At the center of capital’s expansion, and therefore at the center of the capitalist’s worldview, is the “annihilation of space by time”. Part of a series from Marxist historian and economist Mikhail Pavlovitch, then living in Parisian exile, below the truly awesome annihilation that the completion of the Canal meant for U.S. capital as it shifted the world economy to the Pacific and undermined all other imperialists in the Western Hemisphere.

‘The Panama Canal: Its Economic Significance’ by Mikhail Pavlovitch from New Review. Vol. 1 No. 8. February 22, 1913.

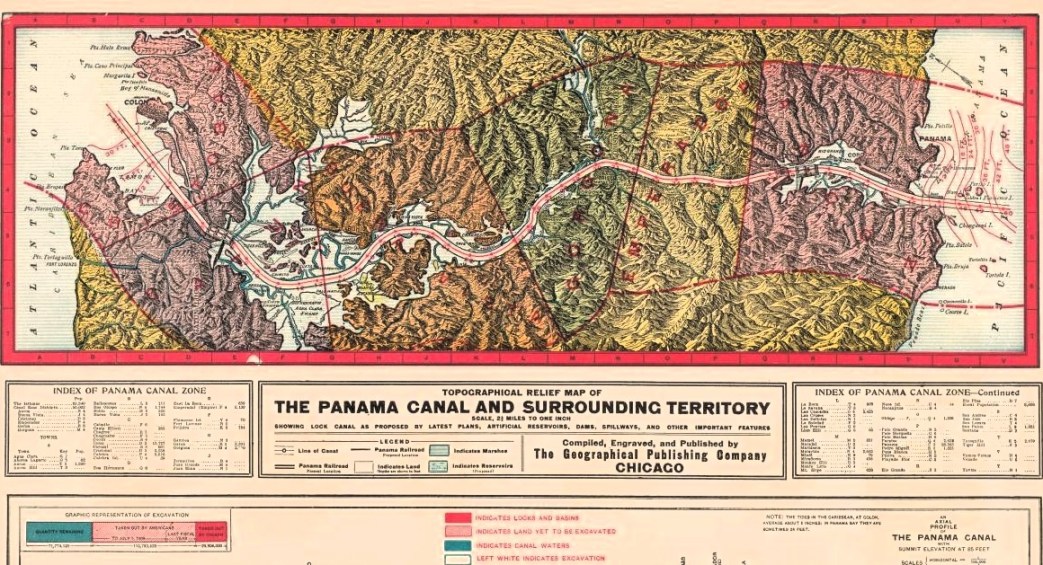

When the Panama Canal is finished, a new world route, almost parallel with the equator, will girdle the globe. What will be its influence on international commerce and how will the relations of Europe and America, struggling for possession of the great Asiatic market, be affected? Despite assertions that the canal is primarily of strategic importance, it is clear that this monument of engineering skill, the greatest known in history, has as its basic purpose the opening of the markets of the Pacific. The United States undertook the task of building the canal to gain supremacy in the ant hills of the yellow world. The whole problem consists in unloading, at the lowest possible price, the products of American factories on the swarming millions who people the coasts of the Pacific, and for this the shortest and therefore cheapest route is necessary. Let us see how far the Panama Canal solves this question, in what degree it increases the chances of the United States gaining supremacy in the Pacific.

According to the latest data, the foreign commerce of the Celestial Empire with the principal countries, in 1910, amounted to the following:

Imports into China–Exports from China

Great Britain £9,552,267–£2,518,133

Hong Kong 23,085,393–14,637,956

British India 5,918,334–610,520

United States 3,338,890–4,347,220

Germany 2,876,856–1,796,294

France 371,719–5,227,830

Russia and Siberia 2,160,460–6,188,105

Japan 10,334,017–8,294,331

As may be seen from these figures the United States by no means occupies first place in the commercial relations of China.

The lion’s share in exports, especially, belongs to Great Britain.

Turning to other Asiatic markets we shall find that in 1910 there were imported into Japan manufactured goods to the value of 94,700,911 yen from Great Britain; 106,361,497 yen from British India, and but 54,699,166 yen from the United States. [* A yen is equal to about 50 cents.]

As for India, the Asiatic market next in importance to China, her commerce with the United States is insignificant as yet, the imports amounting to but 1.5% of the total. They lag behind those of Germany, Belgium, Austria-Hungary and other countries.

But it is not only in the Asiatic markets that Europe, chiefly Great Britain, is ahead of America. The same is true of all the countries washed by the waters of the Pacific Ocean. Thus the imports from Great Britain into Australia in 1910-1911 amounted to £36,646,441 and from the United States only £6,449,829, about one-sixth of the English imports. But what is of especial significance, even South America has remained chiefly Europe’s customer; England, Germany and France all ranking ahead of the United States in selling there. This has been especially humiliating to American capitalists with their motto of “America for the Americans.” The average share of the United States in the foreign commerce of South American countries is between ten and fifteen per cent. In general it may be said that despite the wonderful advance of her industry in the last decades and despite her advantageous geographical position, the United States has with difficulty kept up to the struggle in the Pacific against Japan, Germany, and particularly Great Britain, which still retains the world’s commercial supremacy. The reason for all this, which seems incomprehensible at first glance, lies in the advantage which the Suez Canal has heretofore given to the European powers in the struggle for supremacy in the Pacific. To reach the coasts of China or Japan, American ships have to traverse about 2,700 miles more than English or German ships. To compete with Europe in Pacific waters the United States has to surmount the colossal advantage of a shorter route which the Suez Canal gives to Europe. In the struggle for industrial supremacy in the Pacific Ocean, the Panama Canal will be a mighty weapon in the hands of the United States. If we are to believe American scholars and writers, the Atlantic period of the world’s history is already nearing its end. The centre of gravity in economic life is being rapidly transferred to the Pacific Ocean, hitherto lying in the backyard of history. To quote Roosevelt, the “Pacific Ocean era” is beginning now. And dominion over the Pacific, owing to the Panama Canal, must inevitably belong to the United States.

To begin with, let us see what effect the opening of the canal will have on the struggle of Europe for the Pacific markets.

It will to a great degree allay the fears of the European pessimists and dispel the illusions of the American optimists. For under no circumstances can the Panama Canal destroy the importance of the Suez route, which will remain for all Europe the shortest way to the Asiatic and Australian coasts of the Pacific Ocean. The Panama Canal will not facilitate commerce between Europe and Asia, and from that point of view will be useless to Europe. The route from Liverpool, Havre, Hamburg, and Antwerp to the coasts of the Far East is shorter by thousands of miles by way of the Suez Canal. The following table gives an idea of the advantages of the Suez route (in nautical miles of 6,080 feet):

Via Suez Canal–Via Panama Canal–Difference in favor of Suez Canal

London-Hong Kong 9,700—14,300–4,600

London-Shanghai 10,600–13,700–3,100

London-Yokohama 10,920–12,645–1,725

As for Marseilles, Genoa, Trieste, Naples and other ports lying on the Mediterranean, as well as the Russian ports on the Black Sea, the Suez route to the Asiatic coasts is also better for them. A difference of 1,000 miles of sea route represents, in the case of a 5,000-ton vessel, a saving of 500 tons of coal. On the other hand, the distance between European and Australian ports via Suez is longer than via Panama, as may be seen from the following (nautical miles):

Suez route–Panama route– Difference in favor of Suez route

London-Melbourne 11,728–12,728—1,000

London-Sydney 12,192–12,377–185

Southampton-Melbourne 10,800–12,400—1,600

As regards New Zealand, the Panama route is somewhat shorter than that of Suez, but the latter being rich in coaling stations and markets for the sale of goods, the advantages will remain on its side for a long time to come. Thus it is clear that the Suez route will remain as formerly the great European commercial route, and along with the development of industry and international relations its role as the greatest world artery will also increase in importance. The economic revival of the Balkan peninsula will also increase the value of the Suez Canal to an extraordinary degree.

Now then, the Panama Canal will in no way shorten the journey from the great European ports to those of Asia. But it will bring about a revolution in commerce between the United States and the Pacific coasts of Asia, Australia and South America, as can be seen from these figures (in nautical miles):

Distance from New York Via Suez Canal–Via Panama Canal–Difference in favor of Panama route

To Hong Kong 11,700–11,000—700

Shanghai 12,600–10,400–2,200

Yokohama 13,800–9,300–4,500

Valparaiso 9,700–5,400–4,300

Sydney 12,900–9,800–3,100

San Francisco 14,800–4,700–10,100

Thus the Panama Canal will shorten by thousands of miles the distance between New York and the most important commercial ports of the Pacific. Though offering little to Europe, this route will give much to the United States and will tip the scales in favor of the latter. Many markets of China, Japan, British India, Australia, and South America, heretofore lying nearer to Europe, will in 1914 find themselves much nearer to New York and other great American cities, as will be seen from the following table (nautical miles):

From the Channel via Suez–From New York via Panama—Difference in favor of Panama

To Shanghai 10,600–10,400—200

Yokohama 11,000–9,300–1,700

Valparaiso 8,400–5,400–3,000

Sydney 13,100–9,800–3,300

San Francisco 8,000–4,700–3,300

With the opening of the Panama Canal the United States will at once be able to compete victoriously with Europe in all the markets of Japan and in the principal markets of China and Australia. England’s commercial supremacy heretofore unquestioned, is therefore seriously threatened. Soon all the talk about the “German menace” will be forgotten and the new cry of an “American menace” will resound over all England.

But the opening of the new route will be of the greatest moment to the Pacific coast of South America. It will mark a new era in the development of Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, those countries so rich in useful minerals and yet so remote from the world’s centres of culture and industry. Henceforth there will be no need of doubling the entire coast of South America to get to Lima or Valparaiso from New York. Until now, North Americans have preferred to go to South America by way of Europe, mostly via Paris and thence to the Suez Canal. Thus in order to get to Valparaiso from New York, many used to make a voyage around the world. Around South America, through the rocky and stormy Straits of Magellan so dangerous for navigation, steam ships are sent by only one great English company, the Pacific Steam Navigation Co. Its vessels run from Europe directly to Callao, the port of Peru’s capital, Lima.

It is manifest what a revolution in the economic destinies of South American countries will be brought about by the opening of the Panama Canal. First of all hundreds of sailing vessels, which have hitherto held sway over the entire Pacific coast of South America, will disappear, making room for giant European and North American steamers. At the same time the opening of the new route will tell favorably on the development of commerce between those countries and the United States. In the foreign commerce of those regions, as in other parts of the world, the principal role is played by Great Britain, about the imaginary decline of whose international commercial influence so much has been written of late. England still holds first place in the foreign commerce of Chile and Peru, as is evident from the following figures. In 1909, the exports of Great Britain to Peru amounted to £1,567,907, and of the United States to Peru, £846,127, while the imports of Great Britain from Peru were £2672,540, and the imports of the United States from Peru, £1,495,623. Similarly the exports of Great Britain to Chile, in 1910, amounted to 94,084,000 pesos (peso equals 36 cents), and of the United States to Chile, 36,629,000 pesos, while the imports of Great Britain from Chile were 127,087,000 pesos, and of the United States, 67,619,000 pesos. As to Ecuador, she receives annually imports from Great Britain to the value of 512,000 pounds sterling, and from the United States only 482,895 pounds sterling.

The Panama Canal will open up to the United States the markets of South America and make possible the realization of the cry, “America for the Americans.” New York will be 2,837 miles, New Orleans 3,550 miles nearer than London to the Pacific coast of South America. It must not be forgotten that, thanks to its natural resources, the Pacific coast of South America will develop from the economic point of view with extraordinary rapidity. John Barrett, director of the statistical bureau of American republics, has calculated that the foreign commerce of the South American coast, now amounting to $300,000,000, will soon reach the billion dollar mark. A whole series of facts shows that the capitalists of the United States are aiming at monopolizing this market and have been taking measures to drive their competitors out of these region.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1913/v1n08-feb-22-1913.pdf