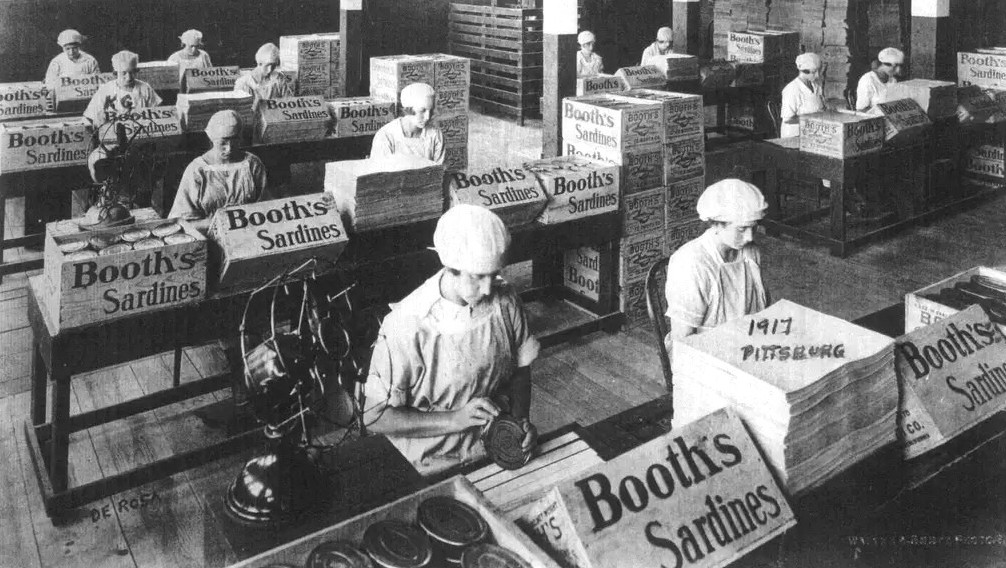

An Italian-speaking organizer from the I.W.W.’s Fishermen’s Industrial Union reports on a successful strike in Pittsburg, California.

‘California Fishermen Strike and Win’ by S. Martignoni from Solidarity. Vol. 7 No. 353. October 14, 1916.

Women Take Leading Part in Fight That Brings Fish Merchants to Strikers’ Terms

Pittsburg, Calif. On the 18th of June we commenced to organize the fishermen on the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers. We started with 30 members. As they have been organized by the A. F. of L. four different times and failed, the officials having exploited them and sold them out during strikes so they say, there was some difficulty in showing them the necessity of organisation, and explaining the difference between the two. They were very dubious (I did not blame them) especially the Italians, who are in the majority and whom I was sent to organize. But with patience and perseverance we succeeded in lining up the majority.

On the 25th of August, first day of the fall season, the fish barons cut the price of salmon from 5c per pound (price fixed by the union) to 4c. It has been the custom of the fish barons to cut the price down to as low as one and one-half cents a pound in the fall. As the fishermen mostly own their own outfits, the fish magnates and small buyers and their agents who generally furnish them with the necessary equipment at exorbitant prices, keep the poor fishermen continually in debt. When they talk strike, the buyers threaten to take their outfits away. Not being educated along the lines of industrial unionism, they have always bent their n to the yoke and submitted to the bidding of their masters.

But things have changed this time. As soon as the price of fish went down to 4 cents they struck and stood solid as the Rock of Gibraltar. They knew if they lost the strike the union would break up and they were doomed. The magnates and their agents tried every means to break the strike, but no desertions occurred.

The majority stored their nets in their homes. Although hunger was at their doors and the children began to cry for bread (the majority have big families) the women encouraged the fishermen to stand solid and threatened them should they dare go out scabbing. These brave women understood better than their husbands fathers and brothers, the meaning of a lost battle. They feel more the misery than the men do.

After 18 days the barons wanted to arbitrate for four, and one-half cents on the drift and 5 cents delivered at the place of business. This the fishermen flatly refused, and next day the bosses granted our demands.

After the boys went out fishing, the fish dealers tried their last scheme they sent for L. Parenti (who was here directing the strike) and S. Trapani, president of the American Fish Co., spoke, saying: “The fish is not good, we can’t ship it, we can’t cure it; we have no place to put it. It is only good for the canneries and has its value for that purpose. We can only pay two and one-half cents a pound.” We asked him if he could have found a place to put it at two and one-half cents a pound, even if he could not ship or cure it. He answered: “Yes.” That let the cat out of the bag, and I told him it was only a trick to cut the price. He got up and went out.

Foreseeing possible failure of this trick, before they met us even, they sent for the sheriff from Martinez.

The fisher women, hearing about this cut of two and one-half cents, gathered around the canneries and went after the fish barons with rocks and other things too numerous to mention. When Fellow Worker Parenti and I met the women, we told them to be quiet and go home. One said: “We will start a revolution here, and who are you?” We told them. “Well, aren’t we right?” She went on to tell how these parasites had kept them in poverty all their lives. In the evening, Trapani and his bunch of buyers said the fish were better and they paid the price, 5 cents.

During this strike, we had 15 men in jail, 7 Greeks and 8 Americans, charged with petty larceny and assault. The Greeks, who live at Vallejo, went out patrolling the river and met a union Greek from San Francisco fishing. The boys took 850 fish away from him and gave it to the orphans and poor of Vallejo. For this he had them arrested. We had a lawyer, but the judge fined them $5 each, after being in jail 10 days. The days before the strike was settled, Some Portuguese went out fishing and some of our boys went to stop them; as a result 8 were arrested. Six were acquitted for lack of evidence, and H.C. Adams and Carl Boll were held on $25 bail, which was furnished. The scab who swore out the warrant was illiterate and the law says that such a person must have two witnesses with their signatures, and he had only one. Our fellow workers are out pending new information.

As a result of this strike, the fishermen who were in doubt before, are lining up as fast as they can. We are making a strenuous effort to organize the Alaska fishermen, who are inclined to join.

S. MARTIGNONI, Secy, Fishermen’s Industrial Union 449.

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1916/v7-w353-oct-14-1916-solidarity.pdf