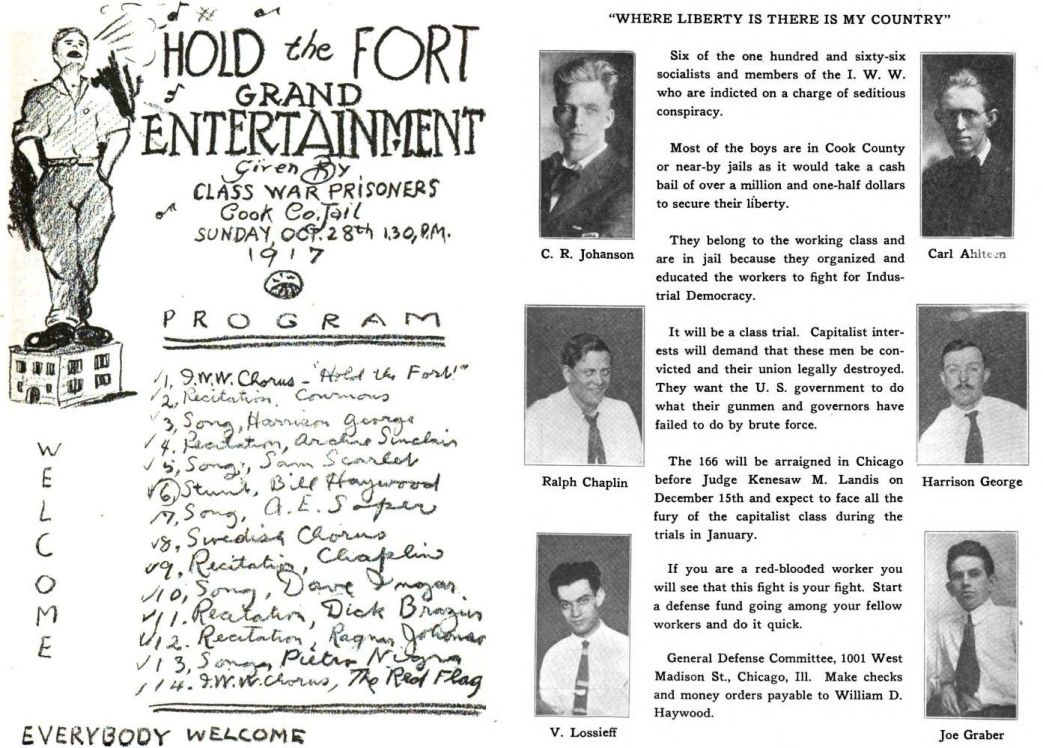

WHEN I was in Cell 45 of the “old jail” in 1917, the Russians, Vladimir Lossieff, Joe Graber and Leo Laukki, concessionaire who went the rounds of the galleries shouting nasally–“Coffee, sandwiches, pie and doughnuts,” was the herald who brought us tidings of how things were going with the Red Guards along the Neva. He was the authorized distributor of news, hawking the Chicago Tribune and the Daily News from cell to cell at a nickel a shot.

These papers were the best we could get that winter in the old “Cook County Can,” and many of us Wobblies had to read them second-hand, passed along by the fellows who could afford the luxury of buying. The New York Call, then prospering mightily under persecution for its militant pacifism of early war days, was as impossible to us as were a decent meal and a clean bed.

John Reed’s dispatches to the Daily News under a Petrograd date-line were meat and drink to those of us who comprehended the Bolshevik uprising in its historical significance. The evening “zoup”–as the runner called the official fare, stunk of “Bubbly Creek,” and the “duffers” of “war-bread” made from mouldy grain were beyond good and evil and human digestion. The cook and the concessionaire were in conspiracy but, being broke, I scorned the aroma of sandwiches and coffee and supped on Russian Revolution in my dark little cell not twenty feet from the one in which Louis Ling blew off his head in the year 1887. The daily papers had to suffice.

The I.W.W. papers were either suppressed or devoted mainly to matters of defense of members undergoing prosecution. The socialist press at that time was, as usual and as yet, colorless where not traitorous. The “Chicago Socialist,” a party organ, said in its issue of December 8th, 1917:

“Editorially the ‘Eye Opener’ (the national party organ) has withheld expressing its opinions concerning the stand taken by the Bolsheviki. We feel that their rule is but a transitory stage in the progress of the Russian nation toward a stable and permanent government. The problem, we hope, will finally be solved by a coalition Socialist government representing all factions of the Socialist movement in Russia.”

To those jailed Wobblies who swore by the new workers’ republic then upheld shakily but fearlessly on the points of Red Guard bayonets, the official socialist papers of this country were pretty poor stuff. For the diversion, we Wobblies in the “old jail” got up, laboriously, a hand-made paper of our own, called “The Can-Opener.”

Not all of the Wobblies, of course, who milled around the bull-pen of the Cook County Jail that winter, understood–or were even interested–in what the very existence of the Russian Red Guard meant to world history. Some scowled, although sympathetically, feeling a little hurt that the I.W.W.’s recipe for revolution–the general strike, lost its monopoly of prominence amid the thunder of the guns. A few were non-committal. Others dismissed the subject as “a mere adventure.” But, over in a corner, the debated with me the advent of a new epoch if–terrible if!–the Bolsheviki could hold on to power longer than did the Paris Commune, seventy days…

Seventy days came and went. Months came and went, and we Wobblies went to Leavenworth after one of Judge Landis’ “fair and impartial trials”. Bourgeois dictatorship remained in America and the proletarian dictatorship remained in Russia, though Russia’s workers fought continuous civil war at home and foreign invaders on Russian soil. We in Leavenworth watched the battle anxiously through the field-glass of the newspapers published by the bourgeois dictatorship of America. Their complaint that the Bolsheviks had suppressed the capitalist newspapers of Russia tickled us Wobblies, who had seen our own papers suppressed while the bourgeois newspapers shrieked to high heaven for our blood.

We read, also, the stirring news from Germany, and how the proletariat fought for possession of newspaper offices and printing plants. From behind bars we beheld the heroic Spartacus group fight and fall. Never did the walls of Leavenworth seem so maddeningly in the way as when I read in the Kansas City Star of the murder of Liebknecht and Luxembourg…Against Ebert and Noske–against all the Eberts and Noskes of the world I flamed with anger, and I still wonder at the temerity of those “revolutionaries” who protested to Soviet Russia at even the imprisonment of counter-revolutionary S.R. and anarchist conspirators, but who were silent at the butcheries of Noske and Ebert! Will they again wail for clemency when these murderers are being tried for their crimes before a proletarian court in Germany…?

We lived on newspapers at Leavenworth, and labor papers, always scarce, were literally read to pieces. The Union Record of Seattle held the stage for a time, especially during the Centralia affair–when the Wobblies shot it out with the Legionaires and lumber trust hirelings who tried once too often to raid Wobblie Hall. But the Record turned yellow later, while the Butte Bulletin, edited by Bill Dunne, was the prize of all papers that came to our hands.

Wobblie papers were forbidden entry by the warden, but some way or another–just how I must not reveal–one or two copies got into the cell-houses, where they were read secretly and hidden under our shirts. But the Wobblie papers were falling sick with the phobia that still persists. They were beginning to talk against Russia, advocated “industrial” communism (as though there could be communism with adjectives!), and basely attacked the Communists on trial in Chicago as the Socialist Labor Party papers had attacked us during our trial before Landis. Wobblie papers were sickening under control of Sandgren–who is now writing a big book to refute Marx! and of Harold Lord Varney, spy and renegade, who is now lecturing “against the reds” for the Constitutional League of Detroit! The present I.W.W. officialdom still slavishly follows the precedent set by Sandgren and Varney. I.W.W. papers are still all against dictatorships and all for “industrial” communism. Unfortunately dictatorships are a part of social evolution…! Now that a great Communist daily–The Daily Worker–is due soon to begin mobilizing the scattered battalions of labor for a united front for not only the release of class war prisoners but also to sound the trumpet for battle on all fronts, political and industrial, against capitalist exploitation, surely the message of unity, audacity, victory will reach many a listening ear behind prison walls from Mooney and the Wobblies at San Quentin, the Centralia victims at Walla Walla, and the boys at Leavenworth to the cells at Dedham and Charlestown, Massachusetts, where lie Sacco and Vanzetti under sentence of death.

While the Butte Bulletin and the Liberator were the most popular publications at Leavenworth, the left-wing papers began to excite an interest. I recall with what joy I read in The Toiler, then in Cleveland, the first manifesto of the Communist International calling internationalism to arise from the betrayal and ruin of the Second International. When the left wing, in August 1919, gathered at Chicago to be thrown out of the Socialist Party, I wrote from Leavenworth my endorsement of any party formed on the basis of the Moscow Manifesto and the Communist Manifesto of 1848. The press which brought Bolshevism to America began to grow.

How class war prisoners watch the news! Every strike, every demonstration is picked out from among advertising and sports where a capitalist editor may stick it, and made the subject of conversation and comment. How closely we watched the firing line of the Red Army may be illustrated by the remark one Wobblie made to the effect that some of us in Leavenworth knew more than did Trotsky about what the Red Army was doing! How cheerful was the news of the hope of all interventionists, Admiral Kolchak, being impaled on the bayonets of his own soldiers…! And the birth of the Federated Press in November 1919 presaged a time when we might get labor news from other and less prejudiced sources than the capitalist press.

In prison every event is magnified in importance. Class war prisoners do not feel imprisonment so much if they see outside the lines of labor advancing in battle array.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1924/01/v7n01-w69-jan-1924-liberator-hr.pdf