The U.S. has a fantastically rich working class history. As part of the wave of strikes begun with New York’s 1909 ‘Uprising of the 20,000′, Cleveland saw a bitter garment workers strike in 1911 that received the aid of that city’s large Socialist Party, which grew itself during the conflict. This period gave rise to both the Amalgamated Clothing Workers and International Ladies Garment Workers’ Unions; two of the most important unions in U.S. history. Pauline Newman, sent by the I.L.G.W.U. to Cleveland as a lead organizer after the walk out of 6000 textile workers, mostly women and many immigrant, is deeply impressed by the collective and individual personality of the strikers, some of which are introduced by her, including by photograph.

‘Some Phases of the Cloak-Makers’ Strike of Cleveland’ by Pauline Newman from Life and Labor (W.T.U.L.). Vol. 1 No. 10. October, 1911.

On the 7th of June, 1911, nearly 6,000 cloak-makers, comprising cutters, pressers, skirt-makers, and finishers, men and women, some even children, went on strike, after having been refused the following demands:

General Demands

1. The working hours shall be fifty (50) hours per week, and shall be as follows: From 7:30 a.m. to 11:30 a.m.; from 12:30 to 5:30 p.m.; Saturdays, from 7:30 to 12:30 p.m. 2. No Saturday afternoon and no Sunday work.

3. Overtime work shall be not more than two (2) hours per day, during five (5) days in the week.

4. Week-workers shall be paid double time for overtime.

5. All legal holidays shall be observed.

6. There shall be no charge for machines, power or appliances, nor shall there be any charge for silk and cotton.

7. No inside contracting or sub-contracting.

8. No operator or tailor shall be allowed to have more than one helper.

9. There shall be no time contracts with individual shop employes, except foremen, designers and pattern graders.

10. Price list shall be exhibited in a prominent place in the factory, where work is distributed.

11. Prices shall be adjusted by a joint price committee to be elected by the employes in the shop, the outside contractors and a representative of the firm.

The various branches of the trade made separate demands for wage scales and other details.

Employers Surprised

Evidently they, the employes, surprised their “good” employers by making any demands whatsoever, for had not they (the employers) been giving money away? They gave money to charitable institutions, to religious institutions–they even gave money for educational purposes. In short, they gave money to everybody; were generous in everything except in wages of their employes. They are very indignant over the audacity of their employes in presenting the above demands. Perhaps they are right in being indignant–who knows? For just think of the nerve their employes had! To demand the right to be organized! To refuse to accept charity! And demand justice! To demand that which is coming to them–an increase in wages, so as to be sure of a comfortable living! I tell you, friends, the workers are beginning to get nerve! About time!

And so the fight is still on. It is a bitter struggle. Both sides are determined to win the fight. And while the employers are of one nationality only, and have on their side the police department, the court, guards, thugs, money and power, they are, in the end, bound to lose. Despite the fact that the strikers have about seven nationalities amidst their ranks and the deaf and dumb to take care of, the police department against them, guards judges to fine them the strikers are to annoy them, thugs to assault them, bound to win; are bound to come out the victors! For the strikers possess one power–that of making cloaks! Guards can annoy the pickets, but they cannot make cloaks; the police can arrest the girls, but they cannot finish skirts: a judge can render a decision in favor of the manufacturers that cuts the law into pieces, but he, too, cannot cut garments, and garment cutters are what the employers need. The above mentioned allies are an additional expense to them. That is all.

The manufacturers have no workers, none to add to their treasury. They are losing orders, losing trade, losing the season, losing their philanthropic reputation, but will not give in. Mammon’s pride!

The strikers, on the other hand, are as enthusiastic, as determined, as they were the first week of the strike–determined to stay out ten more weeks if necessary; until their demands are granted. They believe in their united effort, they believe in their Cause. They are believers in themselves, and as such are bound to win.

The strikers are like the man of the Jewish legend, who, while walking on Swampy ground, moved steadily on as long as he believed in himself; only when he ceased to believe in himself did he begin to sink. The strikers believe in themselves; therefore their ground is solid as rock.

Not One Deserter

Ten weeks on strike, and not a single striker has deserted the ranks! They have resisted all kinds of temptations that came from the employers and their servants, who have tempted them with higher wages, shorter hours–with anything and everything, if they would only leave the Union. But the workers knew that this would only be temporary. And they turned away with disgust. They have learned a lesson that of the right to organize, and of the value of organization. They are ready to live for it, ready to fight for it–nay, ready to die for it! The strikers know that they are fighting for a great principle that of Labor’s right to live, to enjoy, to aspire, to be free! For this they are at all times ready to face starvation, if need be, to remain without homes, to see their children suffer the pangs of hunger, to be insulted and dragged into jail, to be shot like dogs; in short, to risk their very lives–their own and those dependent upon them! Nothing can buy them, no one can bribe them; willing to sacrifice everything in order to stand by their Union.

Yet the employers, not long ago, issued a statement that they, too, are fighting for a principle. Of course, they are! the principle of the almighty dollar. “Principle!” What an insult to the word!

Manufacturers Refuse Arbitration

About two weeks after the strike was called, the State Board of Arbitration came to this city and asked the leaders of the strike whether they would be willing to arbitrate. The reply was “Yes,” while the reply of the manufacturers was “No.” Three weeks later the Board of Arbitration tried again to convince the manufacturers of the fairness of arbitrating at the present time, but the manufacturers gave them the same answer, “nothing to arbitrate.” At the same time, however, they issued statements–such as “We have always treated our employees reasonably,” “They had fair conditions,” etc., etc. Talk about nerve! Well, the strikers knew that the public at large had begun to ask, “Why, then, are they afraid of a committee of arbitration?” Because of such remarks, we felt that a public meeting would be in place. Let the public hear both sides and judge.

Mr. John A. Dyche, General Secretary-Treasurer of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, wrote to Mrs. Raymond Robins, President of the Women’s Trade Union League, asking her whether she could arrange such a meeting. We all felt that the meeting ought not to be called under the auspices of the Union, because we wanted to get the public at large, and for fear that some might not come if it were held under the auspices of the Union, we thought that the Women’s Trade Union League was the proper organization to call the meeting.

Mrs. Robins was bound for Westmoreland (always on the job) and could only stop for a day or two. She arrived on the day when strikers, their wives and their children, were parading through the streets of Cleveland, demonstrating their strength, courage, determination to win their just fight.

Mrs. Robins was met by a group of girl strikers and by the writer. When informed of the parade she refused to go to the hotel and rest, after her long and tiresome journey, but went right into ranks of the strikers and paraded for nearly two hours.

Public Meeting

In one day, practically, Mrs. Robins succeeded in interesting at least three women in the situation of the strike. Women who had been sympathetic and felt the justice of the demands of the strikers, but who, for some reason or other, had abstained from taking any part in the strike. Mrs. Robins then, with these three women, arranged a meeting for July 24. Unfortunately, Mrs. Robins could not stay for the meeting, but, fortunately, Frances Squire Potter came to take her place. Invitations were sent out to the Manufacturers’ Association, to the Chamber of Commerce, to the Federation of Labor, and to the strikers’ representatives. The manufacturers and the Chamber of Commerce answered by mail that they would not be present. This last refusal convinced the citizens of Cleveland that the manufacturers are in the wrong and their sympathy was on the side of the strikers.

In the meantime the manufacturers were trying with all their power to get their employees back to work. They visited the strikers in their homes, sent special delivery letters and even called them to a meeting in the factory, to a “meeting,” mind you! That morning every one of us were down at the factory where the “meeting” was to be held, and, strange as it may seem, not one answered the call! Not one.

Next they tried to open factories in the little towns near Cleveland, thinking that there they would get the people to do their work, but they forgot that we were on the lookout. I remember that when I came to speak at a meeting in Lorain, where a shop had been opened, after explaining the situation, one of the audience assured me that the shop would be closed down in a week or two. And thus it was. Similar stunts were done in the rest of the places. So this scheme of theirs did not work.

The importing of scabs seemed to be a very expensive proceeding. Even the few whom they succeeded in getting down here did not amount to much in so far as taking the places of the strikers was concerned. They were such as could not make cloaks. The strikers knew it. And, instead of being scared by the scab labor, they laughed at it.

Next they tried to accuse the strikers of being incendiaries and murderers. The old story! This, Mr. Employer, only shows that you are in a desperate position. that sooner or later you will have to give in to the demands of those who created your riches and wealth, or get out of business!

Peanuts and Pickets

A strike, like everything else, has its humorous side. It is not, however, cheap, or coarse humor. On the contrary, such humor is an inspiration to everyone who works for the day when human slavery will be a thing of the past.

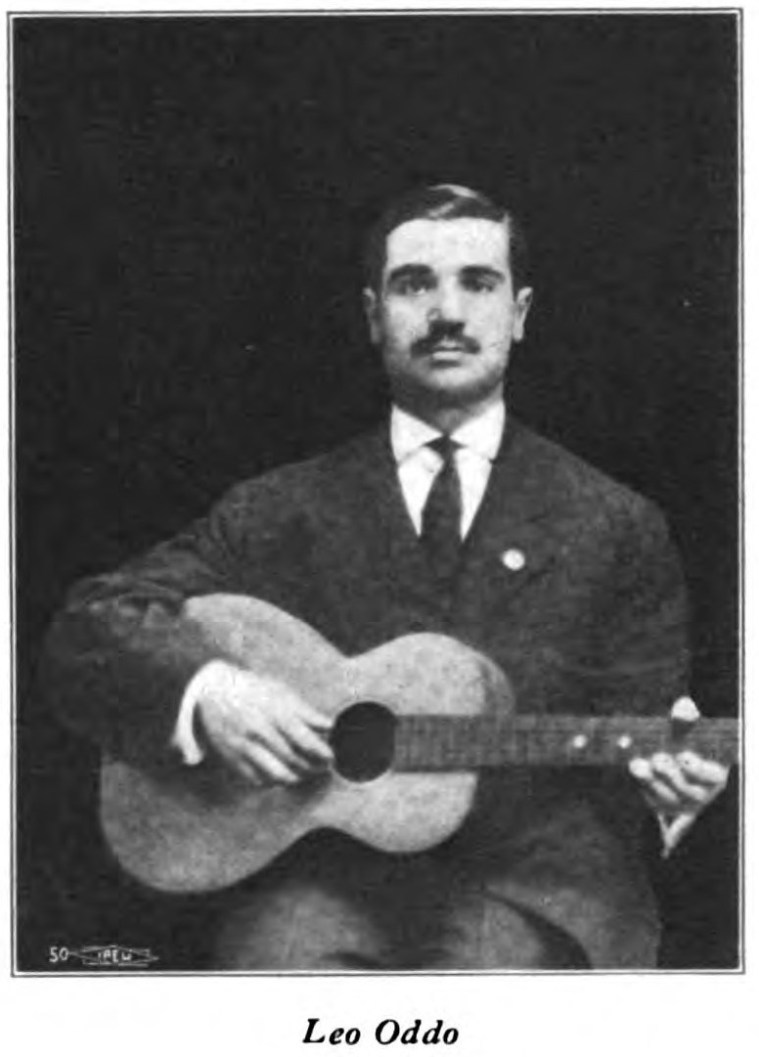

Look at the picture of Leo Oddo, and it is hard for you to imagine him dressed as a boy, is it not? Yet it was this Leo who shaved off his moustache, dressed himself in a blouse and knee pants, and barefooted, with a basket of peanuts and shoe laces, went into the factory where he had worked before, and where a few of the workers remained scabbing; went from machine to machine and spoke to the scabs, asking them to come down, and not until he was near the last scab, did the employer recognize him! He could not imagine the big Leo as a boy, and only when informed by one of the scabs, did he tell him to go.

Can you think of a more clever way to do your picketing?

Scabs Serenaded

The same Leo got together a bunch of Italians, with their mandolins, and went to the factory where some of the Italians were sleeping, stopped near the window, and began to sing and play. The song paraphrased words that were familiar to the Italians, as for instance: “Five hundred years ago the king of Italy imprisoned many people because they said something he did not like. Today the modern king imprisons us because we say ‘Scab, come down!’ Let us fight for better conditions together! Our arms are big enough to hold you, too!” Well! the officers ran over, and shouted, “What in h-ll are you singing about?” And Leo answered, “O, just a love song, we serenade Mr. Scab!” And what do you suppose? Ten of those who heard them sing came the next day and joined the Union.

***

Police Station Turned Into Meeting Hall

One day the police got busy and arrested about forty girls. When brought into the station, one of them said, “Listen, girls, let us have a meeting,” and this, of course, met with the approval of the others, so they elected a chairman, and Florence Shalor, whose picture you have before you, said, “Madam Chairman, what are we going to do about the police?” The girls were all discharged.

Next day they went picketing again, and the police, at least one of them, said to Florence that if she picketed again she would be arrested. And Florence simply lifted her big black eyes and asked, “Will you come to see me every day?” He, of course, could not see the humor of it and answered “No!” So Florence said very determinedly, “Then I don’t care to be arrested!”

While in jail they very often composed songs. Riding in the patrol wagons, they sang at the top of their voices. Here is one:

“Rah! Rah! Rah!

who are we?

who are we?

We are strikers,

can’t you see?”

This song was composed by a seventeen-year-old striker, pretty little Rose Levinson. But here is one more:

“All we ask is bail,

All that we get is jail,

All that we want is to fight

Until we get what is right.”

I could, indeed, go on and tell to the readers of Life and Labor many more stories, stories that fill the heart with joy, courage, and renews the energy to keep up this glorious fight. But I know that the space is limited. So I will conclude.

***

To my mind a strike is never lost. And this strike, in particular, cannot be lost. For this strike has done something for the striking garment workers that is worth more than money can buy. It has made them think. It has developed that glorious fighting spirit within them. It has brought out all that is best in them. It has done away with selfishness, race hatred, foolish pride, and that well known idea of “Each for himself, and the devil take the hindmost,” and has instead developed their minds to the beauty of “Each for all, and all for each.” This is what this strike has already accomplished. If only one strike can do that, then I ask can a strike ever be lost?

The Young Leaders

Look at the pictures! Look at Florence Shalor. An Italian, the first time on strike. Had a better position than the average girl of that trade, was liked by the employers, and got a pretty good wage, and yet how she responded to the call of her brothers and sisters! Has to support a family, but does not care, is determined to stay out just as long as it will be necessary. Acts as secretary for the Italians. Is doing picketing besides. In short, she is in that strike with her heart and soul! But, as Ben Hanford used to say, “Once a striker, always a striker!” I rejoice in thinking that we have gained one more who will at all times be ready to fight the battles of her class!

As you look at Ida Baxt, you can at once tell that she is an old soldier of Labor’s army. As president of her local

Union, she gives her time, her energy, the best that is in her, to the Labor Movement–has been a member of her Union for several years.

Look at Rose Becker! She surprised not only her employer by going down on strike, but also her own people of the shop. She was the favorite of the employer, was given good wages and good conditions and her shop mates wondered whether she would come down with them. But Rose came down, telling the employer that she was fighting not so much for herself as for those whose conditions were so much worse than hers!

And here is Rebecca Saul. You can see her at the strike headquarters from 5 a.m. until 10 or 11 p.m. Is constantly sending out the pickets, arranging matters, etc., is alive to subjects pertaining to the Labor Movement, intelligent and devoted to the Cause of Labor.

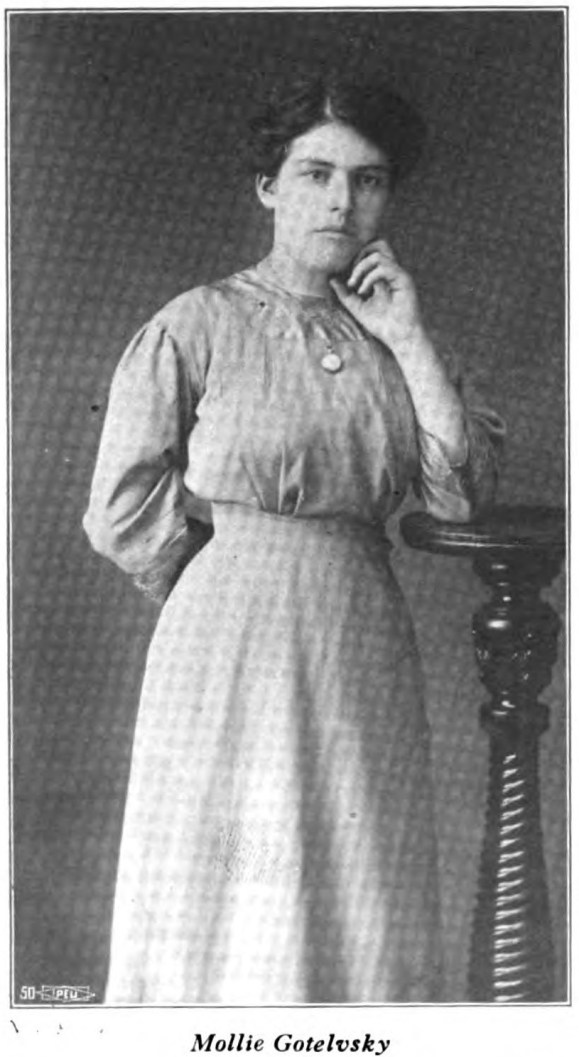

Mollie Gotelevsky is a personality whom you can’t forget. Mollie does not say much. Mollie thinks and acts. Mollie is one of those who does not look at the Trade Union Movement as the end, but as a means to an end! Mollie is an idealist, is yearning for a future where there will be no master and no slave, but all will enjoy the beauties of life! Admire Mollie because she is not only dreaming of a glorious future, as so many of her people do, but is giving her life to the movement that will some day bring about a realization of Mollie’s dream. They are dreams that Nations dream, and “dreams that Nations dream, must come true!”

For six weeks I have been with the strikers every moment during the day. It was hard work–but inspiring work. There I could see the working people, men and women, sacrificing everything for the Cause of Justice! Never shall I forget the heroism of the women.

A Striker’s Wife

A wife of a striker who went to convert another woman whose husband had been scabbing, was shot by a guard near the house. When her companion, also the wife of a striker, went to lift her up, the guard said that if she dared to go near the wounded he would shoot her, too. She looked at him, then at the woman lying on the ground in blood, and answered, “You can shoot me if you want, but I must pick up the woman!” And she was shot, in her leg. A woman who had never been in any fight before, a mother of children, risked her very life to help another! In what other movement can you find these types? In what other movement can you see such sacrifices? In what other movement can you find men and women who will lay down their lives in order to bring into being a system based on Truth and equal opportunity for all?

In no other but the Labor Movement.

Life and Labor was the monthly journal of the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). The WTUL was founded by the American Federation of Labor, which it had a contentious relationship with, in 1903. Founded to encourage women to join the A.F. of L. and for the A.F. of L. to take organizing women seriously, along with labor and workplace issues, the WTUL was also instrumental in creating whatever alliance existed between the labor and suffrage movements. Begun near the peak of the WTUL’s influence in 1911, Life and Labor’s first editor was Alice Henry (1857-1943), an Australian-born feminist, journalist, and labor activists who emigrated to the United States in 1906 and became office secretary of the Women’s Trade Union League in Chicago. She later served as the WTUL’s field organizer and director of the education. Henry’s editorship was followed by Stella M. Franklin in 1915, Amy W. Fields in in 1916, and Margaret D. Robins until the closing of the journal in 1921. While never abandoning its early strike support and union organizing, the WTUL increasingly focused on regulation of workplaces and reform of labor law. The League’s close relationship with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America makes ‘Life and Labor’ the essential publication for students of that union, as well as for those interest in labor legislation, garment workers, suffrage, early 20th century immigrant workers, women workers, and many more topics covered and advocated by ‘Life and Labor.’

PDF of issue: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b3859487?urlappend=%3Bseq=305%3Bownerid=9007199256678780-313