One thing is a constant: Communists go to meetings. In this chapter Goldschmidt attends a gathering of English-speaking revolutionaries, describes buildings covered in poster art, tells of the power of the names Lenin and Liebknecht, and watches 54,000 tons of flour enter the hungry city.

‘Moscow in 1920. Chapter IV’ by Dr. Alfons Goldschmidt from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 3 No. 17. October 23, 1920.

The English Speak

AGAIN the Great Opera House. Something was being done with the English, they were being fawned on, pawed over, petted and tickled with inscriptions, warnings, challenging placards. “We are for children, for future, for humanity ” Or: “We started the social revolution, we started it alone, let us go together to the end.” Or, they were welcomed in view of the new color of Russia: “Welcome, comrades, to Red Russia.”

They were being played up to, they were being belabored with their own principles, to convince them. They were not loved and yet they were flooded with kindness. All this was to spur them it was unnecessary in my estimation. For one, English trade union leaders look upon things with clear eyes, they have an appraising eye, that sees a thing as it is. They do not look for the goal far away, they are no problem hunters, no emotionalists, but they see things as they are. They see the present rather than the future, even when they seem very revolutionary.

Several of them spoke in the Great Opera House, surrounded by many Soviet leaders (Lenin was not present). They spoke very violently, very revolutionary. They spoke and sweated, they shook their fists, they set one firm foot forward, they spoke themselves hoarse, and they were cheered wildly. No one understood them, but they spoke from conviction, urged by the flame of the moment, before this public hungry for help, this people abandoned by the world, that desires peace with such consuming fervor. England is lord over war and peace, and the English labor leaders in England are no inconsiderable factors. They do not approve of a great many things in Soviet Russia, but they want to help the country, and this government. They do not desire that system for England, but they approve of it for Russia. They would have approved it even without the challenging posters, without petting and lashing. For they are shrewd, but not cold-blooded. This visit was really a victory for Russia.

So they spoke: red overhead, red at their feet, and before them a people yearning for help. Here and there a word of censure, a cutting remark, some bitter comment. But the workers listened quietly and cheered. The last to speak was Mrs. Snowden, a lady correctly booted, delicate but not lovely, confident but not cold. Not a woman storming for a goal, not a woman with a red flag, but a rosy-tinted woman, powerful of word, but pale of color. She said what she meant. She declined: “Go your way, we go our way to Socialism.” After every speech the content was translated for the hearers. At first Balabanova translated. Clearly, fluently, without hesitation, almost word for word. A fabulously gifted linguist. All well-educated Russians speak several languages, but Balabanova, one might say, has a number of mother tongues. Now they understood, and they applauded again It was not Communism that was now being translated, that the English speakers had spoken, but it was gratefully applauded.

Russians spoke. Tomsky, the Chairman of the Trade Union Federation, spoke. He spoke fast, with vigor, familiar with the public. Other Russians spoke, and always there were cheers. And now came Abramovich, the Menshevist leader. He spoke to an audience that was unfriendly to him, and was greeted by small scattered groups of followers only. He was pale m he spoke. He was often interrupted by violent calls of opposition. He spoke smoothly, courageously. He made the most of the presence of the English. They tried to force him to end his speech, but the chairman of the meeting called the meeting to order with: “Behave like Communists.” He finished his speech. It was a long address. They called him Kolchak, but he continued to speak. I do not know what he said, I only know that it came from the soul, that there was fervor in him, too. He spoke in a rage, he unburdened himself. The Mensheviks today are united with the Communists on the great questions, especially on the question of war with Poland. But they are an opposition party, and they are by no means a weak party. When he ended, the applause was again only group applause from his followers. Otherwise there was hostile coldness. It was plain this man was respected, not loved.

But then came that wonderful thing again. Even during the meeting the public had been singing the Internationale. Now it sang the song of the Red Flag. It was steeped in this song, there was military rhythm in the song, while they were descending the stairway. There was massiveness, determination, power, in this song of the masses. It begins with a ringing clearness, and gains force and momentum as it proceeds. Slowly the crowds rolled out through the exits, in step to the tune, held in check by the song, pushed along by it, down the stairways and through the doors, and out upon the wide sunny square in front of the Great Opera House.

A Proletarian Meeting

At the end of the Red Street, the proletarian main thoroughfare of Moscow, is the Zoological Garden. There are only a few animals left. The cages at the entrance, a long row of cages, are empty. But otherwise nothing has been destroyed. Water birds are perched on the rocks in the lake of the park, and the meeting halls are ready for the meetings. We are in a large hall, an auditorium with light effects like those in a gigantic tent. The light streams in through the door with such force that the ceiling seems transparent. In front beside the stage are a few boxes, constructed of wood. On the stage is a small table for the chairman of the meeting. In front of the center of this table is the chairman of the Communist Party of the district. He is a small, black-haired, long bearded workman, smartly put together, whom we already knew. He has been abroad and is a linguist. He speaks fast, one might say with graceful violence, with his hands behind his back, applauding his own particularly apt points. That seems to be a Russian custom among speakers. This hand clapping does not denote self-applause, but is meant to emphasize important points, and to denote reverence for things mentioned as worthy of such reverence. The public applauds also. Or the public first applauds the striking passages, and then the speaker joins in the applause.

Next to him a man with a blond mane, a tender, bony face, a mild leader’s face. He is half-woman, half-hero. He is the head leader of the Red Ukrainian army. He speaks later, thunderingly, lifting the public up with his hands, filling the hall with his voice, giving the effect of a cyclone. He speaks of the Paris Commune, he hurls giant blocks into the audience, he throws his fists at the people, he is transported. A fervent flame burns in his eyes, he is fire and sword. We spoke also, brought greetings, and promises. I speak plainly to 5,000 people, and all understand me, even in the most obscure corner. But this man swept and raged through the audience, he hammered against their heads, he shook them, he tore at them as at young trees. A powerful speaker, a man to speak to troops, to armies. There was a sigh of relief when he ended, for the pressure was becoming unbearable.

Meetings are tape worms in Moscow. However, the public is patient, it cheers again and again, it listens, sits up and holds out. It is attentive, does not flutter and whisper in corners during a speech. Silent and enthusiastic, absorbed and explosive. I have never had such a proletarian audience before me. The German audiences are more visibly disturbed, more spoiled, need to be brought oftener to the platform. Possibly they are more critical, more experienced. But the speaker makes a greater effort, is at a higher tension, for he must arrest their attention every moment if the audience is not to slip from his grasp.

Everywhere in Moscow there is a wave of applause at the mention of Spartacus. It is the firm name of the German revolution, so to speak. The chairman spoke the word, spoke the name of Liebknecht, and the cheering doubled in volume. I shall speak later of the effect of this name. It is immense.

A resolution was accepted and passed, and applauded. We were then asked to enter one of the boxes, for the performance was to begin after a short pause.

This was no Grand Opera, this was a proletarian performance. It was not yet new art, proletarian art, but it was proletarian in spirit.

For this audience was purely a proletarian audience, and the acting, the singing, the speaking was accepted with a childlike readiness and simplicity that touched the heart.

First there were several pertinent scenes, with folk-songs historically arranged. For instance, there was a Volga boat song, a melancholy towing song, a drifting song, a song of the deep, wide river, a Gorki song. The last was a scene from the days of the shooting down of the proletarian masses demonstrating before the Winter Palace in Petrograd in 1905. A wounded man stumbled in, and a proud, angry, passionate song was sung over this blood.

Thereafter song upon song was sung by artists, men and women, whose names were whispered with approval. Heavy melodies, playful village songs, rhythmic stamping songs, jubilant songs, also the Internationale. They sang again and again, they repeated the songs when the audience called “bis, bis”. Next to me sat a curly-haired, apple-cheeked, round-headed proletarian girl, of about fifteen. She raged, she perspired from exuberance, she was quite beside herself. She pounded upon my ear drums with her “bis, bis”. I was completely overwhelmed.

But there was something in the center aisle which drew me and would not let me go. It was a girl, youthfully delicate, covered with a red veil. The small peasant face with a small, almost snub nose was visible, and her black hair gleamed through the veil. Her head rested on the shoulder of a young giant, a blond, short-haired, Russian Cheruscan. His arm was about her waist, and he adored her from under his blond lashes. He held her tightly, for she wept with almost every song. She was stirred to her very soul, moved beyond words, and was weeping her heart out against his strong breast. It was a proletarian tribute, a memorial of the primitive soul, that I beheld there. Again and again my eyes were drawn to this group, which stood so alone in the surrounding throng.

Children were sitting upon the orchestra parapet. No one disturbed them, they were not fetched down with authoritatively threatening fingers. They bent toward the stage in childish awe. They laughed, twittered and murmured sadly, when the song was melancholy, when a song lamented the death of a proletarian hero.

At the last a boy, a proletarian boy, came upon the stage. Possibly twelve years old. He recited a proletarian song in ringing tones. The audience knew him. It was plain he was already used to reciting poems at meetings, was used to speaking at meetings. He was wide awake, put the right leg forward with energy, and proceeded without a tremor. But he stuck fast in the midst of it, he couldn’t make it go, he pulled on it, he improvised a little, but it would not go. The audience laughed, applauded, consoled him. Women petted him. to make him happy again. No one heckled him. He had simply broken down in his speech, that was all. He had done his best.

Finally the closing speech, applause, curtain—going home.

In going out some one said behind me: That must be a German comrade; his pipe never leaves his mouth.

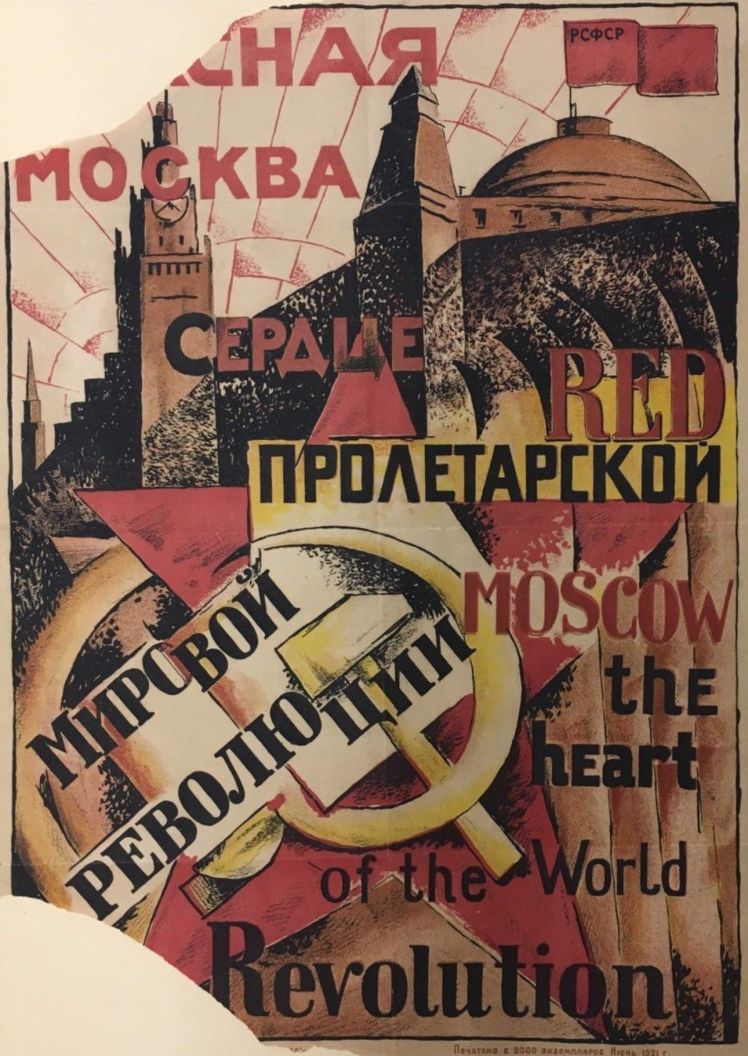

Posters

You will find posters on every wall, in a thousand stores of Moscow, on telephone poles, in rooms, in factories; they are everywhere. Picture posters for propaganda purposes. Perhaps a proletarian rock, flaunting a red flag, with a capitalist ship going to pieces at the foot of it. Or a poster recruiting for the Communist Saturdays, with a description of the consequences of laziness, and beside it the results of industrious work. Or else a picture poster attacking the old greasy Czarist officials, the pot-bellied popes and the aggressive military officers. Placards with red stars, recruiting posters of the Communist Party, showing a procession of workers passing by some representatives of the old order with an air of refusal, and entering a house upon whose gable are the initials of the party.

But these are not the most interesting posters. More remarkable, more significant are posters of a different order. For instance some wall bears the information that somewhere proletarian courses are being given on world problems, literature, problems of natural science, with excursions into the field of bacteriology, geology, agriculture, accounting, finance, etc. Entirely gratis, of course.

Another poster requests people with a love for inventing and inventors’ talent to invent all sorts of substitutes. For there is a great scarcity of raw materials in Russia. For instance a substitute for soap. For such a substitute a premium of 25,000 to 30,000 rubles is offered. The invention is tried out. It is distributed and the public is asked to report on its usefulness. I read of such a distribution of trial soap in a Moscow paper while I was in Yamburg. This practice is to be well recommended. During the war the German people were flooded with every conceivable trash as substitutes. Powdered chocolate of clay, powdered eggs of chalk, cake and pudding of bone glue, and such like whitewashed horrors. Had the people been asked first, the manufacture of substitutes would probably have been less variegated, but cleaner and a great deal more honest.

It goes without saying that study in the conservatories is gratis also, just as there is no charge or expense to any school or university training. Of course, there are still private teachers, especially for languages, but there are no more school fees or expenses necessary for a course of study. There is a poster of a state conservatory which recommends its course of history of music, a course of folk music, physiology of breathing, a course in instrumental technique, etc. Nor are the conservatories over-crowded. The system of free instruction seems already to be sifting the wheat from the chaff. Formerly every blockhead struck with the finger or vocal madness indulged his weakness as long as father’s money bag held out. The so-called monopoly of education was a monopoly for blockheads. A removal of the education monopoly will result in setting real talent free. The music fraud, the sickening pedagogic fraud, the advertisement regime, the hunt for pupils is at an end.

Another poster calls the proletariat of a certain district to an evening discussion of questions on art. One comes to these discussions, and discusses valiantly, clashes with the others, brandishes sophistries, is clover or dull, as the case may be.

At least such things scratch the surface, oil up one’s thinking apparatus, and make for mental agility. The so-called musicales with their lemonade souls, their long-haired atrocities and their badly brewed tea are sufficiently tiresome. They are mostly match-making institutions, nothing more.

Another poster announces an industrial exhibition, with a platform where the principles of a technical education may be discussed.

The Department of Economics of the City of Moscow is setting aside one evening a week for discussion of the problem: “What is the best method of growing vegetables?”

One poster asks the public to attend several lectures “given by technical experts, dealing with the technique of the use of clay as a building material. They will show that as far back as antiquity clay was used in construction; they will discuss the economic advantage of brick construction, and they will make every effort to interest their hearers in the use of bricks as building material. They are not interested in winning over, say a group of profiteers, or a syndicate, or possibly a sleepy Minister of National Economy, who is not even able to telephone without aid, but they want to interest the people. Here again I am tempted to become nasty. I feel the gorge rising within me at the memory of such impotence on the part of German Ministers. The projects for German workingmen’s homes were submitted to them on a silver platter, so to speak. But some highly paid blockhead could not be aroused from his lethargy. He could not even telephone. He referred the project to the regular routine for such matters, disclaimed his competence to deal with it, and continued his slumbers. The next day he published a speech both disarming and agitating, that for sheer stupidity, meaningless piffle, and school boy logic could not well be equaled. I feel the gorge rising, I feel myself getting hot under the collar, when I think of that idiot.

Another poster announces lectures on forestry.

Further along there is an appeal of the Social-Revolutionists against the Poles, and not far from it another invitation to take part in discussions about religion or about some technical problems.

The Soviet Republic makes a determined propaganda in favor of sports. In every corner, on every wall, and other spaces lending themselves to the purpose, there are sporting posters. Whoever has the desire may become a sportsman. Private yachts, tennis court rentals, and expensive yacht club memberships are not required.

Only the men at the top of their profession have charge of instruction in technical courses and lectures. There are no entrance fees of any kind. Also the people are being familiarized with all the facts and possibilities of science. The discussions on art, philosophy, religion, and politics serve to liberate the people from heaviness, self-consciousness, and timidity. One becomes acquainted with one’s own resources, it is good training. This also is only a beginning, but at least it is a beginning.

I do not believe that one with half an eye for soundness can find fault with this activity. Nations are hungry for inspiration, for knowledge. Whoever knows proletarians, whoever has been able to understand them, knows how great this hunger is.

It may be noticed in the morning at the news stands. The workers stand in line, they form long queues as in Berlin in front of the cigar stores. Every worker in Moscow reads several papers. In Moscow the posters are read, the passages pasted on at the Rosta, the official telegraph station, are read. The various writers of articles are known, their style, the incisiveness of their various pens is known.

Whenever any one group has a grievance, the wound is plastered with placards. Whoever wants something or other, speaks from a wall and later from the platform. There are thousands of opportunities in Moscow to go before the people, so long as one has something to say.

All nations are thirsting for enlightenment. I believe that the time of beginning enlightenment is here. Even other countries use more and different placards, not alone Russia. Placards express the soul of a people, the tendency of the times, they speak the will of a people. They reveal whether a people is heading upward or downward. There is a marked difference between the posters of Berlin with their skirt dance allurements and the posters of Moscow. I do not mean to speak politically. I merely mention what I saw, no more, no less. I repeat this assertion, else I might be condemned for a miserable fanatic.

Lenin and Liebknecht

Not an office in Moscow, not a Soviet house entrance is without a picture of Lenin, without a picture of that half-smiling head and the slight turn of the body at the desk; with the soft collar (there are no stiff starched collars in Moscow, for there is no starch). This picture is everywhere. One sees it in all sizes. Lenin everywhere. There are also pictures of Radek, Zinoviev, Bukharin, Balabanova. There are group pictures of the principal figures in the Third Internationale, arranged in such a way that Lenin appears at the top. There are many pictures of Marx in many rooms, in many store windows, in many offices, especially a Marx portrait which in my estimation is not a good likeness. But more often than the head of Marx, much more often, one sees the head of Lenin.

The history of Lenin, Lenin’s development, is well known. His personality has often been described. Perhaps it is not commonly known that he, too, for a time stood alone, and was even ridiculed by his comrades. They called him a brakeman. Radek and Bukharin did not agree with him. But Lenin was right—he was right for Russia. That cannot be questioned. He was right—for Russia.

Today every one loves him, even his political enemies. Not one opponent speaks of this man with disrespect. Not a Menshevist, not a Social-Revolutionary, not a Kerensky man, not a monarchist. They all respect him. In one bourgeois family, of which I will speak later, he was being praised for his idealism and his sense of justice.

Lenin wields a colossal influence over the Russians, over entire Russia. He is like a warm gulf stream. He is feared because he is loved. He is the court of last appeal. Every one knows he works hard from morning till night. His work is divided, well organized. His work calls him, stimulates him. He is a living example. His name is used as a threat and as a spur to greater effort. Wherever he shows himself he is cheered. People who have spoken with him several times admire Lenin the fiery diplomat, the sure-footed on the brink of the abyss, the Jupiter, the smiling Lenin, the punishing Lenin. He is one of the best publicists of Russia. His pamphlets are examples of a literary virtuoso, of a prospector for words and ideas, of a systematic thinker. They are clear, concise, free from bombast, and real. One does not have to agree with his conclusions in order to admire their logic. They are unobtrusive, like himself, the man who has so much power by reason of the confidence placed in him by the proletariat, and who lives so simply. He never dines, he eats, he satisfies his hunger. He draws no larger salary than the salary of a Moscow workman, 6,500 rubles per month. He lives in the Kremlin. But he does not live there like a prince, rather he lives there to escape the crowds, to escape the love, the complaints, the appeals. He lives in the Kremlin as a symbol. He is no longer the revolutionary leader so much as he is the expression of the will of the people, the longing of the people, their development. He does not lead with a sword, he is not a dictator from above, he is being carried and holds the reins, while the people voluntarily carry him upon their backs.

One day as I was working with one of the managers of industrial combines (Centrals), a letter came from Lenin’s office.

He turned an ashen grey, hastily tore open the envelope, and then breathed a sigh of relief and smiled. “Why did you turn pale?” I asked. He said, “It is a letter from Lenin.” A letter from Lenin is no ordinary letter, not the letter of some people’s delegate. It is a letter from Lenin. It is like a toga, it holds happiness and pain. The man has an unheard-of power for good, the power to elevate, the power to inspire, as no Russian Czar has ever had. Lenin is Russia today. With him or against him, Lenin is Russia today. That is true, it is a fact, people are saying it on the streets in Moscow.

Karl Liebknecht has become a saint in Russia. I have seen hundreds of pictures of him in Moscow. I saw pictures of Liebknecht in his prime, pictures of the assassinated Liebknecht, pictures of Liebknecht on the stage of theaters, pictures of Liebknecht lying in his shroud, strewn with red tulips and lilies of the valley.

Proletarian clubs are named after Liebknecht, streets and regiments are named after him. At every mention of the German proletariat and the German Revolution, Liebknecht is mentioned also.

But he is not only identical with the German Revolution, his influence extends far beyond the German boundary. Liebknecht today is the hero of freedom in all the proletarian schools of Russia. Poets have sung of him, he is being imitated, he is loved as one loves a beneficent natural element. One might say that he is the Siegfried of the proletariat in Moscow.

Liebknecht would never had reached such power had he not been murdered. His influence is only just beginning to be felt. He will attain fabulous power, a name which will resound far beyond Germany.

The pictures of Liebknecht which appear in Moscow are often pale likenesses. I have seen very few striking pictures of him there.

You have the feeling in Moscow: Liebknecht will become a legend. He will become an epic, a passion way, a Golgotha of the proletariat.

Liebknecht’s death was a sacrificial death. Moscow feels that.

Transportation of Flour

Eighteen heavy drays are passing the wall of Kitai. Eighteen transport wagons loaded with flour. Fifteen sacks of flour to every ton. That makes eighteen times 3,000 pounds, or 54,000 pounds of flour.

The drivers are dozing upon their seats. Not a soldier accompanies the transport. The horses walk slowly. It is a hot day. A gallop or a trot in this weather would be uncomfortable.

54,000 pounds of white flour, wheat flour, not potato flour. 54,000 pounds of flour are slowly being transported through Moscow.

There is no quality bread in Moscow, at least not quality bread rations. There is bran bread, heavy with a reddish tinge. One longs for white bread, fresh white bread, flaky white bread with light yellow butter.

There are hungry people in Moscow to whom white flour would almost mean an escape from death.

But not a soul pays the least attention to the flour load. No one disturbs it, no one stares at it. The wagons pass by undisturbed along the Kitai wall, across the wide square near the Kremlin. Nobody thinks of taking the wagons by storm, of stealing from the load, of cutting open a flour sack while the driver is asleep.

And the eighteen wagons pass through the city, across the square.

Stealing has not yet been abolished in Moscow, robberies are still being committed in Moscow. Stealing does not disappear so rapidly, nor are souls changed overnight.

But the transports of flour, eighteen wagons each with its load of 3,000 pounds, 54,000 pounds altogether, a joy for the hungry, a life-giving load, a life-saving load, pass on their way through Moscow, unmolested.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v3n17-oct-23-1920-soviet-russia.pdf