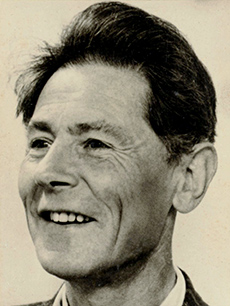

Gijsbert Jasper van Munster was a Dutch teacher and veteran Social Democrat who was active in Indonesia from 1910, including as a founding member of PKI, serving on its Central Committee, expelled from Indonesia in 1923, he was a senior figure of Dutch Communism, leading much of its anti-colonial work. In the anti-Nazi resistance, he was arrested in 1943 and died in Dachau shortly before liberation in 1945. The PKI was among the most vital and influential of the early Communist Parties in a colonial country. As the first Asian Communist Party to join the Comintern it was, in the first half of the 1920s, also the largest Comintern section in Asia. Working in, and partially leading, the popular Islamic party Sarekat Rakyat, the PKI played a central role in the mass rebellion that broke out against Dutch imperialism in 1926. In the aftermath of the insurrection, a mass wave of terror hit the Indonesian workers’ and anti-imperialist movement.

‘The Background and History of the Insurrection in Java’ by G.J. van Munster from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 6 No. 87. December 16, 1926.

On November 13th 1926 it was officially reported that “in consequence of a wide-spread conspiracy, the Communists in West Java and in several places in Central Java had risen in arms”. According to these official reports, the police in Batavia, the capital, were on their guard because they had been warned a few days previously. Later on 60 men in serried ranks advanced against a prison, whereupon a skirmish with the military guard developed, in the course of which about two hundred shots were exchanged and four communists were severely wounded.

After the attack had been repulsed, 30 of the attacking force occupied the telephone office. Shortly afterwards a division of the military took up a position in the Chartered Bank opposite the telephone office, whence they made a futile attack on the occupied office. The next move was that the telephone office was surrounded. The besieged made a sally; some of them succeeded in escaping whilst 17 were captured. The siege of the office was continued with reinforcements, until on the following day the rest of the garrison–three men in all–surrendered.

There was also fighting in other quarters of Batavia and conflicts took place in the rest of West Java, that is in the provinces of Batavia and Bantam and in the Regency of Preangar. In several places in the province of Bantam the population forced their way into the administrative offices, and in two places the native Governor of the district was killed. Whites were not killed, only a Eurasian, but many of the assailants were killed or wounded. In several places the police barracks and prisons were stormed, but in most cases the attempt to release the prisoners failed.

On November 15th, 500 insurgents armed with guns made an attack on Labuan which is situated on the Sunda Straits (which separate Java from Sumatra) in West Java. The attack was repulsed with loss of life, but the situation in the surroundings of Labuan and altogether in the province of Bantam was very alarming: the villages were empty, telephone wires were cut, barricades had been erected on the roads to the villages. Government troops were working with five wireless stations, the European ladies had fled to Batavia. In several places the insurgents were clothed in white which, with Mahommedans is a sign of their being ready to die.

In Central Java also attempts were made to start active warfare. The authorities seized secret circular letters and proceeded with arrests. Village schoolmasters were at the head of the movement. Attacks were repulsed leaving dead and wounded, and meetings were dispersed by force, wholesale arrests being made. On the other hand, informers were attacked, one of them being killed; attacks were made on prisons, but were repulsed. Here also telephone wires were out and the European personnel of the sugar factories was supplied with arms.

Within a few days the insurgents were obliged to surrender. In West Java, the insurrection did not include large masses, it is true, but it was fairly wide-spread and, as it broke out simultaneously in so many places, it did not give the government troops a chance of taking energetic proceedings at once; it was only in the surroundings of Labuan that it was possible to take immediate measures to suppress the revolt by force of arms. In Central Java, attempts at rebellion were only made a few days later and in any case, they were only of sporadic character. In East Java “order” was not interfered with at all.

Nevertheless there were wholesale arrests of communists throughout the country, including East Java.

In West Java the movement only calmed down slowly. Finally on December 2nd. i.e. 19 days after the outbreak of the insurrection, 350 men clad in white reported themselves to the central authorities in Batavia and offered to surrender. The Dutch Colonial Minister stated in an interview that the situation was at first uncertain. It was a few days before it became evident that the Government had command of the situation. The proposal of the European circles in Java to organise civic volunteers was rejected by the Government which feared that this would only increase the disturbances.

A semi-official report from Batavia states that it transpired from the investigations that the communist leaders in Java had resolved at the end of 1925 to provoke disturbances in 1926 as soon as the necessary money was at their disposal. In this connection there are said to have been differences of opinion with the leaders of the communist party of India, some of whom were out of their own country, for instance in Singapore. The plans for the disturbances in the night between the 12th and 13th of November are said to have been drawn up in secret meetings at various places on November 7th in connection with the anniversary celebrations of the foundation of the Soviet Power. The immediate orders had been given barely 24 hours previously, and, in addition to the measures taken by the Government, the failure of the insurrection was to be attributed to this and other defects of organisation.

The assertion that the communist party of India had been implicated was further maintained by the official authorities.

The Government has resolved to deport all the communist leaders in so far as they are not being pursued by the law for participation in the insurrection to an uninhabited district outside Java. Although the intention is only to strike at the nucleus by these measures, the number of those affected is considerable. Similar steps will also be taken against those participating in the reconstruction of the communist party. The questions of reinforcing the army and providing the police with better weapons are being considered.

The suspicion of some of the Dutch Press against the present Regent of Batavia, Achmed Djajadinigrat, the former Regent of Serang (capital of the province of Bantam) is rejected by the official circles. The suspicion had been particularly expressed in a remark of the Amsterdam “Handelsblaad” on an interview with Dr. D. Fock, the former Governor General; but in reply to some questions put by “De Tribune”; the organ of the C.P. of Holland, Fock declared that he was not responsible for these editorial assertions. Nevertheless a suspicion of this kind with regard to a “communist plot” remains characteristic of the situation.

In the Dutch Second Chamber, Dr. Albarda, the chief leader of the social democratic fraction, 24 strong, stated that the insurrection was “regrettable and reprehensible”, but he said no word about the background of the insurrection. In the so-called National Council of Java, in which there is a single social democratic member who represents nothing and nobody and was appointed by the Government he, a certain Stockvis, made a similar statement. It should also be remarked that a whole month before the outbreak of the insurrection, the police and the State administration of Batavia and its surroundings had taken the severest measures against the communist party.

Special emphasis should be laid on the fact that the above description of the course of the insurrection is based on official sources as, for the time being, none others are available.

What is the background of the insurrection in Java?

The reactionary rule of the Governor General, Dr. D. Fock, who retired at the beginning of September after five and a half years in office, protected exclusively the interests of foreign capital invested in Indonesia both from the social-economic and political point of view, and crushed under foot the interests of the native population. As regards social-economic conditions, the activities of the Government were characterised by far-reaching measures for “safeguarding the gulden” by reduction of wages, by limiting the apparatus of education and public health, which in any case are so scantily provided for in Indonesia, by increasing the taxation which has to be paid by the native population etc., whilst the profits of foreign capital were not only protected, but “safeguarded” at the same time as the gulden.

With regard to political conditions, the activities of the Government were adapted to the conditions which resulted from the measures taken in the social economic field. The predominance in the so-called National Council a mere parody of national representation was in the hands of the P.E.L. (Political Economic League), the political incorporation of the J.S.M.L. (Java Sugar Merchants’ League) and the Powers friendly disposed towards it, under the leadership of Dr. Talma, the former Government plenipotentiary in Indonesia, who had in the meantime been bought by sugar capital; his twin brother is Dr. Treub who, as the leader of the undertakings interested in the exploitation of the colonies, dictated his wishes, from Holland, to the “Viceroy” of Indonesia. This year it came to light that the P.E.L. had secretly held a conference with the present Government plenipotentiary, Dr. Schrieke, in order to start anti-communist activities. The costs were to be paid by the J.S.M.L., which insisted that the Government should induce the Regent, i.e. the most eminent of the former Javanese chiefs who has been degraded to a State official, to participate, which was actually attempted.

The popular movement was driven into illegality by a number of legal measures, the introduction of new regulations against “incitement to hatred”, against strikes and against the right of assembly and the right to form associations. These measures, however, only caused still greater dissensions between all the strata of native society and foreign capitalists, as is evidenced by numerous facts and verbal reports, even from bourgeois Dutchmen.

When he assumed office, the new Governor General, the Junker Dr. de Graeff, stated that he would make concessions to the native intellectuals, but that he would combat communism with all the means in his power. The social democrats who only have a few adherents among the white employees, praise this Junker to the skies as an “enlightened man”, but 3000 intellectuals, including representatives of organisations of the whole country, rejected the proposals of Dr. de Graeff at a nationalist council held in Soerabaia in September 1926.

In West Java, the situation was acute in August 1926, as the population of this district, in which the utmost poverty prevails, had refused to pay the taxes. West Java lacks the modern agriculture which is carried on in Central Java and East Java, and has nothing but rubber plantations; furthermore, a large part of West Java is in the hands of large landowners and, from the economic and social point of view, the conditions are absolutely mediaeval and are even pilloried by bourgeois newspapers of Holland.

In the last ten years the situation of the population of the whole of Java has grown much worse, whilst at the same time the admitted profits on foreign capital invested in Indonesia (with about 47 million inhabitants of whom about 35 millions are in Java) have not amounted to less than 35% per annum. An estimate for Java in 1924 shows an income of 39 Dutch gulden per head, i.e. of 195 gulden for a family of five persons or of 3,75 gulden a week for man, wife and three children.

The native population of Java consumes half of the imports quoted below, and has hardly any share in exports.

Imports increased from 300 million gulden in 1913 to 467 millions in 1924, exports in the same period increased from 317 to 910 million guldens. If however, with the aid of the wholesale index figures, we calculate exports and imports at their actual value (i.e. excluding the varying purchasing power of money), we find, reckoning the imports in 1913 at 100, that imports have decreased to 79 whilst exports have risen from 106 to 215.

The causes of the outbreak of the insurrection are not only to be sought in the increased exploitation of the population of Indonesia but also in the general awakening of the suppressed peoples in the Far East. The insurrection in Java is connected with the recent victories of revolution in China. It is therefore to be expected that, in spite of the suppression of the present insurrection, the consolidation of the victory will be a new stimulus to the revolutionary movement in Indonesia.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. A major contributor to the Communist press in the U.S., Inprecorr is an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1926/v06n87-dec-16-1926-Inprecor.pdf