Briggs gives us a tour of the October 10, 1932 hearing of the Scottsboro Case before the robed ghouls of the United States Supreme Court.

‘Whose Supreme Court?’ by Cyril V. Briggs from Labor Defender. Vol. 8 No. 11. November, 1932.

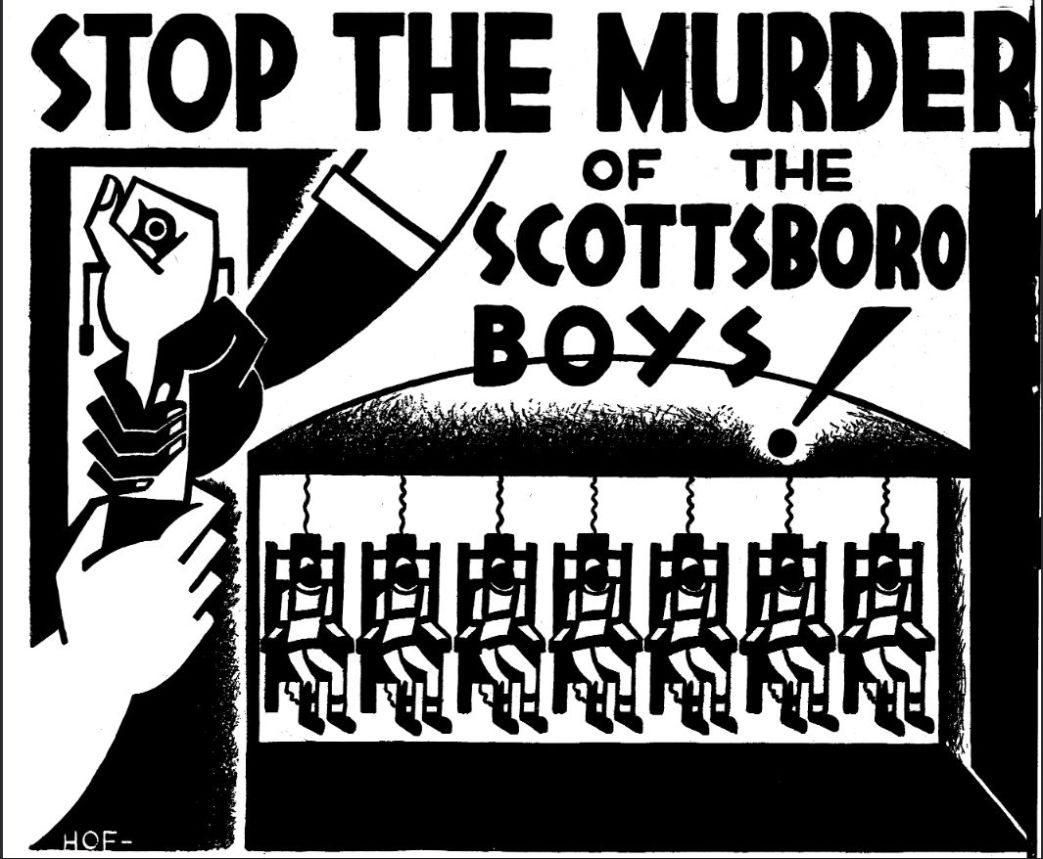

Nine old men, sitting in the highest court of American capitalism, faced on October 10 the necessity of deciding whether it would be safe to uphold the hideous Scottsboro legal lynch verdicts in the face of the angry thunder of protest from workers and intellectuals throughout the world, and the rising resistance of the Negro masses to the capitalist lynch terror. The court has not yet announced its decision.

The historic class forces which have clashed in countless battles around the Scottsboro Case during the past 18 months were well represented at the October 10 hearing before the United States Supreme Court. These forces filed into the court in two opposing streams. From their conspiratorial chambers came the nine old men of the Supreme Court, togged out in sartorial devices aimed at enhancing their dignity. From entrances set aside for the privileged had previously come other representatives of the capitalist class, including a large delegation of Alabama Congressmen and other members of the minority of white landlords and landowners exercising a bloody rule over the “Black Belt.” Congress was not in session, and most of its members were touring their districts peddling their pre-election lies and sham promises, but the Alabama contingent in Congress was on hand to demonstrate its solidarity with the Alabama lynch courts which had rushed nine innocent Negro children through a farcical trial to death sentences for eight and–for effect–a mistrial for the ninth.

These representatives of the Alabama ruling class seated themselves around Thomas E. Knight, Jr., Alabama Attorney General who was present to oppose the appeal argued by the International Labor Defense attorneys and to defend the lynch verdicts.

The International Labor Defense attorneys, supported by the world-wide mass protests, had later forced the Alabama Supreme Court to admit the existence of irregularities in the trial of Eugene Williams, one of the eight originally condemned to death, and had ordered a new trial for this boy. The majority opinion upheld the lynch verdicts for the other seven. In a dissenting opinion, the Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court was forced to admit that none of the boys had received a fair trial.

Knight’s father, a member of the Alabama Supreme Court, had previously concurred in the majority opinion of that court upholding the lynch verdicts. Seated with the Alabama group was also former United States Senator Thomas J. Heflin, notorious Negro-baiter.

Opposing these forces of capitalist reaction were hundreds of Washington Negro and white workers who had filed into the court room past the hostile challenges of a heavy police guard specially called out for the occasion. The newspapers reported that the entire Washington police force had been mobilized in fear of hostile demonstrations by workers against the lynch verdicts and the United States Supreme Court. These workers were there to show their solidarity with the Scottsboro victims of capitalist justice, their resentment against the murderous frame-up of those working-class children, and finally their support of the arguments of the battery of famous attorneys engaged by the International Labor Defense for the oral argument before the court.

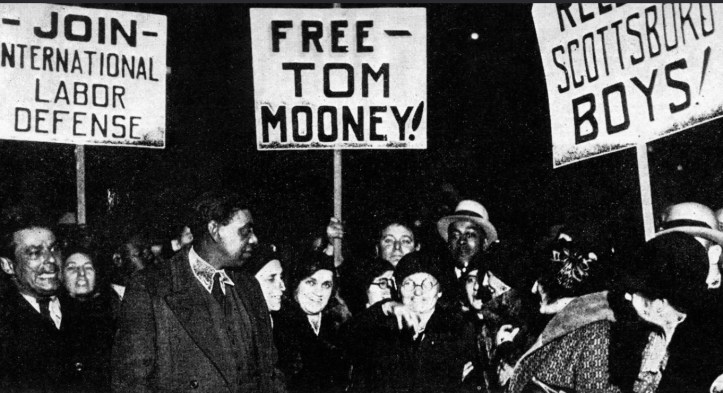

This solidarity of the white workers of the whole world with the persecuted Negro masses was dramatically demonstrated in the court room itself, with the entrance of Mother Mooney, mother of Tom Mooney, victim of another notorious frame-up by the American ruling class. A flunky of capitalism in the person of the U.S. Marshall attempted to bar Mrs. Mooney from the hearing on the grounds that she could have no interest in the Scottsboro Case and the fate of the nine Negro lads. Mother Mooney who, in the company of Richard B. Moore, Negro proletarian orator, had travelled thousands of miles throughout the United States, in defiance of the orders of her physician, for the Scottsboro-Mooney defense campaign, brushed aside the arguments of the U.S. Marshall. She was permitted to remain.

The high court of capitalism was definitely on the defensive. It had felt the impact of the thunderous mass protests welling up from all corners of the world. It sensed the breaking down of the capitalist-erected barriers between

the white and Negro masses. The cry of millions of workers against the lynch-justice was ringing in its ears. It realized that Scottsboro had become the symbol of working-class unity against the bloody rule of the dying capitalist system, against the savage persecution of the Negro nation in the “Black Belt.”

In the three cases preceding the Scottsboro argument, the justices took an active part in questioning the attorneys on both sides. In the Scottsboro Case they maintained a studied silence. This silence was in sharp contrast to their animated interest in two liquor cases, in which they were greatly concerned on questions such as for what number of days a search warrant in a liquor case was good, and whether it was necessary to have an affidavit in order to renew it. Quite clearly, the justices were afraid to ask questions in the Scottsboro Case, both for fear of dramatizing the fundamental issues of Negro rights involved, and for fear of revealing their hatred and hostility toward the Negro masses and the entire working-class. Their antagonism toward the Negro masses was clearly exposed, however, in one of the liquor cases in which one of the attorneys was a Negro. Both Justices McReynolds and Sutherland openly showed their resentment at the appearance of a Negro lawyer before the court, bullying and baiting him throughout the hearing. In the Scottsboro hearing, however, all the enthusiasm of the justices for the liquor cases had vanished.

Walter Pollak, who argued the case for the I.L.D., forcefully exposed the facts of the frame-up of the nine boys, masterfully presenting the evidence proving that the boys were not granted a trial, “were denied due process of law,” were given no time to prepare their defense, were not permitted to communicate with their parents, although all of the boys were minors; that the very defense lawyers foisted by the Scottsboro court on the boys had failed to call a single defense witness, had never opened or closed to the juries, had not consulted with the parents of the boys and made no proper preliminary motions, that the boys were tried, convicted and sentenced to death in less than two weeks.

He declared that the boys would have had proper attorneys had they been granted time to prepare their defense, and in proof, he pointed to the fact that they were later ably represented by General George W. Chamlee (a Southern attorney engaged by the International Labor Defense, who laid the basis for the appeal to the Supreme Court).

Justice McReynolds, who had listened with an air of boredom to the argument of the I.L.D. attorney, immediately pricked up his ears and leaned forward when the Alabama Attorney General Knight opened his defense of the lynch sentences. So did Heflin and the delegation of Alabama congressmen present. Knight argued that the Alabama Supreme Court had reviewed the sentences and had declared them to be just and made the significant statement that the Alabama justices know their local problems. He had no apology for the severity of the sentences, he declared, with an approving nod from Supreme Justice McReynolds. Launching into a demagogic defense of Alabama lynch justice, he declared that Alabama regards with great jealousy the rights of a defendant, adding “regardless of race or color.” He denied that the trials were conducted in an atmosphere of lynch terror, passing over the demonstrations of the mob hailing the first lynch verdicts, and offering as proof of his argument that the mob failed to lynch the jury which reached a disagreement in the case of the ninth boy, Roy Wright.

No illusions! The Supreme Court belongs to the ruling class as completely as the courts in Alabama. Only class justice can be expected from this sancta sanctorum of Wall Street government! Only mass pressure–mass protests on a swiftly increasing scale–will free the Scottsboro boys will save them from the electric chair! The Scottsboro boys must not burn! We demand their unconditional freedom!

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1932/v08n11-nov-1932-LD.pdf